Dr. Ron Shroyer: an Historical Study of His Career and Contributions to Central Methodist University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1-September 2, 2003

Communitas MVCC Faculty/Staff Newsletter September 2nd, 2003 Program Name A complete list of the Changes Fall 2003 Chemical Dependency Practitioner AAS (from Chem Dependency Counseling) Cultural Series Computer Aided Drafting AOS Events (from Drafting) can be found Culinary Arts Management AOS beginning on page 2 (from Food Service) Recreation & Leisure Services AAS (Recreation Leadership) President Michael Schafer’s Convocation Remarks Good Morning: Thanks to Jim Suriano and the Sodexho staff for putting on this wonderful breakfast. I am happy to welcome a few special guests who took the time out of their schedules to join us this morning: John Stetson- Chair, MVCC Board of Trustees David Mathis - Trustee Dana Higgins - Former member of the Board of Trustees Edward Stephenson –Oneida County Legislator MVCC Receives Mike Parsons- President of First Source and a member of our Foundation Board It is truly special to have the entire college community together today as we Donated Electric begin a new academic year. It’s really pretty quiet here throughout the summer. The cam- Vehicles pus finally comes alive when all of you return. There are a couple of unusual To the newest members of the College Community, let me extend a very warm new vehicles traveling around the Utica welcome and convey to you how pleased we are that you have chosen to become a part Campus this fall.They are two-passenger of MVCC. We hope that you will very quickly feel at home here, and please let us know open electric vehicles donated by the if there are any ways we can help. -

The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Not All Killed by John Wayne: The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk 1940s to the Present A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in American Indian Studies by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 © Copyright by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 ABSTRACT OF THESIS Not All Killed by John Wayne: Indigenous Rock ‘n’ Roll, Metal, and Punk History 1940s to the Present by Kristen Le Amber Martinez Master of Arts in American Indian Studies University of California Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Maylei Blackwell, Chair In looking at the contribution of Indigenous punk and hard rock bands, there has been a long history of punk that started in Northern Arizona, as well as a current diverse scene in the Southwest ranging from punk, ska, metal, doom, sludge, blues, and black metal. Diné, Apache, Hopi, Pueblo, Gila, Yaqui, and O’odham bands are currently creating vast punk and metal music scenes. In this thesis, I argue that Native punk is not just a cultural movement, but a form of survivance. Bands utilize punk and their stories as a conduit to counteract issues of victimhood as well as challenge imposed mechanisms of settler colonialism, racism, misogyny, homophobia, notions of being fixed in the past, as well as bringing awareness to genocide and missing and murdered Indigenous women. Through D.I.Y. and space making, bands are writing music which ii resonates with them, and are utilizing their own venues, promotions, zines, unique fashion, and lyrics to tell their stories. -

Rob’S Album of the Week: the Slackers

Rob’s Album Of The Week: The Slackers Ska is a genre that has been in a bit of a crossroads over the past few years. It’s kind of in the same position punk rock was in the late 2000s, out of the limelight but still around somewhat, and there’s a dedicated fan base still packing venues to dance to the rhythms. For 25 years The Slackers from New York City have been keeping two tone alive and they’re not going away. Furthering the latter is their brand new self-titled album coming out on February 19. Bringing that trademark jazzy spin on the genre, Vic Ruggiero and crew haven’t slowed down at all since coming up from Manhattan in 1991. The groovy sextet from The Big Apple incorporates a bit of psychedelia and garage rock in their latest release. Each track brings something different; a few are heavy with the horns while others have the keys as the base of the entire song. It definitely makes the experience a stimulating one. It’ll be difficult to grow bored while diving to this one. Ruggiero also brings that laid back soul he’s known for to keep everything timeless. Is Ska due for the 4th Wave? Only time will tell. It’ll take a bunch of kids rejuvenating the rude boy ideal and that’s only a small part of what it’ll take. A big part of this weekly review are my top tracks off of the Album Of The Week. Open wide, take a bite, repeat and get your fill. -

