The Bellinger Emydura Ecology, Population Status and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Vol. 33, No. 3

1. , F -6 ~.: 1/JJ/im--3'PT* JL* iLLLZW 1- : s . &, , I ' 4% Or *-* 0 4 Z 0 8 of the FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM Biological Sciences Volume 33 1988 Number 3 REPRODUCTIVE STRATEGIES OF SYMPATRIC FRESHWATER EMYDID TURTLES IN NORTHERN PENINSULAR FLORIDA Dale R. Jackson 3-C p . i ... h¢ 4 f .6/ I Se 4 .¢,$ I - - 64». 4 +Ay. 9.H>« UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA GAINESVILLE Numbers of the BULLETIN OF TIIE FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM, BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES, are published at irregular intervals. Volumes contain about 300 pages and,are not necessarily completed in any one calendar year. S. DAVID WEBB, Editor OLIVER L. AUSTIN, JR., Editor Bile,ints RHODA J. BRYANT, Managing Editor Communications concerning purchase or exchange of the publications and all manuscripts should be addressed to: Managing Editor, Bulletin; Florida State Museum; University of Florida; Gainesville FL 32611; U.S.A. This public document was promulgated at an annual cost of $2003.53 or $2.000 per copy. It makes available to libraries, scholars, and all interested persons the results of researches in the natural sciences, emphasizing the circum- Caribbean region. ISSN: 0071-6154 CODEN: BFSBAS Publication date: 8/27 Price: $2.00 REPRODUCTIVE STRATEGIES OF SYMPATRIC FRESHWATER EMYDID TURTLES IN NORTHERN PENINSULAR FLORIDA Dale R. Jackson Frontispiece. Alligator nest on Payne's Prairie, Alachua County, Florida, opened to expose seven clutches of Psmdenzys nelsoni eggs and one clutch of Trioi,br ferox eggs (far lower right) surrounding the central clutch of alligator eggs. Most of the alligator eggs had been destroyed earlier by raccoons. REPRODUCTIVE STRATEGIES OF SYMPATRIC FRESHWATER EMYDID TURTLES IN NORTHERN PENINSULAR FLORIDA Dale R. -

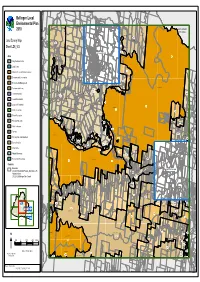

LEP 2010 LZN Template

WILD CATTLE CREEK E1E1E1 DORRIGO RU2RU2 GLENREAGH MULDIVA RU2RU2 OLD BILLINGS RD RAILWAY NATURE COAST TYRINGHAM RESERVE RD RD Bellingen Local E1EE1E11 BORRA CREEK DORRIGO NATIONAL PARK CORAMBA RD E3EE3E33 SLINGSBYS Environmental Plan LITTLE MURRAY RIVER RU2RRU2U2 RD LITTLE PLAIN CREEK BORRA CREEK TYRINGHAM COFFSCOFFS HARBOURHARBOUR 2010 RD CITYCCITYITY COUNCILCOUNCIL BREAKWELLS WILD CATTLE CREEK RD RU2RRU2U2 CORAMBA RD RU2RU2 NEAVES NEAVES RD RD SLINGSBYS RD Land Zoning Map LITTLE MURRAY RIVER OLD COAST RD E3EE3E33 RU2RRU2U2 Sheet LZN_004 E3EE3E33 DEER VALE RD OLD CORAMBA TYRINGHAM RD NTH RD ROCKY CREEK RU1RU1 BARTLETTS RD ReferRefer toto mapmap LZN_004ALZN_004A Zone RU1RRU1U1 BIELSDOWN RIVER E1EE1E11 DEER VALE RD B1 Neighbourhood Centre RU1RU1 DORRIGO NATIONAL PARK B2 Local Centre JOHNSENS WATERFALL WAY OLD CORAMBA WATERFALL WAY RD STH EE3E3E33 E1 National Parks and Nature Reserves E3E3E3 BENNETTS RD E2 Environmental Conservation WATERFALL WAY SHEPHERDS RD RU1RRU1U1 E3 Environmental Management DOME RD EVERINGHAMS ROCKY CREEK RD BIELSDOWN RIVER DORRIGO NATIONAL PARK E4 Environmental Living E3EE3E33 SP1SP1SP1 E3E3E3 SHEPHERDS RD WHISKY CEMETERYCCEMETERYEMETERY DOME RD IN1 General Industrial CREEK RD RU1RRU1U1 RU1RRU1U1 WOODLANDS RD WATERFALL R1 General Residential WAY RU1RRU1U1 PROMISED RU1RU1 E3E3E3 LAND RD WATERFALL WAY R5 Large Lot Residential WHISKY CREEK E1EE1E11 RU1RU1 DORRIGO NATIONAL PARK E1E1E1 E1EE1E11 RE1 Public Recreation BIELSDOWN RIVER E3EE3E33 ROCKY CREEK RD RE2 Private Recreation WHISKY CREEK RD RU1RRU1U1 RU2RU2 E3E3E3 -

