Visual Trips the Psychedelic Poster Movement in San Francisco Visual Trips the Psychedelic Poster Movement in San Francisco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edition 1 | 2019-2020

2019 SSPA OFFICERS, DIRECTORS, TRUSTEES AND MEMBERS PRESIDENT DIRECTORS TRUSTEES Bruce T. Cameron Jason R. Cameron & MEMBERS Kurt DeVries * Roger Good VICE PRESIDENT John J. Hayes, III Kevin Leddy & CLERK N. Frank Neer Joy P. Schiffmann Richard L. Evans Meg Nelson Thomas D. Shipp Tina Watson TREASURER Brian S. Noble Susan Weisenfluh Robert C. Jordan, Jr. Jeffrey C. Pratt * Elizabeth A. Sullivan Rebecca J. Synnestvedt *Chairmen of Community Trust SOUTH SHORE MUSIC CIRCUS 3 CAPE COD MELODY TENT From The EXECUTIVE PRODUCER… Welcome It’s been almost 70 years of transformation in the live music and recording industries. Technology continues to advance at record speed and we appreciate you taking the time to slow down and smell the roses with us. Thank you for making your memories with us here at the Cape Cod Melody Tent and South Shore Music Circus. It’s because of your loyalty that we continue to do what we do. It is our pleasure to welcome back many performers who consider our venues more than just a stop on tour but a home away from home. They appreciate just as well as we do, the intimate concert setting experience our venues bring with our patrons. Artists like Lee Brice, Brett Eldredge, Chris Botti, and Jim Gaffigan are just a few of the many returning performers under the tents this summer. At the same time, the summer is a time to try new experiences and we invite you to do so by seeing our newcomers at the venue, artist like Brothers Osborne, Foreigner, and Squeeze. We’d like to thank our patrons for keeping their money where their heart is. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

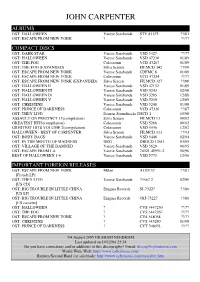

John Carpenter

JOHN CARPENTER ALBUMS OST: HALLOWEEN Varese Sarabande STV 81152 ??/81 OST: ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK ? ? ??/?? COMPACT DISCS OST: DARK STAR Varese Sarabande VSD 5327 ??/?? OST: HALLOWEEN Varese Sarabande VSD 47230 01/89 OST: THE FOG Colesseum VCD 47267 01/89 OST: THE FOG (EXPANDED) Silva Screen FILMCD 342 ??/00 OST: ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK Varese Sarabande CDFMC 8 01/89 OST: ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK Colesseum VCD 47224 ??/?? OST: ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK (EXPANDED) Silva Screen FILMCD 327 ??/00 OST: HALLOWEEN II Varese Sarabande VSD 47152 01/89 OST: HALLOWEEN III Varese Sarabande VSD 5243 02/90 OST: HALLOWEEN IV Varese Sarabande VSD 5205 12/88 OST: HALLOWEEN V Varese Sarabande VSD 5239 12/89 OST: CHRISTINE Varese Sarabande VSD 5240 01/90 OST: PRINCE OF DARKNESS Colesseum VCD 47310 ??/87 OST: THEY LIVE Demon Soundtracks DSCD 1 10/90 ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13(compilation) Silva Screen FILMCD 13 09/92 GREATEST HITS(compilation) Colesseum VSD 5266 09/92 GRESTEST HITS VOLUME 2(compilation) Colesseum VSD 5336 12/92 HALLOWEEN - BEST OF CARPENTER Silva Screen FILMCD 113 ??/93 OST: BODY BAGS Varese Sarabande VSD 5448 02/94 OST: IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS DRG DRGCD 12611 03/95 OST: VILLAGE OF THE DAMNED Varese Sarabande VSD 5629 06/95 OST: ESCAPE FROM LA Varese Sarabande 74321 40951-2 06/96 BEST OF HALLOWEEN 1-6 Varese Sarabande VSD 5773 12/96 IMPORTANT FOREIGN RELEASES OST: ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK Milan A120137 ??/81 [French LP] OST: THEY LIVE Varese Sarabande 73367.2 02/90 [US CD] OST: BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA Enigma Records SJ-73227 ??/86 [US LP] OST: BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA Enigma Records 4XJ-73227 ??/86 [US cassette] OST: HALLOWEEN ? CVS 3447230 ??/?? OST: THE FOG ? CVS 3447267 ??/?? OST: ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK ? CVS 348038 ??/?? OST: CHRISTINE ? CVS 345240 01/90 OST: PRINCE OF DARKNESS ? CVT 348031 ??/?? ©4 August 2005 GRAHAM NEEDHAM Last updated on 10/12/04 23:54 Do you have corrections and/or additions to this discography? Email: [email protected] World Wide Web: http://www.cybernoise.com/ Rarities/Second Hand for sale/trade: http://www.cybernoise.com/mocyber.htm . -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 22, 2016

