Garde Okpanachi Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senate Committee Report

THE 7TH SENATE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA COMMITTEE ON THE REVIEW OF THE 1999 CONSTITUTION REPORT OF THE SENATE COMMITTEE ON THE REVIEW OF THE 1999 CONSTITUTION ON A BILL FOR AN ACT TO FURTHER ALTER THE PROVISIONS OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA 1999 AND FOR OTHER MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWITH, 2013 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria referred the following Constitution alterations bills to the Committee for further legislative action after the debate on their general principles and second reading passage: 1. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.107), Second Reading – Wednesday 14th March, 2012 2. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.136), Second Reading – Thursday, 14th October, 2012 3. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.139), Second Reading – Thursday, 4th October, 2012 4. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.158), Second Reading – Thursday, 4th October, 2012 5. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.162), Second Reading – Thursday, 4th October, 2012 6. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.168), Second Reading – Thursday 1 | P a g e 4th October, 2012 7. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.226), Second Reading – 20th February, 2013 8. Ministerial (Nominees Bill), 2013 (SB.108), Second Reading – Wednesday, 13th March, 2013 1.1 MEMBERSHIP OF THE COMMITTEE 1. Sen. Ike Ekweremadu - Chairman 2. Sen. Victor Ndoma-Egba - Member 3. Sen. Bello Hayatu Gwarzo - “ 4. Sen. Uche Chukwumerije - “ 5. Sen. Abdul Ahmed Ningi - “ 6. Sen. Solomon Ganiyu - “ 7. Sen. George Akume - “ 8. Sen. Abu Ibrahim - “ 9. Sen. Ahmed Rufa’i Sani - “ 10. Sen. Ayoola H. Agboola - “ 11. Sen. Umaru Dahiru - “ 12. Sen. James E. -

LEADERSHIP (26 Ga Jimada Thani, 1440)

Litinin Don Allah Da Kishin Qasa 04.03.19 04 Ga Maris, 2019 LEADERSHIP (26 Ga Jimada Thani, 1440) Awww.leadershipayau.com yAJARIDAR HAUSA TA FARKO MAIU FITOWA KULLUM A NIJERIYA Leadership A Yau LeadershipAyau No: 308 N150 Zave: BCO Ta Nemi Qungiyoyin EU Da AU Su Tsawatarwa Atiku Daga Muhammad Abubakar kan irin matakan da yake ta qoqarin A takardu mabambanta da qungiyar A wasiqun na Qungiyar BCO, waxanda xauka na nasarar da Buhari ya samu akan ta turawa waxannan qungiyoyin EU da daraktan Sadarwa da tsare-tsarenta, Qungiyar kamfen ta Shugaban Qasa shi a zaven da ya gabata. AU. Inda qungiyar ta BCO ta ce, lallai Mallam Gidado Ibrahim ya rattabawa Muhammadu Buhari, wacce aka fi sani Qungiyar ta rubuta takarda ga Qungiyar akwai buqatar waxannan qungiyoyi su hannu, BCO ta ce, abin da ya fi dacewa da BCO, ta yi kira ga qasashen waje da su Tarayyar Turai da Tarayyar Qasashen yi gaggawar xaukar matakin da ya dace ga Atiku shi ne ya taya Buhari murna a tsawatar wax an takarar Shugaban Qasa Afirka kan wannan quduri nasu na son a domin tsamo dimokraxiyyar qasar daga maimakon qoqarin tada-zaune tsayen da na jam’iyyar PDP, Alhaji Atiku Abubakar tsawatarwa da Atiku Abubakar. halin da Atiku ke shirin jefa ta. yake ta qoqarin yi. Na San Babu Wanda Zai 4 Iya Yin Nasara Kan Buhari –Gwamnan Anambra ’Yan Bindiga Sun Kashe Mutum 5 A Jihar Kaduna Daga Bello Hamza, Abuja ‘Yan sanda a Jihar Kaduna sun tabbatar da kisan mutane biyar a ranar Asabar, da wata tawagar ‘yan bindiga da ba a san ko su wane ne ba suka aiwatar a qauyan Sabon Sara, da ke qaramar hukumar Giwa, ta Jihar. -

