The Dating of the Fourth Volume of Guillaume-Antoine Olivier's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Envenomations in Humans Caused by The

linica f C l To o x l ic a o n r l o u g o y J Amaral et al., J Clin Toxicol 2018, 8:4 Journal of Clinical Toxicology DOI: 10.4172/2161-0495.1000392 ISSN: 2161-0495 Case Report Open Access Envenomations in Humans Caused by the Venomous Beetle Onychocerus albitarsis: Observation of Two Cases in São Paulo State, Brazil Amaral ALS1*, Castilho AL1, Borges de Sá AL2 and Haddad V Jr3 1Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP, CEP 18618-000, Botucatu, São Paulo State, Brazil 2Private Clinic, Botucatu, São Paulo State, Brazil 3Departamento de Dermatologia e Radioterapia, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP, CP 557, CEP 18618-000, Botucatu, São Paulo State, Brazil *Corresponding author: Antonio L. Sforcin Amaral, Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP, CEP 18618-000, Botucatu, São Paulo State, Brazil, Email: [email protected] Received date: July 23, 2018; Accepted date: August 21, 2018; Published date: August 24, 2018 Copyright: ©2018 Amaral ALS, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Beetles (Coleoptera) are the most diverse group of animals in the world and occur in many environments. In Atlantic and Amazon rainforests, the scorpion-beetle Onychocerus albitarsis (Cerambycidae), can be found. It has venom glandules and inoculators organs in the antenna extremities. Two injuries in humans are reported, showing different patterns of skin reaction after the stings. -

11-16589 PRA Record Saperda Candida

PRA Saperda candida 11-16589 (10-15760, 09-15659) European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation Organisation Européenne et Méditerranéenne pour la Protection des Plantes Guidelines on Pest Risk Analysis Decision-support scheme for quarantine pests Version N°3 Pest Risk Analysis for Saperda candida Pest risk analysts: Expert Working group for PRA for Saperda candida (met in 2009-11) ANDERSON Helen (Ms) - The Food and Environment Research Agency (GB) AGNELLO Arthur (Mr) - Department of Entomology New York State Agricultural Experiment Station(USA) BAUFELD Peter (Mr) - Julius Kühn Institut (JKI), Federal Research Centre for Cultivated Plants, Institute for National and International Plant Health (DE) GILL Bruce D. (Mr) - Head Entomology, Ottawa Plant Laboratories, C.F.I.A. (CA) PFEILSTETTER Ernst (Mr) - Julius Kühn Institut (JKI), Federal Research Centre for Cultivated Plants, Institute for National and International Plant Health (DE) (core member) STEFFEK Robert (Mr) - Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety (AGES), Institute for Plant Health (AT) (core member) VAN DER GAAG Dirk Jan (Mr) - Plant Protection Service (NL) (core member) The Section on risk management was reviewed by the EPPO Panel on Phytosanitary Measures in 2010-02-18. 1 PRA Saperda candida Stage 1: Initiation 1 Identification of a In summer 2008, the presence of Saperda candida was detected for the first time in Germany and in Europe (Nolte & Give the reason for performing the PRA single pest Krieger, 2008). This wood boring insect was observed on the island of Fehmarn on urban trees ( Sorbus intermedia and other host plants) and eradication measures were taken against it. S. candida is considered as a pest of apple trees and other tree species in North America. -

