Transcribing Al Grey: a Legacy Defined by Thirteen Improvisations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duke Ellington Kyle Etges Signature Recordings Cottontail

Duke Ellington Kyle Etges Signature Recordings Cottontail. Cottontail stands as a fine example of Ellington’s “Blanton-Webster” years, where the band was at its peak in performance and popularity. The “Blanton-Webster” moniker refers to bassist Jimmy Blanton and tenor saxophonist Ben Webster, who recorded Cottontail on May 4th, 1940 alongside Johnny Hodges, Barney Bigard, Chauncey Haughton, and Harry Carney on saxophone; Cootie Williams, Wallace Jones, and Ray Nance on trumpet; Rex Stewart on cornet; Juan Tizol, Joe Nanton, and Lawrence Brown on trombone; Fred Guy on guitar, Duke on piano, and Sonny Greer on drums. John Hasse, author of The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington, states that Cottontail “opened a window on the future, predicting elements to come in jazz.” Indeed, Jimmy Blanton’s driving quarter-note feel throughout the piece predicts a collective gravitation away from the traditional two feel amongst modern bassists. Webster’s solo on this record is so iconic that audiences would insist on note-for-note renditions of it in live performances. Even now, it stands as a testament to Webster’s mastery of expression, predicting techniques and patterns that John Coltrane would use decades later. Ellington also shows off his Harlem stride credentials in a quick solo before going into an orchestrated sax soli, one of the first of its kind. After a blaring shout chorus, the piece recalls the A section before Harry Carney caps everything off with the droning tonic. Diminuendo & Crescendo in Blue. This piece is remarkable for two reasons: Diminuendo & Crescendo in Blue exemplifies Duke’s classical influence, and his desire to write more grandiose pieces with more extended forms. -

History of the Drum Set

History of the Drum Set The drum set is as American as baseball, hotdogs, and apple pie. The instrument as it currently exists has seen a great deal of evolution and development. From its infancy at the start of the 20 th century to the innovations that are currently taking place, it has developed into the most visible and widely used instruments in the percussion family. Late 1800’s Brass bands were the most common type of instrumental ensemble in the United States in the later half of the 19 th century. Every town in America had bandstands were concerts were held and perhaps the reason for their existence can be attributed in part to the Civil War. Every military unit had its own squad of musicians, usually formed according to locality. Occasionally some bands stayed together after the war, while others disbanded. Each brass band consisted of two or more drummers that played snare, bass, and cymbals. In addition to marching parade commitments, these bands sometimes moved “indoors” entertaining patrons in concert providing music for occasions such as picnics and town socials. When these groups moved inside, the standard instrumentation was cut down somewhat for practical reasons. Because of this, the need for two or more drummers decreased and resourceful inventions began to flourish. The concept of one drummer playing two or more rhythms was made possible through the creation of the snare drum stand and bass drum pedal. Before the snare stand, drummers would hang the drum from their shoulder with a strap or sling, or position the drum on a chair. -

Trumpeter Scotty Barnhart Appointed New Director of the Count Basie Orchestra

September 23, 2013 To: Listings/Critics/Features From: Jazz Promo Services Press Contact: Jim Eigo, [email protected] www.jazzpromoservices.com Trumpeter Scotty Barnhart Appointed New Director of The Count Basie Orchestra For Immediate Release The Count Basie Orchestra and All That Music Productions, LLC, is pleased to announce the appointment of Scotty Barnhart as the new Director of The Legendary Count Basie Orchestra. He follows Thad Jones, Frank Foster, Grover Mitchell, Bill Hughes, and Dennis Mackrel in leading one of the greatest and most important jazz orchestras in history. Founded in 1935 by pianist William James Basie (1904-1984), the orchestra still tours the world today and is presently ending a two-week tour in Japan. The orchestra has released hundreds of recordings, won every respected jazz poll in the world at least once, has appeared in movies, television shows and commercials, Presidential Inaugurals, and has won 18 Grammy Awards, the most for any jazz orchestra. Many of its former members are some of the most important soloists, vocalists, composers, and arrangers in jazz history. That list includes Lester Young, Billie Holiday, Harry “Sweets” Edison, Jo Jones, Frank Foster, Frank Wess, Thad Jones, Joe Williams, Sonny Payne, Snooky Young, Al Grey, John Clayton, Dennis Mackrel and others. Mr. Barnhart, born in 1964, is a native of Atlanta, Georgia. He discovered his passion for music at an early age while being raised in Atlanta's historic Ebenezer Baptist Church where he was christened by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.He has been a featured trumpet soloist with the Count Basie Orchestra for the last 20 years, and has also performed and recorded with such artists as Wynton Marsalis, Marcus Roberts, Frank Sinatra, Diana Krall, Clark Terry, Freddie Hubbard, The Duke Ellington Orchestra, Nat Adderley, Quincy Jones, Barbara Streisand, Natalie Cole, Joe Williams, and many others. -

