Design Collaboration Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

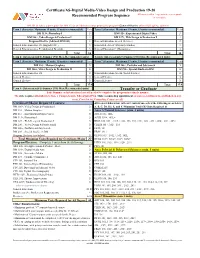

Digital Media-Video Design and Production 19-20 Recommended Program Sequence All Courses with a + Sign Indicate a Pre-Requisite Or Co-Requisite

Certificate/AS-Digital Media-Video Design and Production 19-20 Recommended Program Sequence All courses with a + sign indicate a pre-requisite or co-requisite DM 101 & Lab is a prerequiste for DM 115 & an Advisory course prior to the program (General Elective-offered fall, spring, summer) Term 1 (Semester: Maximum 19 units, 15 units recommended) Units Term 5 (Semester: Maximum 19 units, 15 units recommended) Units DM 113+, Photoshop I 3 DM 112+, Experimental Digital Video 3 DM 106+, Video Design & Production I 3 DM 127+, Web Design & Production I 3 Program Elective (Advised: DM 101) 3 General Education Area A (Science) 3 General Education Area D1 (English 101+) 3 General Ed. Area F (Diversity Studies) 3 General Education Area E (Additional Breadth) 3 General Education C (Humanities) 3 Total 15 Total 15 Term 2: (Intersession(6/3)-Summer (9/6) Max./Recommended units) Term 6: (Intersession(6/3)-Summer (9/6) Max./Recommended units) Term 3 (Semester: Maximum 19 units, 15 units recommended) Units Term 7 (Semester: Maximum 19 units, 15 units recommended) Units DM 110+, Motion Graphics 3 DM 246+, Portfolio and Job Search 3 DM 206+, Video Design & Production II 3 DM 298+, Special Studies in DM 3 General Education Area D2 3 General Education Area B (Social Science) 3 General Elective 3 General Elective 3 General Elective 3 General Elective 3 Total 15.0 Total 15.0 Term 4: (Intersession(6/3)-Summer (9/6) Max./Recommended units) Transfer or Graduate Take Summer or Intersession classes if needed to complete the program in a timely manner. -

CHECKLIST for the MINOR in NEW MEDIA and DIGITAL DESIGN 6 TOTAL COURSES

CHECKLIST for THE MINOR IN NEW MEDIA AND DIGITAL DESIGN 6 TOTAL COURSES CORE COURSES (MUST TAKE BOTH COURSES): _____ NMDD 1001: EXPLORATIONS IN DIGITAL DESIGN ______CISC 2500: INFORMATION AND DATA MANAGEMENT COURSEWORK: MUST TAKE 4 COURSES (THESE MAY BE IN A SINGLE CONCENTRATION, OR IN ANY COMBINATION FROM ACROSS CONCENTRATIONS) THE FOLLOWING COURSES COUNT IN ALL CONCENTRATIONS: ______CISC 2530: Computer GraphiCs ______CMBU 4471: The Business of New Media ______DTEM 3476: SoCial Media ______DTEM 2421: Digital ProduCtion for New Media ______NMDD 3880: Designing Smart Cities (ServiCe Learning Course) ______VART 2003: GraphiC Design and Digital Tools ______VART 2400: Fundamentals of Web Design A. New Media and Information ______DTEM 1401: IntroduCtion to Digital TeChnology and Emerging Media ______CISC 2350: Information and Web Programming ______CISC 2530: Digital Video and Multimedia ______CISC 2850: Computer and Data Analysis or INSY 4431: Web AnalytiCs ______CISC 3850: Information Retrieval Systems ______CISC 4001: Computers and Robots in Film (ICC) ______DTEM 1402: Digital Cultures ______DTEM 2417: Data Visualization ______DTEM: 3463: CiviC Media ______DTEM 2427: Digital Audio ProduCtion ______FITV 2621: Digital Video Design ______COMC 3340: Freedom of Expression ______COMC 3380 International CommuniCation (Globalism) ______COMC 3374: Media EffeCts ______COMC3350 or BLBU 4451: New Media and CommuniCation Law ______DTEM 2775: Writing for Online Media ______INSY 4431: Web AnalytiCs or CISC 2850: Computer and Data Analysis ______INSY 3442: -

