Reproductive Prints – the Address the Bailey Collection Includes a Very

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FACE to FACE Gallery News Issue No

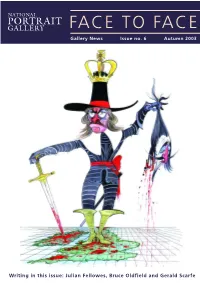

P FACE TO FACE Gallery News Issue no. 6 Autumn 2003 Writing in this issue: Julian Fellowes, Bruce Oldfield and Gerald Scarfe FROM THE DIRECTOR The autumn exhibition Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits offers an unusual opportunity to see fascinating images of those who usually remain invisible. The exhibition offers intriguing stories of the particular individuals at the centre of great houses, colleges or business institutions and reveals the admiration and affection that caused the commissioning of a portrait or photograph. We are also celebrating the completion of the new scheme for Trafalgar Square with the young people’s education project and exhibition, Circling the Square, which features photographs that record the moments when the Square has acted as a touchstone in history – politicians, activists, philosophers and film stars have all been photographed in the Square. Photographic portraits also feature in the DJs display in the Bookshop Gallery, the Terry O’Neill display in the Balcony Gallery and the Schweppes Photographic Portrait Prize launched in November in the Porter Gallery. Gerald Scarfe’s rather particular view of the men and women selected for the Portrait Gallery is published at the end of September. Heroes & Villains, is a light hearted and occasionally outrageous view of those who have made history, from Elizabeth I and Oliver Cromwell to Delia Smith and George Best. The Gallery is very grateful for the support of all of its Patrons and Members – please do encourage others to become Members and enjoy an association with us, or consider becoming a Patron, giving significant extra help to the Gallery’s work and joining a special circle of supporters. -

Darnley Portraits

DARNLEY FINE ART DARNLEY FINE ART PresentingPresenting anan Exhibition of of Portraits for Sale Portraits for Sale EXHIBITING A SELECTION OF PORTRAITS FOR SALE DATING FROM THE MID 16TH TO EARLY 19TH CENTURY On view for sale at 18 Milner Street CHELSEA, London, SW3 2PU tel: +44 (0) 1932 976206 www.darnleyfineart.com 3 4 CONTENTS Artist Title English School, (Mid 16th C.) Captain John Hyfield English School (Late 16th C.) A Merchant English School, (Early 17th C.) A Melancholic Gentleman English School, (Early 17th C.) A Lady Wearing a Garland of Roses Continental School, (Early 17th C.) A Gentleman with a Crossbow Winder Flemish School, (Early 17th C.) A Boy in a Black Tunic Gilbert Jackson A Girl Cornelius Johnson A Gentleman in a Slashed Black Doublet English School, (Mid 17th C.) A Naval Officer Mary Beale A Gentleman Circle of Mary Beale, Late 17th C.) A Gentleman Continental School, (Early 19th C.) Self-Portrait Circle of Gerard van Honthorst, (Mid 17th C.) A Gentleman in Armour Circle of Pieter Harmensz Verelst, (Late 17th C.) A Young Man Hendrick van Somer St. Jerome Jacob Huysmans A Lady by a Fountain After Sir Peter Paul Rubens, (Late 17th C.) Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel After Sir Peter Lely, (Late 17th C.) The Duke and Duchess of York After Hans Holbein the Younger, (Early 17th to Mid 18th C.) William Warham Follower of Sir Godfrey Kneller, (Early 18th C.) Head of a Gentleman English School, (Mid 18th C.) Self-Portrait Circle of Hycinthe Rigaud, (Early 18th C.) A Gentleman in a Fur Hat Arthur Pond A Gentleman in a Blue Coat -

Annual Review 2011 – 2012

AnnuA l Review 2011 – 2012 Dulwich Picture Gallery was established more than 200 years ago because its founders believed as many people as possible should see great paintings. Today we believe the same, because we know that art can change lives. I w hat makes us world-class is our exceptional collection of Old Master paintings. I england – which allows visitors to experience those paintings in an intimate, welcoming setting. I w hat makes us relevant is the way we unite our past with our present, using innovative exhibitions, authoritative scholarship and pioneering education programmes to change lives for the better. Cover image: installation view of David Hockney, Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, 1970-71, acrylic on canvas, 213 x 304. Tate, Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1971 © David Hockeny / Tate. Dulwich Picture Gallery is built on history. Picture Our From our founders’ wish to have an art Future: The Campaign for Dulwich Picture recognises a number of things of which gallery ‘for the inspection of the public’, Gallery has begun. Alongside my co-chair artists and scholars, aristocrats and school of the Campaign Cabinet, Bernard Hunter, particularly to celebrate our long-time children have come by horse, train, car we look forward to working with all of the Trustee and supporter Theresa Sackler, and bicycle to view our collection – Van Gallery’s supporters to reach this goal. who was recently awarded a DBE Gogh walked from Central London to view in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List, the Gallery in 1873. The paintings and The position we start from is a strong adding even more lustre to the Prince of building are a monument to the tastes of one: against the background of a troubled Wales’ Medal for Philanthropy which was two centuries ago, yet it is a testament world-economy, the Gallery exceeded its awarded to her in 2011. -

