Transesophageal Echocardiography in Evaluation and Management After a Fontan Procedure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Diastolic Clicks After the Fontan Procedure for Double

304 Br Heart J 1990;63:304-7 Early diastolic clicks after the Fontan procedure for double inlet left ventricle: anatomical and physiological correlates Br Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.63.5.304 on 1 May 1990. Downloaded from Andrew N Redlngton, Kit-Yee Chan, Julene S Carvalho, Elliot A Shinebourne Abstract inlet ventricle with two atrioventricular M mode echocardiograms and simultan- valves. All had previously undergone a Fontan eous phonocardiograms were recorded type procedure with direct atriopulmonary in four patients with early diastolic anastomosis. In two patients a valved clicks on auscultation. All had double homograft was interposed between the right inlet left ventricle and had undergone atrium and pulmonary artery. Each patient the Fontan procedure with closure of the had the right atrioventricular valve closed by right atrioventricular valve orifice by an either a single or double layer of Dacron cloth artifical patch. The phonocardiogram sewn into the floor of the right atrium. The confirmed a high frequency sound main pulmonary artery was tied off in all. occurring 60-90 ms after aortic valve Cross sectional, M mode, and pulsed wave closure and coinciding with the time of Doppler echocardiograms with simultaneous maximal excursion of the atrioven- electrocardiogram and phonocardiogram were tricular valve patch towards the ven- recorded on a Hewlett-Packard 77020A tricular mass. One patient had coexist- ultrasound system. The phonocardiogram was ing congenital complete heart block. recorded over the point on the chest where the The M mode echocardiogram showed diastolic click was best heart on auscultation, i'reversed") motion of the patch towards usually in the fourth left intercostal space the right atrium during atrial contrac- close to the sternum. -

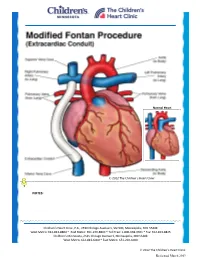

Modified Fontan Procedure: Extracardiac Conduit

Normal Heart © 2012 The Children’s Heart Clinic NOTES: Children’s Heart Clinic, P.A., 2530 Chicago Avenue S, Ste 500, Minneapolis, MN 55404 West Metro: 612-813-8800 * East Metro: 651-220-8800 * Toll Free: 1-800-938-0301 * Fax: 612-813-8825 Children’s Minnesota, 2525 Chicago Avenue S, Minneapolis, MN 55404 West Metro: 612-813-6000 * East Metro: 651-220-6000 © 2012 The Children’s Heart Clinic Reviewed March 2019 Modified Fontan Procedure: Extracardiac Conduit The Fontan procedure is usually the third procedure done in a series of surgeries to complete palliation of single ventricle patients. This procedure separates the “blue,” deoxygenated blood from the “red,” oxygenated blood circuit. Once the Fontan is done, deoxygenated blood drains passively to the pulmonary arteries, then to the lungs. Blood receives oxygen from the lungs and returns to the heart, where it is actively pumped out to the body. This procedure is usually done between 2-4 years of age. During surgery, the chest is opened through the previous incision, using a median sternotomy. The operation may or may not involve the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (heart-lung machine), depending on the surgical plan. A Gore-tex® tube graft (Gore) is cut to the appropriate length. An incision is made on the pulmonary artery near the area of the existing bidirectional Glenn shunt (cavopulmonary anastomosis) and the tube graft is sutured to the artery. Once that is complete, the inferior vena cava is divided from the atrium. The lower end of the Gore-tex® tube graft (Gore) is then sutured to the inferior vena cava. -

The Physiology of the Fontan Circulation ⁎ Andrew Redington

Progress in Pediatric Cardiology 22 (2006) 179–186 www.elsevier.com/locate/ppedcard The physiology of the Fontan circulation ⁎ Andrew Redington Division of Cardiology, The Department of Pediatrics, The Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto School of Medicine, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Available online 8 September 2006 Abstract The Fontan circulation, no matter which of its various iterations, is abnormal in virtually every aspect of its performance. Some of these abnormalities are primarily the result of the procedure itself, and others are secondary to the fundamental disturbances of circulatory performance imposed by the ‘single’ ventricle circulation. The physiology of ventricular, systemic arterial and venopulmonary function will be described in this review. © 2006 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: palliation; Fontan circulation; Cavopulmonary anastomosis; Antriopulmonary anastomosis 1. Introduction has the profound consequences for the systemic ventricle that will discussed below. At the same time as the bidirectional In this personal overview, I will discuss the physiology of the cavopulmonary anastomosis was becoming almost uniformly Fontan circulation. Bob Freedom's contribution to our under- adopted, there was abandonment of the ‘classical’ atriopulmon- standing of complex congenital heart disease has meant that ary anastomosis, in favour of the total cavopulmonary con- many more of these patients are surviving with this physiology nection (TCPC). The ‘lateral wall’ TCPC, popularised by Marc than could have been contemplated 30 years ago. Nonetheless, deLeval [1], was shown experimentally and clinically to be they represent a very difficult group of patients and we continue haemodynamically more efficient [1,2] and set the scene for the to learn more about this unique circulation. -