The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival

n the basis on solid fieldwork in northern Nigeria including participant observation, 18 Göttingen Series in Ointerviews with Izala, Sufis, and religion experts, and collection of unpublished Social and Cultural Anthropology material related to Izala, three aspects of the development of Izala past and present are analysed: its split, its relationship to Sufis, and its perception of sharīʿa re-implementation. “Field Theory” of Pierre Bourdieu, “Religious Market Theory” of Rodney Start, and “Modes Ramzi Ben Amara of Religiosity Theory” of Harvey Whitehouse are theoretical tools of understanding the religious landscape of northern Nigeria and the dynamics of Islamic movements and groups. The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival Since October 2015 Ramzi Ben Amara is assistant professor (maître-assistant) at the Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Sousse, Tunisia. Since 2014 he was coordinator of the DAAD-projects “Tunisia in Transition”, “The Maghreb in Transition”, and “Inception of an MA in African Studies”. Furthermore, he is teaching Anthropology and African Studies at the Centre of Anthropology of the same institution. His research interests include in Nigeria The Izala Movement Islam in Africa, Sufism, Reform movements, Religious Activism, and Islamic law. Ramzi Ben Amara Ben Amara Ramzi ISBN: 978-3-86395-460-4 Göttingen University Press Göttingen University Press ISSN: 2199-5346 Ramzi Ben Amara The Izala Movement in Nigeria This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Published in 2020 by Göttingen University Press as volume 18 in “Göttingen Series in Social and Cultural Anthropology” This series is a continuation of “Göttinger Beiträge zur Ethnologie”. -

Nasir El-Rufai Interviewer

An initiative of the National Academy of Public Administration, and the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs and the Bobst Center for Peace and Justice, Princeton University Oral History Program Series: Governance Traps Interview No: D1 Interviewee: Nasir el-Rufai Interviewer: Graeme Blair and Daniel Scher Date of Interview: 16 June 2009 Location: Washington, DC U.S.A. Innovations for Successful Societies, Bobst Center for Peace and Justice Princeton University, 83 Prospect Avenue, Princeton, New Jersey, 08540, USA www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties Use of this transcript is governed by ISS Terms of Use, available at www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties Innovations for Successful Societies Series: Governance Traps Oral History Program Interview number: D-1 ______________________________________________________________________ BLAIR: Just to confirm for the tape that you are consenting to the interview, it is a volunteer interview and you have read our consent documents. EL-RUFAI: You make it sound like you are asking me to marry you and it is a big decision, I consent. [laughter] BLAIR: Thank you very much for agreeing to share your views with us and with other reform leaders that we will disseminate this to. Until very recently you were involved in Nigeria’s reform program at several levels, first in the Bureau of Public Enterprises and then as Minister for Abuja and in several informal capacities as part of President (Olusegun) Obasanjo’s economic reform team. We’d like to speak to you about these experiences first as a member of the larger reform team and then more particular questions about your experience as Minister for Abuja. -

FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Wednesday, 15Th May, 2013 1

7TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECOND SESSION NO. 174 311 THE SENATE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Wednesday, 15th May, 2013 1. Prayers 2. Approvalof the Votes and Proceedings 3. Oaths 4. Announcements (if any) 5. Petitions PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. National Agricultural Development Fund (Est. etc) Bill 2013(SB.299)- First Reading Sen. Abdullahi Adamu (Nasarauia North) 2. Economic and Financial Crime Commission Cap E 1 LFN 2011 (Amendment) Bill 2013 (SB. 300) - First Reading Sen. Banabas Gemade (Be1l11eNorth East) 3. National Institute for Sports Act Cap N52 LFN 2011(Amendment) Bill 2013(SB.301)- First Reading Sen. Banabas Gemade (Benue North East) 4. National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) Act Cap N30 LFN 2011 (Amendment) Bill 2013 (SB.302)- First Reading Sen. Banabas Gemade tBenue North East) 5. Federal Highways Act Cap F 13 LFN 2011(Amendment) Bill 2013(SB. 303)- First Reading Sen. Banabas Gemade (Benue North East) 6. Energy Commission Act Cap E 10 LFN 2011(Amendment) Bill 2013 (SB.304)- First Reading Sen. Ben Ayade (Cross Riner North) 7. Integrated Farm Settlement and Agro-Input Centres (Est. etc) Bill 2013 (SB.305)- First Reading Sen. Ben Ayade (Cross River North) PRESENTATION OF A REPORT 1. Report of the Committee on Ethics, Privileges and Public Petitions: Petition from Inspector Emmanuel Eldiare: Sen. Ayo Akinyelure tOndo Central) "That the Senate do receive the Report of the Committee on Ethics, Privileges and Public Petitions in respect of a Petition from INSPECTOR EMMANUEL ELDIARE, on His Wrongful Dismissal by the Nigeria Police Force" - (To be laid). PRINTED BY NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PRESS, ABUJA 312 Wednesday, 15th May, 2013 174 ORDERS OF THE DAY MOTION 1. -

Global Journal of Human Social Science from Colonialism Not Very Long Ago

Online ISSN : 2249-460X Print ISSN : 0975-587X Natural Resource Governance Nigeria’s Extractive Industry Trends in Employment Relations Presidential Elections in Nigeria VOLUME 15 ISSUE 7 VERSION 1.0 Global Journal of Human-Social Science: F Political Science Global Journal of Human-Social Science: F Political Science Volume 15 Issue 7 (Ver. 1.0) Open Association of Research Society Global Journals Inc. *OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ (A Delaware USA Incorporation with “Good Standing”; Reg. Number: 0423089) Sponsors:Open Association of Research Society Social Sciences. 2015. Open Scientific Standards $OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG 7KLVLVDVSHFLDOLVVXHSXEOLVKHGLQYHUVLRQ Publisher’s Headquarters office RI³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 6FLHQFHV´%\*OREDO-RXUQDOV,QF Global Journals Headquarters $OODUWLFOHVDUHRSHQDFFHVVDUWLFOHVGLVWULEXWHG 301st Edgewater Place Suite, 100 Edgewater Dr.-Pl, XQGHU³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 6FLHQFHV´ Wakefield MASSACHUSETTS, Pin: 01880, 5HDGLQJ/LFHQVHZKLFKSHUPLWVUHVWULFWHGXVH United States of America (QWLUHFRQWHQWVDUHFRS\ULJKWE\RI³*OREDO USA Toll Free: +001-888-839-7392 -RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO6FLHQFHV´XQOHVV USA Toll Free Fax: +001-888-839-7392 RWKHUZLVHQRWHGRQVSHFLILFDUWLFOHV 1RSDUWRIWKLVSXEOLFDWLRQPD\EHUHSURGXFHG Offset Typesetting RUWUDQVPLWWHGLQDQ\IRUPRUE\DQ\PHDQV HOHFWURQLFRUPHFKDQLFDOLQFOXGLQJ Global Journals Incorporated SKRWRFRS\UHFRUGLQJRUDQ\LQIRUPDWLRQ 2nd, Lansdowne, Lansdowne Rd., Croydon-Surrey, VWRUDJHDQGUHWULHYDOV\VWHPZLWKRXWZULWWHQ SHUPLVVLRQ Pin: CR9 2ER, United Kingdom 7KHRSLQLRQVDQGVWDWHPHQWVPDGHLQWKLV ERRNDUHWKRVHRIWKHDXWKRUVFRQFHUQHG -

