UK-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

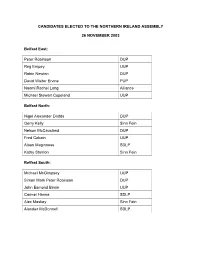

Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP

CANDIDATES ELECTED TO THE NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY 26 NOVEMBER 2003 Belfast East: Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP Belfast North: Nigel Alexander Dodds DUP Gerry Kelly Sinn Fein Nelson McCausland DUP Fred Cobain UUP Alban Maginness SDLP Kathy Stanton Sinn Fein Belfast South: Michael McGimpsey UUP Simon Mark Peter Robinson DUP John Esmond Birnie UUP Carmel Hanna SDLP Alex Maskey Sinn Fein Alasdair McDonnell SDLP Belfast West: Gerry Adams Sinn Fein Alex Atwood SDLP Bairbre de Brún Sinn Fein Fra McCann Sinn Fein Michael Ferguson Sinn Fein Diane Dodds DUP East Antrim: Roy Beggs UUP Sammy Wilson DUP Ken Robinson UUP Sean Neeson Alliance David William Hilditch DUP Thomas George Dawson DUP East Londonderry: Gregory Campbell DUP David McClarty UUP Francis Brolly Sinn Fein George Robinson DUP Norman Hillis UUP John Dallat SDLP Fermanagh and South Tyrone: Thomas Beatty (Tom) Elliott UUP Arlene Isobel Foster DUP* Tommy Gallagher SDLP Michelle Gildernew Sinn Fein Maurice Morrow DUP Hugh Thomas O’Reilly Sinn Fein * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from 15 January 2004 Foyle: John Mark Durkan SDLP William Hay DUP Mitchel McLaughlin Sinn Fein Mary Bradley SDLP Pat Ramsey SDLP Mary Nelis Sinn Fein Lagan Valley: Jeffrey Mark Donaldson DUP* Edwin Cecil Poots DUP Billy Bell UUP Seamus Anthony Close Alliance Patricia Lewsley SDLP Norah Jeanette Beare DUP* * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from -

Withdrawal Agreement) Bill

1 House of Commons NOTICES OF AMENDMENTS given up to and including Friday 3 January 2020 New Amendments handed in are marked thus Amendments which will comply with the required notice period at their next appearance Amendments tabled since the last publication: 28 to 51 and NC39 to NC66 and NS1 COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE HOUSE EUROPEAN UNION (WITHDRAWAL AGREEMENT) BILL NOTE This document includes all amendments tabled to date and includes any withdrawn amendments at the end. The amendments have been arranged in accordance with the Order of the House [20 December 2019]. CLAUSES 1 TO 6; NEW CLAUSES RELATING TO PART 1 OR 2; NEW SCHEDULES RELATING TO PART 1 OR 2 Sir Jeffrey M Donaldson Sammy Wilson Mr Gregory Campbell Jim Shannon Ian Paisley Gavin Robinson Paul Girvan Carla Lockhart 25 Clause 5,page8, line 33, at end insert— “(6) It shall be an objective of the Government, in accordance with Article 13 (8) of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland, to reach agreement on superseding the provisions of the Protocol in every respect as soon as practicable.” Member’s explanatory statement This amendment is aimed at using the existing provisions of the withdrawal agreement to remove the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol as soon as possible. 2 Committee of the whole House: 3 January 2020 European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill, continued Jeremy Corbyn Keir Starmer Paul Blomfield Thangam Debbonaire Valerie Vaz Mr Nicholas Brown Nick Thomas-Symonds Kerry McCarthy NC4 To move the following Clause— “Extension of the implementation period After section 15 of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (publication of and rules of evidence) insert— “15A Extension of the implementation period “(1) A Minister of the Crown must seek to secure agreement in the Joint Committee to a single decision to extend the implementation period by two years, in accordance with Article 132 of the Withdrawal Agreement unless one or more condition in subsection (2) is met. -