Faune De Belgique / Fauna Van België

Faune de Belgique / Fauna van Belgi Bulletin de la Société royale belge d’Entomologie/Bulletin van de Koninklijke Belgische Vereniging voor Entomologie, 153 (2017): 15–20 Donacia crassipes Fabricius, 1775 a rare or a neglected species in Belgium? (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Donaciinae) Kevin S CHEERS 1,2 , Edward V ERCRUYSSE 2, Vincent SMEEKENS 2 & Steven DE SAEGER 2 1 Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO), Kliniekstraat 25, 1070 Brussels, Belgium Abstract Donacia crassipes Fabricius, 1775 is an easily recognizable species of reed beetles (Donaciinae). The species is associated with Nymphaeaceae (both Nymphaea and Nuphar species). The species was not uncommon in Belgium until 1950, afterwards a notable decline was seen in the number of known records and from 1950 onwards only five records are known. A survey was carried out to assess the present status and distribution of the species in Belgium. 47 sites in the north of Belgium with stable populations of Nymphaeaceae were checked for the presence of D. crassipes . Of these sampled sites D. crassipes was present at 35 (74,5%) and thus the species seems currently not as rare as recent records indicated. This species was encountered for the first time in the province Limburg. Furthermore we present the first records of D. crassipes on non-indigenous water-lilies ( Nymphaea cultivars). Keywords : Donacia crassipes , Donaciinae , water beetle, reed beetle, Belgium, neglected species, Nymphaeaceae, water lilies Samenvatting Donacia crassipes Fabricius, 1775 is een relatief makkelijk herkenbaar riethaantje (Donaciinae). De soort is gebonden aan vegetaties van Nymphaeaceae (zowel Nymphaea en Nuphar soorten). -

(Coleoptera Chrysomelidae Donaciinae) in the Malay Archipelago

Bulletin S.RB.E.IKB. V.E., 136 (2000) : 44-52 Observations on Donacia (Cyphogasier) javana WIEDEMAN, 1821 (Coleoptera Chrysomelidae Donaciinae) in the Malay Archipelago by Pascal LAYS Rue F. Desoer 34, B-4031 Liege, Belgium. Summary Some faunistical and biological observations were made in Singapore and the Philippines (Minda nao) (Philippines fauna nov.) on Donacia (Cyphogaster) javana WIEDEMAN, 1821 (Coleoptera Chry somelidae Donaciinae). Nymphaea pubescens WILLDENOW (Nymphaeaceae) appears to be Donacia javana's food plant. Keywords : Chrysomelidae, Donaciinae, Faunistics, Singapore, Philippines, Mindanao, Nymphaea. Resume Quelques observations faunistiques et biologiques ont ete realisees a Singapour et aux Philippines (Mindanao) (Philippines fauna nov.) sur Donaciajavana WIEDEMAN, 1821 (Coleoptera Chrysome lidae Donaciinae). Nymphaea pubescens WILLDENOW (Nymphaeaceae) apparait etre la plante nourri ciere de Donacia javana. Introduction out : D. javana or D. lenzi SCHONFELD, 1888, two species morphologically close to each other. "' The subgenus Cyphogaster GOECKE, 1934, to I identified the specimens collected in Singapore which D. javana belongs, is easily identifiable as belonging to D. javana, but the specimens from the two other sub genera Donacia F ABRI from the Philippines were identified as belonging crus, 1775 and Donaciomima MEDVEDEV, 1973, to D. lenzi. However, having a doubt concerning composing the genus Donacia F ABRICIUS, 177 5, the identification of the latter specimens, a cou by the presence of a pair of median tubercles on ple from Mindanao (South Philippines) was sub the first ventrite of males (GOECKE, 1934 : 217). mitted to my American colleague, specialist of This subgenus, that mainly occurs in the Indo Donaciinae, Dr. I. ASKEVOLD. malayan and Australian Regions, comprises pre Based on a comparative study (including the sently seven species (ASKEVOLD, 1990 : 646; endophallus) of the submitted Mindanao speci REm, 1993), and this number could be even mens with material from Java, Singapore, South fewer (see below). -