Preservation Board

The Preservation of Richmond Park © n 1751, the rangership was granted to King George’s youngest agricultural improvements. Minister Lord John Russell (later Earl Russell) in 1846. which still bears his name. Queen Elizabeth - the army’s famous daughter Princess Amelia. She immediately began to tighten the When a new gate and gate lodge In 1835 when Petersham Lodge Queen Mother) were “Phantom” restrictions on entry. Within 6 weeks of her taking up the post there were required for the Richmond In 1801 King George III decided that Henry Addington, his new Prime came on the market, the Office given White Lodge as reconnaissance Iwas an incident. Gate, the plan by Sir John Soane of Woods and Works purchased their first home after squadron, and (surviving in the Soane Museum in the estate, demolished the very their marriage in 1923. 50 acres in the The annual beating of the bounds of Richmond parish had always London) was submitted to the King decayed house, and restored the They found it too remote south-west required entry into the Park. But the bound-beating party of 1751 in April 1795 and was then marked whole of “Petersham Park” to and rapidly gave it up to of the Park found the usual ladder-stile removed. They entered by a breach in the “as approved by His Majesty”. Richmond Park. A new terrace move into London! were used for wall. Sir John Soane was also walk was made along the top of a large hutted instrumental in transforming the the hillside. Old Lodge had been By then the Park was camp for the “mole catcher’s cottage” into the demolished in 1839-41. -

812Carolinaarts-Pg44

vate collections to highlight the Queen’s accom- contradictions. This exhibition presents a major plishments as a devoted mother, a notable patron survey of Dial’s work, an epic gathering of over of the arts, and a loyal consort to the King. Royal fifty large-scale paintings, sculptures, and wall NC Institutional Galleries portraits by Allan Ramsay, Sir Joshua Reynolds, assemblages that address the most compelling continued from Page 43 and Sir William Beechey are featured in the exhi- issues of our time. Ongoing - The Mint Museum bition, as are representative examples of works Uptown will house the world renowned collec- a Charlotte resident and native of Switzerland fill the Gantt Center galleries with objects as from the English manufactories - Wedgwood, tions of the Mint Museum of Craft + Design, as who assembled and inherited a collection of diverse as the typewriter Alex Haley used when Chelsea, Worcester, and others - patronized by well as the American Art and Contemporary Art more than 1,400 artworks created by major he penned his Pulitzer Prize-winning book the Queen. Williamson Gallery, Through Dec. collections and selected works from the Euro- figures of 20th-century modernism and donated "Roots" to Prince’s guitar! Ongoing - Featur- 31 - Threads of Identity: Contemporary Maya pean Art collection. The building also includes it to the public trust. The Bechtler collection ing selections from the John & Vivian Hewitt Textiles. Maya peoples of Guatemala and south- a café, a Family Gallery, painting and ceramics comprises artworks by seminal figures such as Collection of African-American Art, one of the eastern Mexico are renowned for their time-hon- studios, classrooms, a 240-seat auditorium, a Alberto Giacometti, Joan Miro, Jean Tinguely, nation's most important and comprehensive ored tradition of magnificent attire. -

Your Guide to the Art Collection

ART AND ACADEMIA YOUR GUIDE TO THE ART COLLECTION Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh EH14 4AS 0131 449 5111 www.hw.ac.uk AG1107 CONTEMPORARYFind out more SCOTTISH ART FURTHER READING Heriot-Watt University would like to thank the Patrick N. O’Farrell: Heriot-Watt University: artists, their relatives and estates for permission An Illustrated History to include their artworks. Pearson Education Ltd, 2004 Produced by Press and Public Relations, Heriot-Watt University: A Place To Discover. Heriot-Watt University Your Guide To The Campus Heriot-Watt University, 2006 Printed by Linney Print Duncan Macmillan: Scottish Art 1460-2000 Photography: Simon Hollington, Douglas McBride Mainstream, 2000 and Juliet Wood Duncan Macmillan Copywriter: Duncan Macmillan Scottish Art in the Twentieth Century Mainstream, 1994 © Heriot-Watt University 2007 THE ART COLLECTION 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION A highlight of the collection is a group of very fine INTRODUCTION 1 Heriot-Watt University’s art collection reflects paintings by artists associated with the College of SIR ROBIN PHILIPSON 2 its history and the people who have shaped its Art, a good many of them first as student and then development over two centuries. Heriot-Watt as teacher. Many of these pictures were bought JOHN HOUSTON 4 University has a long-standing relationship with by Principal Tom Johnston and gifted by him to the DAVID MICHIE 6 the visual arts. One of the several elements brought University. The collection continues to grow, however. ELIZABETH BLACKADDER 8 together to create Edinburgh College of Art in 1907 Three portraits by Raeburn of members of the was the art teaching of what was then Heriot-Watt Gibson-Craig family and a magnificent portrait DAVID McCLURE 10 College. -

