Toral Care of the Mentally Handicapped

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literatura Y Otras Artes: Hip Hop, Eminem and His Multiple Identities »

TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO « Literatura y otras artes: Hip Hop, Eminem and his multiple identities » Autor: Juan Muñoz De Palacio Tutor: Rafael Vélez Núñez GRADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES Curso Académico 2014-2015 Fecha de presentación 9/09/2015 FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS UNIVERSIDAD DE CÁDIZ INDEX INDEX ................................................................................................................................ 3 SUMMARIES AND KEY WORDS ........................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 5 1. HIP HOP ................................................................................................................... 8 1.1. THE 4 ELEMENTS ................................................................................................................ 8 1.2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................................. 10 1.3. WORLDWIDE RAP ............................................................................................................. 21 2. EMINEM ................................................................................................................. 25 2.1. BIOGRAPHICAL KEY FEATURES ............................................................................................. 25 2.2 RACE AND GENDER CONFLICTS ........................................................................................... -

“College-Level” Writing? Vol

What Is “College-Level” Writing? Is “College-Level” What is sequel to What Is “Coege-Level” Writing? (2006) highlights the What Is praical aects of teaching writing. By design, the essays in this collection focus on things all English and writing teachers concern themselves with on a daily basis—assignments, readings, and real “College-Level” student writing. e collection also seeks to extend the conversation begun in the rst volume by providing in-depth analysis and discussion of assign- C Vol. 2 Vol. ments and student writing. e goal is to begin a process of dening Writing? M “college-level” writing by example. Contributors include students, Y high school teachers, and college instructors in conversation with CM one another. MY Volume 2 CY Assignments, rough this pragmatic lens, the essays in this volume address other Sullivan • Blau • Tinberg CMY important issues related to college-level writing, including assign- K Readings, ment design, the AP test, the use of the ve-paragraph essay, as well as issues related to L2/ESL and Generation 1.5 students. and Student Writing Samples edited by Patrick Sullivan Howard Tinberg Sheridan Blau Copy Editor: Peggy Currid Production Editor: Carol Roehm Interior Design: Jenny Jensen Greenleaf Cover Design: Barbara Yale-Read NCTE Stock Number: 56766 ©2010 by the National Council of Teachers of English. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the copyright holder. Printed in the United States of America. -

Summer Camp Song Book

Summer Camp Song Book 05-209-03/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Numbers 3 Short Neck Buzzards ..................................................................... 1 18 Wheels .............................................................................................. 2 A A Ram Sam Sam .................................................................................. 2 Ah Ta Ka Ta Nu Va .............................................................................. 3 Alive, Alert, Awake .............................................................................. 3 All You Et-A ........................................................................................... 3 Alligator is My Friend ......................................................................... 4 Aloutte ................................................................................................... 5 Aouettesky ........................................................................................... 5 Animal Fair ........................................................................................... 6 Annabelle ............................................................................................. 6 Ants Go Marching .............................................................................. 6 Around the World ............................................................................... 7 Auntie Monica ..................................................................................... 8 Austrian Went Yodeling ................................................................. -

