Potential Transportation Improvements and Land Use Impacts in the Elysian Fields Corridor Caroline Lanford University of New Orleans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

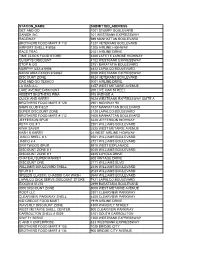

Posted on May 5, 2021 Sites with Asterisks (**) Are Able to Vaccinate 16-17 Year Olds

Posted on May 5, 2021 Sites with asterisks (**) are able to vaccinate 16-17 year olds. Updated at 4:00 PM All sites are able to vaccinate adults 18 and older. Visit www.vaccinefinder.org for a map of vaccine sites near you. Parish Facility Street Address City Website Phone Acadia ** Acadia St. Landry Hospital 810 S Broadway Street Church Point (337) 684-4262 Acadia Church Point Community Pharmacy 731 S Main Street Church Point http://www.communitypharmacyrx.com/ (337) 684-1911 Acadia Thrifty Way Pharmacy of Church Point 209 S Main Street Church Point (337) 684-5401 Acadia ** Dennis G. Walker Family Clinic 421 North Avenue F Crowley http://www.dgwfamilyclinic.com (337) 514-5065 Acadia ** Walgreens #10399 806 Odd Fellows Road Crowley https://www.walgreens.com/covid19vac Acadia ** Walmart Pharmacy #310 - Crowley 729 Odd Fellows Road Crowley https://www.walmart.com/covidvaccine Acadia Biers Pharmacy 410 N Parkerson Avenue Crowley (337) 783-3023 Acadia Carmichael's Cashway Pharmacy - Crowley 1002 N Parkerson Avenue Crowley (337) 783-7200 Acadia Crowley Primary Care 1325 Wright Avenue Crowley (337) 783-4043 Acadia Gremillion's Drugstore 401 N Parkerson Crowley https://www.gremillionsdrugstore.com/ (337) 783-5755 Acadia SWLA CHS - Crowley 526 Crowley Rayne Highway Crowley https://www.swlahealth.org/crowley-la (337) 783-5519 Acadia Miller's Family Pharmacy 119 S 5th Street, Suite B Iota (337) 779-2214 Acadia ** Walgreens #09862 1204 The Boulevard Rayne https://www.walgreens.com/covid19vac Acadia Rayne Medicine Shoppe 913 The Boulevard Rayne https://rayne.medicineshoppe.com/contact -

Riverfront Expressway Cancellation, Shuddering at the New Orleans That Could Have Been

Geographies of New Orleans Fifty Years After Riverfront Expressway Cancellation, Shuddering at the New Orleans That Could Have Been Richard Campanella Geographer, Tulane School of Architecture [email protected] Published in the New Orleans Picayune-Advocate, August 12, 2019, page 1. Fifty years ago this summer, reports from Washington D.C. reached New Orleans that John Volpe, secretary of the Department of Transportation under President Richard Nixon, had cancelled the Riverfront Expressway—the high-speed, elevated interstate slated for the French Quarter. The stunning news, about a wildly controversy plan that had divided the community for years, was met with elation by the city’s growing preservationist movement, and head-shaking disappointment by local leaders in both the public and private sectors. A half-century on, the cancellation and the original proposal invite speculation —part mental exercise, part cautionary tale—about what greater New Orleans might look like today had the Riverfront Expressway gone forward. And it very nearly did: conventional wisdom at the time saw the new infrastructure as an inevitable step toward progress, following the lead of many other waterfront cities, including New York, San Francisco, and Seattle. But first, a recap on how the New Orleans plan got to Volpe’s desk. Rendering from Robert Moses' Arterial Plan for New Orleans, 1946, page 11, courtesy collection of R. Campanella The initial concept for the Riverfront Expressway emerged from a post-World War II effort among state and city leaders to modernize New Orleans’ antiquated regional transportation system. Toward that end, the state Department of Highways hired the famous—many would say infamous—New York master planner Robert Moses, who along with Andrews & Clark Consulting Engineers, released in 1946 his Arterial Plan for New Orleans. -