January 1988

VOLUME 12, NUMBER 1, ISSUE 99 Cover Photo by Lissa Wales Wales PHIL GOULD Lissa In addition to drumming with Level 42, Phil Gould also is a by songwriter and lyricist for the group, which helps him fit his drums into the total picture. Photo by Simon Goodwin 16 RICHIE MORALES After paying years of dues with such artists as Herbie Mann, Ray Barretto, Gato Barbieri, and the Brecker Bros., Richie Morales is getting wide exposure with Spyro Gyra. by Jeff Potter 22 CHICK WEBB Although he died at the age of 33, Chick Webb had a lasting impact on jazz drumming, and was idolized by such notables as Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich. by Burt Korall 26 PERSONAL RELATIONSHIPS The many demands of a music career can interfere with a marriage or relationship. We spoke to several couples, including Steve and Susan Smith, Rod and Michele Morgenstein, and Tris and Celia Imboden, to find out what makes their relationships work. by Robyn Flans 30 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Yamaha drumkit. 36 EDUCATION DRIVER'S SEAT by Rick Mattingly, Bob Saydlowski, Jr., and Rick Van Horn IN THE STUDIO Matching Drum Sounds To Big Band 122 Studio-Ready Drums Figures by Ed Shaughnessy 100 ELECTRONIC REVIEW by Craig Krampf 38 Dynacord P-20 Digital MIDI Drumkit TRACKING ROCK CHARTS by Bob Saydlowski, Jr. 126 Beware Of The Simple Drum Chart Steve Smith: "Lovin", Touchin', by Hank Jaramillo 42 Squeezin' " NEW AND NOTABLE 132 JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP by Michael Lawson 102 PROFILES Meeting A Piece Of Music For The TIMP TALK First Time Dialogue For Timpani And Drumset FROM THE PAST by Peter Erskine 60 by Vic Firth 104 England's Phil Seamen THE MACHINE SHOP by Simon Goodwin 44 The Funk Machine SOUTH OF THE BORDER by Clive Brooks 66 The Merengue PORTRAITS 108 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC by John Santos Portinho A Little Can Go Long Way CONCEPTS by Carl Stormer 68 by Rod Morgenstein 80 Confidence 116 NEWS by Roy Burns LISTENER'S GUIDE UPDATE 6 Buddy Rich CLUB SCENE INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS 128 by Mark Gauthier 82 Periodic Checkups 118 MASTER CLASS by Rick Van Horn REVIEWS Portraits In Rhythm: Etude #10 ON TAPE 62 by Anthony J. -

1993 February 24, 25, 26 & 27, 1993

dF Universitycrldaho LIoNEL HmPToN/CHEVRoN JnzzFrsrr\Al 1993 February 24, 25, 26 & 27, 1993 t./¡ /ìl DR. LYNN J. SKtNNER, Jazz Festival Executive Director VtcKt KtNc, Program Coordinator BRTNoR CAtN, Program Coordinator J ¡i SusnN EHRSTINE, Assistant Coordinator ltl ñ 2 o o = Concert Producer: I É Lionel Hampton, J F assisted by Bill Titone and Dr. Lynn J. Skinner tr t_9!Ð3 ü This project is supported in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts We Dedicate this 1993 Lionel Hømpton/Chevron Jøzz Festivül to Lionel's 65 Years of Devotion to the World of Juzz Page 2 6 9 ll t3 r3 t4 l3 37 Collcgc/Univcrsity Compctition Schcdulc - Thursday, Feh. 25, 1993 43 Vocal Enserrrbles & Vocal Conrbos................ Harnpton Music Bldg. Recital Hall ...................... 44 45 46 47 Vocal Compctition Schcrlulc - Fridav, Fcli. 2ó, 1993 AA"AA/AA/Middle School Ensenrbles ..... Adrrrin. Auditoriunr 5l Idaho Is OurTenitory. 52 Horizon Air has more flights to more Northwest cities A/Jr. High/.Ir. Secondary Ensenrbles ........ Hampton Music Blclg. Recital Hall ...............,...... 53 than any other airline. 54 From our Boise hub, we serve the Idaho cities of Sun 55 56 Valley, Idaho Falls, Lewiston, MoscowÆullman, Pocatello and AA/A/B/JHS/MIDS/JR.SEC. Soloists ....... North Carnpus Cenrer ll ................. 57 Twin Falls. And there's frequent direct service to Portland, lnstrurncntal Corupctilion'Schcrlulc - Saturday, Fcll. 27, 1993 Salt Lake City, Spokane and Seattle as well. We also offer 6l low-cost Sun Valley winter 8,{. {ÀtûåRY 62 and summer vacation vt('8a*" å.t. 63 packages, including fOFT 64 airfare and lodging. -