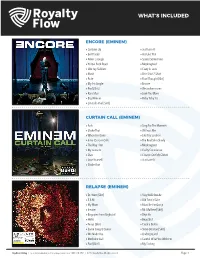

What's Included

WHAT’S INCLUDED ENCORE (EMINEM) » Curtains Up » Just Lose It » Evil Deeds » Ass Like That » Never Enough » Spend Some Time » Yellow Brick Road » Mockingbird » Like Toy Soldiers » Crazy in Love » Mosh » One Shot 2 Shot » Puke » Final Thought [Skit] » My 1st Single » Encore » Paul [Skit] » We as Americans » Rain Man » Love You More » Big Weenie » Ricky Ticky Toc » Em Calls Paul [Skit] CURTAIN CALL (EMINEM) » Fack » Sing For The Moment » Shake That » Without Me » When I’m Gone » Like Toy Soldiers » Intro (Curtain Call) » The Real Slim Shady » The Way I Am » Mockingbird » My name Is » Guilty Conscience » Stan » Cleanin Out My Closet » Lose Yourself » Just Lose It » Shake That RELAPSE (EMINEM) » Dr. West [Skit] » Stay Wide Awake » 3 A.M. » Old Time’s Sake » My Mom » Must Be the Ganja » Insane » Mr. Mathers [Skit] » Bagpipes from Baghdad » Déjà Vu » Hello » Beautiful » Tonya [Skit] » Crack a Bottle » Same Song & Dance » Steve Berman [Skit] » We Made You » Underground » Medicine Ball » Careful What You Wish For » Paul [Skit] » My Darling Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. All rights reserved. Page. 1 WHAT’S INCLUDED RELAPSE: REFILL (EMINEM) » Forever » Hell Breaks Loose » Buffalo Bill » Elevator » Taking My Ball » Music Box » Drop the Bomb On ‘Em RECOVERY (EMINEM) » Cold Wind Blows » Space Bound » Talkin’ 2 Myself » Cinderella Man » On Fire » 25 to Life » Won’t Back Down » So Bad » W.T.P. » Almost Famous » Going Through Changes » Love the Way You Lie » Not Afraid » You’re Never Over » Seduction » [Untitled Hidden Track] » No Love THE MARSHALL MATHERS LP 2 (EMINEM) » Bad Guy » Rap God » Parking Lot (Skit) » Brainless » Rhyme Or Reason » Stronger Than I Was » So Much Better » The Monster » Survival » So Far » Legacy » Love Game » Asshole » Headlights » Berzerk » Evil Twin Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. -

The Black Vernacular Versus a Cracker's Knack for Verses

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Arts Arts Research & Publications 2014-10-24 The black vernacular versus a cracker's knack for verses Flynn, Darin McFarland Books Flynn, D. (2014). The black vernacular versus a cracker's knack for verses. In S. F. Parker (Ed.). Eminem and Rap, Poetry, Race: Essays (pp. 65-88). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112323 book part "Eminem and Rap, Poetry, Race: Essays" © 2014 Edited by Scott F. Parker Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca The Black Vernacular Versus a Cracker’s Knack for Verses Darin Flynn Who would have ever thought that one of the greatest rappers of all would be a white cat? —Ice-T, Something from Nothing: The Art of Rap1 Slim Shady’s psychopathy is worthy of a good slasher movie. The soci- olinguistics and psycholinguistics behind Marshall Mathers and his music, though, are deserving of a PBS documentary. Eminem capitalizes on his lin- guistic genie with as much savvy as he does on his alter egos. He “flips the linguistics,” as he boasts in “Fast Lane” from Bad Meets Evil’s 2011 album Hell: The Sequel. As its title suggests, this essay focuses initially on the fact that rap is deeply rooted in black English, relating this to Eminem in the context of much information on the language of (Detroit) blacks. This linguistic excur- sion may not endear me to readers who hate grammar (or to impatient fans), but it ultimately helps to understand how Eminem and hip hop managed to adopt each other. -

Musikvideo: Not Afraid Fra Albummet Recovery (Eminem)

Musikvideo: Not Afraid fra albummet Recovery (Eminem) Tema: Om tro, tillid, ikke at frygte, men at turde træde ud på dybt vand, tage imod en hånd, gå igennem stormen og kaste sig ud i livet. Efter de flotte åbningsklip af Marshall (Eminem), der står på afsatsen af et højhustag, mens der skues over Newark, ser vi klip til kælderen, hvor han ”rhymer” i sin frustration. Selv om han ser ud til at have trukket sig tilbage fra selvmords overtonerne fra højhustaget, er han dog ikke kommet ud af mørket endnu. Man ser ham ”muret” inde, fortvivlet og fanget i sit liv. Han ser Market Street forvandle sig til en spejlsal, hvor han tvinges til at blive konfronteret med sit eget spejlbillede, som dog kun viser sig som brudstykker af ham selv. Han rammes dog af ly- set, frisættes fra kælder-tilværelsen, går ud i trafikken og stiller sig ud på kanten af en kata- stroferamt afsats. Her beslutter han sig til at springe ud, kaste sig ud over kanten, men frem- for at styrte i afgrunden, gribes han og flyver op med nye kræfter - afsted med Superman og Matrix metaforer i luften – for til sidst at stå på højhustaget igen. Denne gang ser han dog op i lyset og rækker hånden ud, mens han synger ” I´m not afraid.” Eminem opfordrer i sin sang: I´m not afraid - til ikke at være bange, men til at turde tage et standpunkt og til at tage imod den hånd, der rækkes ud, for vi er ikke alene, selv når vi går igennem stormen. -

