Peoples' Social Movements: an Alternative Perspective on Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Jharkhand Movement: Regional Aspiration Has Fulfilled Yet

Indian J. Soc. & Pol. 06 (02):33-36 : 2019 ISSN: 2348-0084(P) ISSN: 2455-2127(O) HISTORY OF JHARKHAND MOVEMENT: REGIONAL ASPIRATION HAS FULFILLED YET AMIYA KUMAR SARKAR1 1Research Scholar, Department of Political Science, Adamas University Kolkata, West Bengal, INDIA ABSTRACT This paper attempts to analyze the creation of Jharkhand as a separate state through the long developmental struggle of tribal people and the condition of tribal‟s in the post Jharkhand periods. This paper also highlights the tribal movements against the unequal development and mismatch of Government policies and its poor implementations. It is true that when the Jharkhand Movement gaining ground these non-tribal groups too became part of the struggle. Thus, Jharkhandi came to be known as „the land of the destitute” comprising of all the deprived sections of Jharkhand society. Hence, development of Jharkhand means the development of the destitute of this region. In reality Jharkhand state is in the grip of the problems of low income, poor health and industrial growth. No qualitative change has been found in the condition of tribal people as the newly born state containing the Bihar legacy of its non-performance on the development front. KEYWORDS: Regionalism, State Reconstruction, Jharkhand Movement INTRODUCTION 1859, large scale transference of tribal land into the hands of the outsiders, the absentee landlords has taken place in the The term Jharkhand literally means the land of forest, entire Jharkhand region, especially in Chotanagpur hill area. geographically known as the Chhotanagpur Plateau; the region is often referred to as the Rurh of India. Jharkhand was earlier The main concern of East India Company and the a part of Bihar. -

Cbcs Curriculum of Ma History Programme

CBCS CURRICULUM OF M.A. HISTORY PROGRAMME SUBJECT CODE = HIS FOR POST GRADUATE COURSES UNDER RANCHI UNIVERSITY Implemented from Academic Session 2018-2020 PG: HISTORY CBCS CURRICULUM RANCHI UNIVERSITY Members of Board of Studies for CBCS Syllabus of PG History, Under Ranchi University, Ranchi. Session 2018-20 Onwards i PG: HISTORY CBCS CURRICULUM RANCHI UNIVERSITY Contents S.No. Page No. Members of Core Committee I Contents ii COURSE STUCTURE FOR POSTGRADUATE PROGRAMME 1 Distribution of 80 Credits 1 2 Course structure for M.A. in HISTORY 1 3 Semester wise Examination Structure for Mid Semester & End Semester 2 Examinations SEMESTER I 4 I FC-101 Compulsory Foundation Course (FC) 3 5 II. CC-102 Core Course –C 1 5 6 III. CC-103 Core Course –C 2 7 7 IV CC-104 Core Course –C 3 9 SEMESTER II 8 I CC-201 Core Course- C 4 11 9 II. CC-202 Core Course- C 5 13 10 III. CC-203 Core Course –C 6 15 11 IV CC-204 Core Course –C 7 17 SEMESTER III 12 I EC-301 Ability Enhancement Course (AE) 19 13 II. CC-302 Core Course –C 8 21 14 III. CC-303 Core Course- C 9 23 15 IV CC-304 Core Course –C 10 25 SEMESTER IV 16 I EC-401 Generic/Discipline Elective (GE/DC 1) 27 17 II. EC-402 Generic/Discipline Elective (GE/DC 2) 33 18 III. CC-403 Core Course –C 11 39 19 IV PR-404 Core Course (Project/ Dissertation) –C 12 41 ANNEXURE 20 Distribution of Credits for P.G. -