Martin Vickers MP Member Ofparliament for Cleethorpes

MARTIN VICKERS Member of Parliament for the Cleethorpes Constituency HOUSE OF COMMONS LONDON SW1A OAA Te I: 0 2 0 7 2 1 9 7 2 12 Steve Berry OBE, Department for Transport, Great Minster House, 33 Horseferry Road, London, SWl 4DR. 15 October 20 19 J)"_. f\\\t ~ ' Highways Maintenance C~ge Fund Tranche 2b Application I am pleased to offer my support for this funding application for A15 (North). The A15 (North) is a key route which connects the north and south via the Humber Bridge. It links the A63/M62 corridor and Hull in the north and the M180/M18/Ml corridor in the south as well as South Humber Gateway, which includes two of the UK's oil refineries and the Ports oflmmingham and Grimsby, which are the largest ports in the UK by tonnage. The South Humber Gateway, is an area ofnational and international economic importance. The A 15 also provides easy access to Humberside Airport and the adjacent business park and the market town of Barton upon Humber. The A15 is also a key route linking the areas covered by the sub-national transport body of Transport for the North (TfN) and Midlands Connect. TfN's Strategic Transport Plan identifies three key aims of 1) connecting people, 2) connecting businesses and 3) moving goods. Improving this section of the A15 will help to achieve these aims. The A15 is included in TfN's major road network, which includes the North's economically important roads which link the North 's important centres ofeconomic activity. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Thursday Volume 564 20 June 2013 No. 21 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 20 June 2013 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2013 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 1033 20 JUNE 2013 1034 Caroline Dinenage (Gosport) (Con): While Government House of Commons money is, of course, important, will the Minister join me in celebrating the amazing fundraising work of our Thursday 20 June 2013 museums, including the Submarine museum in Gosport, which has raised more than £6.5 million through heritage funding and lots of fundraising in order to restore The House met at half-past Nine o’clock HMS Alliance? Mr Vaizey: I am delighted to endorse what my hon. PRAYERS Friend says. There is a huge amount of philanthropy outside London and we have made it far easier to give [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] to the arts. We have invested through the Catalyst Fund in endowments and fundraising capacity. BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS 16. [160620] Hugh Bayley (York Central) (Lab): The artefacts in the science museums, including locomotives CONTINGENCIES FUND ACCOUNT 2012-13 in the National Railway museum, are expensive to Ordered, maintain and that museum is concerned it will not have That there be laid before this House an Account of the enough money for conservation, preservation, research Contingencies Fund, 2012-13, showing: and dissemination of information about its collections. (1) A Statement of Financial Position; Will the Minister address specifically that point in his (2) A Statement of Cash Flows; and evidence to the Culture, Media and Sport Committee? (3) Notes to the Accounts; together with the Certificate and Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General thereon.— Mr Vaizey: I am sure I will specifically address that (Greg Clark) point, because I am sure the Committee will ask me about it. -

New Waltham 20 A5pp Newsletter.Indd

New Waltham Village News Helping our community grow Edition This newsletter is published and distributed to every house and business August No.New 45Waltham Parish Council,within working New Waltham together by toNew improve Waltham our Parish community Council 2016 Parish Councillors for New Waltham Chairman Cllr. G. Williams 22 Albery Way, New Waltham Tel. 824050 Vice Chair Cllr. Ruth Barber 14 Savoy Court, New Waltham Other Members Cllr. George Baker 405 Louth Road, New Waltham Cllr. Roger Breed 9 Janton Court, New Waltham Cllr Julie Dolphin 8 Chandlers Close, New Waltham Cllr. Cyril Mumby 35 Dunbar Avenue, New Waltham Cllr. David Raper 17 Rutland Drive, New Waltham Cllr. Patricia Simpson 41 Peaks Lane, New Waltham Cllr. Rosemary Thompson 2 Martin Way, New Waltham Cllr. Joanne Welham 6 Greenlands Avenue, New Waltham Ward Councillors Cllr. John Fenty Tel. 07712 398656 Cllr. Steve Harness Tel. 07925 050706 Cllr. Stan Shreeve Tel. 07702 343340 MP Martin Vickers Tel. 01472 602325 for an appointment Martin holds a surgery at Waltham Library the second Saturday of each month 11:30 - 13:30 Parish Clerk Mrs Kathy Peers Tel. 01472 280290 Email: [email protected] Closing Dates for inclusion of items in Newsletter The newsletter is published quarterly in February, May, August and November. The closing date for the receipt of articles and advertisements is the 15th of the month preceding the publication. The closing date for our November newsletter is 15th October 2016 Please send articles, news and advertisements to the Parish Clerk at [email protected] New Waltham Parish Council, working together to improve our community 2 New Waltham Parish Council What has been happening and what is going to happen? We have had so much going on it is hard to At the end of 2015 following many requests know where to begin but I suppose I have from residents for decorative village signs got to begin somewhere so here goes. -