A Study on Development and Current Application of Motion Graphic in Taiwan’S Popular Music

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences ISSN 2454-5899 Chen & Chang, 2019 Volume 5 Issue 1, pp. 124-134 Date of Publication: 23rd March 2019 DOI-https://dx.doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2019.51.124134 This paper can be cited as: Chen, C. M., & Chang. Y. J., (2019). A Study on Development and Current Application of Motion Graphic in Taiwan’s Popular Music. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 5(1), 124-134. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. A STUDY ON DEVELOPMENT AND CURRENT APPLICATION OF MOTION GRAPHIC IN TAIWAN’S POPULAR MUSIC Chia Min Chen Department of Graphic Arts and Communications, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan [email protected] Yen Jung Chang Department of Graphic Arts and Communications, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan [email protected] Abstract With the advances in technology, the way of communications has become more diverse. Motion graphic combines graphic design, animation design, and film languages. Motion graphic is a new industry with intense performance styles and can be used in different media and platforms, such as commercials, music videos, film and television titles, web pages, and various display screen sizes, etc. Because motion graphic is a non-narrative time-based media, mostly it combines with music. The Taiwan 25th Golden Melody Awards introduced motion graphic design for the first time in 2014. -

Application to Use Progressive Design-Build Project Review Committee Meeting: January 28, 2021 AGENDA

Application to Use Progressive Design-Build Project Review Committee Meeting: January 28, 2021 AGENDA 1. West Sound Technical Skill Center Overview 2. Project Team & Management 3. Project Scope 4. Budget and Funding 5. Procurement Approach and Schedule 6. Schedule 7. Design Build Suitability 8. Questions WEST SOUND TECHNICAL SKILLS CENTER PROJECT TEAM PROJECT MANAGEMENT Bremerton SD /Central Kitsap Capital/ OAC / Legal Team DB Procurement: 1% 2% 5% 15% 40% 5% 10% 20% 1% Design: 1% 2% 1% 20% 75% 1% 1% 5% 1% Construction / Closeout: 1% 2% 1% 15% 90% 1% 1% 5% 1% Wallace Leavell (Legal, DB) (Legal, Sydney Thiel Sydney Aaron Aaron Stacy Shewell Stacy Dan ChandlerDan Shani Watkins Shani Steve Murakami Steve Garth Steedman Garth Graehm Item Description Shoemaker Robin Design-Build Procurement/Contracting x x x x x x x x x Project Management x x x PMP / Project Controls / Workflow Processes x x x x Schedule Review and Analysis x x x x Cost Review and Analysis x x x x FF&E Coordination x x Warranty Period x x PROJECT SCOPE PROJECT SCOPE • Cosmetology ACADEMIC PROGRAMS • Criminal Justice • Culinary Arts • Dental • Digital Animation & Video Design • Esthetics • Professional Medical Careers • Automotive Technology ACADEMIC PROGRAMS • Collision Repair • Diesel Technology • Fire Safety • Manufacturing Maritime • Multi-Craft Construction Trades • Welding BUDGET & FUNDING Funding Scenario #1 Gross SF Budget Request Single funding allocation for the entire project in 21/23 Biennium 121,695 gsf $82,658,000 Funding Scenario #2 Gross SF Budget Request Phase -