Buddy Rich Ex- to the Art

BUDDY RICH MEMORIAL CONCERT MANHATTAN CENTER FOR THE ARTS/HAMMERSTEIN BALLROOM E V E N T PROGRAM O C T O BE R 18, 2008 Buddy_Program.indd 1 10/10/08 4:59:23 PM BUDDY RICH Arguably the greatest jazz drummer of all time, the legendary Buddy Rich ex- hibited his love for music through his life-long dedication to the art. His was a career that spanned seven decades, beginning when he was just 18 months old, and continuing until his death in 1987. Immensely gifted, Rich could play with remarkable speed and dexterity despite his never having received a formal lesson and refusing to practice outside of his performances. Born Bernard Rich to vaudevillians Robert and Bess Rich on September 30, 1917, the famed drummer was introduced to audiences at a very young age. By 1921, he was a seasoned solo performer with his vaudeville act, “Traps The Drum Wonder.” With his natural sense of rhythm, Rich was per- forming regularly on Broadway by the age of four. At the peak of Rich’s early career, he was the second-highest paid child entertainer in the world. “Rich’s technique has been one of the most standardized and coveted in drumming. His dexterity, speed, and smooth execution are considered holy grails of drum tech- nique. While Rich typically held his sticks using ‘traditional grip’ (left thump facing up), he was also a skilled ‘match grip’ player, and was one of few drummers to master the one-handed roll on both hands. Some of his more spectacular moves are crossover riffs, where he would criss-cross his arms from one drum to another, sometimes over the arm, and even under the arm at great speed.” — ExcERPTED FROM WIKIPEDIA Buddy_Program.indd 2 10/10/08 4:59:26 PM Rich’s jazz career began in 1937 when he began playing BUDDY RICH with Joe Marsala at New York’s Hickory House. -

Jazz Legacy CD PDF:Steve Smith Drum Legacy.Qxd

Steve Smith Jazz Legacy Live On Tour Steve Smith - drumset Andy Fusco - alto sax, shaker Walt Weiskopf - tenor sax, soprano sax, flute, claves Mark Soskin – piano, Fender Rhodes, maracas Baron Browne - bass Produced by Steve Smith Executive Producers: Paul Siegel and Rob Wallis Recorded live at Catalina Bar and Grill, Hollywood CA October 5-8, 2006 by Robert M. Biles Mixed October 9-12, 2006 by Robert M. Biles at Bob’s Hardware, Silverlake CA Edited by Manoj Gopinath Mastered February 2008 by Jim Brick at Absolute Audio, Atlantic Highlands NJ Photos by Tim Ellis and Rick Malkin Design by Joe Bergamini This recording is dedicated to our dear friend Steve Marcus. Special Thanks to: Extra Special thanks to my wife Diane Kiernan- Janet Williamson, Bob Biles, Tim Ellis, Mike Smith for your open attitude, warm heart and Thomas, Marko Marcinko, Tommy Coster unwavering support for the band and me. Jr., Colleen Williams, Catalina Popescu, Manny Santiago, Mark Griffith, my friends www.vitalinformation.com/steve http://www.myspace.com/stevesmithjazzlegacy at Hudson Music: Paul Siegel and Rob Wal- www.marksoskin.com lis, Zildjian: Cragie and Debbie Zildjian, www.waltweiskopf.com John DeChristopher, Paul Francis, John King, and Bob Wiczling, Sonor: Karl-Heinz Baron Browne uses Gallien-Krueger bass amps. Menzel and Thomas Barth, Vic Firth: Marco Soccoli, Vic and Tracy Firth, Remo: Matt For booking: Connors, DW pedals: Don Lombardi, Shure: Janet Williamson Music Agency Ryan Smith, Puresound Percussion: Hugh PO Box 27114 Gilmartin, Michael Bloom and Steve Orkin. Los Angeles, CA 90027 [email protected] www.janetwilliamsonmusicagency.com Copyright © 2008 Hudson Music LLC All Rights Reserved www.hudsonmusic.com Live On Tour 1. -