Ancient Indian History & Culture (AIH & C) CBCS – Syllabus of CORE/GE

Ancient Indian History & Culture (AIH & C) CBCS – Syllabus of CORE/GE/DSE Papers Dr Lal Kishor Mandal (H.O.D Deptt of AIH&C) A. N. COLLEAGE DUMKA , (JHARKHAND) Semester – 1 Early civilization and political History of Ancient India ( up to mauryam age ) (Marks- 80) Core paper paper – 1st Topics : - Sources of Ancient Indian History ( From pre history ti 650 AD) –1) History of Archacology in india from the 19th century till the present , Pre Historic culture in india . General features – Chaleolithic culture in india . General features - The origin of the Aryans . The vedic Age ( Political conditions) – Poltical condition of india during the 6th century BC persion and macedomian invasion causes nature & effect . Mauryan dynasty origin & caste chandragupta maurya , Ashoka dhamma responsibility in the decline of the maurya . Core paper paper 2nd ( Marks – 80) Ancient History of India ( Mauryam Age to 1200AD) Topics Poltical History from BC 200to AD 200, sunga indo Greeks ,saka , kushan satvahana kharvela , The Sangama Age - social poltical &economic condition , The gupta dynasty – origin sanmdra gupta , Chandra gupta – II , Shikandra gupta decline , The vakatakas . Suggested Readings 1.Poltical History of Ancient India – H. C. Roy 2 . History of south india (also to hindi) – N . K . SHASTRI 3 . Prachin Bharatiya &sanskriti - R . K. CHOUDHARY SEMESTER – 2 , Ancient History (Marks – 80) Core Paper Topics PAPER - 3 1 . Social & economics History of Ancient India ( UP TO A.D.650). Topics – Source varna , Ashram&purushartha , origin of caste , family position of women , marriage significances& forms Aim & ideals of education in Ancient india , educational contress , Taxila Nalanda & vikramshila , untouchatnlity , agriculture trade &commerce indo roman trade . -

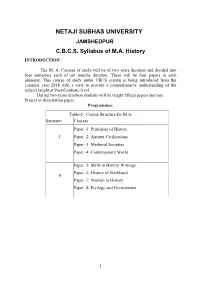

CBCS Syllabus of MA History

NETAJI SUBHAS UNIVERSITY JAMSHEDPUR C.B.C.S. Syllabus of M.A. History INTRODUCTION: The M. A. Courses of study will be of two years duration and divided into four semesters each of six months duration. There will be four papers in each semester. This course of study under CBCS system is being introduced from the calendar year 2018 with a view to provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject taught at Post-Graduate level. During two years duration students will be taught fifteen papers and one Project or dissertation paper. Programmes: Table-2 : Course Structure for M.A. Semester Courses Paper -1 Principles of History I Paper -2 Ancient Civilizations Paper -3 Medieval Societies Paper -4 Contemporary World Paper -5 Skills in History Writings Paper -6 History of Jharkhand II Paper -7 Women in History Paper -8 Ecology and Environment 1 Paper - 09 Socio Religious Movements in India III Paper - 10 Contemporary India (1947-2000) Paper – 11 Political Thought Paper – 12 Elective (Elect anyone from the following) Elective -01 Administrative History of Ancient India Elective -02 Administrative History of Medieval India Elective – 03 Administrative History of Modern India Paper – 13 Contemporary History of Jharkhand IV Paper – 14 History of Science and Technology Paper - 15 Elective (Elect anyone from the following) Elective -04 Socio-Economic History of Ancient India Elective -05 Socio-Economic History of Medieval India Elective -06 Socio-Economic History of Modern India Paper -- 16 Project 3 SYLLABUS OF M.A. HISTORY (AT A GLANCE) FIRST SEMESTER CORE PAPERS Course No. Course Name End Internal Written Total Semester Examination Paper - 1 Principles of History 70 30 100 Paper – 2 Ancient Civilizations 70 30 100 Paper - 3 Medieval Societies 70 30 100 Paper - 4 Contemporary World 70 30 100 4 SECOND SEMESTER CORE PAPERS Credit Course No. -