Demographic Consequences of Superabundance in Krefft's River

i The comparative ecology of Krefft’s River Turtle Emydura krefftii in Tropical North Queensland. By Dane F. Trembath B.Sc. (Zoology) Applied Ecology Research Group University of Canberra ACT, 2601 Australia A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Applied Science (Resource Management). August 2005. ii Abstract An ecological study was undertaken on four populations of Krefft’s River Turtle Emydura krefftii inhabiting the Townsville Area of Tropical North Queensland. Two sites were located in the Ross River, which runs through the urban areas of Townsville, and two sites were in rural areas at Alligator Creek and Stuart Creek (known as the Townsville Creeks). Earlier studies of the populations in Ross River had determined that the turtles existed at an exceptionally high density, that is, they were superabundant, and so the Townsville Creek sites were chosen as low abundance sites for comparison. The first aim of this study was to determine if there had been any demographic consequences caused by the abundance of turtle populations of the Ross River. Secondly, the project aimed to determine if the impoundments in the Ross River had affected the freshwater turtle fauna. Specifically this study aimed to determine if there were any difference between the growth, size at maturity, sexual dimorphism, size distribution, and diet of Emydura krefftii inhabiting two very different populations. A mark-recapture program estimated the turtle population sizes at between 490 and 5350 turtles per hectare. Most populations exhibited a predominant female sex-bias over the sampling period. Growth rates were rapid in juveniles but slowed once sexual maturity was attained; in males, growth basically stopped at maturity, but in females, growth continued post-maturity, although at a slower rate. -

Bellinger and Kalang River Estuaries Erosion Study

Bellinger and Kalang River Estuaries Erosion Study Damon Telfer GECO Environmental Tim Cohen IRM Consultants February 2010 Report prep ared for BELLINGEN SHIRE COUNCIL DISCLAIMER Whilst every care has been taken in compiling this erosion study and report, no assurances are given that it is free from error or omission. The authors make no expressed or implied warranty of the accuracy or fitness of the recommendations in the report and disclaim all liability for the consequences of anything done or omitted to be done by any person in reliance upon these recommendations. The use of this report is at the user’s risk and discretion. The authors will not be liable for any loss, damage, costs or injury including consequential, incidental, or financial loss arising out of the use of this report. This report was produced with financial assistance from the NSW Government through the Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water. This document does not necessarily represent the opinions of the NSW Government or the Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water. Damon Telfer GECO Environmental 5 Arcadia Lane, GRASSY HEAD NSW 2441 Email: [email protected] © Damon Telfer, February 2010. This document is copyright and cannot be reproduced in part or whole without the express permission of the author. A permanent, irrevocable royalty-free, non-exclusive license to make these reports, documents and any other materials publicly available and to otherwise communicate, reproduce, adapt and publicise them on a non- profit basis is granted by the authors to Bellingen Shire Council and the Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water. -