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 22, 2016 NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORY EXCLUSIVE EAST COAST VENUE FOR BILL GRAHAM AND THE ROCK AND ROLL REVOLUTION The National Museum of American Jewish History (NMAJH) in Philadelphia will be the exclusive East Coast venue for Bill Graham and the Rock and Roll Revolution. The exhibition, which opens on September 16 and will run through January 16, 2017, presents the first comprehensive retrospective about the life and career of legendary rock impresario Bill Graham (1931–1991). Recognized as one of the most influential concert promoters in history, Graham played a pivotal role in the careers of iconic artists including the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Santana, Fleetwood Mac, the Who, Led Zeppelin, the Doors, and the Rolling Stones. He conceived of rock & roll as a powerful force for supporting humanitarian causes and was instrumental in the production of milestone benefit concerts such as Live Aid (1985)—which took place in Philadelphia and London—and Human Rights Now! (1988). The Museum will be open late on Wednesday nights (until 8 pm) throughout the run of the show.* Bill Graham lived the America Dream, and helped to promote and popularize a truly American phenomenon: Rock & Roll. The exhibition illuminates how his childhood experiences as a Jewish emigrant from Nazi Germany fueled his drive and ingenuity as a cultural innovator and advocate for social justice. Born in Berlin, Graham immigrated to New York at the age of ten as part of a Red Cross effort to help Jewish children fleeing the Nazis. He went to live with a foster family in the Bronx and spent his teenage years in New York City before being drafted to fight in the Korean War. -

Recreation Brochure

Saint Peter Community & Family Education City of Saint Peter Recreation & Leisure Services Department 2021 Fall BrochureSeptember–December 2021 Classes & Activities REGISTRATION BEGINS IMMEDIATELY! Community Education & Recreation & Leisure Classes & Activities Brochure, published three times a year. 2021 / Issue #3 Saint Peter Community Center Nonprofit Org. 600 South Fifth Street U.S. Postage PAID St. Peter, MN 56082 Permit No. 10 St. Peter, MN 56082 POSTAL PATRON St. Peter, MN 56082 Download the PDF to your desktop for page navigation and active email and web links! TABLE of CONTENTS Registration Information .............................................................. 2 MEA BREAK Community Education scholarship details ................................. 2 ACTIVITIES Teen Pantry / Children’s Weekend Food Program ..................... 2 All ages and families, no registration required. Saints Overtime (School Age Care) ...................................... 1 & 2 Wed., Oct. 20, Tori’s Precious Pets, Youth General Interest ............................................................... 2-4 1:30–2:30 p.m., Saint Peter Public Library Youth STEAM classes ....................................................................3 Thu., Oct. 21, Creation Station, 1:30–2:30 p.m., Saint Peter Public Library Youth Music Lessons ................................................................... 3 Youth Sports .................................................................................. 4 Fri., Oct. 22, Movie in the Park, Movie starts at 7 p.m., -