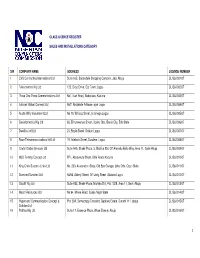

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

The Jonathan Presidency, by Abati, the Guardian, Dec. 17

The Jonathan Presidency By Reuben Abati Published by The Jonathan Presidency The Jonathan Presidency By Reuben Abati A review of the Goodluck Jonathan Presidency in Nigeria should provide significant insight into both his story and the larger Nigerian narrative. We consider this to be a necessary exercise as the country prepares for the next general elections and the Jonathan Presidency faces the certain fate of becoming lame-duck earlier than anticipated. The general impression about President Jonathan among Nigerians is that he is as his name suggests, a product of sheer luck. They say this because here is a President whose story as a politician began in 1998, and who within the space of ten years appears to have made the fastest stride from zero to “stardom” in Nigerian political history. Jonathan himself has had cause to declare that he is from a relatively unknown village called Otuoke in Bayelsa state; he claims he did not have shoes to wear to school, one of those children who ate rice only at Xmas. When his father died in February 2008, it was probably the first time that Otuoke would play host to the kind of quality crowd that showed up in the community. The beauty of the Jonathan story is to be found in its inspirational value, namely that the Nigerian dream could still take on the shape of phenomenal and transformational social mobility in spite of all the inequities in the land. With Jonathan’s emergence as the occupier of the highest office in the land, many Nigerians who had ordinarily given up on the country and the future felt imbued with renewed energy and hope. -

SERAP Petition to AG Over Double Emoluments for Ex-Govs Now

14 July 2017 Mr. Abubakar Malami (SAN) Attorney-General of the Federation and Minister of Justice, Federal Ministry of Justice, Shehu Shagari Way, Abuja Dear Mr. Abubakar Malami (SAN), Re: Request to challenge the legality of states’ laws granting former governors and now serving senators and ministers double pay, life pensions and seek recovery of over N40bn of public funds Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP) is writing to request you to use your good offices as a defender of public interest, and exercise your powers under Section 174(1) of the Constitution of Nigeria 1999 (as amended), to urgently institute appropriate legal actions to challenge the legality of states’ laws permitting former governors, who are now senators and ministers to enjoy governors’ emoluments while drawing normal salaries and allowances in their new political offices; and to seek full recovery of public funds from those involved. This request is entirely consistent with Nigeria’s international anticorruption obligations under the UN Convention against Corruption, to which the country is a state party. We request that you take this step within 7 days of the receipt and/or publication of this letter, failing which SERAP will institute legal proceedings to compel the discharge of constitutional duty and full compliance with Nigeria’s international obligations and commitments. SERAP is a non-governmental organization dedicated to strengthening the socio-economic welfare of Nigerians by combatting corruption and promoting transparency and accountability. SERAP received the Wole Soyinka Anti-Corruption Defender Award in 2014. It has also been nominated for the UN Civil Society Award and Ford Foundation’s Jubilee Transparency Award. -

The Judiciary and Nigeria's 2011 Elections

THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS CSJ CENTRE FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE (CSJ) (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS Written by Eze Onyekpere Esq With Research Assistance from Kingsley Nnajiaka THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiii First Published in December 2012 By Centre for Social Justice Ltd by Guarantee (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) No 17, Flat 2, Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, P.O. Box 11418 Garki, Abuja Tel - 08127235995; 08055070909 Website: www.csj-ng.org ; Blog: http://csj-blog.org Email: [email protected] ISBN: 978-978-931-860-5 Centre for Social Justice THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiiiiii Table Of Contents List Of Acronyms vi Acknowledgement viii Forewords ix Chapter One: Introduction 1 1.0. Monitoring Election Petition Adjudication 1 1.1. Monitoring And Project Activities 2 1.2. The Report 3 Chapter Two: Legal And Political Background To The 2011 Elections 5 2.0. Background 5 2.1. Amendment Of The Constitution 7 2.2. A New Electoral Act 10 2.3. Registration Of Voters 15 a. Inadequate Capacity Building For The National Youth Service Corps Ad-Hoc Staff 16 b. Slowness Of The Direct Data Capture Machines 16 c. Theft Of Direct Digital Capture (DDC) Machines 16 d. Inadequate Electric Power Supply 16 e. The Use Of Former Polling Booths For The Voter Registration Exercise 16 f. Inadequate DDC Machine In Registration Centres 17 g. Double Registration 17 2.4. Political Party Primaries And Selection Of Candidates 17 a. Presidential Primaries 18 b. -

