ATOC 3050 Homework 11 Air Masses and Fronts Instructions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weather Charts Natural History Museum of Utah – Nature Unleashed Stefan Brems

Weather Charts Natural History Museum of Utah – Nature Unleashed Stefan Brems Across the world, many different charts of different formats are used by different governments. These charts can be anything from a simple prognostic chart, used to convey weather forecasts in a simple to read visual manner to the much more complex Wind and Temperature charts used by meteorologists and pilots to determine current and forecast weather conditions at high altitudes. When used properly these charts can be the key to accurately determining the weather conditions in the near future. This Write-Up will provide a brief introduction to several common types of charts. Prognostic Charts To the untrained eye, this chart looks like a strange piece of modern art that an angry mathematician scribbled numbers on. However, this chart is an extremely important resource when evaluating the movement of weather fronts and pressure areas. Fronts Depicted on the chart are weather front combined into four categories; Warm Fronts, Cold Fronts, Stationary Fronts and Occluded Fronts. Warm fronts are depicted by red line with red semi-circles covering one edge. The front movement is indicated by the direction the semi- circles are pointing. The front follows the Semi-Circles. Since the example above has the semi-circles on the top, the front would be indicated as moving up. Cold fronts are depicted as a blue line with blue triangles along one side. Like warm fronts, the direction in which the blue triangles are pointing dictates the direction of the cold front. Stationary fronts are frontal systems which have stalled and are no longer moving. -

NWS Unified Surface Analysis Manual

Unified Surface Analysis Manual Weather Prediction Center Ocean Prediction Center National Hurricane Center Honolulu Forecast Office November 21, 2013 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers…………….3 Chapter 2: Datasets available for creation of the Unified Analysis………...…..5 Chapter 3: The Unified Surface Analysis and related features.……….……….19 Chapter 4: Creation/Merging of the Unified Surface Analysis………….……..24 Chapter 5: Bibliography………………………………………………….…….30 Appendix A: Unified Graphics Legend showing Ocean Center symbols.….…33 2 Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers 1. INTRODUCTION Since 1942, surface analyses produced by several different offices within the U.S. Weather Bureau (USWB) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) National Weather Service (NWS) were generally based on the Norwegian Cyclone Model (Bjerknes 1919) over land, and in recent decades, the Shapiro-Keyser Model over the mid-latitudes of the ocean. The graphic below shows a typical evolution according to both models of cyclone development. Conceptual models of cyclone evolution showing lower-tropospheric (e.g., 850-hPa) geopotential height and fronts (top), and lower-tropospheric potential temperature (bottom). (a) Norwegian cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) and (III) narrowing warm sector, (IV) occlusion; (b) Shapiro–Keyser cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) frontal fracture, (III) frontal T-bone and bent-back front, (IV) frontal T-bone and warm seclusion. Panel (b) is adapted from Shapiro and Keyser (1990) , their FIG. 10.27 ) to enhance the zonal elongation of the cyclone and fronts and to reflect the continued existence of the frontal T-bone in stage IV. -

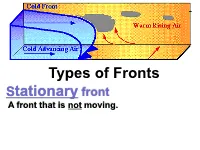

Types of Fronts Stationary Front a Front That Is Not Moving

Types of Fronts Stationary front A front that is not moving. Types of Fronts Cold front is a leading edge of colder air that is replacing warmer air. Types of Fronts Warm front is a leading edge of warmer air that is replacing cooler air. Types of Fronts Occluded front: When a cold front catches up to a warm front. Types of Fronts Dry Line Separates a moist air mass from a dry air mass. A.Cold Front is a transition zone from warm air to cold air. A cold front is defined as the transition zone where a cold air mass is replacing a warmer air mass. Cold fronts generally move from northwest to southeast. The air behind a cold front is noticeably colder and drier than the air ahead of it. When a cold front passes through, temperatures can drop more than 15 degrees within the first hour. The station east of the front reported a temperature of 55 degrees Fahrenheit while a short distance behind the front, the temperature decreased to 38 degrees. An abrupt temperature change over a short distance is a good indicator that a front is located somewhere in between. B. Warm Front. • A transition zone from cold air to warm air. • A warm front is defined as the transition zone where a warm air mass is replacing a cold air mass. Warm fronts generally move from southwest to northeast . The air behind a warm front is warmer and more moist than the air ahead of it. When a warm front passes through, the air becomes noticeably warmer and more humid than it was before. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Surface Station Model (U.S.)