Conference Booklet

THE PROLONGED DEATH OF THE HIPPIE 1967–1969 12–14 SEPTEMBER 2019 CONFERENCE|MUSIC|POETRY WITH ED SANDERS ANNE WALDMAN AND MANY OTHERS 1 The poem of America has reached the time of my youthful rebellion the years of Civil Rights marches & what they used to call the “mimeograph revolution” with its stenciled magazines & manifestoes & the recognition of rock & roll & folk-rock as an art form […] Its consonants are the clicks of kisses in tipis & rapes in huts of fists in gloves & skins in rainbows of death more common than hamburger and life more plentiful than wheat of women more certain & men more willing to wake up thinking each day could be paradise & weeping or shrugging when it wasn’t […] And then comes the question of evil. It was hard for a person like myself […] to realize my Nation veers in & out of evil but evil is the only word for some of it From: Edward Sanders, America: A History in Verse, Vol. 3: 1962–1970 (2004). THURSDAY, 12 SEPTEMBER 11:00 –12:30 Intro (p. 8) Welcome Address (Philipp Schweighauser) Introduction (Christian Hänggi) Timeline 1967–1969 (Peter Price) 14:00–15:45 Panel: Music (p. 9) Chair: Christian Hänggi “A Short Time To Be There”: Life, Death, and The Grateful Dead (Andrew Shields) The Hippie and the Freak. Reflections on a Pop-Cultural and Sub-Cultural Difference in Regard of Frank Zappa’s Art (Alexander Kappe) Why Bob Dylan Did Not Sing in Woodstock And Why He Was No Hippie (But a Real Hipster) – The Re-Invention of Popular Music as a Medium of Poetry and Messianic Hope (Martin Schäfer) 16:00–17:30 Panel: Religion & Spirituality (p. -

October 11, 2015 Bill Graham and the Rock & Roll Revolution

May 7 - October 11, 2015 Bill Graham and the Rock & Roll Revolution Bill Graham played no musical instruments, save for the occasional cow bell. He could not really sing, and he never wrote a word of a single song performed on stage, and yet he changed rock music forever. During a crucial period of cultural transformation in American history, Bill Graham “stage managed” the rock revolution. His passion reflected the ideals of a generation and his life’s work has shaped musical taste and standards around the world to this day. Born Wolodia Grajonca in Berlin on January 8, 1931, Graham came to America as a Jewish refugee at the age of eleven with nothing to his name except the clothes on his back, a few photographs of his family, and a prayer book only to become the greatest impresario in the history of rock ‘n’ roll. Though he blocked the experiences of his early childhood from his memory, the hardship he endured left indelible marks on his character. He was strong and determined—and often abrasive. His quick temper was legendary, but equally unmistakable was his charisma and his compassion. It was one of America’s most turbulent eras. The Vietnam War was raging, the civil rights movement had progressed from non-violent to militant, and the airwaves carried messages of cultural revolution. Young people, the baby boom generation, had grown increasingly disillusioned with the world around them. Rejecting the stiff and stultifying values of the postwar era, they set out to remake the world by experimenting with new ways of living, new definitions of freedom, new philosophies, and a radical new style of music. -