LISA D. BURKE Fashion/Costume and Puppet Designer , Costumer

LISA D. BURKE Fashion/Costume and Puppet Designer , Costumer 11225 Morrison St., Apt.115, North Hollywood, CA 91601 Phone (Home): (818) 506-1352, (cell): (267) 971-4979 Email: [email protected] Website: http://web.mac.com/lburke3 QUALIFICATIONS Experienced in costume design/wardrobe styling, on set costumer, puppet designing,, foam sculpting and fabrication, flocking, sewing, crafts, puppet building, budgeting, wardrobe, and fitting costumes for Film, Television, and Theatrical productions. Also experienced in costume construction including draping, and flat pattern drafting. Skilled at making 3D forms using sculpting techniques and woodworking tools. Special skills include make-up, floral design, and trained in 3D and 2D CG programs, Maya, Render Man, Adobe Photoshop, Vectorworks, Lectra system, etc. EMPLOYMENT *Technical costume/puppet experience, portfolio, and references available upon request. GENERAL Roma, Los Angeles, CA. Designer and Pattern Maker for women’s fashion and costume line. 2009-present American Intercontinental University, Los Angeles, CA. Adjunct faculty for various costume design/pattern making classes 2007/08/09 in the Fashion/Costume Department. Cinema Secrets, Los Angeles, CA. Draper, First Samples Pattern Maker, Head Costume Designer, for Women’s wear, 2008-2009 Men’s wear, Children’s wear and Dogs for Fashion Company specializing in Costumes, creates tech packs, costing, fitting, manages department. The LA Opera, Los Angeles, CA. Pattern Maker, Assistant Draper men’s wear, flat pattern drafting, body padding/sculpting, tailoring, fitting, in charge of crew and delegating assignments. 2007/2008 The Character Shop, Los Angeles, CA. On Set Puppet Technician, Puppet Costume Construction for commercial work: 2006 Perdue Chickens, Foster Farms, Old Navy Moe’s Flower’s, Los Angeles, CA. -

Performing Arts Audio/Video Production Coordinator

Classification Title: Performing Arts Audio/Video Production Coordinator Department: Performing Arts EEO6 Code: 5 Employee Group: Classified Salary Grade: 25 Supervision Received From: Manager, Performing Arts Production Date of Origin: 9/2016 Supervision Given: Direction and Guidance Last Revision: 9/2016 Class specifications are intended to present a descriptive list of the range of duties performed by employees in the class. Specifications are not intended to reflect all duties performed by individual positions. JOB SUMMARY. Independently coordinates and provides highly technical audio and video services to the Performing Arts Department for dance, music and theater productions; works with technical theater students to supplement classroom and lab studies. DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS. The Performing Arts Audio/Video Production Coordinator is distinguished from Manager, Performing Arts Production by the former’s responsibility for providing audio and video services and for training students in the technical operations of the theater, while the incumbent in the latter class is responsible for planning, managing and coordinating all aspects of the District’s Performing Arts productions. ESSENTIAL AND MARGINAL FUNCTION STATEMENTS. Essential Functions: Essential responsibilities and duties may include, but are not limited to, the following: 1. Provides audio and video design and support for theater, dance and music productions as well as other performances and events of the Performing Arts Department; determines audio, video and recording needs for each production; investigates, diagnoses and resolves technical problems and malfunctions. 2. Designs, installs, sets up and operates a wide variety of audio-visual equipment, including multi-component sound systems, recording equipment, video equipment, special effects devices and projection sources to support productions and events. -

Applied Art and Design (AAD) 1

Applied Art and Design (AAD) 1 AAD 0053. Publication Design II APPLIED ART AND DESIGN Units: 3 Prerequisite: Completion of AAD 52, 54 or 62 with grade of "C" or better (AAD) Hours: 72 (36 lecture, 36 activity) Page layout for developing and producing high-quality multi-page AAD 0012. Visual Communication documents. Emphasis on publication design, production, typography, Units: 3 graphics, and pre-press. Includes research and application of effective Also known as COMM 12 magazine layout concepts, cover design, grid theory, graphics, text Hours: 54 lecture elements and printing standards and processes. (CSU) Study of visual communication including design principles, aesthetics, AAD 0054. Typography visual perception, non-verbal messages, relationship to verbal Units: 3 communication, audience analysis, mass media and persuasion. Prerequisite: Completion of AAD 52, 53, 61, 62, or 75 with grade of "C" or Historical overview of visual media as well as current trends and better technology. (C-ID JOUR 170) (CSU, UC) Advisory: Completion of AAD 60 with grade of "C" or better AAD 0020. Portfolio Development and Presentation Hours: 72 (36 lecture, 36 activity) Units: 3 A professional and historical approach to understanding typographic Advisory: Completion of AAD 70, 75, or 85 with grade of "C" or better principles and form, effects of type on the style and communication Hours: 72 (36 lecture, 36 activity) in print and screen. Includes study of historical and contemporary Function and use of the portfolio as a marketing device for artists and graphics and typographic design, conceptualizing, developing and designers. Styles, materials, resources in portfolio design. Evaluation of refining typographical forms, methods for analyzing typographic usage, professional goals and image building. -