New Waltham Village News

New Waltham Village News Helping our community grow Edition This newsletter is published and distributed to every house and business August No.New 49Waltham Parish Council,within working New Waltham together by toNew improve Waltham our Parish community Council 2017 Parish Councillors for New Waltham Chairman Cllr. G. Williams 22 Albery Way, New Waltham Tel. 824050 Vice Chair Cllr. Ruth Barber 14 Savoy Court, New Waltham Other Members Cllr. George Baker 405 Louth Road, New Waltham Cllr. Roger Breed 9 Janton Court, New Waltham Cllr Julie Dolphin 8 Chandlers Close, New Waltham Cllr. Cyril Mumby 35 Dunbar Avenue, New Waltham Cllr. David Raper 17 Rutland Drive, New Waltham Cllr. Patricia Simpson 41 Peaks Lane, New Waltham Cllr. Rosemary Thompson 2 Martin Way, New Waltham Cllr. Joanne Welham 6 Greenlands Avenue, New Waltham Cllr. Anne Baxter 18 Sophia Avenue, Scartho Ward Councillors Cllr. John Fenty Tel. 07712 398656 Cllr. Steve Harness Tel. 07925 050706 Cllr. Stan Shreeve Tel. 07702 343340 MP Martin Vickers Tel. 01472 602325 for an appointment Martin holds a surgery at Waltham Library the second Saturday of each month 11:30 - 13:30 Parish Clerk Mrs Kathy Peers Tel. 01472 280290 Email: [email protected] Closing Dates for inclusion of items in Newsletter The newsletter is published quarterly in February, May, August and November. The closing date for the receipt of articles and advertisements is the 15th of the month preceding the publication. The closing date for our November newsletter is 14th October 2017 Please send articles, news and advertisements to the Parish Clerk at [email protected] New Waltham Parish Council, working together to improve our community 2 Notes from the Chairman These quarterly newsletters seem to come Details of how to book are via email: around very quickly, either that or I am [email protected] getting old. -

Unlocking Local Leadership on Climate Change: Perspectives from Coalition Mps

Unlocking local leadership on climate change: perspectives from coalition MPs “ Some of the areas of “ Localism is powerful… “ A key test of this greatest potential will be these opportunities are government’s climate those where delivery is being ambitiously pursued change policy should be local, supported by a with a focus on green the extent to which it makes common national businesses and the most of the potential framework.” investments.” that localism offers.” Damian Hinds MP Martin Vickers MP Julian Huppert MP Unlocking local leadership on climate change: © Green Alliance 2012 perspectives from coalition MPs Green Alliance’s work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No derivative works 3.0 unported Published by Green Alliance, June 2012 licence. This does not replace copyright but gives certain rights ISBN 978-1-905869-65-7 without having to ask Green £5 Alliance for permission. Designed by Howdy and printed by Park Lane Press Under this licence, our work may be shared freely. This provides the Edited by Hannah Kyrke-Smith, Faye Scott and Rebecca Willis. freedom to copy, distribute and transmit this work on to others, This publication is a product of Green Alliance’s Climate provided Green Alliance is credited Leadership Programme under the Political Leadership theme. as the author and text is unaltered. This work must not be resold or www.green-alliance.org.uk/politicalleadership used for commercial purposes. These conditions can be waived The views of contributors are not necessarily those of Green under certain circumstances with Alliance. the written permission of Green Alliance. For more information about this licence go to http:// Green Alliance creativecommons.org/licenses/ Green Alliance is a charity and independent think tank focused on by-nc-nd/3.0/ ambitious leadership for the environment. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Tuesday Volume 604 5 January 2016 No. 91 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 5 January 2016 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2016 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON.DAVID CAMERON,MP,MAY 2015) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. David Cameron, MP FIRST SECRETARY OF STATE AND CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. George Osborne, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Michael Fallon, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. Michael Gove, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,INNOVATION AND SKILLS AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Iain Duncan Smith, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH—The Rt Hon. Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Nicky Morgan, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT—The Rt Hon. Justine Greening, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR TRANSPORT—The Rt Hon. -

Urgent Open Letter to Jesse Norman Mp on the Loan Charge

URGENT OPEN LETTER TO JESSE NORMAN MP ON THE LOAN CHARGE Dear Minister, We are writing an urgent letter to you in your new position as the Financial Secretary to the Treasury. On the 11th April at the conclusion of the Loan Charge Debate the House voted in favour of the motion. The Will of the House is clearly for an immediate suspension of the Loan Charge and an independent review of this legislation. Many Conservative MPs have criticised the Loan Charge as well as MPs from other parties. As you will be aware, there have been suicides of people affected by the Loan Charge. With the huge anxiety thousands of people are facing, we believe that a pause and a review is vital and the right and responsible thing to do. You must take notice of the huge weight of concern amongst MPs, including many in your own party. It was clear in the debate on the 4th and the 11th April, that the Loan Charge in its current form is not supported by a majority of MPs. We urge you, as the Rt Hon Cheryl Gillan MP said, to listen to and act upon the Will of the House. It is clear from their debate on 29th April that the House of Lords takes the same view. We urge you to announce a 6-month delay today to give peace of mind to thousands of people and their families and to allow for a proper review. Ross Thomson MP John Woodcock MP Rt Hon Sir Edward Davey MP Jonathan Edwards MP Ruth Cadbury MP Tulip Siddiq MP Baroness Kramer Nigel Evans MP Richard Harrington MP Rt Hon Sir Vince Cable MP Philip Davies MP Lady Sylvia Hermon MP Catherine West MP Rt Hon Dame Caroline