Gentilly Retail Study: 2009

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Planning and Urban Studies Reports and Presentations Department of Planning and Urban Studies 5-2009 Gentilly Retail Study: 2009 Department of Planning and Urban Studies, University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/plus_rpts Part of the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Department of Planning and Urban Studies, University of New Orleans, "Gentilly Retail Study: 2009" (2009). Planning and Urban Studies Reports and Presentations. Paper 5. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/plus_rpts/5 This Study is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Planning and Urban Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Planning and Urban Studies Reports and Presentations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gentilly Retail Study: 2009 university of new orleans urban and regional planning May 2009 Graduate Student Planning Team: Chris Aghayan Lisa Kamuf Rosie Lacy By: Krista Lestina University of New Orleans Lucas Lilly Masters of Urban and Regional Michelle Little Planning Larry Massey MURP 6720 Caps tone, Spr ing 2009 Matthew Mourning Robert Peterson Professors: Catherine Poudin Dr. Renia Ehrenfeucht Michael Powers DMlDr. Marla NlNelson Jason Stopa Jason Tudor EXECUTIVE SUMARY 001 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The following report is an analysis of retail in Gentilly in the Any regional scale retail development will face competition Sppgring 2009 term with some updates throughout the semester from neiggghboring Jefferson Parish. Additionally, aformerhigh (site inventory was taken in the last two weeks of January and profile retail development in New Orleans East is being first week of February). -

Press Street: a Concept for Preserving, Reintroducing and Fostering Local History Brian J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Press Street: a concept for preserving, reintroducing and fostering local history Brian J. McBride Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Landscape Architecture Commons Recommended Citation McBride, Brian J., "Press Street: a concept for preserving, reintroducing and fostering local history" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2952. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2952 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRESS STREET: A CONCEPT FOR PRESERVING, REINTRODUCING, AND FOSTERING LOCAL HISTORY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agriculture and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Landscape Architecture in The School of Landscape Architecture by Brian J. McBride B.S., Louisiana State University, 1994 May 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to recognize a number of people for providing assistance, insight and encouragement during the research and writing of this thesis. Special thanks to the faculty and staff of the School of Landscape Architecture, especially to Max Conrad, Van Cox and Kevin Risk. To all without whom I could not have completed this process, especially my parents for their persistence; and my wife, for her continued love and support. -

Station Name Submitted Address Get And

STATION_NAME SUBMITTED_ADDRESS GET AND GO 1001 STUMPF BOULEVARD DANISH INC 101 WESTBANK EXPRESSWAY RACEWAY 989 MANHATTAN BOULEVARD BROTHERS FOOD MART # 113 1227 VETERANS BOULEVARD AIRPORT SHELL # 8058 1205 AIRLINE HIGHWAY RACE TRAC 2101 AIRLINE DRIVE TIME CLOCK FOOD STORE 4400 LAFITTE LAROSE HIGHWAY QUICKYS DISCOUNT 4102 WESTBANK EXPRESSWAY STOP N GO 3751 BARATATIA BOULEVARD MURPHY USA # 6906 4822 LAPALCO BOULEVARD BARATARIA EXXON # 58087 5000 WESTBANK EXPRESSWAY DISCOUNT ZONE 8824 VETERANS BOULEVARD GAS AND GO TEXACO 5001 AIRLINE DRIVE LA GAS LLC 4457 WEST METAIRIE AVENUE LAKE AVENUE DISCOUNT 200 LIVE OAK STREET HEBERT BROTHERS FINA 978 AVENUE A QUICK AND KARRY 9528 WESTBANK EXPRESSWAY SUITE A BROTHERS FOOD MART # 128 2901 HIGHWAY 90 SAMS CLUB # 8221 1527 MANHATTAN BOULEVARD SUPER DISCOUNT ZONE 2120 LAPALCO BOULEVARD BROTHERS FOOD MART # 112 1600 MANHATTAN BOULEVARD JEFFERSON SPUR 3220 JEFFERSON HIGHWAY RETIF OIL # 1 2201 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD KWIK SAVER 2525 WEST METAIRIE AVENUE KASH N KARRY 22 WEST AIRLINE HIGHWAY JASCO SHELL # 3 3501 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD JASCO # 4 2721 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD DRIFTWOOD SPUR 8910 WEST ESPLANADE DISCOUNT ZONE # 1 4045 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD DISCOUNT ZONE # 1 2845 LOYOLA DRIVE CHATEAU SUPER MARKET 600 VINTAGE DRIVE DISCOUNT ONE 2111 WILLIAMS BLVD WILLIAMS BOULEVARD SHELL 2436 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD SPUR # 1 2023 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD SPEEDS CLASSIC CHASSIS CAR WASH 3940 WILLIAMS BOULEVARD LAPALCO QICK SERVE DISCOUNT STORE 7421 LAPALCO BOULEVARD EXXON # 51275 2699 BARATARIA BOULEVARD 8000 DISCOUNT ZONE 8000 WEST METAIRIE AVENUE -