Surface Station Model (U.S.) Notes: Pressure Leading 10 or 9 is not plotted for surface pressure Greater than 500 = 950 to 999 mb Less than 500 = 1000 to 1050 mb 988 Æ 998.8 mb 200 Æ 1020.0 mb Sky Cover, Weather Symbols on a Surface Station Model Wind Speed How to read: Half barb = 5 knots Full barb = 10 knots Flag = 50 knots 1 knot = 1 nautical mile per hour = 1.15 mph = 65 knots The direction of the Wind direction barb reflects which way the wind is coming from NORTHERLY From the north 360° 270° 90° 180° WESTERLY EASTERLY From the west From the east SOUTHERLY From the south Four types of fronts COLD FRONT: Cold air overtakes warm air. B to C WARM FRONT: Warm air overtakes cold air. C to D OCCLUDED FRONT: Cold air catches up to the warm front. C to Low pressure center STATIONARY FRONT: No movement of air masses. A to B Fronts and Extratropical Cyclones Feb. 24, 2007 Case In mid-latitudes, fronts are part of the structure of extratropical cyclones. Extratropical cyclones form because of the horizontal temperature gradient and are part of the general circulation—helping to transport energy from equator to pole. Type of weather and air masses in relation to fronts: Feb. 24, 2007 case mPmP cPcP mTmT Characteristics of a front 1. Sharp temperature changes over a short distance 2. Changes in moisture content 3. Wind shifts 4. A lowering of surface pressure, or pressure trough 5. Clouds and precipitation We’ll see how these characteristics manifest themselves for fronts in North America using the example from Feb. -

Chapter 4: Fog

CHAPTER 4: FOG Fog is a double threat to boaters. It not only reduces visibility but also distorts sound, making collisions with obstacles – including other boats – a serious hazard. 1. Introduction Fog is a low-lying cloud that forms at or near the surface of the Earth. It is made up of tiny water droplets or ice crystals suspended in the air and usually gets its moisture from a nearby body of water or the wet ground. Fog is distinguished from mist or haze only by its density. In marine forecasts, the term “fog” is used when visibility is less than one nautical mile – or approximately two kilometres. If visibility is greater than that, but is still reduced, it is considered mist or haze. It is important to note that foggy conditions are reported on land only if visibility is less than half a nautical mile (about one kilometre). So boaters may encounter fog near coastal areas even if it is not mentioned in land-based forecasts – or particularly heavy fog, if it is. Fog Caused Worst Maritime Disaster in Canadian History The worst maritime accident in Canadian history took place in dense fog in the early hours of the morning on May 29, 1914, when the Norwegian coal ship Storstadt collided with the Canadian Pacific ocean liner Empress of Ireland. More than 1,000 people died after the Liverpool-bound liner was struck in the side and sank less than 15 minutes later in the frigid waters of the St. Lawrence River near Rimouski, Quebec. The Captain of the Empress told an inquest that he had brought his ship to a halt and was waiting for the weather to clear when, to his horror, a ship emerged from the fog, bearing directly upon him from less than a ship’s length away. -