B.A. History Syllabus Click Here to Download

Prepared on the Guidelines of the U.G.C Courses of Study For Under Graduate Studies Department of History Under Choice Based Credit System (CBSE) To be implemented from Academic Session 2018-2019 Dr. Shyama Prasad Mukherjee University Morabadi, Ranchi, Jharkhand - 834009 1 CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction for B.A. Honours Course 03 2. Scheme for Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) in B.A. Honours 04-07 3. Core Papers (C) 08-31 4. Discipline Specific Elective (DSE) 32-44 5. Generic Elective (GE) 45-57 6. Skill Enhancement Course (SEC) 58-63 7. Scheme for Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) in B.A. (General and Pass Course) Program 64 8. Structure of B.A. (General and Pass Course) Programme, History as Discipline-1 under CBCS 65 9. Discipline Specific Course (DSE) 66-70 10. Discipline Specific Elective (DSE) 71-76 11.Generic Elective (GE)/Inter-Disciplinary 77-83 11. Ability Enhancement Elective Course (AEEC) 84-90 ___________ 2 INTRODUCTION The B.A. History Hones course will be of 3 years with 6 semesters in every 6 months under choice-based credit system (CBCS). There will be 14 papers (Core Course) in all. The students will offer 2 ability enhancement compulsory courses (AECC) in each first and second semester, 2 skill enhancement course (SEC) in each third and fourth semester. And 4 papers each from a list of discipline specific elective (DSE) in each fifth and sixth semester and generic elective papers (GE) in each first, second, third and fourth semester in each respectively. The examination will be taken for 80 marks for each paper in one sitting for 3 hrs at end of every semester. -

Acta Orientalia

“ ACTA ORIENTALIA EDIDERUNT SOCIETATES ORIENTALES DANICA FENNICA NORVEGIA SVECIA CURANTIBUS LEIF LITTRUP, HAVNIÆ HEIKKI PALVA, HELSINGIÆ ASKO PARPOLA, HELSINGIÆ TORBJÖRN LODÉN, HOLMIÆ SAPHINAZ AMAL NAGUIB, OSLO PER KVÆRNE, OSLO WOLFGANG-E. SCHARLIPP, HAVNIÆ REDIGENDA CURAVIT CLAUS PETER ZOLLER LXXIX Contents ARTICLES STEFAN BOJOWALD: Zu einigen Beispielen für den Wegfall von „H“ in der ägyptischen Sprache .................................................................. 1 STEFAN BOJOWALD: Zu den Schreibungen des ägyptischen Wortes „cwH.t“ „Ei“ .................................................................................... 15 ILIJA ČAŠULE: New Burushaski etymologies and the origin of the ethnonym Burúśo, Burúśaski, Brugaski and Miśáski ........................ 27 HONG LUO: Whence the Five Fingers? A philological investigation of Laghukālacakratantra 5.171‒173ab as quoted in sMan bla don grub’s Yid bzhin nor bu ...................................................................... 73 MICHAEL KNÜPPEL: Zwei Briefe Philipp Johann von Strahlenbergs an Curt Friedrich aus den Jahren 1723 und 1724 ............................ 111 RAJU KALIDOS: Caturviṃśati-Mūrti forms of Viṣṇu Additional notes on Daśāvatāra and Dvādaśa .................................................... 133 REVIEW ARTICLE CLAUS PETER ZOLLER: “Pagan Christmas: Winter feast of the Kalasha of the Hindu Kush” and the true frontiers of ‘Greater Peristan’ ...... 163 BOOK REVIEWS KNUTSON, JESSE ROSS. Into the twilight of Sanskrit Court Poetry. The Sena Salon of Bengal and Beyond, -

Sociology Name of Module: Tribal Movements in India

P a g e | 1 Module Detail and Its Structure Subject Name Sociology Paper Name Social Movements Module Title Tribal Movements in India Module Id SM 28 Pre-requisites Some knowledge of social movements and tribal social life Objectives To introduce the learners to some major tribal movements that occurred during British rule and after post independence in India and to draw lessons for readers also. Keywords Tribe, Alienation, Exploitation Development Team Role in Content Development Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Sujata Patel Dept. of Sociology, University of Hyderabad Paper Coordinator Prof. Biswajit Ghosh Professor, Department of Sociology, The University of Burdwan, West Bengal Email:[email protected] Content Writer Dr. Swapan Kumar Kolay Associate Professor and Head School of Anthropology & Tribal Studies Bastar University, Jagdalpur: 494001 Email: [email protected] Content Reviewer (CR) & Prof. Biswajit Ghosh Professor, Department of Sociology, The Language Editor (LE) University of Burdwan, West Bengal Email:[email protected] Name of Paper: Social Movements Sociology Name of Module: Tribal Movements in India P a g e | 2 Contents 1. Objectives ......................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Learning Outcomes .......................................................................................................................... -