Electric Avenue Our Own Champs-Élysées Was Once Extraordinary—And Could Be Again

Cityscapes: A Geographer's View of the New Orleans Area Electric Avenue Our Own Champs-Élysées Was Once Extraordinary—and Could Be Again Richard Campanella New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 10, 2018 Only one major artery in New Orleans connects the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain with a single, straight, nearly longitudinal line. Unusually wide and grassy, the avenue spans the city’s full geographical gamut, from natural levee to former backswamp, to ridge, former marsh, and manmade lakefront. Historically, it witnessed growth from the Napoleonic Age to the Space Age. Architecturally, it hosts everything from an 1820 Creole cottage, to 1850s Greek Revival storehouses, to 1890s Victorian Italianate shotguns, to 1920s Spanish Villas, to 1960s ranch houses and post-Katrina houses jacked up on pilings. Demographically, it’s a cross-section of local society, in terms of class, race, and nativity, running from the gentrified historic districts at its foot to the middle-class families of Gentilly, to the suburban-feeling Lakefront and UNO campus. Spatially, its axial position drove the geometry of fully six square miles of subdivisions and nearly every street, block and lot therein, while also giving it convenient access to major east-west arteries. The avenue is Elysian Fields, and in my estimation, it’s one of the most interesting and least appreciated corridors in the metropolis, one that has the potential to live up to the grandeur of its name. I’ll leave the urban planning ideas for another time; my purpose here is to recount how this sui generis pathway came into place, and perhaps that history will spawn ideas of how—or Drone photo of Elysian Fields Avenue by Lorenzo Serafini Boni 2017 whether—to make this place more special. -

Gentilly Terrace Neighborhood, Planning District Six

Gentilly Terrace Neighborhood Planning District 6 Rebuilding Plan Gentilly Terrace Neighborhood, Planning District Six Introduction Table of Contents Approximately 100 days after Hurricane Katrina Basic assumptions also formed the basis for the Acknowledgements Introduction 2 struck, Motion M-05-592 was unanimously neighborhood rebuilding plan: passed by the City Council of New Orleans. This 1. That a flood protection system will be With grateful appreciation the planning team A. Gentilly Terrace Neighborhood motion ensured that community-based, designed to withstand future catastropic would like to thank all the residents of Location & History 3 neighborhood-by-neighborhood planning would loss from a 1 in 100 year storm and that District 6 who participated in this planning Recovery Vision & Goals 4 be central to decisions associated with the this is a commitment by the federal process and without whose participation this Planning Process 5 recovery of the most devastated areas of New government. plan would not be possible. Neighborhood Concerns 7 Orleans. The City Council was adamant that the people most impacted by the storm would play a 2. That stringent building codes will be Project Directory B. Pre-Hurricane Katrina central role in defining the future of their implemented to further limit wind Neighborhood Existing Conditions 9 communities. Overall, 47 of the 73 damage. City of New Orleans Land-Use and Zoning 9 neighborhoods delineated by the City’s Planning C. Ray Nagin, Mayor Pre-Katrina Demographic Profile 10 Commission have had plans prepared as part of 3. That the basic urban structure of the city Income & Household Characteristics 10 this process. -

Restoring Claiborne Avenue Alternatives for the Future of Claiborne Avenue

Restoring Claiborne Avenue Alternatives for the Future of Claiborne Avenue A Report to the Claiborne Corridor Improvement Coalition and Congress for the New Urbanism Prepared by Smart Mobility Inc. and Waggonner & Ball Architects 15 July 2010 CLAIBORNE CORRIDOR IMPROVEMENT COALITION The mission of the Claiborne Corridor Improvement Coalition is to plan and advocate for the transformation of the Claiborne Corridor into a healthy, vibrant boulevard that will not only serve as an anchor for the Corridor’s neighborhoods, but for the whole city of New Orleans. This report is the result of the efforts of the Coalition to gather information and inform the community about the alternatives for the Claiborne Avenue/I‐10 Corridor. The Coalition was formed by NEWCITY Neighborhood Partnerships, a coalition of developers, funders, neighborhood organizations, service providers, churches & faith‐ based groups, schools & universities, and government agencies focused on educational, economic, health, and housing development in the Tremé/Lafitte and Tulane/Gravier neighborhoods. The report has been prepared for the Coalition by the Congress for the New Urbanism, a national leader in promoting walkable, neighborhood‐based development as an alternative to sprawl, with assistance from the National Endowment of the Arts and the Ford Foundation. Members: Vaughn Fauria, NewCorp Inc., Co‐Chair, Claiborne Corridor Improvement Coalition (CCIC) Lisa Amoss, Broad Community Connections Bill Borah, Smart Growth for Louisiana Arianne Cousin, Urban Development Research Center Jack Davis, Smart Growth for Louisiana, Co‐Chair, CCIC Clifton James, Urban Development Research Center, Co‐Chair, CCIC Jim Kelly, Providence Community Housing/Catholic Charities, Co‐Chair, CCIC Nick Roosevelt, NEWCITY Neighborhood Partnership Daniel Samuels, Architect John Norquist, Congress for the New Urbanism Nora Beck, Congress for the New Urbanism Report Prepared for: Consultant Team: Lucy Gibson, P.E. -