NATS 101 Section 13: Lecture 22 Fronts

NATS 101 Section 13: Lecture 22 Fronts Last time we talked about how air masses are created. When air masses meet, or clash, the transition zone is called a front. The concept of “fronts” in weather developed from the idea of the front line of battle, specifically in Europe during World War I How are weather fronts analogous to battle fronts in a war? Which air mass “wins” depends on what type of front it is. Four types of fronts COLD FRONT: Cold air overtakes warm air. B to C WARM FRONT: Warm air overtakes cold air. C to D OCCLUDED FRONT: Cold air catches up to the warm front. C to Low pressure center STATIONARY FRONT: No movement of air masses. A to B Fronts and Extratropical Cyclones Feb. 24, 2007 Case In mid-latitudes, fronts are part of the structure of extratropical cyclones. Extratropical cyclones form because of the horizontal temperature gradient. How are they a part of the general circulation? Type of weather and air masses in relation to fronts: Feb. 24, 2007 case mPmP cPcP mTmT Characteristics of a front 1. Sharp temperature changes over a short distance 2. Changes in moisture content 3. Wind shifts 4. A lowering of surface pressure, or pressure trough 5. Clouds and precipitation We’ll see how these characteristics manifest themselves for fronts in North America using the example from Feb. 2007… COLDCOLD FRONTFRONT Horizontal extent: About 50 km AHEAD OF FRONT: Warm and southerly winds. Cirrus or cirrostratus clouds. Called the warm sector. AT FRONT: Pressure trough and wind shift. -

Weather Elements (Air Masses, Fronts & Storms)

Weather Elements (air masses, fronts & storms) S6E4. Obtain, evaluate and communicate information about how the sun, land, and water affect climate and weather. A. Analyze and interpret data to compare and contrast the composition of Earth’s atmospheric layers (including the ozone layer) and greenhouse gases. B. Plan and carry out an investigation to demonstrate how energy from the sun transfers heat to air, land, and water at different rates. C. Develop a model demonstrating the interaction between unequal heating and the rotation of the Earth that causes local and global wind systems. D. Construct an explanation of the relationship between air pressure, fronts, and air masses and meteorological events such as tornados of thunderstorms. E. Analyze and interpret weather data to explain the effects of moisture evaporating from the ocean on weather patterns weather events such as hurricanes. Term Info Picture air mass A body of air that is made of air that has the same temperature, humidity and pressure. tropical air mass A mass of warm air. If it forms over the continent it will be warm and dry. If it forms over the oceans it will be warm and moist/humid. polar air mass A mass of cold air. If it forms over the land it will be cold and dry. If it forms over the oceans it will be cold and wet. weather front Where two different air masses meet. It is often the location of weather events. warm front An advancing mass of warm air. It is a low pressure system. The warm air is replacing a cold air mass and causes rain, sleet or snow. -

ESCI 107 – the Atmosphere Lesson 13 – Fronts and Midlatitude Cyclones

ESCI 107 – The Atmosphere Lesson 13 – Fronts and Midlatitude Cyclones Reading: Meteorology Today , Chapters 11 and 12 GENERAL A front is a boundary between two air masses. ο Usually there is a sharp temperature contrast across a front. ο There is often also a contrast in moisture across a front. ο There is a shift in wind direction across a front. Because the two air masses have different temperatures and different humidities they are of different density. The lighter air mass will overrun the denser air mass, which causes lifting along the frontal zone. This is why fronts are associated with clouds and precipitation. Because air masses are associated with areas of high pressure, and fronts separate these air masses, fronts themselves lie in regions of low pressure, or troughs. THE POLAR FRONT The polar front is a nearly continuous front that separates the polar easterly winds from the midlatitude westerlies. The position of the polar front is closely approximated by the position of the polar jet stream When a low-pressure system forms on the polar front then ο on the west side of the low, cold air is pushed southward as a cold front ο on the east side of the low, warm air is pushed northward as a warm front WARM FRONTS Warm air advances into region formerly covered by cold air. Weather map symbol is red line with circular teeth. Warm air rides up and over cold air. The frontal surface slopes very shallowly with height (about 1:200). The front moves forward at 15 - 20 mph. -