Paper Download

Culture survival for the indigenous communities with reference to North Bengal, Rajbanshi people and Koch Bihar under the British East India Company rule (1757-1857) Culture survival for the indigenous communities (With Special Reference to the Sub-Himalayan Folk People of North Bengal including the Rajbanshis) Ashok Das Gupta, Anthropology, University of North Bengal, India Short Abstract: This paper will focus on the aspect of culture survival of the local/indigenous/folk/marginalized peoples in this era of global market economy. Long Abstract: Common people are often considered as pre-state primitive groups believing only in self- reliance, autonomy, transnationality, migration and ancient trade routes. They seldom form their ancient urbanism, own civilization and Great Traditions. Or they may remain stable on their simple life with fulfillment of psychobiological needs. They are often considered as serious threat to the state instead and ignored by the mainstream. They also believe on identities, race and ethnicity, aboriginality, city state, nation state, microstate and republican confederacies. They could bear both hidden and open perspectives. They say that they are the aboriginals. States were in compromise with big trade houses to counter these outsiders, isolate them, condemn them, assimilate them and integrate them. Bringing them from pre-state to pro-state is actually a huge task and you have do deal with their production system, social system and mental construct as well. And till then these people love their ethnic identities and are in favour of their cultural survival that provide them a virtual safeguard and never allow them to forget about nature- human-supernature relationship: in one phrase the way of living. -

History Hons

MODIFIED CBCS CURRICULUM OF HISRORY HONOURS PROGRAMME SUBJECT CODE = 07 FOR UNDER GRADUATE COURSES UNDER RANCHI UNIVERSITY Implemented from Academic Session 2017-2020 Members of Board of Studies of CBCS Under- Graduate Syllabus as per Guidelines of the Ranchi University, Ranchi. i HISTORY HONS. CBCS CURRICULUM RANCHI UNIVERSITY Contents S.No. Page No. Members of Core Committee i Contents ii -iii COURSE STUCTURE FOR UNDERGRADUATE ‘HONOURS’ PROGRAMME 1 Distribution of 140 Credits 1 2 Course structure for B.A..(Hons. Programme) 1 3 Subject Combinations allowed for B. A. Hons. Programme 2 4 Semester wise Examination Structure for Mid Sem & End Sem Examinations 2 5 Generic Subject Papers for B. A. Hons. Programme 3 6 Semester wise Structure for End Sem Examination of Generic Elective 4 SEMESTER I 7 I. Ability Enhancement Compulsory Course (AECC) 5 8 II. Generic Elective (GE 1) 5 9 III. Core Course –C 1 5 10 IV. Core Course- C 2 7 SEMESTER II 11 I. Environmental Studies (EVS) 8 12 II. Generic Elective (GE 2) 10 13 III. Core Course –C 3 10 14 IV. Core Course- C 4 12 SEMESTER III 15 I. Skill Enhancement Course (SEC 1) 13 16 II. Generic Elective (GE 3) 19 17 III. Core Course –C 5 19 18 IV. Core Course- C 6 21 19 V. Core Course- C 7 23 SEMESTER IV 20 I. Skill Enhancement Course (SEC 2) 25 21 II. Generic Elective (GE 4) 26 22 III. Core Course –C 8 26 23 IV. Core Course- C 9 28 ii HISTORY HONS. CBCS CURRICULUM RANCHI UNIVERSITY 24 V. -

R.K.D.F. UNIVERSITY, RANCHI Scheme

R.K.D.F. UNIVERSITY, RANCHI MASTER OF ARTS (History) Scheme The structure of the course will comprise Four-Papers in each Semester. First Semester Marks: 30 (MSE: 20Th. 1Hr + 5Attd. + 5Assign.) + 70 (ESE: 3Hrs)=100 Pass Marks (MSE:17 + ESE:28)=45 Mid Semester Examination (MSE): There will be two groups of questions in written examinations of 20 marks. Group A is compulsory and will contain five questions of very short answer type consisting of 1 mark each. Group B will contain descriptive type five questions of five marks each, out of which any three are to be answered. End Semester Examination (ESE): There will be two groups of questions. Group A is compulsory and will contain two questions. Question No.1 will be very short answer type consisting of five questions of 1 mark each. Question No.2 will be short answer type of 5 marks. Group B will contain descriptive type six questions of fifteen marks each, out of which any four are to be answered. Note: There may be subdivisions in each question asked in Theory Examinations The Mid Semester Examination shall have three components. (a) Two Semester Internal Assessment Test (SIA) of 20 Marks each, (b) Class Attendance Score (CAS) of 5 marks and (c) Class Performance Score (CPS) of 5 marks. “Best of Two” shall be applicable for computation of marks for SIA. R.K.D.F. UNIVERSITY, RANCHI MASTER OF ARTS (History) First Year Syllabus Semester – I Course Subject Subject Code M.A.(History) PRINCIPLES OF HISTORY PHS-101 PRINCIPLES OF HISTORY Theory: 60 Lectures; Tutorial: 15 Hrs. -