June 2019 New Releases

June 2019 New Releases what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 79 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 13 FEATURED RELEASES Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 44 YEASAYER - TOMMY JAMES - STIV - EROTIC RERUNS ALIVE NO COMPROMISE Non-Music Video NO REGRETS DVD & Blu-ray 49 Order Form 90 Deletions and Price Changes 85 800.888.0486 THE NEW YORK RIPPER - THE ANDROMEDA 24 HOUR PARTY PEOPLE 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 (3-DISC LIMITED STRAIN YEASAYER - DUKE ROBILLARD BAND - SLACKERS - www.MVDb2b.com EDITION) EROTIC RERUNS EAR WORMS PECULIAR MVD SUMMER: for the TIME of your LIFE! Let the Sunshine In! MVD adds to its Hall of Fame label roster of labels and welcomes TIME LIFE audio products to the fold! Check out their spread in this issue. The stellar packaging and presentation of our Lifetime’s Greatest Hits will have you Dancin’ in the Streets! Legendary artists past and present spotlight June releases, beginning with YEASAYER. Their sixth CD and LP EROTIC RERUNS, is a ‘danceable record that encourages the audience to think.’ Free your mind and your a** will follow! YEASAYER has toured extensively, appeared at the largest festivals and wowed those audiences with their blend of experimental, progressive and Worldbeat. WOODY GUTHRIE: ALL STAR TRIBUTE CONCERT 1970 is a DVD presentation of the rarely seen Hollywood Bowl benefit show honoring the folk legend. Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Odetta, son Arlo and more sing Woody home. Rock Royalty joins the hit-making machine that is TOMMY JAMES on ALIVE!, his first new CD release in a decade. -

By: Lydia Ascacíbar, 4ºA ROOTS

JAMAICAN MUSIC By: Lydia Ascacíbar, 4ºA ROOTS: The music of Jamaica includes Jamaican folk music and many popular genres of music such as ska, reggae, dub, mento, rocksteady, dancehall, reaggea fusion and related styles. The Jamaican musical culture is the result of the merger of U.S. elements (rhythm and blues, rock and roll, soul) African and nearby Caribbean islands such as Trinidad and Tobago (Calypso and soca). EL REGGAE: It is especially popular thanks to the internationally renowned artists such as Bob Marley. Jamaican music has had a major influence on other styles of different countries. In particular, the practice of ``toasting'' for Jamaican immigrants in NY which evolved into the origin of ``rap''. Are also influenced other genres: punk, jungle and rock lovers. SOME FACTS: It is a kind of spiritual music, whose lyrics predominates praise of God or Jah (often exclaims Rastafari meaning "Prince Tafari" (ras is prince in amaharico), which refers to the birth name, Ras Tafari Makonnen, Haile King Selassie I of Ethiopia (1892-1975), revered as a prophet by the Rastafarians. letters in Other recurring themes include poverty, resistance to government oppression and the praises of ganja or marijuana. Some consider that the roots reggae had its peak in the late 1970s.'s roots reggae is an important part of the Jamaican culture. Though other forms of reggae, dancehall and have replaced it in terms of popularity in Jamaica, Roots Reggae found a small but growing in the world. Instruments Why reggae? -Guitar -Mbiras Currently is generally called raggamuffin or ragga reggae substyles some. -

The Bands of Detroit

IT’S FREE! TAKE ONE! DETROIT PUNK ROCK SCENE REPORT It seems that the arsenal of democracy has been raided, pillaged, and ultimately, neglected. A city once teeming with nearly two million residents has seemingly emptied to 720,000 in half a century’s time (the actual number is likely around 770,000 residing citizens, including those who aren’t registered), leaving numerous plots of land vacant and unused. Unfortunately, those areas are seldom filled with proactive squatters or off-the-grid residents; most are not even occupied at all. The majority of the east and northwest sides of the city are examples of this urban blight. Detroit has lost its base of income in its taxpaying residents, simultaneously retaining an anchor of burdensome (whether it’s voluntary or not) poverty-stricken, government-dependent citizens. Just across the Detroit city borders are the gated communities of xenophobic suburban families, who turn their collective noses at all that does not beckon to their will and their wallet. Somewhere, in the narrow cracks between these two aforementioned sets of undesirables, is the single best punk rock scene you’ve heard nary a tale of, the one that everyone in the U.S. and abroad tends to overlook. Despite receiving regular touring acts (Subhumans, Terror, Common Enemy, Star Fucking Hipsters, Entombed, GBH, the Adicts, Millions of Dead Cops, Mouth Sewn Shut, DRI, DOA, etc), Detroit doesn’t seem to get any recognition for homegrown punk rock, even though we were the ones who got the ball rolling in the late 60s. Some of the city’s naysayers are little more than punk rock Glenn Becks or Charlie Sheens, while others have had genuinely bad experiences; however, if the world is willing to listen to what we as Detroiters have to say with an unbiased ear, we are willing to speak, candidly and coherently. -

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DEL PERÚ FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Formas De Organización De Las Escenas Musicales Altern