![Alive [Lyrics, 132 Bpm, 4/4] [Default Arrangement] by Aodhan King and Alexander Pappas V1, V2, PC1, C, V3, V4, PC1, C, PC2, C×2](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1898/alive-lyrics-132-bpm-4-4-default-arrangement-by-aodhan-king-and-alexander-pappas-v1-v2-pc1-c-v3-v4-pc1-c-pc2-c%C3%972-2411898.webp)

Alive [Lyrics, 132 Bpm, 4/4] [Default Arrangement] by Aodhan King and Alexander Pappas V1, V2, PC1, C, V3, V4, PC1, C, PC2, C×2

Alive [Lyrics, 132 bpm, 4/4] [Default Arrangement] by Aodhan King and Alexander Pappas V1, V2, PC1, C, V3, V4, PC1, C, PC2, C×2 Verse 1 I was lost with a broken heart You picked me up now I'm set apart From the ash I am born again Forever safe in the Saviour's hands Verse 2 You are more than my words could say I'll follow You Lord for all my days Fix my eyes follow in Your ways Forever free in unending grace Pre-Chorus 1 'Cause You are You are You are my freedom We lift You higher lift You higher Your love Your love Your love never ending Oh oh oh Chorus You are alive in us Nothing can take Your place You are all we need Your love has set us free (oh oh) Verse 3 In the midst of the darkest night Let Your love be the shining light Breaking chains that were holding me You sent Your Son down and set me free Verse 4 Ev'rything of this world will fade I'm pressing on till I see Your face I will live that Your will be done I won't stop till Your kingdom come Pre-Chorus 2 You are You are You are my freedom We lift You higher You are You are You are my freedom We lift You higher lift You higher Your love Your love Your love never ending Oh oh oh © 2013 Hillsong Music Publishing 1 Not Afraid [Lyrics] [Default Arrangement] by Adeze Azubuike, David Anderson, Mia Fieldes, and Travis Ryan Verse 1 I have this confidence because I've seen the faithfulness of God The still inside the storm The promise of the shore I trust the power of Your Word Enough to seek Your Kingdom first Beyond the barren place beyond the ocean waves Chorus 1 When I walk through -

Be Not Afraid: Straight for Equality in Faith Communities

be not afraid help is on the way! preface Whether I want to deal with it or not, accepting gay people is a religious issue for me. Like many, I’m in that category of ‘Sure, I have a gay friend’ but often find myself trying to not think about what it means when my acceptance of my friend is in conflict with what my religion teaches me about him. And for me, not dealing with it means not talking about it with people from my church, even when it would mean speaking up on behalf of my friend. I avoid it because it is just too challenging and it is bound to end in an argument. I’m not proud of that, and I want a way to respond differently. Andrew, 39 Sound familiar? We’ve got some really good news for you: You’re not alone. Welcome to Straight for Equality. Straight for Equality is a project that started in 2007 as part of PFLAG National,* the original family and ally organization to the gay, lesbian, bi, and transgender (GLBT) community. The premise of the Straight for Equality project is pretty basic: There are many people out there who fall into the “I have a gay (or lesbian, or bi, or trans) friend and I want to be supportive” category, but don’t necessarily know what “be supportive” means—or, for that matter, if their support is even wanted. Our response is simple: Yes, your support is wanted and very much needed. More importantly, we can help you learn more about what your GLBT friends are facing, work through any of *PFLAG National is really Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays. -

Discography O 6.1 Number-One Singles • 7 Filmography • 8 Awards and Nominations • 9 Business Ventures • 10 See Also • 11 References O 11.1 Literature

Eminem From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Also known as Slim Shady October 17, 1972 (age 37), Saint Joseph, Born Missouri, United States Origin Detroit, Michigan, US Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper, record producer, actor, songwriter Years active 1995–present Mashin' Duck, Web, Interscope, Aftermath, Labels Shady Associated Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", The acts Alchemist, 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website http://www.eminem.com Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem (often styled "EMINƎM"), is an American rapper, record producer, actor and singer. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in the United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse, giving him a total of 11 Grammys in his career. In 2002, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. -

Lyrics for "Cleaning out My Closet"