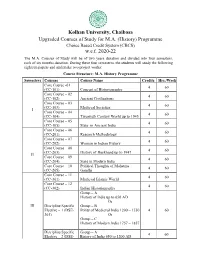

History) Programme Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) W.E.F

Kolhan University, Chaibasa Upgraded Courses of Study for M.A. (History) Programme Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) w.e.f. 2020-22 The M.A. Courses of Study will be of two years duration and divided into four semesters, each of six months duration. During these four semesters, the students will study the following eighteen papers and undertake two project works: Course Structure: M.A. History Programme Semesters Courses Course Name Credits Hrs./Week Core Course -01 4 60 (CC-101) Concept of Historiography Core Course – 02 4 60 (CC-102) Ancient Civilizations Core Course – 03 4 60 (CC-103) Medieval Societies I Core Course – 04 4 60 (CC-104) Twentieth Century World up to 1945 Core Course – 05 4 60 (CC-105) State in Ancient India Core Course – 06 4 60 (CC-201) Research Methodology Core Course – 07 4 60 (CC-202) Women in Indian History Core Course – 08 4 60 (CC-203) History of Jharkhand up to 1947 II Core Course – 09 4 60 (CC-204) State in Modern India Core Course – 10 Political Thoughts of Mahatma 4 60 (CC-205) Gandhi Core Course – 11 4 60 (CC-301) Medieval Islamic World Core Course – 12 4 60 (CC-302) Indian Historiography Group – A History of India up to 650 AD Or III Discipline Specific Group – B Elective – 1 (DSE- Polity of Medieval India 1200 – 1550 4 60 301) Or Group – C History of Modern India 1757 – 1857 Discipline Specific Group – A 4 60 Elective – 2 (DSE- History of India 650 to 1200 AD 302) Or Group – B Polity of Medieval India 1550-1750 Or Group – C History of Modern India 1859-1950 Project (PR) - 01[PR 6 120 - 301] Core Course -

Edition-201 English Meduimm-Book

Jharkhand English MeduimM-Book - Edition 201 © Jhssc Education Pvt Ltd 1. Jharkhand - An Introduction 2. First in Jharkhand 3. Largest,small,big in Jharkhand 4. Important years 5. History of Jharkhand 6. Tribal Revolt 7. Jharkhand movement 8. Geography of Jharkhand 9. River Valley Projects 10. Forest, Resources & wildlife 11. Jharkhand's population 12. Legislative and executive 13. Mineral Resources 14. Education system 15. Temple and memorial 16. Government schemes 17. Tribes of Jharkhand 18. Aart and culture 19. Festival, Music and language 20. Books and Authors 21. Sports & Nicknames 22. Famous Personality 23. Important pre yr q & current affairs Jharkhand-At a Glance Jharkhand ie 'Jhar' or 'Jhad', which is synonymous with forest in local language and Khand which means composed of 'small parts’. According to its name, It is basically a forest region that is created as a result of the Jharkhand movement. Due to abundance of minerals it is also called 'Ruhr' of India, which is a well known mineral dominant region in Germany. The Adivasi Mahasabha, formed around 1930s under the leadership of Jaipal Singh Munda, dreamed of a separate Jharkhand state first. In the year 2000, on 15th of November (the birth anniversary of the tribal hero Birsa Munda),Government of India created new state Jharkhand and thus became 28th state of India. Jharkhand was formed by carving out the southern part of Bihar Industrial city Ranchi is its capital. Other major cities of this state include Dhanbad, Bokaro and Jamshedpur. Jharkhand share its boundary with Bihar in the north, Uttar Pradesh and Chhattisgarh in the west, Odisha in the south and West Bengal in the east.