Royal Portraits and Sporting Pictures

ROYAL PORTRAITS AND SPORTING PICTURES FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF THEIR EXCELLENCIES THE GOVERNOR GENERAL AND LADY NORRIE AUCKLAND C TY ART GAL :RY ROYAL PORTRAITS AND SPORTING PICTURES FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF THEIR EXCELLENCIES THE GOVERNOR GENERAL AND LADY NORRIE AUCKLAND CITY ART GALLERY during the FESTIVAL OF THE ARTS 1955 HIS is ONE OF THE RARE OCCASIONS when the general public > is given the opportunity or seeing a well chosen and well > balanced private collection or valuable pictures, which in the ' ordinary course of things would not be seen outside an English country house. So what a great pleasure, as well as a privilege, it is for us in Auckland to be allowed to see this selection of royal portraits and sporting pictures from the collections of Their Excellencies the Governor- General and Lady Norrie. A private collection should reflect its owner; and that is exactly what the collection now being exhibited does. Even if we knew nothing previously of the special interests of Their Excellencies, we would be aware immediately from these works, of Their Excellencies' deep love of British history and those activities of country life which have played such an important part in forming the character of rural England. The paintings which form part of these collections demonstrate also the artistic judgment and taste of Their Excellencies, for all of them have been chosen not only for the personages and events represented, but for their qualities as works of art as well. Their Excellencies' pictures have not been exhibited previously in New Zealand, and Auckland feels proud that the exhibition should form part of its 1955 Festival of the Arts, which has already become a dominant feature in the life of our City. -

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN Revolutionary Times 1780-1810

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN Revolutionary Times 1780-1810 This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • Our sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN 1. The History of the Tate 2. From Absolute Monarch to Civil War, 1540-1650 3. From Commonwealth to the Georgians, 1650-1730 4. The Georgians, 1730-1780 5. Revolutionary Times, 1780-1810 6. Regency to Victorian, 1810-1840 7. William Blake 8. J. M. W. Turner 9. John Constable 10. The Pre-Raphaelites, 1840-1860 West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

Works of Art in the Stranger's Dining Room

Works of Art in the Stranger’s Dining Room Stranger’s Dining Room The room was originally a Peers’ Committee Room which was changed to a dining room in around 1 2 3 1867. By 1902 it had become the Entrance Irish Member’s Dining room, by 1914 Member’s Smoking Room and at some point between 1914 and 1938 it had become the Stranger’s Dining Room. In 2006 the dining room was 9 refurbished, wallpaper and carpet to A W N Pugin’s designs were reinstated, having been replaced over the years with incorrect designs. River Tests were also made on the plainly 4 Thames painted ceiling and original stencil patterns were discovered beneath, a rose and floral pattern in coral and green designed by Pugin and applied 8 by J G Crace and Son. The room is called Stranger’s Dining room as ‘Stranger’s’ was the term originally used to describe Entrance anyone who was not a Member of 7 6 5 Parliament, and this was one of the few rooms where MPs could bring guests to eat. Sir William Williams of Nantanog Charles Abbot 1st Baron Colchester 1634-1700 Speaker 1757-1829 Speaker 1802-17 Oil painting, attributed to Emma Williams Oil painting, by John Hoppner WOA 2680 WOA L30 (Loaned by the National Portrait Gallery, London) Chevening Chequers Oil painting, by Marcus May 2006 Oil painting, by Marcus May 2005 WOA 6504 WOA 6432 William Pitt 1759-1806 Prime Minister William Lenthall 1591-1662 Speaker Oil painting, after original by John Hoppner Oil painting, by Cornelius Johnson WOA 647 WOA 2741 Arthur Wellesley Peel, 1st Viscount Sir John Freeman-Mitford, Peel (1829-1912), Speaker of the Speaker 1801-2 House of Commons Oil painting, by Martin Archer Shee Oil painting, by William Ewart Lockhart WOA 2706 WOA 6550 Sir Fletcher Norton, Speaker 1770-80 Oil painting, by William Beechey WOA 2705 1. -

Frederick William Beechey (1796-1856)