Ramon Sender Oral History

Ramon Sender Oral History San Francisco Conservatory of Music Library & Archives San Francisco Conservatory of Music Library & Archives 50 Oak Street San Francisco, CA 94102 Interview conducted April 14, 16 and 21, 2014 Mary Clare Bryztwa and Tessa Updike, Interviewers San Francisco Conservatory of Music Library & Archives Oral History Project The Conservatory’s Oral History Project has the goal of seeking out and collecting memories of historical significance to the Conservatory through recorded interviews with members of the Conservatory's community, which will then be preserved, transcribed, and made available to the public. Among the narrators will be former administrators, faculty members, trustees, alumni, and family of former Conservatory luminaries. Through this diverse group, we will explore the growth and expansion of the Conservatory, including its departments, organization, finances and curriculum. We will capture personal memories before they are lost, fill in gaps in our understanding of the Conservatory's history, and will uncover how the Conservatory helped to shape San Francisco's musical culture throughout the past century. Ramon Sender Interview This interview was conducted at Ramon Sender’s home in San Francisco on April 14, 16 and 21, 2014 by Mary Clare Brzytwa and Tessa Updike. Mary Clare Brzytwa Mary Clare Brzytwa is Assistant Dean for Professional Development and Academic Technology at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. Specializing in electronic music with a background in classical flute and improvisation, she has played festivals internationally and at home including Festival des Musiques Innovatrices, Gilles Peterson’s World Wide Festival, La Siestes Electroniques Festival, Unlimited 21, and The San Francisco Electronic Music Festival. -

Escape Reality Through the Psychedelic Counterculture Movement

Escape reality through the psychedelic counterculture movement. Created by Shannen Hulley & Melissa Lager DES 185 | Winter Quarter 2017 Introduction i Exhibition Overview 1 Exhibition Brief 2 Lookbooks 3-5 Object List 6-19 Concept Plan & Massing Study 20-21 Floor Plan 22-23 Scale Model 24-27 Interviews 28-29 Exhibition Details 31 Renderings 32-36 Color Palette 37 Material Palette 38 Furniture 39 Paint Locations 40 Lighting 41 Exhibition Identity 43 Typology 44-46 Graphic Color Palette 47 Promotional Graphics 48-53 Merchandise 54-55 FAR OUT Manetti Shrem Museum of Art Shannen Hulley & Melissa Lager Introduction 16 March 2017 Far Out is an exhibit that curates escapism through various mediums from the counterculture movements that took place during the 60s and 70s Psychedelic era, including anti-society groups, music and art. Far Out aims to create a conversation among its visitors, asking them to question whether counterculture still exists today, with the inclusion of a collection of a 21st century re-emergence of transcendence through the arts. Far Out will be a safe space for people to gather, reflect, and communicate about the impact issues in society have on individuals and groups of people, all while considering the movements of the past. The psychedelic movement started in San Francisco, and quickly found its way to Davis as evident by the UC Davis Domes. Although the domes were established in 1972, they still exist today, keeping alive the spirit of escapism at the school, and making Far Out a relevant exhibit for the community. i 1 FAR OUT Manetti Shrem Museum of Art Exhibition Overview Shannen Hulley & Melissa Lager Exhibition Brief & Outline 16 March 2017 heme hiition utine A display of art created during and inspired by the late 1960s-70s Psychedelic and counterculture movements, including the extension aroun nformation of escapism into the 21st century through art. -

1 Survey-Dada

A&EMSURVEY.qxd 1/10/08 17:51 Page 4 Phaidon Press Limited Regent's Wharf All Saints Street London N1 9PA Phaidon Press Inc. ART AND ELECTRONIC 180 Varick Street New York, NY 10014 www.phaidon.com First published 2009 © 2009 Phaidon Press Limited All works © the artists or the estates of MEDIA the artists unless otherwise stated. ISBN: 0 7148 4782 8 A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of Phaidon Press. Designed by Hoop Design Printed in Hong Kong cover, Ben Rubin and Mark Hansen Listening Post 2001–03 inside flap, James Turrell Catso, Red, 1967, 1994 pages 2–3 Robert Rauschenberg with Billy Klüver Soundings 1968 page 4 Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik TV Bra 1975 back cover and spine, interior page, Tanaka Atsuko Electric Dress 1957 EDITED BY EDWARD A. SHANKEN A&EMSURVEY.qxd 1/10/08 17:51 Page 6 CHARGED ENVIRONMENTS page 96 PREFACE EDWARD A. DOCUMENTS page 190 WORKS page 54 LE CORBUSIER, Iannis XENAKIS, Edgard VARÈSE Philips Pavilion, 1958 page 97 Carolee SCHNEEMANN with E.A.T. Snows, 1967 page 98 John CAGE Imaginary Landscape No. 4 (1951), 1951 page 99 SHANKEN page 10 MOTION, DURATION, ILLUMINATION MOTION, DURATION, ILLUMINATION PULSA Boston Public Gardens Demonstration, 1968 page 100 Frank GILLETTE and Ira SCHNEIDER Wipe Cycle, 1968 page 100 page 55 Robert RAUSCHENBERG with Billy KLÜVER Soundings, 1968 page 100 László MOHOLY-NAGY Light-Space Modulator, 1923–30 page 55 page 193 Wolf VOSTELL and Peter SAAGE Electronic Dé-Coll/age Happening Room (Homage à Dürer), 1968 page 101 Naum GABO Kinetic Construction (Standing Wave), 1919–20 page 56 Ted VICTORIA Solar Audio Window Transmission, 1969–70 page 102 Thomas WILFRED Opus 161, 1965–6 page 57 Wen-Ying TSAI with Frank T. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 13, 2016 Media Contacts Yael Eytan 215.923.5978 / [email protected] 773.551.6956