Composition of Senate Committees Membership

LIST OF SPECIAL AND STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE 8TH ASSEMBLY-SENATE COMMITTEE ON AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT S/N NAMES MEMBERSHIP 1 Sen. Abdullahi Adamu Chairman 2 Sen. Theodore Orji Deputy Chairman 3 Sen. Shittu Muhammad Ubali Member 4 Sen. Adamu Muhammad Aliero Member 5 Sen. Abdullahi Aliyu Sabi Member 6 Sen. Bassey Albert Akpan Member 7 Sen. Yele Olatubosun Omogunwa Member 8 Sen. Emmanuel Bwacha Member 9 Sen. Joseph Gbolahan Dada Member COMMITTEE ON ARMY S/N NAMES MEMBERSHIP 1. Sen. George Akume Chairman 2 Sen. Ibrahim Danbaba Deputy Chairman 3 Sen. Binta Masi-Garba Member 4 Sen. Abubakar Kyari Member 5 Sen. Mohammed Sabo Member 6 Sen. Abdulrahman Abubakar Alhaji Member 7 Sen. Donald Omotayo Alasoadura Member 8 Sen. Lanre Tejuosho Adeyemi Member 9 Sen. James Manager Member 10 Sen. Joseph Obinna Ogba Member COMMITTEE ON AIRFORCE S/N NAMES MEMBERSHIP 1 Sen. Duro Samuel Faseyi Chairman 2 Sen. Ali Malam Wakili Deputy Chairman 3 Sen. Bala Ibn Na'allah Member 4 Sen. Bassey Albert Akpan Member 5 Sen. David Umaru Member 6 Sen. Oluremi Shade Tinubu Member 7 Sen. Theodore Orji Member 8 Sen. Jonah David Jang Member 9. Sen. Shuaibu Lau Member COMMITTEE ON ANTI-CORRUPTION AND FINANCIAL CRIMES S/N NAMES MEMBERSHIP 1 Sen. Chukwuka Utazi Chairman 2 Sen. Mustapha Sani Deputy Chairman 3 Sen. Mohammed Sabo Member 4 Sen. Bababjide Omoworare Member 5 Sen. Monsurat Sumonu Member 6 Sen. Isa Hamma Misau Member 7 Sen. Dino Melaye Member 8 Sen. Matthew Urhoghide Member COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS S/N NAMES MEMBERSHIP 1 Sen. Danjuma Goje Chairman 2 Sen. -

The Military and the Challenge of Democratic Consolidation in Nigeria: Positive Skepticism and Negative Optimism

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 15, ISSUE 4, 2014 Studies The Military And The Challenge Of Democratic Consolidation In Nigeria: Positive Skepticism And Negative Optimism Emmanuel O. Ojo Introduction This paper is an attempt to consider the role of the military in Nigeria’s democratic transitions. The paper has one major thrust – an in-depth analysis of military role in democratic transitions in Nigeria - the fundamental question, however, is: can the military ever be expected or assumed to play any major role in building democracy? The reality on the ground in Africa is that the military as an institution has never been completely immune from politics and the role of nation-building. However, whether they have been doing that perfectly or not is another question entirely which this paper shall address. The extant literature on civil-military relations generally is far from being optimistic that the military can discharge that kind of function creditably. Nonetheless, perhaps by sheer providence, they have been prominent both in political transitions and nation-building in Africa. It is against this backdrop of both pessimism and optimism that necessitated this caption an ‘oxymoron’- a figure of speech which depicts the contradictory compatibility in terms of civil-military relations in Nigeria. It is important to note that Nigeria’s democratization march has been a chequered one. Ben Nwabueze identified five different phases of Nigeria’s ©Centre of Military and Strategic Studies, 2014 ISSN : 1488-559X JOURNAL OF MILITARY AND