Volume 3, Issue 2 December 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Process of Brexit: What Comes Next?

LONDON’S GLOBAL UNIVERSITY THE PROCESS OF BREXIT: WHAT COMES NEXT? Alan Renwick Co-published with: Working Paper January 2017 All views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the UCL European Institute. © Alan Renwick (Image credit: Way out by Matt Brown; CC BY 2.0) The Process of Brexit: What Comes Next? Alan Renwick* * Dr Alan Renwick is Deputy Director of the UCL Constitution Unit. THE PROCESS OF BREXIT: WHAT COMES NEXT? DR ALAN RENWICK Executive Summary The phoney war around Brexit is almost over. The Supreme Court has ruled on Article 50. The government has responded with a bill, to which the House of Commons has given outline approval. The government has set out its negotiating objectives in a White Paper. By the end of March, if the government gets its way, we will be entering a new phase in the Brexit process. The question is: What comes next? What will the process of negotiating and agreeing Brexit terms involve? Can the government deliver on its objectives? What role might parliament play? Will the courts intervene again? Can the devolved administrations exert leverage? Is a second referendum at all likely? How will the EU approach the negotiations? This paper – so far as is possible – answers these questions. It begins with an overview of the Brexit process and then examines the roles that each of the key actors will play. The text was finalised on 2 February, shortly after publication of the government’s White Paper. Overview: Withdrawing from the EU Article 50 of the EU treaty sets out a four-step withdrawal process: the decision to withdraw; notification of that decision to the EU; negotiation of a deal; and agreement to the deal’s terms. -

Masaryk University Faculty of Education Department Of

Masaryk University Faculty of Education Department of English Language and Literature The Passive in the British Political News Bachelor thesis Brno 2017 Supervisor: Written by: Mgr. Renata Jančaříková, Ph.D. Karolína Šafářová Announcement I hereby declare that I have worked on this thesis independently and that I have used only the sources from the works cited list. Brno, 30 March 2017 ..…..………………… Karolína Šafářová Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Renata Jančaříková, Ph.D, for her guidance, kind support and valuable advice. Anotace Tato bakalářská práce The Passive in the British political news je zaměřena na užití trpného rodu v politických článcích na téma Brexit vyskytujících se v seriozních novinách The Guardian a bulváru The Daily Mail. V práci je použita kvantitatvní analýza za účelem srovnání výskytu činného a trpného rodu, vyhodnocení důvodů pro používání trpného rodu, analyzování výskytu významových a uvozovacích sloves, a poměru činitelů trpného rodu vyjádřených pomocí 'by'. Annotation This bachelor thesis The Passive in the British political news is focused on the use of the passive in the broadsheet The Guardian and the tabloid The Daily Mail on the topic of concerning Brexit. It uses quantitative analysis to compare the frequency of use of the active and the passive voice, to analyze reasons for using the passive, the frequency of occurrence of lexical and report verbs, and the proportion of agents expressed by 'by'. Klíčová slova trpný rod, činný rod, noviny, politické zprávy, The Guardian, The Daily Mail, analýza, kvalitní noviny, bulvár Key Words passive voice, active voice, newspaper, political news, The Guardian, The Daily Mail, analysis broadsheets, tabloids Content 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... -

Download the Guide

A Guide to Brexit Terminology This glossary has been designed to explain some of the key terms used in relation to Brexit. At the end of the glossary are links to additional resources and originals of key documents. The Glossary is not designed to be an exhaustive list and the authors hope that you find the explanations of key terms helpful. The UK which voted to join the EU had a different constitution to the UK that voted to leave the EU. This is reflected by some of the terminology used in the glossary and the inclusion of reference to the legislatures in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N |O| P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | A to Z of Brexit terms February 01 2019 version pg. 1 Advisory The Brexit referendum is often described as ‘only advisory’. The referendum was authorised and conducted under the European Union Referendum Act 2015. It is advisory because Parliament is sovereign and because the Act contained no enabling legislation. Enabling provisions are ones which explicitly state that Parliament is legally bound to implement the outcome of the referendum. Hence, Parliament was not legally obliged to enact the outcome of the Brexit referendum. In contrast, for countries with codified constitutions, the outcome of a referendum ‘may’, in some instances bind both parliament and the government to implement its result. In Britain, however, with an uncodified constitution, it is possible for the government to promise in advance that it would respect the result, but that promise would be only political and not legally binding as parliament cannot be bound be a previous parliament; it can change its mind. -

North Says NO to the Accord Educomp President Ron Taylor TERRACE ~ a Majority of Ing Firm