PHAK Chapter 12 Weather Theory

Chapter 12 Weather Theory Introduction Weather is an important factor that influences aircraft performance and flying safety. It is the state of the atmosphere at a given time and place with respect to variables, such as temperature (heat or cold), moisture (wetness or dryness), wind velocity (calm or storm), visibility (clearness or cloudiness), and barometric pressure (high or low). The term “weather” can also apply to adverse or destructive atmospheric conditions, such as high winds. This chapter explains basic weather theory and offers pilots background knowledge of weather principles. It is designed to help them gain a good understanding of how weather affects daily flying activities. Understanding the theories behind weather helps a pilot make sound weather decisions based on the reports and forecasts obtained from a Flight Service Station (FSS) weather specialist and other aviation weather services. Be it a local flight or a long cross-country flight, decisions based on weather can dramatically affect the safety of the flight. 12-1 Atmosphere The atmosphere is a blanket of air made up of a mixture of 1% gases that surrounds the Earth and reaches almost 350 miles from the surface of the Earth. This mixture is in constant motion. If the atmosphere were visible, it might look like 2211%% an ocean with swirls and eddies, rising and falling air, and Oxygen waves that travel for great distances. Life on Earth is supported by the atmosphere, solar energy, 77 and the planet’s magnetic fields. The atmosphere absorbs 88%% energy from the sun, recycles water and other chemicals, and Nitrogen works with the electrical and magnetic forces to provide a moderate climate. -

Air Masses and Fronts

Chapter 8 AIR MASSES AND FRONTS The day-to-day fire weather in a given area depends, to a large extent, on either the character of the prevailing air mass, or the interaction of two or more air masses. The weather within an air mass—whether cool or warm, humid or dry, clear or cloudy—depends on the temperature and humidity structure of the air mass. These elements will be altered by local conditions, to be sure, but they tend to remain overall characteristic of the air mass. As an air mass moves away from its source region, its characteristics will be modified, but these changes, and the resulting changes in fire weather, are gradual from day to day. When one air mass gives way to another in a region, fire weather may change abruptly—sometimes with violent winds—as the front, or leading edge of the new air mass, passes. If the frontal passage is accompanied by precipitation, the fire weather may ease. But if it is dry, the fire weather may become critical, if only for a short time. 127 AIR MASSES AND FRONTS In chapter 5 we learned that in the primary is called an air mass. Within horizontal layers, the and secondary circulations there are regions where temperature and humidity properties of an air mass high-pressure cells tend to form and stagnate. are fairly uniform. The depth of the region in Usually, these regions have uniform surface which this horizontal uniformity exists may vary temperature and moisture characteristics. Air from a few thousand feet in cold, winter air masses within these high-pressure cells, resting or moving to several miles in warm, tropical air masses. -

Chapter 18: Thunderstorm Thunderstorm • Thunderstorms, Also Called Cumulonimbus Clouds, Are Tall, Vertically Developed Clouds That Produce Lightning and Thunder

3/14/2019 Chapter 18: Thunderstorm Thunderstorm • Thunderstorms, also called cumulonimbus clouds, are tall, vertically developed clouds that produce lightning and thunder. • The majority of thunderstorms are not severe. • The National Weather Service reserves the word “severe” for thunderstorms that have potential to threaten live and property from wind or hail. • A thunderstorm is considered severe if: (1) Hail with diameter of three-quarter inch or larger, or • Airmass Thunderstorm (2) Wind damage or gusts of 50 knots (58mph) or greater, or • Mesoscale Convective Systems (3) A tornado. • Frontal Squall Lines • Supercell Thunderstorm Locations of Severe Weather Events (in 2006) Four Elements for Severe Thunderstorms (1) A source of moisture (2) A conditionally unstable atmosphere (3) A mechanism to tiger the thunderstorm updraft either through lifting or heating of the surface (4) Vertical wind shear: a rapid change in wind speed and/or wind direction with altitude most important for developing destructive thunderstorms 1 3/14/2019 Lifting Squall Line • In cool season (late fall, winter, and early spring), lifting occurs along boundaries between air masses fronts Squall: “a violent burst of wind” • When fronts are more distinct, very long lines of thunderstorms can Squall Line: a long line of develop along frontal boundaries frontal squall lines. thunderstorms in which adjacent thunderstorm cells are so close • In warm season (late spring, summer, early fall), lifting can be provide together that the heavy by less distinct boundaries, such as the leading edge of a cool air outflow precipitation from the cell falls in coming from a dying thunderstorm. a continuous line.