Northern Ireland Peace Monitoring Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Affairs

CCBS – LEGISLATIVE AFFAIRS 17/02/2015-25/02/2015 Committees Wednesday 18 February 2015 Committee for Finance and Personnel EU Funding Programmes: PEACE IV and INTERREG 5A - Briefing from DFP & Special EU Programmes Body (SEUPB) • Mr Frank Duffy, DFP – Head of EU Division • Mr Dominic McCullough, DFP – Head of North/South Policy and Programmes Unit • Mr Pat Colgan, Special EU Programmes Body – Chief Executive • Mr Shaun Henry, Special EU Programmes Body – Director of the Managing Authority Hansard: http://data.niassembly.gov.uk/HansardXml/committee-12149.pdf YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLXY24wt0YA Summary: At a briefing to the Committee for Finance and Personnel on ‘EU Funding Programmes: PEACE IV and INTERREG 5A’ from DFP & Special EU Programmes Body (SEUPB) focused on providing an update on the key areas of interest, including the Peace and INTERREG programmes, and on issues that were raised before in Committee, which are the administrative simplification of the new programme and the implementation of the existing programmes, from 2007 to 2013. Issues of note: Mr Frank Duffy (Department of Finance and Personnel): “At the previous Committee meeting in April, members raised concerns about the application process for the cross-border programmes, in particular work being undertaken to reduce the time taken for a decision on funding applications, and the perceived bureaucracy that went along with that. At the time, I identified that our aim was to reduce considerably the application process time, and I undertook to do so by at least one third. Therefore, to update the Committee on that, thanks to some very engaged and constructive discussions that DFP has had with DPER and SEUPB, we have reached agreement for a process to be 1 undertaken from start to finish in 36 weeks. -

"Third Way" Republicanism in the Formation of the Irish Republic Kenneth Lee Shonk, Jr

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects "Irish Blood, English Heart": Gender, Modernity, and "Third Way" Republicanism in the Formation of the Irish Republic Kenneth Lee Shonk, Jr. Marquette University Recommended Citation Shonk, Jr., Kenneth Lee, ""Irish Blood, English Heart": Gender, Modernity, and "Third Way" Republicanism in the Formation of the Irish Republic" (2010). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 53. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/53 “IRISH BLOOD, ENGLISH HEART”: GENDER, MODERNITY, AND “THIRD-WAY” REPUBLICANISM IN THE FORMATION OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC By Kenneth L. Shonk, Jr., B.A., M.A., M.A.T. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2010 ABSTRACT “IRISH BLOOD, ENGLISH HEART”: GENDER, MODERNITY, AND “THIRD-WAY” REPUBLICANISM IN THE FORMATION OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC Kenneth L. Shonk, Jr., B.A., M.A., M.A.T. Marquette University, 2010 Led by noted Irish statesman Eamon de Valera, a cadre of former members of the militaristic republican organization Sinn Féin split to form Fianna Fáil with the intent to reconstitute Irish republicanism so as to fit within the democratic frameworks of the Irish Free State. Beginning with its formation in 1926, up through the passage of a republican constitution in 1937 that was recognized by Great Britain the following year, Fianna Fáil had successfully rescued the seemingly moribund republican movement from complete marginalization. Using gendered language to forge a nexus between primordial cultural nationalism and modernity, Fianna Fáil’s nationalist project was tantamount to efforts anti- hegemonic as well as hegemonic. -

UK-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement

House of Commons International Trade Committee UK-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement Second Report of Session 2019–21 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 18 November 2020 HC 914 Published on 19 November 2020 by authority of the House of Commons The International Trade Committee The International Trade Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for International Trade and its associated public bodies. Current membership Angus Brendan MacNeil MP (Scottish National Party, Na h-Eileanan an Iar) (Chair) Mark Garnier MP (Conservative, Wyre Forest) Paul Girvan MP (DUP, South Antrim) Sir Mark Hendrick MP (Labour, Preston) Anthony Mangnall MP (Conservative, Totnes) Mark Menzies MP (Conservative, Fylde) Taiwo Owatemi MP (Labour, Coventry North West) Lloyd Russell-Moyle MP (Labour, Brighton, Kemptown) Martin Vickers MP (Conservative, Cleethorpes) Mick Whitley MP (Labour, Birkenhead) Craig Williams MP (Conservative, Montgomeryshire) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2020. This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright-parliament/. Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/tradecom and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the inquiry publications page of the Committee’s website. -