North says NO to the accord Educomp president Ron Taylor TERRACE ~ A majority of ing firm. vote 'yes', 56 per cent said it will vote 'no', 23 per cent said the said he has never seen such a northern B.C. residents will vote It sampled 658 voters between put an end to debate on the con- Charlottetown Accord will give Inside high ~ 40 per cent ~ won't vote 'no' to the proposed constitu- the Queen Charlotte Islands, east stitution. too much to Quebec. * On Page A2 you'll Another 21 per cent said their or won't answer response in his tional changes, indicates a poll to Prince George along Hwyl6 Another 23 per cent said it find more information years of polling. done for The Terrace Standard. and south to 100 Mile House. would be positive for the country vote was anti-government or anti- He said he thought hefivy 'yes' about what's happening The poll, conducted between The sample size gives a maxi- while 17 gave either no response Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. advertising would have had more h,cally with the constitu- Oct. 2 and OcL 9, found that 60 mum error of approximately plus or listed another reason. The aboriginal issue was listed of an impact on voters by now. per cent of those who said they or minus four per cent 19 times Only four per cent of 'yes' by 12 per cent of those who said tional referendum. And he pointed to the 21 per will vote, stated they will vote out of 20. -

'Good Gigs: a Fairer Future for the UK's Gig Economy'

Good Gigs A fairer future for the UK’s gig economy Brhmie Balaram, Josie Warden and Fabian Wallace-Stephens April 2017 Contents About us 3 Acknowledgments 4 Summary 5 1. The nature of Britain’s gig economy 10 Part I: The current trend 12 Part II: Insight into different experiences 23 Part III: Future prospects 30 2. Gig work as ‘good work’ 34 Part I: Understanding and defining employment relationships in the gig economy 35 Part II: Understanding the interactions between employment law, tax and welfare 39 Part III: Getting beyond the system with ‘good work’ 47 3. The potential of peer-to-peer platforms 49 4. Transforming the labour market together 56 Rethinking regulatory approaches 57 The RSA’s recommendations 58 Concluding remarks 64 2 Good Gigs: A fairer future for the UK’s gig economy About us Brhmie Balaram is a Senior Researcher at the RSA. Josie Warden is a Researcher at the RSA. Fabian Wallace-Stephens is a Data Research Assistant at the RSA. All work in the Economy, Enterprise and Manufacturing Team. The RSA (Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce) believes that everyone should have the freedom and power to turn their ideas into reality – we call this the Power to Create. Through our ideas, research and 28,000- strong Fellowship, we seek to realise a society where creative power is distributed, where concentrations of power are confronted, and where creative values are nurtured. The RSA Action and Research Centre combines practical experimentation with rigorous research to achieve these goals. MANGOPAY is an online payment technology designed for marketplaces, crowd- funding platforms and sharing economy businesses. -

Brexit Bulletin—UK and EU Announce a New Brexit Deal

Brexit Bulletin—UK and EU announce a new Brexit deal LNB News 17/10/2019 39 On 17 October 2019, the European Commission and UK government announced an agreement in principle on the revised legal terms of the Withdrawal Agreement, which includes a revised Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland and revised political declaration on the framework of the future EU-UK relationship. With the European Council ongoing, the Commission recommended that the European Council (Article 50) endorses the revised agreement and the European Parliament give its consent, but the deal cannot be ratified without the approval of the UK Parliament. Adam Cygan, professor in EU law at University of Leicester, Kieran Laird, partner at Gowling WLG and Laura Rees-Evans, senior associate at Fietta Law, comment on the agreement and provide insight into what happens next. What has been announced? As noted above, the UK and EU have announced agreement at negotiator level on a revised Withdrawal Agreement Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland and a revised Political Declaration on the framework of the future EU-UK relationship. In accordance with the European Commission’s original mandate, there are no substantive changes to the core text of the Withdrawal Agreement which was endorsed by the EU in 2018. Documents published set out the revised legal text of the Northern Ireland Protocol and political declaration, plus limited technical amendments to the previous Withdrawal Agreement. There are no substantive changes to the core text of the Withdrawal Agreement endorsed by the EU in 2018. With the European Council ongoing, the Commission recommended that the European Council (Article 50) endorses the revised agreement and the European Parliament give its consent, but the deal cannot be ratified without the approval of the UK Parliament. -