Certified Small Entrepreneur (Hudson Initiative) Vendor List Alpha - LAPAC Use Ctrl + F to Search Within the Report

Certified Small Entrepreneur (Hudson Initiative) Vendor List Alpha - LAPAC Use Ctrl + F to search within the report. This report includes vendors that have certified with LED and registered with the Office of State Procurement. If your business does not appear on this list, click here to register. Name Contact Address City State Zip Phone FAX 1ST LEGACY LOGGING & LOGISTICS MEAGAN TUCKER 5705 E TEXAS ST, UNIT 55 BOSSIER CITY LA 71111 (318)489-8654 (000)000-0000 1st Team Insurance Agency Harold Williams 3745 Choctaw Dr Baton Rouge LA 70805 (225)806-6923 (225)372-8105 225 SWEETS LLC TONYA SMITH 1079 S TINLEY DRIVE BATON ROUGE LA 70815 (225)773-4952 (000)000-0000 2C'S CONSULTING, LLC CARLA CHIASSON 806 FONDA ST PARADIS LA 70080 (504)319-0275 (000)000-0000 3 G SERVICE GROUP, INC. GENEVA GREEN 205 CABINET DR. AVONDALE LA 70094 (504)302-1600 (000)000-0000 RANADA SANTIAGO- 360 TRUCKING LLC 2913 LAKEWOOD DRIVE VIOLET LA 70092 (504)915-5051 (504)592-7866 ROBINSON 3B OUTDOOR EQUIPMENT INC MATT BRIDGES 2528 FERRAND ST MONROE LA 71201 (318)366-8627 (318)855-3461 3SOUTH LLC CHARLOTTE JOHNSTON 3175 CONWAY DR BATON ROUGE LA 70809 (504)858-1955 (000)000-0000 4HP, LLC CHELO MCGILL 4001 S POST OAK NEW ORLEANS LA 70131 (000)000-0000 (000)000-0000 4NSIC SERVICES OF LOUISIANA LLC JANELLE DUGAS 3419 NW EVANGELINE THRUWAY CARENCRO LA 70520 (337)298-1380 (000)000-0000 64 PARISH STUDIO JENNIFER FINLEY 8954 BAYSIDE AVE BATON ROUGE LA 70806 (225)954-0403 (000)000-0000 A & E Enterprise Management, LLC Andrea Lowe 78 Sawgrass Drive La Place LA 70068 (504)355-1512 (000)000-0000 A & G CONSULTING GROUP, LLC GERARD BELL 12225 BRIANNA AVE BATON ROUGE LA 70818 (337)258-2451 (000)000-0000 A B COMPUTER SOLUTIONS INC Jason Brady 3980 FLORIDA ST MANDEVILLE LA 70448 (985)624-3092 (985)624-3994 A M & M MASONRY, INC. -