Eminem - Cleaning out My Closet Lyrics Page 1 of 2 Home People Charts Events Submit Login Eminem Messages Info Songs Lyrics Send "Cleaning out My Closet" Ringtone to your [Intro] Where's my snare? I have no snare in my headphones - there you go Yeah.. yo, yo [Eminem] Get New Video Have you ever been hated or discriminated against? I have; I've been protested and demonstrated against Albums Picket signs for my wicked rhymes, look at the times Sick as the mind of the motherfuckin' kid that's behind All this commotion emotions run deep as ocean's explodin Tempers flarin' from parents just blow 'em off and keep g Not takin' nothin' from no one give 'em hell long as I'm b Keep kickin' ass in the mornin' and takin' names in the ev 1. Marshall Mathers LP Leave 'em with a taste as sour as vinegar in they mouth 18 songs See they can trigger me, but they'll never figure me out Look at me now; I bet ya probably sick of me now ain't y 2. E. [Video/DVD] I'm a make you look so ridiculous now 9 songs 3. Live In Europe [Chorus: Eminem] 16 songs I'm sorry momma! I never meant to hurt you! 4. Not Afraid I never meant to make you cry; but tonight 2 songs I'm cleanin' out my closet (one more time) 5. Marshall Mathers LP I said I'm sorry momma! 26 songs I never meant to hurt you! I never meant to make you cry; but tonight 6. -

Morning Worship August 2, 2020 God Calls Us to Worship the Prelude – “Variations of Jesus, Priceless Treasure ” – Jan Be

Morning Worship August 2, 2020 God Calls Us to Worship The Prelude – “Variations of Jesus, Priceless Treasure” – Jan Bender The Chiming of the Hour The Introit – “Be Thou Still” – Johann Franck Be thou still and learn of God. He will guide thy daily living, when in faith ye turn to him. Therefore daily thanks be giving, he will all thy hopes fulfill. Be thou still. In this quiet learn of his will. Be thou still. The Opening Hymn: Lift Up Your Hearts 43 “Guide Me, O My Great Redeemer” 1. Guide me, O my great Redeemer, pilgrim through this barren land; I am weak, but you are mighty; hold me with your powerful hand. Bread of heaven, bread of heaven, feed me now and evermore, feed me now and evermore. 2. Open now the crystal fountain, where the healing waters flow. Let the fire and cloudy pillar lead me all my journey through. Strong Deliverer, strong Deliverer, ever be my strength and shield, ever be my strength and shield. 3. When I tread the verge of Jordan, bid my anxious fears subside. Death of death, and hell’s destruction, land me safe on Canaan’s side. Songs of praises, songs of praises I will ever sing to you, I will ever sing to you. Amen. The Greeting The People’s Response: Amen. The Welcome We Come Humbly Before Our God The Call to Confession: Matthew 14:22-23 The Prayer of Confession The Assurance of Forgiveness: Isaiah 43:1-3a The Hymn: Lift Up Your Hearts 465:1,3 “Precious Lord, Take My Hand” 1. -

Police Crime Report

PPoolliiccee CCrriimmee BBuulllleettiinn Crime Prevention Bureau 26000 Evergreen Road, Southfield, Michigan (248) 796-5500 March 2, 2020 – March 8, 2020 Chief of Police Elvin Barren Prepared by Mark Malott Neighborhood Watch Coordinator 248-796-5415 Commercial Burglaries: Date/Time Address (block range) Method of Entry Description/Suspect Information From: 03/07/2020 29000 Southfield Rd. Keys were most R/P (employee for business) arrived at 3:30am. He 3:45pm ( Commercial - Bagels) likely used to discovered that the front door was unlocked. To: 03/08/2020 enter business. The manager for store arrived on scene and entered 3:30pm the business. She found the safe was open in the back and an undisclosed amount of cash was taken from the safe. There were no signs of forced entry on the front door or the safe. The manager advises that several employees have keys for business and know the combination for the safe. There are surveillance cameras at the business but they were not available at time of report. From: 03/06/2020 21000 Melrose Ave. No forced entry. R/P states he came into business on Sunday to pick up 6:00pm ( Commercial - Office) some equipment and noticed that several items were To: 03/08/2020 missing from the business. There were no signs of any 3:00pm forced entry. Suspect(s); Unknown, possibly cleaning crew. Taken; Appliances from the kitchen, computer monitors, flat screen televisions, and possibly materials from the shop area. Time Frame: Friday 03/06/2020, close of business 6:00pm- to the time of report 03/08/2020 at approx.