332 Frederick William Beechey (1796- 1856) Portrait of Frederick William Beechey, by George Beechey; used with perrnis- sion of The Hakluyt Society Frederick William B.eechey, named after his godfather his brother Henry W. Beechey to conduct an overland William IV, was born in London on 17 February 17%, the survey of the northern coast of Africa. Duringthis service second son theof eminent portrait artistSir William Beechey, he was promotedto the rank of commander. Atthe end of R.A. He served both the Royal Navy and geographical the voyage he seems to have been unemployed, perhaps science withdistinction, authored books on arctic discov- for reasons of health after his physical exertions in the ery, and at the time of his death, 29 November 1856, was Arctic and in the desert country of Barca and Syrt. His Vice President of the Royal Society and President of the next appointment wasto the sloop Blossom on 12 January Royal GeographicalSociety. 1825. Beechey went to sea in 1806 at the early age of ten, The Blossom’s object was to meet with Franklin’s sec- attaining midshipman’sraqk the following year. After nearly ond overland expedition. She reached Kotzebue, via the twelve years of active service, he began his career as Pacific, on22 July 1826, and arrived at Chamisso Island on arctic voyager and geographer. In 18 18 he joined the Trent, the 25th. Beechey was only fivedays late for his intended a hired brig commanded by John Franklin, which was rendezvous with Franklin. A general reconnaissance of ordered to accompany H.M.S. -

Drawing After the Antique at the British Museum

Drawing after the Antique at the British Museum Supplementary Materials: Biographies of Students Admitted to Draw in the Townley Gallery, British Museum, with Facsimiles of the Gallery Register Pages (1809 – 1817) Essay by Martin Myrone Contents Facsimile TranscriptionBOE#JPHSBQIJFT • Page 1 • Page 2 • Page 3 • Page 4 • Page 5 • Page 6 • Page 7 Sources and Abbreviations • Manuscript Sources • Abbreviations for Online Resources • Further Online Resources • Abbreviations for Printed Sources • Further Printed Sources 1 of 120 Jan. 14 Mr Ralph Irvine, no.8 Gt. Howland St. [recommended by] Mr Planta/ 6 months This is probably intended for the Scottish landscape painter Hugh Irvine (1782– 1829), who exhibited from 8 Howland Street in 1809. “This young gentleman, at an early period of life, manifested a strong inclination for the study of art, and for several years his application has been unremitting. For some time he was a pupil of Mr Reinagle of London, whose merit as an artist is well known; and he has long been a close student in landscape afer Nature” (Thom, History of Aberdeen, 1: 198). He was the third son of Alexander Irvine, 18th laird of Drum, Aberdeenshire (1754–1844), and his wife Jean (Forbes; d.1786). His uncle was the artist and art dealer James Irvine (1757–1831). Alexander Irvine had four sons and a daughter; Alexander (b.1777), Charles (b.1780), Hugh, Francis, and daughter Christian. There is no record of a Ralph Irvine among the Irvines of Drum (Wimberley, Short Account), nor was there a Royal Academy student or exhibiting or listed artist of this name, so this was surely a clerical error or misunderstanding. -

Oklahoma City Museum of Art Provenance of Select Works of Art in the Permanent Collection

Oklahoma City Museum of Art Provenance of Select Works of Art in the Permanent Collection Bryn Critz Schockmel Kress/AAMD Fellow for Provenance Research August 21, 2020 key ; semi-colon direct transfer between owners . period possible gap in ownership history ( ) parenthesis auction sale [ ] brackets life dates of owner or footnote number Works of art are listed in alphabetical order by artist’s last name. All entries are written in chronological order, starting with the earliest known owner and ending with the Oklahoma City Museum of Art. Complete bibliographic entries for resources referenced in footnotes can be found at the end of this document. All entries are accurate, to the best of our knowledge, as of August 21, 2020. This document shall be updated as new material becomes known. Heinrich Aldegrever German, 1502-ca. 1561 Hercules and Antaeus, 1550 Engraving Gift of Charles Tilghman, 2008.015 Craddock and Barnard, London; purchased by Charles C. Tilghman [1921-2013], Oklahoma City, 1950s or 1960s [1]; given to Oklahoma City Museum of Art, December 23, 2007. [1] Oklahoma City Museum of Art Accession Checklist, May 7, 2008 2 Henry Alken British, 1785-1851 Whippet Hound, 1824 Oil on wood panel Gift of Margôt and Charles Nesbitt, 1976.034 Margôt [b. 1927] and Charles [1921-2007] Nesbitt, Oklahoma City, by April 1976 [1]; given to Oklahoma Museum of Art, September 15, 1976; transferred to Oklahoma City Art Museum, 1989; transferred to Oklahoma City Museum of Art, 2002. [1] Appraisal by the Colonial Art Company, dated April 5, 1976 3 Albrecht Altdorfer German, ca. 1480-1538 Mucius Scaevola Burning his Hand, ca.