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DEL PERÚ FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Formas de organización de las escenas musicales alternas en Lima El caso de las bandas ska del bar de Bernabé Tesis para optar el Título de Licenciado en Antropología que presenta: César Camilo Riveros Vásquez 20 de Diciembre, 2012 ÍNDICE Introducción..................................................................................................................I Referencias a la antropología de la música.............................................................XVI 1. Referentes Históricos..............................................................................................1 1.1 Las tres olas del ska en el mundo.....................................................................1 1.2 La masificación de la escena subterránea en Lima........................................74 1.3 El ska en Lima...............................................................................................146 2 Dinámicas de sistemas complejos.........................................................................163 2.1 Conceptos fundamentales..............................................................................168 2.2 Organizaciones musicales como sistemas complejos auto organizados.......177 2.2.1 Primer nivel de interacción: Personas..................................................184 2.2.2 Segundo nivel de interacción: Bandas..................................................190 2.2.3 Tercer nivel de interacción: Colectivos, argollas y trabajo colectivo.....199 -

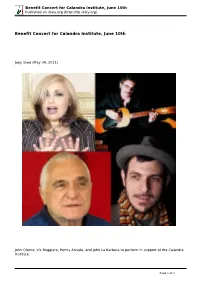

Benefit Concert for Calandra Institute, June 10Th Published on Iitaly.Org (

Benefit Concert for Calandra Institute, June 10th Published on iItaly.org (http://ftp.iitaly.org) Benefit Concert for Calandra Institute, June 10th Joey Skee (May 09, 2011) John Giorno, Vic Ruggiero, Penny Arcade, and John La Barbera to perform in support of the Calandra Institute. Page 1 of 3 Benefit Concert for Calandra Institute, June 10th Published on iItaly.org (http://ftp.iitaly.org) BENEFIT CONCERT Friday, June 10, 2011, 6 pm John D. Calandra Italian American Institute 25 West 43rd Street, 17th floor between 5th and 6th Avenues Please join us for an exciting evening of performances to benefit the Calandra Institute and its journal Italian American Review. Enjoy music and spoken word as presented by world- renowned artists John Giorno, Vic Ruggiero, Penny Arcade, and John La Barbera. Wine and refreshments will be served. The Calandra Institute is the only academic research institute in the country dedicated to the study of Italian-American history and culture. In the past five years, we have introduced ever more engaging scholarly and cultural programming for your appreciation. The more recent additions to our unique offerings include the newly relaunched journal Italian American Review, an annual three-day, international conference, the webcasts of Italics 2.0 and Nota Bene, and the upcoming exhibition “Migrating Towers: The Gigli of Nola and Beyond.” We have been able to do this and much more, providing it all free to you, the Calandra Institute's friends and colleagues. Tickets: $35 at the door or in advance. Cash or check made payable to "Friends of the Calandra Institute Foundation." (We do not accept credit cards.) If you are unable to attend the concert, the Calandra Institute is also accepting tax-deductible donations. -

Come Work for Us Call 410.455.1260

THE RETRIEVER WEEKLY November 1, 2005 17 Arts & Entertainment Welcome to the Church of Slack: The Slackers live JULIE SAGER Retriever Weekly Editorial Staff the main stage area and craned their necks eagerly as possible, keeping the energy high and the mood for any sign of the group. Rarely have I seen a strong. I have seen this band perhaps a dozen times New York City’s ska and reggae favorites The crowd at this type of show so very excited just to over the last fi ve years and have never seen a bad Slackers took the stage at the Ottobar last week in catch a glimpse of a band, but the long-absent or even mediocre set, though last summer things their fi rst Baltimore show in at least three years. Slackers had the audience positively addicted. began to get a bit weaker after the departure of With local openers Captain of Industry and the What makes the Slackers a completely the spastic but endearing co-frontman Q-Maxx. Rootworkers, the much-beloved band effortlessly fascinating group is the way they manage to But with the cool, almost beatnik presence of proved to the fans present that it was more than seamlessly combine a mellow reggae attitude bassist Marcus and the infamous “Disco Dave” worth the long wait to see them again. with the high-energy political consciousness of on sax, the band remains unbeatable. It was a set The Slackers have a special place in my heart early ska. Frontman Vic Ruggiero is like the Bob that left me grinning nonstop for the fi rst several as the fi rst band I ever saw live, fi ve years ago. -

“Doghouse Bass” Is the Eagerly Anticipated Third Studio Album by Traditional Ska / Reggae / Rocksteady Band INTENSIFIED, out on Grover Records