The Irish Left Over 50 Years

& Workers’ Liberty SolFor siociadl ownershaip of the branks aind intdustry y No 485 7 November 2018 50p/£1 The DEMAND EVERY Irish left over 50 LABOUR MP years VOTES AGAINST See pages 6-8 The May government and its Brexit process are bracing themselves to take the coming weeks at a run, trying to hurtle us all over a rickety bridge. Yet it looks like they could be saved by some Labour MPs voting for the To - ries’ Brexit formula. More page 5 NUS set to gut BREXIT democracy Maisie Sanders reports on financial troubles at NUS and how the left should respond. See page 3 “Fake news” within the left Cathy Nugent calls for the left to defend democracy and oppose smears. See page 10 Join Labour! Why Labour is losing Jews See page 4 2 NEWS More online at www.workersliberty.org Push Labour to “remain and reform” May will say that is still the ulti - trade deals is now for the birds. mate objective, but for not for years Britain will not be legally able to in - to come. troduce any new deals until the fu - The second option, which is often ture long-term treaty relationship John Palmer talked to equated with “hard” Brexit, is no with the EU has been negotiated, at deal. That is a theoretical possibil - the end of a tunnel which looks Solidarity ity. But I don’t think in practice cap - longer and longer. ital in Britain or elsewhere in The job of the left, the supporters S: You’ve talked about a Europe has any interest in that, and of the Corbyn leadership of the “Schrödinger’s Brexit”.. -

Committee for Finance Meeting Minutes of Proceedings 27 January

COMMITTEE FOR FINANCE MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS WEDNESDAY, 27 JANUARY 2021 Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings, Belfast Present: Dr Steve Aiken OBE MLA (Chairperson) Mr Paul Frew MLA (Deputy Chairperson) Mr Jim Allister MLA Mr Matthew O’Toole MLA Mr Jim Wells MLA Present by Video-conference: Mr Pat Catney MLA Ms Jemma Dolan MLA Mr Philip McGuigan MLA Mr Maolíosa McHugh MLA Apologies: None In Attendance: Mr Peter McCallion (Assembly Clerk) Mr Phil Pateman (Assistant Assembly Clerk) Mr Neil Sedgewick (Clerical Supervisor) Ms Heather Graham (Clerical Officer) The meeting commenced at 2:01pm in public session. The Chairperson conveyed the Committee’s deepest sympathy to Mr McHugh following the recent death of his mother Mr McHugh expressed his thanks to Members for their kind consideration. 1. Apologies There were no apologies. No notices were received from any Member of a delegation of their vote to another Member as per Temporary Standing Order 115(6). 1 2. Declaration of Interests There were no declarations of interest. Agreed: The Committee agreed that the Chairperson would write to the Chairperson’s Liaison Group and the Northern Ireland Assembly Commission to express concerns in respect of difficulties arising from the use of the Assembly’s video-conferencing facility which can sometimes adversely affect Members’ participation in committee meetings. 3. Draft Minutes The Committee considered the minutes of the meeting held on Wednesday, 20 January 2021. Agreed: The Committee agreed the minutes of the meeting held on Wednesday, 20 January 2021. Mr Frew joined the meeting at 2:04pm. 4. Matters Arising There were no matters arising. -

2012 Biennial Conference Layout 1

Biennial Delegate Conference | 2012 City Hotel, Derry 17th‐18th April 2012 Membership of the Northern Ireland Committee 2010‐12 Membership Chairperson Ms A Hall‐Callaghan UTU Vice‐Chairperson Ms P Dooley UNISON Members K Smyth INTO* E McCann Derry Trades Council** Ms P Dooley UNISON J Pollock UNITE L Huston CWU M Langhammer ATL B Lawn PCS E Coy GMB E McGlone UNITE Ms P McKeown UNISON K McKinney SIPTU Ms M Morgan NIPSA S Searson NASUWT K Smyth USDAW T Trainor UNITE G Hanna IBOA B Campfield NIPSA Ex‐Officio J O’Connor President ICTU (July 09 to 2011) E McGlone President ICTU (July 11 to 2013) D Begg General Secretary ICTU P Bunting Asst. General Secretary *From February 2012, K Smyth was substituted by G Murphy **From March 2011 Mr McCann was substituted, by Mr L Gallagher. Attendance At Meetings At the time of preparing this report 20 meetings were held during the 2010‐12 period. The following is the attendance record of the NIC members: L Huston 14 K McKinney 13 B Campfield 18 M Langhammer 14 M Morgan 17 E McCann 7 L Gallagher 6 S Searson 18 P Dooley 17 B Lawn 16 Kieran Smyth 19 J Pollock 14 E McGlone 17 T Trainor 17 A Hall‐Callaghan 17 P McKeown 16 Kevin Smyth 15 G Murphy 2 G Hanna 13 E Coy 13 3 Thompsons are proud to work with trade unions and have worked to promote social justice since 1921. For more information about Thompsons please call 028 9089 0400 or visit www.thompsonsmcclure.com Regulated by the Law Society of Northern Ireland March for the Alternative image © Rod Leon Contents Contents SECTION TITLE PAGE A INTRODUCTION 7 B CONFERENCE RESOLUTIONS 11 C TRADE UNION ORGANISATION 15 D TRADE UNION EDUCATION, TRAINING 29 AND LIFELONG LEARNING E POLITICAL & ECONOMIC REPORT 35 F MIGRANT WORKERS 91 G EQUALITY & HUMAN RIGHTS 101 H INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS & EMPLOYMENT RIGHTS 125 I HEALTH AND SAFETY 139 APPENDIX TITLE PAGE 1 List of Submissions 143 5 Who we Are • OCN NI is the leading credit based Awarding Organisation in Northern Ireland, providing learning accreditation in Northern Ireland since 1995. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Committee for Education Meeting Minutes of Proceedings 9