Newsletter Dedicated to Information About the Chrysomelidae Report No

CHRYSOMELA newsletter Dedicated to information about the Chrysomelidae Report No. 55 March 2017 ICE LEAF BEETLE SYMPOSIUM, 2016 Fig. 1. Chrysomelid colleagues at meeting, from left: Vivian Flinte, Adelita Linzmeier, Caroline Chaboo, Margarete Macedo and Vivian Sandoval (Story, page 15). LIFE WITH PACHYBRACHIS Inside This Issue 2- Editor’s page, submissions 3- 2nd European Leaf Beetle Meeting 4- Intromittant organ &spermathecal duct in Cassidinae 6- In Memoriam: Krishna K. Verma 7- Horst Kippenberg 14- Central European Leaf Beetle Meeting 11- Life with Pachybrachis 13- Ophraella communa in Italy 16- 2014 European leaf beetle symposium 17- 2016 ICE Leaf beetle symposium 18- In Memoriam: Manfred Doberl 19- In Memoriam: Walter Steinhausen 22- 2015 European leaf beetle symposium 23- E-mail list Fig. 1. Edward Riley (left), Robert Barney (center) and Shawn Clark 25- Questionnaire (right) in Dunbar Barrens, Wisconsin, USA. Story, page 11 International Date Book The Editor’s Page Chrysomela is back! 2017 Entomological Society of America Dear Chrysomelid Colleagues: November annual meeting, Denver, Colorado The absence pf Chrysomela was the usual combina- tion of too few submissions, then a flood of articles in fall 2018 European Congress of Entomology, 2016, but my mix of personal and professional changes at July, Naples, Italy the moment distracted my attention. As usual, please consider writing about your research, updates, and other 2020 International Congress of Entomology topics in leaf beetles. I encourage new members to July, Helsinki, Finland participate in the newsletter. A major development in our community was the initiation of a Facebook group, Chrysomelidae Forum, by Michael Geiser. It is popular and connections grow daily. -

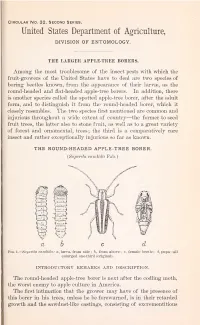

The Larger Apple-Tree Borers

Circular No. 32, Second Series. United States Department of Agriculture, DIVISION OF ENTOMOLOGY. THE LARGER APPLE-TREE BORERS. Among the most troublesome of the insect pests with which the fruit-growers of the United States have to deal are two species of boring beetles known, from the appearance of their larvse, as the round-headed and flat-headed apple-tree borers. In addition, there is another species called the spotted apple-tree borer, after the adult form, and to distinguish it from the round-headed borer, which it closely resembles. The two species first mentioned are common and injurious throughout a wide extent of country—the former to seed fruit trees, the latter also to stone fruit, as well as to a great variety of forest and ornamental, trees; the third is a comparatively rare insect and rather exceptionally injurious so far as known. THE ROUND-HEADED APPLE-TREE BORER. (Saperda Candida Fab.) Fig. 1.—Saperda Candida: a, larva, from side; b, from above; c, female beetle; d, pupa—all enlarged one-third (original). INTRODUCTORY REMARKS AND DESCRIPTION. The round-headed apple-tree borer is next after the codling moth, the worst enemy to apple culture in America. The first intimation that the grower may have of the presence of this borer in his trees, unless he be forewarned, is in their retarded growth and the sawdust-like castings, consisting of excrementitious matter and gnawings of woody fiber, which the larvae extrude from openings into their burrows. This manifestation is usually accom- panied by more or less evident discoloration of the bark, and, in early spring, particularly, slight exudation of sap. -

Additions to the Checkered Beetle Fauna of Belize with the Description of a New Species (Coleoptera: Cleridae) and a Nomenclatural Change