Directory & Resource Guide

AIA Las Vegas 2020 Directory & Resource Guide Directory & Resource Guide Spring 2020 A Publication of AIA Las Vegas A Chapter of the American Institute of Architects AIA Las Vegas Table Of Contents 2020 Directory & Resource Guide A publication of AIA COMPONENTS AND RESOURCES AIA Las Vegas A Chapter of What is the AIA? 3 The American Institute of Architects AIA Structure 4 1131 S. Casino Center Blvd. Las Vegas, NV 89104 THE AIA WESTERN MOUNTAIN REGION Ph: 702-483-3838 www.aialasvegas.org WMR Components 5 AIA NEVADA & RESOURCE PAGES Publisher and 2020 AIA Nevada Executive Committee 6 Managing Editor: Nevada State Board of Architecture Interior Design and Randy Lavigne, Hon. AIA, Residential Design / NCARB 7 Executive Director Nevada Senators & Representatives 8 AIA Nevada / AIA Las Vegas [email protected] AIA LAS VEGAS 2020 Visionary, Platinum, Gold & Silver Sponsors 9 Layout and Editorial: 2020 AIA Las Vegas Board of Directors 10 Kelly Lavigne AIA LV Architecture Firm Profiles 12 AIA Nevada / AIA Las Vegas AIA LV Architecture Firms by Project Types 40 [email protected] AIA LV AIA Las Vegas Allied Firm Profiles 45 AIA LV Allied Firms by Product Types 68 AIA LV Membership (Architect, Associate, Emeritus and Allied) 71 © 2020 AIA Las Vegas. All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may not be reproduced by any means, in whole or in part without the prior written consent of the publisher. AIA Las Vegas What Is The AIA? 2020 Directory & Resource Guide The American Institute of Architects AIA is the professional association for architects and design professionals. When Mission Statement The American Institute of Architects is THE you see the designation “AIA” following the name of an architect, it means that he voice of the architecture profession or she is a fully licensed and registered architect who upholds the highest standards And THE resource for its members in service of ethics and professional practice. -

An Approach to Using Digital Technology in Scenic Design for Low Budget Performance

An Approach to using digital technology in scenic design for low budget performance. Name Simon Bowland ORCID identifier 0000-0002-8486-9090 Degree MR-FAPROD Master of Fine Arts FOR Code 190404 - Drama, Theatre and Performance Studies Submission December 2018 Faculty of Fine Arts and Music *This thesis is presented as partial fulfilment of the degree. Abstract This practice-based research is an exploration of current, accessible, digital technology and the impact it is having on visual-based scenic design for live performance. This is examined through my freelance art and design practice, which includes areas such as, props, sculpture, set design/construction and model making. This project considers visual-based digital technology in the process of creating scenic design solutions for low budget performance productions of less than $20,000.00 in total production costs (excluding personnel costs), taking typical profit share productions as the template. It focuses on accessible projection hardware and interactive visual software. Drawing from a range of digital based theorists and performance practitioners, I review the current use of digital technology in providing visual scenic design solutions for performance. This includes examples of recent productions that use visual based digital solutions in performance. Cost effective, accessible i options inspired by these examples are then investigated through my practice and discussed here. The staging of an exemplar low budget performance ‘Absolute Uncertainty’ (less than $12000 allocated costs, including in kind support and donations) is documented in the accompanying video file, located on the presented USB drive. This includes unedited video of a dress rehearsal (titled: Absolute Uncertainty 480p.m4v), and video samples of three rehearsals, two at the start of the rehearsal process (May 2017) and one toward the end of the rehearsal process (August 2017). -