Arterial Switch Operation Surgery Surgical Solutions to Complex Problems

Pediatric Cardiovascular Arterial Switch Operation Surgery Surgical Solutions to Complex Problems Tom R. Karl, MS, MD The arterial switch operation is appropriate treatment for most forms of transposition of Andrew Cochrane, FRACS the great arteries. In this review we analyze indications, techniques, and outcome for Christian P.R. Brizard, MD various subsets of patients with transposition of the great arteries, including those with an intact septum beyond 21 days of age, intramural coronary arteries, aortic arch ob- struction, the Taussig-Bing anomaly, discordant (corrected) transposition, transposition of the great arteries with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, and univentricular hearts with transposition of the great arteries and subaortic stenosis. (Tex Heart Inst J 1997;24:322-33) T ransposition of the great arteries (TGA) is a prototypical lesion for pediat- ric cardiac surgeons, a lethal malformation that can often be converted (with a single operation) to a nearly normal heart. The arterial switch operation (ASO) has evolved to become the treatment of choice for most forms of TGA, and success with this operation has become a standard by which pediatric cardiac surgical units are judged. This is appropriate, because without expertise in neonatal anesthetic management, perfusion, intensive care, cardiology, and surgery, consistently good results are impossible to achieve. Surgical Anatomy of TGA In the broad sense, the term "TGA" describes any heart with a discordant ven- triculoatrial (VA) connection (aorta from right ventricle, pulmonary artery from left ventricle). The anatomic diagnosis is further defined by the intracardiac fea- tures. Most frequently, TGA is used to describe the solitus/concordant/discordant heart. -

Norwood/Batista Operation for a Newborn with Dilated Myopathy of the Left Ventricle

612 Brief communications The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery September 2000 NORWOOD/BATISTA OPERATION FOR A NEWBORN WITH DILATED MYOPATHY OF THE LEFT VENTRICLE Richard D. Mainwaring, MD, Regina M. Healy, BS, John D. Murphy, MD, and William I. Norwood, MD, PhD, Wilmington, Del Partial left ventriculectomy for dilated cardiomyopathy was contractile function. The variable results that have been first reported by Batista and associates1 in 1996. The rationale reported in the adult literature may reflect patient selection for this procedure is the increase in left ventricular cavity size according to the reversibility or recoverability of the underly- in the absence of compensatory left ventricular wall thickness ing disease process. that is observed in dilated cardiomyopathy. This combination Despite the substantial worldwide experience with the of factors results in an increase in wall stress per unit muscle Batista procedure in adult patients, there is limited experience mass, as predicted by the LaPlace equation. As wall stress with this procedure in children. The current case report increases, mechanical load eventually becomes nonsustain- describes the treatment of a patient in whom the diagnosis of able and contributes to further dilation of the ventricle. Partial dilated cardiomyopathy was made in utero. left ventriculectomy has been advocated as a method of Clinical summary. A female infant was recognized in restoring the balance between cavity size and wall thickness. utero as having a dilated, poorly functioning left ventricle. Fundamental to this concept is the assumption that the left Labor was induced at 36 weeks’ gestation, and she was deliv- ventricular muscle is intrinsically normal or has recoverable ered by normal, spontaneous, vaginal delivery. -

The Clinical Spectrum of Fontan-Associated Liver Disease: Results from a Prospective Multimodality Screening Cohort

Edinburgh Research Explorer The clinical spectrum of Fontan-associated liver disease: results from a prospective multimodality screening cohort Citation for published version: Munsterman, ID, Duijnhouwer, AL, Kendall, TJ, Bronkhorst, CM, Ronot, M, van Wettere, M, van Dijk, APJ, Drenth, JPH & Tjwa, ETTL 2019, 'The clinical spectrum of Fontan-associated liver disease: results from a prospective multimodality screening cohort', European Heart Journal, vol. 40, no. 13, pp. 1057–1068. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy620 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy620 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: European Heart Journal General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Title: The clinical spectrum of Fontan-Associated Liver Disease: results from a prospective multimodality screening cohort. Authors: I.D. Munsterman1, A.L. Duijnhouwer2, T.J. Kendall3, C.M. Bronkhorst4, M. Ronot5, M. van Wettere5, A.P.J. van Dijk2, J.P.H. Drenth1, E.T.T.L. Tjwa1 On behalf of the Nijmegen Fontan Initiative (A.P.J. -