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida March 1995 Additions to the checkered beetle fauna of Belize with the description of a new species (Coleoptera: Cleridae) and a nomenclatural change Jacques Rifkind North Hollywood, CA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Entomology Commons Rifkind, Jacques, "Additions to the checkered beetle fauna of Belize with the description of a new species (Coleoptera: Cleridae) and a nomenclatural change" (1995). Insecta Mundi. 161. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/161 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI, Vol. 9, No. 1-2, March - June, 1995 17 Additions to the checkered beetle fauna of Belize with the description of a new species (Coleoptera: Cleridae) and a nomenclatural change Jacques Rifkind 11322 Camarillo St. #304 North Hollywood, CA 91602 USA Abstract: New information on the distribution and ecology of Cleridae in Belize, Central America is presented. Enoclerus (E.) gumae, new species, is described from Cayo District, Belize and Cymatodera pallidipennis Chevrolat 1843 is placed as a junior synonym of C. prolixa (Klug 1842). Introduction Until the early -

ES Teacher Packet.Indd

PROCESS OF EXTINCTION When we envision the natural environment of the Currently, the world is facing another mass extinction. past, one thing that may come to mind are vast herds However, as opposed to the previous five events, and flocks of a great diversity of animals. In our this extinction is not caused by natural, catastrophic modern world, many of these herds and flocks have changes in environmental conditions. This current been greatly diminished. Hundreds of species of both loss of biodiversity across the globe is due to one plants and animals have become extinct. Why? species — humans. Wildlife, including plants, must now compete with the expanding human population Extinction is a natural process. A species that cannot for basic needs (air, water, food, shelter and space). adapt to changing environmental conditions and/or Human activity has had far-reaching effects on the competition will not survive to reproduce. Eventually world’s ecosystems and the species that depend on the entire species dies out. These extinctions may them, including our own species. happen to only a few species or on a very large scale. Large scale extinctions, in which at least 65 percent of existing species become extinct over a geologically • The population of the planet is now growing by short period of time, are called “mass extinctions” 2.3 people per second (U.S. Census Bureau). (Leakey, 1995). Mass extinctions have occurred five • In mid-2006, world population was estimated to times over the history of life on earth; the first one be 6,555,000,000, with a rate of natural increase occurred approximately 440 million years ago and the of 1.2%. -

The Geographic Variation of Saperda Inornata Say (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in Eastern North America

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 4 Number 2 -- Summer 1971 Number 2 -- Summer Article 2 1971 July 2017 The Geographic Variation of Saperda Inornata Say (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in Eastern North America John C. Nord USDA Forest Service, Athens, Georgia Fred B. Knight The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Nord, John C. and Knight, Fred B. 2017. "The Geographic Variation of Saperda Inornata Say (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in Eastern North America," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 4 (2) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol4/iss2/2 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Nord and Knight: The Geographic Variation of Saperda Inornata Say (Coleoptera: Cer 1971 THE MICHIGAN ENTOMOLOGIST 39 THE GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION OF SAPERDA INORNA TA SAY (COLEOPTERA: CERAMBYCIDAE) IN EASTERN NORTH AMERICA John C. Nordl and Fred B. ~ni~ht~ During the summers of 1962 and 1963 a study of the life history and behavior of what was thought to have been Saperda moesta LeConte in trembling aspen, Populus tremuloides Michaux, was completed in northern Michigan (Nord, 1968). After the field study, it became apparent that the original identification was doubtful. Furthermore, there was a possibility that two species were present in the study areas, thus the biological data collected may have represented not one but two species. -

Management Indicator Species of the Kaibab National Forest: an Evaluation of Population and Habitat Trends Version 3.0 2010