Technology Education

TECHNOLOGY EDUCATION MEDIA ARTS Audio Video Design 1 Web Development 1 Game Development 1 Print Media 1 One Semester One Semester One Semester One Semester TEC 111/112 TEC 171/172 TEC 501/502 TEC 181/182 9-10-11-12 9-10-11-12 9-10-11-12 9-10-11-12 Audio Video Design 2 Web Development 2 Game Development 2 Print Media 2 One Semester One Semester One Semester One Semester TEC 121/122 TEC 281/282 TEC 511/512 TEC 251/252 9-10-11-12 9-10-11-12 9-10-11-12 9-10-11-12 Media Arts Design & Development* One Semester TEC 311/312 10-11-12 Prerequisite: Two of the following courses: Print Media 1, Game Development 1, Audio Video Design 1 and Web Development 1 and one of the following cours- es: Print Media 2, Game Development 2, Audio Video Design 2 and Web Development 2 or instructor approval. It is suggested that students get as much experience in a variety of Media Arts courses as possible before enrolling in Media Arts Design and Development. This course can be repeated for additional credit. ARCHITECTURE & ENGINEERING Residential Architecture PLTW Introduction to One Year Engineering Design One Year TEC 141/142 TEC 151/152 9-10-11-12 9-10-11-12 Commercial PLTW Civil Engineering & PLTW Principles of PLTW Digital Architecture Architecture (Honors) Engineering (Honors) Electronics (Honors) One Year One Year One Year One Year TEC 241/242 TEC 261/262 TEC 301/302 TEC 291/292 10-11-12 10-11-12 10-11-12 10-11-12 PLTW Engineering Design & Development (Honors)* One Year TEC 401/402 11-12 Prerequisite: Introduction to Engineering Design (IED) and Digital Electronics (DE) or Principles of Engineering (POE), although it is suggested that students take all three (IED, DE, and POE) prior to enrolling in Engineering Design & Date modified: 09/11/15 Development. -

Video IP Multicast IP Multicast Adaptive Bit Rate Architecture Technical Report OC-TR-IP-MULTI-ARCH-V01-141112

Video IP Multicast IP Multicast Adaptive Bit Rate Architecture Technical Report OC-TR-IP-MULTI-ARCH-V01-141112 RELEASED Notice This OpenCable™ technical report is the result of a cooperative effort undertaken at the direction of Cable Television Laboratories, Inc. for the benefit of the cable industry and its customers. You may download, copy, distribute, and reference the documents herein only for the purpose of developing products or services in accordance with such documents, and educational use. Except as granted by CableLabs in a separate written license agreement, no license is granted to modify the documents herein (except via the Engineering Change process), or to use, copy, modify or distribute the documents for any other purpose. This document may contain references to other documents not owned or controlled by CableLabs. Use and understanding of this document may require access to such other documents. Designing, manufacturing, distributing, using, selling, or servicing products, or providing services, based on this document may require intellectual property licenses from third parties for technology referenced in this document. To the extent this document contains or refers to documents of third parties, you agree to abide by the terms of any licenses associated with such third party documents, including open source licenses, if any. Cable Television Laboratories, Inc. 2014 OC-TR-IP-MULTI-ARCH-V01-141112 IP Multicast DISCLAIMER This document is furnished on an "AS IS" basis and neither CableLabs nor its members provides any representation or warranty, express or implied, regarding the accuracy, completeness, noninfringement, or fitness for a particular purpose of this document, or any document referenced herein. -

Structuring Theory and Practice for Motion Graphics in Spatial Contexts

Networking Knowledge 9(3) Make, Mistake, Journey Method through motion – structuring theory and practice for motion graphics in spatial contexts ARTHUR MARIA STEIJN, The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Design ABSTRACT Contemporary scenography often consists of video-projected motion graphics. The field is lacking in academic methods and rigour: descriptions and models relevant for the creation as well as in the analysis of existing works. In order to understand the phenomenon of motion graphics in a scenographic context, I have been conducting a practice-led research project. Central to the project is construction of a design model describing sets of procedures, concepts and terminology relevant for design and studies of motion graphics in spatial contexts. The focus of this paper is the role of model construction as a support to working systematically practice-led research project. The design model is being developed through design laboratories and workshops with students and professionals who provide feedback that lead to incremental improvements. Working with this model construction-as-method reveals aspects of the tension between theory and praxis. KEYWORDS Motion graphics, spatial, design model, theory, praxis 1. Introduction and background The experience of contemporary scenography increasingly includes elements that involve digital technologies. Digitally created or manipulated visual content that is video-projected on (or emitted from) screens contribute to the narrative and add to the drama of performances. These projections consist of images (either still images or images changing over time) that appear interconnected to the physical three-dimensional setting. I shall refer to images-changing-over-time as motion graphics.