Eastern Snake-Necked Turtle

Husbandry Manual for Eastern Snake-Necked Turtle Chelodina longicollis Reptilia: Chelidae Image Courtesy of Jacki Salkeld Author: Brendan Mark Host Date of Preparation: 04/06/06 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE - Richmond Course Name and Number: 1068 Certificate 3 - Captive Animals Lecturers: Graeme Phipps/Andrew Titmuss/ Jacki Salkeld CONTENTS 1. Introduction 4 2. Taxonomy 5 2.1 Nomenclature 5 2.2 Subspecies 5 2.3 Synonyms 5 2.4 Other Common Names 5 3. Natural History 6 3.1 Morphometrics 6 3.1.1 Mass and Basic Body Measurements 6 3.1.2 Sexual Dimorphism 6 3.1.3 Distinguishing Features 7 3.2 Distribution and Habitat 7 3.3 Conservation Status 8 3.4 Diet in the Wild 8 3.5 Longevity 8 3.5.1 In the Wild 8 3.5.2 In Captivity 8 3.5.3 Techniques Used to Determine Age in Adults 9 4. Housing Requirements 10 4.1 Exhibit/Enclosure Design 10 4.2 Holding Area Design 10 4.3 Spatial Requirements 11 4.4 Position of Enclosures 11 4.5 Weather Protection 11 4.6 Temperature Requirements 12 4.7 Substrate 12 4.8 Nestboxes and/or Bedding Material 12 4.9 Enclosure Furnishings 12 5. General Husbandry 13 5.1 Hygiene and Cleaning 13 5.2 Record Keeping 13 5.3 Methods of Identification 13 5.4 Routine Data Collection 13 6. Feeding Requirements 14 6.1 Captive Diet 14 6.2 Supplements 15 6.3 Presentation of Food 15 1 7. Handling and Transport 16 7.1 Timing of Capture and Handling 16 7.2 Capture and Restraint Techniques 16 7.3 Weighing and Examination 17 7.4 Release 17 7.5 Transport Requirements 18 7.5.1 Box Design 18 7.5.2 Furnishings 19 7.5.3 Water and Food 19 7.5.4 Animals Per Box 19 7.5.5 Timing of Transportation 19 7.5.6 Release from Box 19 8. -

Recent Evolutionary History of the Australian Freshwater Turtles Chelodina Expansa and Chelodina Longicollis

Recent evolutionary history of the Australian freshwater turtles Chelodina expansa and Chelodina longicollis. by Kate Meredith Hodges B.Sc. (Hons) ANU, 2004 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences Department of Genetics and Evolution The University of Adelaide December, 2015 Kate Hodges with Chelodina (Macrochelodina) expansa from upper River Murray. Photo by David Thorpe, Border Mail. i Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. The author acknowledges that copyright of published works contained within this thesis resides with the copyright holder(s) of those works. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University’s digital research repository, the Library catalogue and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. -

Status Review, Disease Risk Analysis and Conservation Action Plan for The

Status Review, Disease Risk Analysis and Conservation Action Plan for the Bellinger River Snapping Turtle (Myuchelys georgesi) December, 2016 1 Workshop participants. Back row (l to r): Ricky Spencer, Bruce Chessman, Kristen Petrov, Caroline Lees, Gerald Kuchling, Jane Hall, Gerry McGilvray, Shane Ruming, Karrie Rose, Larry Vogelnest, Arthur Georges; Front row (l to r) Michael McFadden, Adam Skidmore, Sam Gilchrist, Bruno Ferronato, Richard Jakob-Hoff © Copyright 2017 CBSG IUCN encourages meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believes that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and views expressed by the authors may not necessarily reflect the formal policies of IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Jakob-Hoff, R. Lees C. M., McGilvray G, Ruming S, Chessman B, Gilchrist S, Rose K, Spencer R, Hall J (Eds) (2017). Status Review, Disease Risk Analysis and Conservation Action Plan for the Bellinger River Snapping Turtle. IUCN SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Cover photo: Juvenile Bellinger River Snapping Turtle © 2016 Brett Vercoe This report can be downloaded from the CBSG website: www.cbsg.org. 2 Executive Summary The Bellinger River Snapping Turtle (BRST) (Myuchelys georgesi) is a freshwater turtle endemic to a 60 km stretch of the Bellinger River, and possibly a portion of the nearby Kalang River in coastal north eastern New South Wales (NSW). -