ICD-10 Coordination and Maintenance Committee Agenda

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 7500 Security Boulevard Baltimore, Maryland 21244-1850 Agenda ICD-10 Coordination and Maintenance Committee Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CMS Auditorium 7500 Security Boulevard Baltimore, MD 21244-1850 ICD-10-PCS Topics March 7, 2017 Pat Brooks, CMS – Co -Chairperson Webcast and Dial-In Information The meeting will begin promptly at 9am ET and will be webcast. Toll-free dial-in access is available for participants who cannot join the webcast: Phone: 1-844-396-8222; Meeting ID: 909 233 082. We encourage you to join early, as the number of phone lines is limited. If participating via the webcast or dialing in you do NOT need to register on-line for the meeting. This meeting is being webcast via CMS at http://www.cms.gov/live/. By your attendance, you are giving consent to the use and distribution of your name, likeness and voice during the meeting. You are also giving consent to the use and distribution of any personally identifiable information that you or others may disclose about you during the meeting. Please do not disclose personal health information. Note: Proposals for diagnosis code topics are scheduled for March 8, 2017 and will be led by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Please visit CDCs website for the Diagnosis agenda located at the following address: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm_maintenance.htm 1 Introductions and Overview Pat Brooks ICD-10-PCS Topics: 1. Cerebral Embolic Protection During Michelle Joshua Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Alexandra Lansky, MD Pages 10-11 Professor of Medicine, Section of Cardiology Yale School of Medicine 2. -

Title of Thesis

Heart rate variability and pacemaker treatment in children with Fontan circulation Jenny Alenius Dahlqvist Department of Clinical Sciences, Pediatrics Department of Radiation Sciences Umeå 2019 This work is protected by the Swedish Copyright Legislation (Act 1960:729) Dissertation for PhD ISBN: 978-91-7855-007-4 ISSN: 0346-6612 New series no: 2022 Cover illustration: Sigge Mårtensgård Klüft, 6 years. Layout cover: Inhousebyrån, Umeå universitet. Electronic version available at: http://umu.diva-portal.org/ Printed by: UmU Print Service Umeå, Sweden 2019 1 To children with Fontan circulation Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................. 4 Background ............................................................................................................... 4 Aim ............................................................................................................................. 4 Methods ...................................................................................................................... 4 Results ........................................................................................................................ 4 Conclusions ................................................................................................................. 5 Abbreviations .................................................................................... 6 Original papers ................................................................................ -

Palliative Arterial Switch Operation As an Alternative for Selected Cases

PALLIATIVE ARTERIAL SWITCH OPERATION AS AN ALTERNATIVE FOR SELECTED CASES: SINGLE CENTERS‘ EXPERIENCE AND MID TERM RESULTS Okan Yurdak¨ok1, Murat ¸Ci¸cek1, Oktay Korun1, Firat Altin1, Mehmet Bi¸cer2, Yasemin Altuntas1, Emine Hekim Yilmaz1, Ahmet Sasmazel1, and Numan Aydemir1 1Dr Siyami Ersek Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery Training and Research Hospital 2Kartal Kosuyolu Training and Research Hospital June 10, 2020 Abstract ABSTRACT Introduction and Objective: There are various management options for newborns with single ventricle physiol- ogy, ventriculoarterial discordance and subaortic stenosis (SOS), classically involving the early pulmonary banding and aortic arch repair, the restricted bulboventriculer foramen(BVF) enlargement or the Norwood and the Damus Kaye Stansel (DKS) procedures. The aim of this study is to evaluate the midterm results of our clinical experience with palliative arterial switch operation (pASO) for this subset of patients. Method: We hereby retrospectively evaluate the charts of patients going through pASO, as initial palliation through Fontan pathway, starting from 2014 till today. Results: 10 patients underwent an initial palliative arterial switch procedure. 8 of 10 patients survived the operation and discharged. 7 of 10 patients completed stage II and 1 patient reached the Fontan completion stage and the other six of ten (6/10) patients are doing well and waiting for the next stage of palliation. There are two mortalities in the series (2/10) and one patient lost to follow-up (1/10). Conclusions: The pASO can be considered as an alternative palliation option for patients with single ventricle physiology, transposition of the great arteries and systemic outflow obstruction. It not only preserves systolic and diastolic ventricular function, but also provides a superior anatomic arrangement for following stages. -

A Quarterly Publication of the Central Office on ICD-9-CM Volume 31 First Quarter Number 1 2014