Northern Ireland Assembly COMMITTEE FOR EDUCATION Minutes of Proceedings WEDNESDAY 9 DECEMBER 2020 Video Conference and Room 30, Parliament Buildings, Belfast Present: Mr Chris Lyttle MLA (Chairperson) Ms Karen Mullan MLA (Deputy Chairperson) Ms Nicola Brogan MLA Mr Daniel McCrossan MLA Mr Robin Newton MBE MLA Present by Video Conference: Mr Maurice Bradley MLA Mr Robbie Butler MLA Mr William Humphrey MLA Mr Justin McNulty MLA Apologies: None In Attendance: Mr Peter McCallion (Assembly Clerk) Mr Mark McQuade (Assistant Clerk) Ms Paula Best (Clerical Supervisor) Ms Emma Magee (Clerical Officer) The meeting commenced at 9:35am in open session. 1. Apologies There were no apologies. 2. Chairperson’s Business 2.1 Cancellation of Scottish Highers The Chairperson advised Members that the Scottish Government had announced that owing to disruption to the provision of education in schools, there would be no Advanced or Higher end of year examinations in Scotland in 2021 and that grades would be awarded based on teacher judgements. Members recorded their concerns in respect of the absence of examination clarity in Northern Ireland. Some Members argued that GCSEs and A-levels should be cancelled in 2021 owing to disruption to the delivery of the curriculum caused by the pandemic. 2.2 Trends in International Maths and Science Study (TIMMS) The Chairperson advised Members that he and the Deputy Chairperson had met informally with Department of Education officials on 8 December 2020 in order to review the headline findings for Northern Ireland of the Trends in International Maths and Science Study 2019. The Committee recorded its congratulations to primary schools on the consistently positive results for mathematics at Primary 6. -

The Stationery Office Monthly Catalogue March 2013 Ii

The Stationery Office monthly catalogue March 2013 ii The publications in this catalogue are available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, telephone and fax & email TSO PO Box 29, Norwich NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Orders through the Parliamentary Hotline Lo-call 0845 7 023474 Fax orders: 0870 600 553 Email: [email protected] Textphone: 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other accredited agents House of Lords papers - Session 2012-13 1 PARLIAMENTARY PUBLICATIONS House of Lords papers - Session 2005-06 Unnumb- Titles and tables of contents for the sessional papers of the House of Lords 2005-06. - ca. 100p.: ered 30 cm. - 978-0-10-855010-2 £14.50 House of Lords papers - Session 2012-13 115 The work of the Joint Committee on the National Security Strategy in 2012: second report of session 2012-13: report, together with formal minutes. - Joint Committee on the National Security Strategy - Margaret Beckett (chair). - House of Commons papers 2012-13 984. - [2], 6p.: 30 cm. - 978-0-10-855037-9 £3.50 120 The Rookery South (Resource Recovery Facility) Order 2011: first special report of session 2012-13: report with evidence. - Joint Committee on the Rookery South (Resource Recovery Facility) Order 2011 - Brian Binley (chairman). - House of Commons papers 2012-13 991. - 14p.: 30 cm. - 978-0-10-855038-6 £5.00 123 28th report of session 2012-13: Rights of Passengers in Bus and Coach Transport (Exemptions) Regulations 2013; Jobseeker’s Allowance (Scheme for Assisting Persons to Obtain Employment) Regulations 2013: also includes information paragraphs on 5 instruments. -