Hong Kong Leader Seeks an End to Violence, Promises Dialogue

EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE DELHI THE HINDU 14 WORLD THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2019 EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE ELSEWHERE Hong Kong leader seeks an end British lawmakers vote on to violence, promises dialogue Bill to block no-deal Brexit PM Boris Johnson demands snap election on October 15 Govt. is withdrawing extradition Bill to fully allay public concerns, says Carrie Lam ‘UN rights chief meddling Reuters in Brazil’s internal affairs’ Reuters LONDON HONG KONG BRASŢLIA The British Parliament on Brazil President Jair Hong Kong leader Carrie Wednesday voted to prevent Bolsonaro on Wednesday accused United Nations Lam, who on Wednesday Prime Minister Boris John human rights chief Michelle withdrew the controversial son taking Britain out of the Bachelet of meddling in his extradition Bill, expressed European Union without a country’s affairs after she hope -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography by the late F. Seymour-Smith Reference books and other standard sources of literary information; with a selection of national historical and critical surveys, excluding monographs on individual authors (other than series) and anthologies. Imprint: the place of publication other than London is stated, followed by the date of the last edition traced up to 1984. OUP- Oxford University Press, and includes depart mental Oxford imprints such as Clarendon Press and the London OUP. But Oxford books originating outside Britain, e.g. Australia, New York, are so indicated. CUP - Cambridge University Press. General and European (An enlarged and updated edition of Lexicon tkr WeltliU!-atur im 20 ]ahrhuntkrt. Infra.), rev. 1981. Baker, Ernest A: A Guilk to the B6st Fiction. Ford, Ford Madox: The March of LiU!-ature. Routledge, 1932, rev. 1940. Allen and Unwin, 1939. Beer, Johannes: Dn Romanfohrn. 14 vols. Frauwallner, E. and others (eds): Die Welt Stuttgart, Anton Hiersemann, 1950-69. LiU!-alur. 3 vols. Vienna, 1951-4. Supplement Benet, William Rose: The R6athr's Encyc/opludia. (A· F), 1968. Harrap, 1955. Freedman, Ralph: The Lyrical Novel: studies in Bompiani, Valentino: Di.cionario letU!-ario Hnmann Hesse, Andrl Gilk and Virginia Woolf Bompiani dille opn-e 6 tUi personaggi di tutti i Princeton; OUP, 1963. tnnpi 6 di tutu le let16ratur6. 9 vols (including Grigson, Geoffrey (ed.): The Concise Encyclopadia index vol.). Milan, Bompiani, 1947-50. Ap of Motkm World LiU!-ature. Hutchinson, 1970. pendic6. 2 vols. 1964-6. Hargreaves-Mawdsley, W .N .: Everyman's Dic Chambn's Biographical Dictionary. Chambers, tionary of European WriU!-s. -

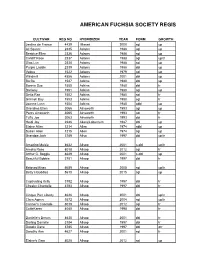

Regn Lst 1948 to 2020.Xls

AMERICAN FUCHSIA SOCIETY REGISTERED FUCHSIAS, 1948 - 2020 CULTIVAR REG NO HYBRIDIZER YEAR FORM GROWTH Jardins de France 4439 Massé 2000 sgl up All Square 2335 Adams 1988 sgl up Beatrice Ellen 2336 Adams 1988 sgl up Cardiff Rose 2337 Adams 1988 sgl up/tr Glas Lyn 2338 Adams 1988 sgl up Purple Laddie 2339 Adams 1988 dbl up Velma 1522 Adams 1979 sgl up Windmill 4556 Adams 2001 dbl up Bo Bo 1587 Adkins 1980 dbl up Bonnie Sue 1550 Adkins 1980 dbl tr Dariway 1551 Adkins 1980 sgl up Delta Rae 1552 Adkins 1980 sgl tr Grinnell Bay 1553 Adkins 1980 sgl tr Joanne Lynn 1554 Adkins 1980 sdbl up Grandma Ellen 3066 Ainsworth 1993 sgl up Percy Ainsworth 3065 Ainsworth 1993 sgl tr Tufty Joe 3063 Ainsworth 1993 dbl tr Heidi Joy 2246 Akers/Laburnum 1987 dbl up Elaine Allen 1214 Allen 1974 sdbl up Susan Allen 1215 Allen 1974 sgl up Grandpa Jack 3789 Allso 1997 dbl up/tr Amazing Maisie 4632 Allsop 2001 s-dbl up/tr Amelia Rose 8018 Allsop 2012 sgl tr Arthur C. Boggis 4629 Allsop 2001 s-dbl up Beautiful Bobbie 3781 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Beloved Brian 5689 Allsop 2005 sgl up/tr Betty’s Buddies 8610 Allsop 2015 sgl up Captivating Kelly 3782 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Cheeky Chantelle 3783 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Cinque Port Liberty 4626 Allsop 2001 dbl up/tr Clara Agnes 5572 Allsop 2004 sgl up/tr Conner's Cascade 8019 Allsop 2012 sgl tr CutieKaren 4040 Allsop 1998 dbl tr Danielle’s Dream 4630 Allsop 2001 dbl tr Darling Danielle 3784 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Doodie Dane 3785 Allsop 1997 dbl gtr Dorothy Ann 4627 Allsop 2001 sgl tr Elaine's Gem 8020 Allsop 2012 sgl up Generous Jean 4813 -