“Doghouse Bass” is the eagerly anticipated third studio album by traditional ska / reggae / rocksteady band INTENSIFIED, out on Grover Records. INTENSIFIED are guaranteed to get people dancing and raise the spirits of all around them. Playing authentic 60s style ska, rocksteady and reggae, the band’s good- time feel, obvious love of this music and confidence in its wide appeal has led to near legendary status. The quality of their songs and joy in playing them live has gained the band a large following and a reputation as one of the world’s finest of this genre. Three studio albums, an early compilation album and a live album, plus several 7” singles have received much critical acclaim in the music press, fanzine world, on the web and on radio stations across the globe. This in turn has meant a steady flow of gigging throughout Europe, with the band now a firm headline act. INTENSIFIED have been fortunate enough to share a stage with dozens of bands and singers, from Jools Holland to an authentic Zulu choir, including most of the contemporary ska favourites around the globe: Hepcat, The Slackers, The Toasters, Tokyo Ska Paradise Orchestra … 2 Tone stars such as The Selecter and Bad Manners … and original ska and reggae legends from the past and present including Prince Buster, Jimmy Cliff, Laurel Aitken, Desmond Dekker, Alton Ellis, Dennis Brown, Phylis Dillon, Morgan Heritage and the originators, Skatalites. The band has also had the pleasure of working on stage with Jamaican greats Rico, Dennis Alcapone and Dave Barker. The band remains standing defiant against a sea of pop, punk and other modern interpretations of original Jamaican sounds, not against progress or to put up musical limitations, but to continue sharing the pure, untampered and uplifting styles with the world. -

2016 Motif Music Award Winners

2016 Motif Music Award Winners Americana BEST ACT: Cactus Attack You take away the music, take away the late nights, take away the miles of road and the hangovers and you’re left with five close friends who have stood the test of time. Add all of the beers, butts and bastardized tunes back in to the equation and you get one hell of a band — Cactus Attack. This band has been running hard since 2008 and meshing their Swamp Yankee sound with their love of bluegrass and good old rock ‘n’ roll. They have two albums and one on the way. The band consists of Ryan “Stonewall” Jackson on guitar and vocals; Taylor “Bloodhound” Brennan on guitar, banjo and vocals; Derek “Pretty Boy” Pearson on guitar, banjo and vocals; Mike “Stovepipe” Walker on upright bass and vocals; and Chris “The Milkman” Hickman on percussion and vocals. They are 100 proof hell on wheels! For more, saguaro to cactus-attack.com or catch them out at The Parlour in Providence on Thursday, May 12. SINGER / SONGWRITER: Nate Cozzolino Nate Cozzolino is an emerging musical force whose latest project is collectively known as The Lost Arts. Since his arrival in Rhode Island from Japan, where he spent a decade honing his craft in the smoky cocktail lounges and perpetually open bars of the Japanese urban sprawl, Nate has rapidly embedded himself into the live music scene. Armed with a catalog of both original songs and re-imagined covers, Nate’s performances serve to tell the ongoing story of the highs and lows of a gypsy life very much examined. -

Shanty Town Jamaican Sounds

Share Report Abuse Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In INICIO DESCARGAS ACT UALIDAD AGENDA CONVOCAT ORIAS AUDIOVISUAL SELECT ER RECORDS L U N E S , 7 D E M A Y O D E 2 0 1 2 Granadians en el London International Ska SHANTY TOWN Festival Espacio, sin ánimo de lucro, dedicado a la difusión de la cultura musical jamaicana. Contacto: [email protected] Twitter: @Shant yTownBlog Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/shantytow n.jamaicansounds PDFmyURL.com Archivo del blog Archivo del blog ent radas 2 Tonians (1) Aba Shanti I (1) Aggrolites The (28) Aggrotones Los (5) Akatz (9) Al Barry and The Aces (1) Al Supersonic and The Teenagers (3) Alberto Tarin (1) All Rudies in Jail (1) Alpheus (5) Alton Ellis (20) Ansell Collins (1) B.B Seaton (1) Fotos de Laramie Shubber Baba Brooks (4) Publicado por Shanty Town en 08:33 0 comentarios Back in Band (1) Etiquetas: audiovisual, Granadians Bad Manners (4) Badalonians (3) PDFmyURL.com London International Ska Festival Bandits (6) Barnalites (4) BB Seaton (2) Beatdown The (7) Beginners The (1) Begoña Bang Matu (10) Ben Gunn Mento Band (3) Bite The (1) Bob Andy (1) Bob Marley (1) Briatore (1) Bullets The (5) Byron Lee and The Dragonaires The London International Ska Festival was in town over the (6) weekend, 3rd – 6 th May. For four days the O2 Academy in Islington Cabrians (8) was the only place to be to for those who love off- beat rhythms and Carlos Dingo (2) know how to skank. Caroloregians The (5) Back for its second year, the festival kicked off on Thursday with a headline show from Jamaican trio The Pioneers, and by all Cherry Boop The Soundmakers accounts seemed to be a good start to the festival.