Terrorist Speech and the Future of Free Expression

TERRORIST SPEECH AND THE FUTURE OF FREE EXPRESSION Laura K. Donohue* Introduction.......................................................................................... 234 I. State as Sovereign in Relation to Terrorist Speech ...................... 239 A. Persuasive Speech ............................................................ 239 1. Sedition and Incitement in the American Context ..... 239 a. Life Before Brandenburg................................. 240 b. Brandenburg and Beyond................................ 248 2. United Kingdom: Offences Against the State and Public Order ....................................................................... 250 a. Treason............................................................. 251 b. Unlawful Assembly ......................................... 254 c. Sedition ............................................................ 262 d. Monuments and Flags...................................... 268 B. Knowledge-Based Speech ................................................ 271 1. Prior Restraint in the American Context .................... 272 a. Invention Secrecy Act...................................... 274 b. Atomic Energy Act .......................................... 279 c. Information Relating to Explosives and Weapons of Mass Destruction............................................ 280 2. Strictures in the United Kingdom............................... 287 a. Informal Restrictions........................................ 287 b. Formal Strictures: The Export Control Act ..... 292 II. State in -

Committee for Justice Minutes of Proceedings Thursday

COMMITTEE FOR JUSTICE MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS THURSDAY 18 FEBRUARY 2021 Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings, Belfast Present: Mr Paul Givan MLA (Chairperson) Ms Linda Dillon MLA (Deputy Chairperson) Mr Doug Beattie MLA* Ms Sinéad Bradley MLA* Mr Gordon Dunne MLA* Mr Paul Frew MLA Ms Emma Rogan MLA* Ms Rachel Woods MLA* * These Members attended the meeting via video conferencing. Apologies: Ms Jemma Dolan MLA In Attendance: Mrs Christine Darrah (Assembly Clerk) Mrs Kathy O’Hanlon (Senior Assistant Clerk) Mrs Allison Mealey (Clerical Supervisor) The meeting commenced at 2.09 p.m. in closed session. 1. SL1: Amendment to the Criminal Justice (Sentencing) (Licence Conditions) (Northern Ireland) Rules 2009 Department of Justice officials joined the meeting at 2.11 p.m. The officials outlined the key points in relation to the policy intent behind the proposed Statutory Rule. The oral evidence was followed by a question and answer session. The officials agreed to provide further information on a number of issues. The Chairperson thanked the officials for their attendance. The Committee moved into open session at 3.17 pm. Agreed: The Committee agreed that the oral evidence session on the Stocktake of Policing Oversight and Accountability should be reported by Hansard. 2. Apologies As above. The Clerk informed the Committee that, under Standing Order 115(6), Jemma Dolan MLA had delegated authority to the Deputy Chairperson, Linda Dillon MLA, to vote on her behalf. 3. Draft Minutes Agreed: The Committee agreed the minutes of the meeting held on 11 February 2021. 4. Matters Arising Item 1 – Committee Forward Work Programme - February and March 2021 The Committee noted the Forward Work Programme for February and March 2021. -

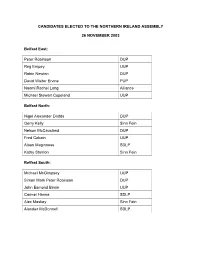

Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP

CANDIDATES ELECTED TO THE NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY 26 NOVEMBER 2003 Belfast East: Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP Belfast North: Nigel Alexander Dodds DUP Gerry Kelly Sinn Fein Nelson McCausland DUP Fred Cobain UUP Alban Maginness SDLP Kathy Stanton Sinn Fein Belfast South: Michael McGimpsey UUP Simon Mark Peter Robinson DUP John Esmond Birnie UUP Carmel Hanna SDLP Alex Maskey Sinn Fein Alasdair McDonnell SDLP Belfast West: Gerry Adams Sinn Fein Alex Atwood SDLP Bairbre de Brún Sinn Fein Fra McCann Sinn Fein Michael Ferguson Sinn Fein Diane Dodds DUP East Antrim: Roy Beggs UUP Sammy Wilson DUP Ken Robinson UUP Sean Neeson Alliance David William Hilditch DUP Thomas George Dawson DUP East Londonderry: Gregory Campbell DUP David McClarty UUP Francis Brolly Sinn Fein George Robinson DUP Norman Hillis UUP John Dallat SDLP Fermanagh and South Tyrone: Thomas Beatty (Tom) Elliott UUP Arlene Isobel Foster DUP* Tommy Gallagher SDLP Michelle Gildernew Sinn Fein Maurice Morrow DUP Hugh Thomas O’Reilly Sinn Fein * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from 15 January 2004 Foyle: John Mark Durkan SDLP William Hay DUP Mitchel McLaughlin Sinn Fein Mary Bradley SDLP Pat Ramsey SDLP Mary Nelis Sinn Fein Lagan Valley: Jeffrey Mark Donaldson DUP* Edwin Cecil Poots DUP Billy Bell UUP Seamus Anthony Close Alliance Patricia Lewsley SDLP Norah Jeanette Beare DUP* * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from