UK's Withdrawal from the European Union

Library Briefing UK’s Withdrawal from the European Union Debate on 19 October 2019 The House of Lords will sit on Saturday 19 October 2019. This will be the first weekend sitting since 1982. The following motions have been tabled under the name of Lord Callanan, Minister of State at the Department for Exiting the European Union: that for the purposes of section 1(1)(b) of the European Union (Withdrawal) (No. 2) Act 2019 and section 13(1)(c) of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, this House takes note of the negotiated withdrawal agreement titled “Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community” and the framework for the future relationship titled “Political Declaration setting out the framework for the future relationship between the European Union and the United Kingdom” that the United Kingdom has concluded with the European Union under Article 50(2) of the Treaty on European Union, as well as a “Declaration by Her Majesty’s Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning the operation of the ‘Democratic consent in Northern Ireland’ provision of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland”, copies of which three documents were laid before the House on Saturday 19 October. that for the purposes of section 1(2)(b) of the European Union (Withdrawal) (No. 2) Act 2019, this House takes note of the statement laid before the House on Saturday 19 October titled “Statement that the United Kingdom is to leave the European Union without an agreement having been reached under Article 50(2) of the Treaty on European Union”. -

Complete V.12 No.2

Journal of Civil Law Studies Volume 12 Number 2 2019 Article 15 12-31-2019 Complete V.12 No.2 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/jcls Part of the Civil Law Commons Repository Citation Complete V.12 No.2, 12 J. Civ. L. Stud. (2019) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/jcls/vol12/iss2/15 This Complete Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Law Studies by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 12 Number 2 2019 ___________________________________________________________________________ ARTICLES . Changes in the Legal System: A Comparative Essay Based on the Hungarian Experience Attila Harmathy . A Cacophony of Speech, Law, and Persona: Battling Against the Vortex of #MeToo in France and the U.S. Anne Wagner & Sarah Marusek NOTE . The Digest Online Project: A Resource to Disseminate the Legal Heritage of Louisiana Agustín Parise CIVIL LAW IN THE WORLD . Scotland Brexit, Boris Johnson and the Nobile Officium Stephen Thomson BOOK REVIEWS . Yaëll Emerich, Conceptualising Property Law: Integrating Common Law and Civil Law Traditions John A. Lovett . James R. Maxeiner, Failures of American Methods of Lawmaking in Historical and Comparative Perspectives Scott J. Burnham Markus G. Puder . Tamar Herzog, A Short History of European Law: The Last Two and a Half Millennia Agustín Parise Also in this issue: CIVIL LAW IN LOUISIANA JOURNAL OF CIVIL LAW STUDIES Editor-in-Chief Olivier Moréteau Louisiana State University Paul M. -

Rhyming Dictionary

Merriam-Webster's Rhyming Dictionary Merriam-Webster, Incorporated Springfield, Massachusetts A GENUINE MERRIAM-WEBSTER The name Webster alone is no guarantee of excellence. It is used by a number of publishers and may serve mainly to mislead an unwary buyer. Merriam-Webster™ is the name you should look for when you consider the purchase of dictionaries or other fine reference books. It carries the reputation of a company that has been publishing since 1831 and is your assurance of quality and authority. Copyright © 2002 by Merriam-Webster, Incorporated Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Merriam-Webster's rhyming dictionary, p. cm. ISBN 0-87779-632-7 1. English language-Rhyme-Dictionaries. I. Title: Rhyming dictionary. II. Merriam-Webster, Inc. PE1519 .M47 2002 423'.l-dc21 2001052192 All rights reserved. No part of this book covered by the copyrights hereon may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems—without written permission of the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America 234RRD/H05040302 Explanatory Notes MERRIAM-WEBSTER's RHYMING DICTIONARY is a listing of words grouped according to the way they rhyme. The words are drawn from Merriam- Webster's Collegiate Dictionary. Though many uncommon words can be found here, many highly technical or obscure words have been omitted, as have words whose only meanings are vulgar or offensive. Rhyming sound Words in this book are gathered into entries on the basis of their rhyming sound. The rhyming sound is the last part of the word, from the vowel sound in the last stressed syllable to the end of the word.