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 13, 2016 Media Contacts Yael Eytan Jennifer Isakowitz 215.923.5978 / [email protected] 215.391.4666 / [email protected] 773.551.6956 (c) 703.203.1577 (c) THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORY PRESENTS BILL GRAHAM AND THE ROCK & ROLL REVOLUTION, ON VIEW SEPTEMBER 16, 2016 – JANUARY 16, 2017 The Museum is the Exclusive East Coast Venue for this Comprehensive Retrospective of the Life and Career of Rock Impresario Bill Graham The National Museum of American Jewish History (NMAJH) in Philadelphia is the exclusive East Coast venue for Bill Graham and the Rock & Roll Revolution. On view September 16, 2016 through January 16, 2017, the exhibition presents the first comprehensive retrospective about the life and career of legendary rock impresario Bill Graham (1931–1991). Recognized as one of the most influential concert promoters in history, Graham played a pivotal role in the careers of iconic artists including the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Santana, Fleetwood Mac, the Who, Led Zeppelin, the Doors, and the Rolling Stones. He conceived of rock & roll as a powerful force for supporting humanitarian causes and was instrumental in the production of milestone benefit concerts such as Live Aid (1985)—which took place in Philadelphia and London—and Human Rights Now! (1988). The Museum will be open late on Wednesday nights (until 8 pm) throughout the run of the show.* Bill Graham lived the American Dream, and helped to promote and popularize a truly American phenomenon: Rock & Roll. The exhibition illuminates how his childhood experiences as a Jewish emigrant from Nazi Germany fueled his drive and ingenuity as a cultural innovator and advocate for social justice. -

Science Fiction Cinema

Science Fiction Cinema One Day Course Tutor: Michael Parkes Science Fiction Cinema This course will examine how the science fiction genre has explored the relationship between humanity, technology and the other, to try to answer the question “what does it mean to be human?” The course will chart the history of the genre; from the early worlds of fantasy depicted in silent films, through to the invasion anxieties of the war years, the body politics of the 70s and 80s and the representation of technology in contemporary sci-fi cinema. The one day course will also examine how the genre is currently being rebranded for contemporary audiences and how fandom has been important to its success. The course will include lots of clips, resources for you to take away and the opportunity to discuss the important questions that science fiction cinema asks. What is Science Fiction? Most film genres are difficult to compartmentalise but there often tends to be one key convention that allows us to understand the nature of the film. Horror films are scary, Comedies make us laugh but Science Fiction appears to be a little more complicated and difficult to tie down. They can be about the future, but then again can be set in the past, they explore themes of identity, technology and the other but then again sometimes don’t! It has been a long standing struggle in Film Studies to really define what science fiction is; some believe it is a sub-genre of Horror whereas others believe it is a genre of its own merit.