Basic Was One of Rich Was Stricken with a There Is a Tie of Affection

well 'gain. And Basic was one of the first to telephone after be surprising. But coming from the modern camp, it is, in Rich was stricken with a heart attack in November. a sense. For Rich hasn’t always been kind to them in his There is a tie of affection between Basie and Rich that comments. During the early days of bebop, he expressed gives many persons the idea that Rich once was employed disdain for the new drummers, saying they had no right to by Basie. Actually, Rich only played as fill-in drummer break up the rhythmic flow of a band with constant explo with the band for two weeks after Jo Jones was drafted in sions and extraneous back beats. To him. drums constituted 1944. a complete instrument, designed to set and hold the beat, B.-'ie was playing the Club Plantation in Los Angeles at and even when throwing in explosions, he would never sacri that time. Rich was in Culver City, making a movie with fice rhythmic continuity. He felt the modernists were sacri Tommy Dorsey on the M-G-M lot. To help Basie, Buddy ficing the essential reason for drums in order to get a new worked every evening with the band after working from sound. b a.m. to 5 p.m. at M-G-M But time has mellowed Rich’s views on drummers, along For some reason, Basie and Rich never got around to with his playing, which is more restrained than it was in discussing money. After two weeks, a regular substitute the days of the Granz tours. -

Title Arranger / Composer Arranger / Composer

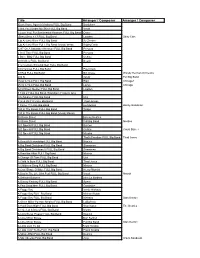

Title Arranger / Composer Arranger / Composer (Back Home Again In) Indiana FULL Big Band Barduhn+ (I Got You) Under My Skin FULL Big Band Vocal (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons FULL Big Band Osser (Shes) Sexy + 17 FULL Big Band Lowden Stray Cats (Up A) Lazy River FULL Big Band Sy Zentner (Up A) Lazy River FULL Big Band (Vocal) Wess Bobby Darin 1237 On A Saturday Afternoon FULL Big Band Persons 2 At A Time FULL Big Band Persons 2 Bone BBQ FULL Big Band Cobine 20 Nickles FULL Big Band Beach 21st Century Schizoid Man FULL Big Band 23 Chuckles FULL Big Band Paul Clark 23 Red FULL Big Band Bill Chase Woody Herman Orchestra 23o N 82oW Full Big Band 25 Or 6 To 4 FULL Big Band Blair Chicago+ 25 Or 6 To 4 FULL Big Band Lamm Chicago 42nd Street Medley FULL Big Band Lowden 5 Foot 2 FULL Big Band (Trombone Feature) Amy 50's Medley FULL Big Band Unk 61st & Rich' It FULL Big Band Thad Jones+ 7 Come 11 FULL Big Band Henderson Benny Goodman 720 In The Books FULL Big Band Wolpe 720 In The Books FULL Big Band (Vocal) Mason 88 Basie Street Sammy Nestico 88 Basie Street Full Big Band Nestico 920 Special FULL Big Band Bunton 920 Special FULL Big Band Collins Count Basie+ 920 Special FULL Big Band Murphy A That's Freedom FULL Big Band Thad Jones A Beautiful Friendship FULL Big Band Nestico A Big Band Christmas FULL Big Band Strommen A Big Band Christmas II FULL Big Band Strommen A Brazilian Affair FULL Big Band Mintzer A Change Of Pace FULL Big Band Unk A Child Is Born FULL Big Band Thad Jones A Childrens Song FULL Big Band Mintzer A Cool Shade Of Blue -