Management Indicator Species of the Kaibab National Forest: an evaluation of population and habitat trends Version 3.0 2010 Isolated aspen stand. Photo by Heather McRae. Pygmy nuthatch. Photo by the Smithsonian Inst. Pumpkin Fire, Kaibab National Forest Mule deer. Photo by Bill Noble Red-naped sapsucker. Photo by the Smithsonian Inst. Northern Goshawk © Tom Munson Tree encroachment, Kaibab National Forest Prepared by: Valerie Stein Foster¹, Bill Noble², Kristin Bratland¹, and Roger Joos³ ¹Wildlife Biologist, Kaibab National Forest Supervisor’s Office ²Forest Biologist, Kaibab National Forest, Supervisor’s Office ³Wildlife Biologist, Kaibab National Forest, Williams Ranger District Table of Contents 1. MANAGEMENT INDICATOR SPECIES ................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 4 Regulatory Background ...................................................................................................... 8 Management Indicator Species Population Estimates ...................................................... 10 SPECIES ACCOUNTS ................................................................................................ 18 Aquatic Macroinvertebrates ...................................................................................... 18 Cinnamon Teal .......................................................................................................... 21 Northern Goshawk ................................................................................................... -

Burkholderia As Bacterial Symbionts of Lagriinae Beetles

Burkholderia as bacterial symbionts of Lagriinae beetles Symbiont transmission, prevalence and ecological significance in Lagria villosa and Lagria hirta (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) Dissertation To Fulfill the Requirements for the Degree of „doctor rerum naturalium“ (Dr. rer. nat.) Submitted to the Council of the Faculty of Biology and Pharmacy of the Friedrich Schiller University Jena by B.Sc. Laura Victoria Flórez born on 19.08.1986 in Bogotá, Colombia Gutachter: 1) Prof. Dr. Martin Kaltenpoth – Johannes-Gutenberg-Universität, Mainz 2) Prof. Dr. Martha S. Hunter – University of Arizona, U.S.A. 3) Prof. Dr. Christian Hertweck – Friedrich-Schiller-Universität, Jena Das Promotionskolloquium wurde abgelegt am: 11.11.2016 “It's life that matters, nothing but life—the process of discovering, the everlasting and perpetual process, not the discovery itself, at all.” Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Idiot CONTENT List of publications ................................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: General Introduction ....................................................................................... 2 1.1. The significance of microorganisms in eukaryote biology ....................................................... 2 1.2. The versatile lifestyles of Burkholderia bacteria .................................................................... 4 1.3. Lagriinae beetles and their unexplored symbiosis with bacteria ................................................ 6 1.4. Thesis outline .......................................................................................................... -

Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle «Grigore Antipa» Vol. 59 (2) pp. 179–194 DOI: 10.1515/travmu-2016-0025 Research paper The Catalogue of Donaciinae and Criocerinae Species (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) from the New Leaf Beetle Collection from “Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History (Bucharest) (Part I) Sanda MAICAN1, *, Rodica SERAFIM2 1Institute of Biology Bucharest of Romanian Academy, 296 Splaiul Independenţei, 060031 Bucharest, P.O. Box 56–53, Romania. 2“Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History, Kiseleff 1, 011341 Bucharest, Romania. *corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Received: August 23, 2016; Accepted: November 22, 2016; Available online: December 23, 2016; Printed: December 30, 2016 Abstract. The paper presents data on 33 palaearctic species of the Donaciinae (Donaciini, Haemoniini and Plateumarini tribes) and Criocerinae preserved in the new Chrysomelidae collection of “Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History (Bucharest). Among the valuable species preserved in this collection, Macroplea appendiculata (Panzer) and M. mutica (Fabricius) – two very rare European Donaciinae beetles, should be mentioned. Key words: Chrysomelidae, Donaciinae, Criocerinae, collections, “Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History, Bucharest. INTRODUCTION The entomological collections stored in the patrimony of “Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History of Bucharest have a historical and documentary scientific value, both at national and international level. In “Grigore Antipa” Museum, the Chrysomelidae material is included in the old Collection of Palaearctic Coleopterans (partial data published) and in the Collection of Chrysomelidae, recently formed. The new collection, which we refer in this paper, gathers: – material preserved in the old coleopteran collection from the Palaearctic area, including specimens from Richard Canisius, Deszö Kenderessy, Fridrich Deubel, Arnold Lucien Montandon and Emil Várady collections, acquired between 1883–1923.