A quarterly publication of the Central Office on ICD-9-CM Volume 31 First Quarter Number 1 2014 In this issue Farewell Coding Clinic for ICD-9-CM 3 Ask the Editor Atypical Meningioma 16 Complicated Bereavement 10 Electrical Status Epilepticus of Sleep 11 Extracardiac Fontan Procedure 9 Fluctuations in Body Mass Index (BMI) 17 Heart Failure and Preserved or Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFpEF/HFrEF) 6 Heat Ablation of Saphenous Vein 6 Hemi-Fontan Procedure with Pulmonary Artery Augmenation 15 Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura and Pancytopenia 7 Infected Total Knee Replacement due to Corynebacterium Diphtheriae 5 LINX Reflux Management System 7 Malone Antegrade Continence Enema (MACE) Procedure 15 MOST Prosthetic Total Femoral Replacement 12 Multifocal Motor Neuropathy 10 Neuroendocrine Small Cell Carcinoma of the Cervix 5 Nonconvulsive Status Epilepticus 12 Previable Newborn 16 Progressive Familial Intrahepatic Cholestasis Type II 8 Renal Denervation 8 Retained Laparotomy Sponge during Cesarean Delivery 14 Splenosis 11 Traumatic Urinary Catheterization 12 Clarification Bacteremia Due to PICC Line 18 Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes and Preterm Delivery 19 Correction Dissection of Internal Carotid Artery 20 Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) Sepsis 20 Notice Update––Foreign Body Left During Surgery 21 Coding Clinic First Quarter 2014 1 Coding advice or code assignments contained in this issue effective with discharges March 31, 2014. Coding Clinic Gretchen Young-Charles, Robert Haralson, M.D. for ICD•10•CM/PCS RHIA, Senior Coding Representative for Consultant, Central Office American Medical Published quarterly by the on ICD-10-CM/PCS Association, Walland, TN American Hospital Association Halima Zayyad-Matarieh, Erika Hardy, RHIA, CCS, Central Office on ICD-10-CM/PCS RHIA, Coding Consultant, CDIP, Assistant Director of 155 N. -

Fontan Circulation and Arrhythmia

Fontan circulation and arrhythmia This information is designed for use by young people medical information on you at all times (eg. Medical with a Fontan circulation and their families. ID bracelet or use a health app on your phone). Why do you need to know about arrhythmia? What do you need to look out for? It is common for people who have a Fontan Watch for symptoms such as: circulation to develop problems with their heart rhythm, this is called an arrhythmia. Up to 40% of shortness of breath patients with Fontan circulation will develop at least feeling lightheaded one arrhythmia in the 10 years after having Fontan fainting surgery. Arrhythmias commonly occur because of palpitations (feeling a fast or irregular heart beat) dilation and scarring (from surgery) in the top chest pain chambers of the heart (the atria). If you notice any of these symptoms you should The chance of developing arrhythmias has reduced immediately seek medical attention. over time as the Fontan procedure has been refined It is possible to have an arrhythmia and not feel that and improved, so patients with an extracardiac anything is wrong. This is one of the reasons why Fontan (the most common type of Fontan operation regularly attending your follow up appointments is done since about 1990) have the lowest rate of important. arrhythmia compared to other, older types of Fontan circulation. Your cardiologist will regularly perform an ECG or Holter Monitor to check your heart rhythm. You Fast heart beats (tachyarrhythmias) are more may hear a normal heart rhythm be described as common than slow heart beats (bradyarrhythmias). -

December 2011 Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome in in THIS ISSUE the Neonate by Srilatha Alapati, MD and P

NEONATOLOGY TODAY News and Information for BC/BE Neonatologists and Perinatologists Volume 6 / Issue 12 December 2011 Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome in IN THIS ISSUE the Neonate By Srilatha Alapati, MD and P. Syamasundar other complex forms of congenital heart disease Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome in whom a two-ventricle repair is not possible. in the Neonate Rao, MD by Srilatha Alapati, MD and P. Syamasundar Rao, MD In this review, we will discuss anatomic, physiol- Page 1 Introduction ogic, and clinical features, noninvasive and inva- sive evaluation, management, and prognosis of A Brief History of Xenon and In the past, we discussed several general topics HLHS. Neuroprotection about Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) in the by Meredith Holmes, BA and Jerold F. neonate,1-5 but recently we began addressing Pathological Anatomy Lucey, MD, FAAP individual cardiac lesions such as transposition of Page 10 the great arteries6 and Tetralogy of Fallot.7 In this The left ventricle is usually a thick-walled, slit-like issue of Neonatology Today we will discuss Hy- cavity, especially when mitral atresia is present. DEPARTMENTS poplastic Left Heart Syndrome. Usually the aortic valve is severely stenosed or Medical Meeting Focus atretic and its annulus hypoplastic. Similarly, the Page 9 Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome mitral valve may be hypoplastic, severely stenotic or atretic. When the mitral valve is open, the left Medical News, Products and The term, Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome ventricular cavity is very small. Endocardial fi- Information (HLHS), initially proposed by Noonan and broelastosis is usually present. The ascending Page 11 Nadas,8 describes a diminutive left ventricle with aorta is hypoplastic; its diameter may be 2 to 3 underdevelopment of mitral and aortic valves.