Album Releases Feb. Album Releases

) —— — ) ) — )) ) ) —— ALBUM RELEASES FEB. ALBUM RELEASES llllll!llllll!llll!l!llll!llll!llillllll!llllll!!l!llllll!lll!IIIII!lllll , , CORAL “Al Casey Quartet” —Moodsville Vol. 12 SAVOY “Midnight Special”— Al Smith — Bluesville 1013 “No More In Life” — Mildred Anderson— Bluesville POPULAR Pete Fountain’s French Quartet New Orleans” “The Fabulous Jimmy Scott”—#121 50 ( M 1017 CRL-57359(M) CRL-757359(S) 1 1 ( — “Candy And Big Maybelle” — # 401 M “Just Blues” —Memphis Slim —Bluesville 1018 Songs Everybody Knows” Teresa CRL- — Brewer— Lightning”-— Lightning Hopkins Bluesville 1019 — | 57361 (M) CRL-757361 — (S) Bud Freeman All Stars w/Shorty Baker”—Swing- Royal Caledonian Pipe Band” Pipe Major- ABC—PARAMOUNT — vill 2012 David Fairweather CRL-57318(M) TELEFUNKEN — Stasch”—Coleman Hawkins w/Prestige Blues The Irish World of Patrick O’Hagan” CRL-57316 “Dedicated To You” Ray Charles ABC-355(M) — Swingers Swingville 2013 — — (M) “Music For Lovers”—Werner Muller and His Or- — ABCS-3551S) Tate-A-Tate” —Buddy Tate w/Clark Terry Swing- ‘Come All Ye’s And Other Irish Songs” Pat Har- chestra—TP-251 6(M)—TPS-1 251 6(S) — “The Giants of Flamenco’’ Montoya & Sabicas — ville 2014 — rington— CRL-57367(M) “Beer ’N Brass” —Bohemian Polkas & Waltzes ABC-357IM) The Best of Ewan MacColl” — Prestige Int’l. 13004 ‘Irish Show Boat”—The McNulty Family—CRL- Ernst Mosch & His Bohemian Band—TP-251 5(M) “Adventures In Paradise (Vol. II)’’ Various Art- The Best of Peggy Seeger” Prestige Int'l. — 57368(M) — 13005 ists—ABC-3581 M) —ABCS-358(S) Jeannie Robertson—World’s Greatest Folk Singer” ‘Irish Jigs And Reels”—Michael Coleman CRL- “Big 15 Various Artists ABC-359(M) — —Prestige Int’l. -

Bandinfo English 2018.Indd

Jazz, from New Orleans to Swing, presented in an entirely original form by the leading Classic Jazz group in Germany: BARRELHOUSE JAZZBAND www.barrelhouse-jazzband.com Founded in 1953 and active ever since, the BARRELHOUSE JAZZBAND has gai- ned national and international renown and ranks among the top groups of the Euro- pean scene. The BARRELHOUSE JAZZBAND presents a special blend of elements from all phases of traditional jazz, with predominant accents from the early big band style of the twenties, the small band style around 1930 and the New Orleans Renaissance. All numbers are played in new original arrangements. The band also plays many original titles written by members of the band. Some of them became very popular, like „The Barrelhouse Showboat“ and „Take Us To The Mardi Gras“ (by Horst Schwarz). The band has toured more than 50 countries on 4 continents and appeared at all major jazz festivals in Europe, e.g. The Hague, Breda, Nice, Paris, San Sebastian, Ascona, Zurich, Lucerne, Cracow, Cork, Birmingham, Copenhagen, Oslo, Berlin and many more. When the Barrelhouse Jazzband played at the New Orleans Jazz Festival - rits, received the honorary citizenship of the birthplace of jazz. in1968, they were one of the first bands from Europe who, in recognition of their me The band has recorded more than 30 albums and has received - beside other awards - the „German Phono Academy Award“ for the Best Traditional Jazz Record of the year (Quotation: „Highly intelligent old jazz, full of vitality, enlightened music, al- ways with that beautiful black feeling“). Eubie Blake, the famous ragtime pianist and composer, heard the band and commented: „Everything that I write I mean from the bottom of my heart: This is one of the best for a small orchestra that I have ever heard. -

1959 Jazz: a Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959

GELB, GREGG, DMA. 1959 Jazz: A Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959. (2008) Directed by Dr. John Salmon. 69 pp. Towards the end of the 1950s, about halfway through its nearly 100-year history, jazz evolution and innovation increased at a faster pace than ever before. By 1959, it was evident that two major innovative styles and many sub-styles of the major previous styles had recently emerged. Additionally, all earlier practices were in use, making a total of at least ten actively played styles in 1959. It would no longer be possible to denote a jazz era by saying one style dominated, such as it had during the 1930s’ Swing Era. This convergence of styles is fascinating, but, considering that many of the recordings of that year represent some of the best work of many of the most famous jazz artists of all time, it makes 1959 even more significant. There has been a marked decrease in the jazz industry and in stylistic evolution since 1959, which emphasizes 1959’s importance in jazz history. Many jazz listeners, including myself up until recently, have always thought the modal style, from the famous 1959 Miles Davis recording, Kind of Blue, dominated the late 1950s. However, a few of the other great and stylistically diverse recordings from 1959 were John Coltrane’s Giant Steps, Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz To Come, and Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, which included the very well- known jazz standard Take Five. My research has found many more 1959 recordings of equally unique artistic achievement.