Kenner Community Resource Inventory

Tripp Umbach completed an inventory of community resources available in the OMC‐Kenner service area using resources identified by the MHCNO, internet research and United Way’s 211 First Call for Help community resource database. Using the parishes which define the OMC‐Kenner community, 365 community resources were identified with the capacity to meet the three community health needs identified in the MHCNO CHNA. (Please refer to the Community Health Needs Assessment Report to review the detailed community needs.) INVENTORY OF COMMUNITY RESOURCES AVAILABLE TO ADDRESS COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS IDENTIFIED IN THE MHCNO CHNA ABUSE SUBSTANCE AND HEALTH Care CARE Management TO providers/facilities Education Screenings Preparation of Skills Organization/Provider Counties Served Contact Information Zip Code Parish Internet Information Population Served Services Provided EDUCATION Health Nutrition Personalized Food Financial Life BEHAVIORAL Suicide Lack ACCESS Health Prevention 1ST CLASS CARE, EVERY TIME No restrictions 2200 Veterans Blvd., Suite 115 70062 Jefferson More Information No restrictions Provides home healthcare. Children's Choice Kenner, LA 70062 Waiver. Greater New Orleans Area Application * XXXXXX* XX * XX Phone: (504) 466‐1550 Center for Medicaid. 40TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT ADULT St. John the Baptist 104 Ormond Blvd, Suite B 70068 St. John the More Information Adults involved with the Provides substance abuse services. COURT OUTPATIENT La Place, LA 70068 Baptist court system * XX COUNSELING Phone: (985)359‐3315 A BEAM OF LIGHT No restrictions 5201 WestBank Expressway 70072 Jefferson More Information No restrictions Provides home healthcare and assistance with Marrero, LA 70072 independent living. * XXXXXX* XX * XX Phone: (504) 328‐1627 (866) 328‐1627 A COMMUNITY APPROACH TO No restrictions 4480 General DeGaulle Drive Suite 202 70131 Orleans More Information No restrictions Provides home healthcare. -

Milneburg Richard Campanella Published in the Times-Picayune-New Orleans Advocate, Sunday, October 6, 2019, Page 1

Geographies of New Orleans Where “I’ll Just Do as I D__n Please:” A Historical Geography of Milneburg Richard Campanella Published in the Times-Picayune-New Orleans Advocate, Sunday, October 6, 2019, page 1. Author’s note: This is the second in a series exploring the coastal communities that once surrounded greater New Orleans, principally along the brackish waters of the tidal lagoon known as Lake Pontchartrain. Last month we looked at Spanish Fort; today we examine its neighbor to the east. Though mostly gone now, these hamlets remind us that New Orleans, a riverine and deltaic city, may also be considered a coastal city. One summer day in 1828, a group of businessmen met in a French Quarter coffeehouse to plan a new transportation technology for New Orleans: the railroad. After obtaining a state charter in 1830 to form the Pontchartrain Railroad Company, they decided to route the tracks along the Marigny Canal on Elysian Fields Avenue and continue straight north. That trajectory, traceable to the circa-1740s Dubreuil Canal, pinpointed an obscure spot on the wild shore of Lake Pontchartrain where the rail cars would transfer cargo with lake vessels. Thus was born Milneburg. The name for the forthcoming lakeside settlement came from the Scottish businessman Alexander Milne, who prospered as a merchant and brickmaker and sunk his wealth into lakeside land. Understanding that transportation can raise real-estate values, Milne eagerly sold a slender right-of-way to the railroad company for its track bed. A train station and loading dock were built at the lakefront terminus, to be known as Port Pontchartrain (today’s Elysian Fields Avenue, from Leon C. -

Faubourg Marigny Final

LIVING WITH HISTORY IN NEW ORLEANS’ NEIGHBORHOODS FFaauubboouurrgg Feelings Café nnyy “They told me to take a streetcar named Desire, aarriigg 1721 French engineers plot the Vieux Carré and then transfer to one called Cemeteries and MM 1743 Claude Joseph Villars Dubreuil ride six blocks and get off at—Elysian Fields.” acquires plantation below present- day Esplanade Ave. Blanche Dubois 1798 Pierre Philippe de Marigny acquires “A Streetcar Named Desire” eople in Faubourg Marigny are passionate about plantation 1800 Philippe de Marigny de Mandeville preservation. They saw their downtown neighborhood, inherits father’s estate, including developed as New Orleans’ second suburb in 1806, present-day Faubourg Marigny, abandoned by city officials and desecrated by “modern” making him one of richest people in zoning regulations in the 1950s and ‘60s. Building by New World P 1803 Louisiana Purchase building, they fought to save their historic neighborhood. 1806 Nicholas de Finiels develops street Based on a Tulane University study of the merits of zoning plan for Marigny; engineer Barthelemy as an alternative to historic districting led by Marigny res- Lafon lays out street grid ident, architect and professor Eugene Cizek, the City 1812 Former town common, now Esplanade Ave., subdivided into lots Council adopted Historic 1831 Pontchartrain Railroad (a.k.a. Marigny Zoning in “Smoky Mary”), 2nd oldest railroad 1971. This was the first in U.S., opens on Elysian Fields Ave. historic zoning since the 1832 World’s largest cotton press opens on present-day Press St. Vieux Carré. In 1974 1836 Faubourg Marigny established as these farsighted citizens Third Municipality of the city with won designation for “The separate government Marigny” as a National 1852 Municipalities combine into single city government of New Orleans Published by Register historic district.