NSW Police Gazette 1878

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently This sampler file includes the title page and various sample pages from this volume. This file is fully searchable (read search tips page) but is not FASTFIND enabled New South Wales Police Gazette 1878 Ref. AU2103-1878 ISBN: 978 1 921416 10 1 This book was kindly loaned to Archive CD Books Australia by New South Wales Justice and Police Museum http://www.hht.net.au/museums/jp/justice_and_police_museum Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

Effects of Estuarine Acidification on Survival and Growth of the Sydney Rock Oyster Saccostrea Glomerata

EFFECTS OF ESTUARINE ACIDIFICATION ON SURVIVAL AND GROWTH OF THE SYDNEY ROCK OYSTER SACCOSTREA GLOMERATA Michael Colin Dove Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The University of New South Wales Geography Program Faculty of the Built Environment The University of New South Wales Sydney, NSW, 2052 April 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Jes Sammut for his ideas, guidance and encouragement throughout my candidature. I am indebted to Jes for his help with all stages of this thesis, for providing me with opportunities to present this research at conferences and for his friendship. I thank Dr Richard Callinan for his assistance with the histopathology and reviewing chapters of this thesis. I am also very grateful to Laurie Lardner and Ian and Rose Crisp for their invaluable advice, generosity and particular interest in this work. Hastings and Manning River oyster growers were supportive of this research. In particular, I would like to acknowledge the following oyster growers: Laurie and Fay Lardner; Ian and Rose Crisp; Robert Herbert; Nathan Herbert; Stuart Bale; Gary Ruprecht; Peter Clift; Mark Bulley; Chris Bulley; Bruce Fairhall; Neil Ellis; and, Paul Wilson. I am very grateful to Holiday Coast Oysters and Manning River Rock Oysters for providing: the Sydney rock oysters for field and laboratory experiments; storage facilities; equipment; materials; fuel; and, access to resources without reservation. Bruce Fairhall, Paul Wilson, Mark Bulley, Laurie Lardner and Robert Herbert also supplied Sydney rock oysters for this work. I would also like to thank the researchers who gave helpful advice during this study. -

Transport for NSW Mid-North Coast Regional Boating Plan

Transport for NSW Regional Boating Plan Mid-North Coast Region February 2015 Transport for NSW 18 Lee Street Chippendale NSW 2008 Postal address: PO Box K659 Haymarket NSW 1240 Internet: www.transport.nsw.gov.au Email: [email protected] ISBN Register: 978 -1 -922030 -68 -9 © COPYRIGHT STATE OF NSW THROUGH THESECRETARY OF TRANSPORT FOR NSW 2014 Extracts from this publication may be reproduced provided the source is fully acknowledged. Report for Transport for NSW - Regional Boating Plan| i Table of contents 1. Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Physical character of the waterways .............................................................................................. 6 2.1 Background .......................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Bellinger and Nambucca catchments and Coffs Harbour area ........................................... 7 2.3 Macleay catchment .............................................................................................................. 9 2.4 Hastings catchment ............................................................................................................. 9 2.5 Lord Howe Island ............................................................................................................... 11 2.6 Inland waterways .............................................................................................................. -

AUSTRALIAN BIODIVERSITY RECORD ______2007 (No 2) ISSN 1325-2992 March, 2007 ______

AUSTRALIAN BIODIVERSITY RECORD ______________________________________________________________ 2007 (No 2) ISSN 1325-2992 March, 2007 ______________________________________________________________ Some Taxonomic and Nomenclatural Considerations on the Class Reptilia in Australia. Some Comments on the Elseya dentata (Gray, 1863) complex with Redescriptions of the Johnstone River Snapping Turtle, Elseya stirlingi Wells and Wellington, 1985 and the Alligator Rivers Snapping Turtle, Elseya jukesi Wells 2002. by Richard W. Wells P.O. Box 826, Lismore, New South Wales Australia, 2480 Introduction As a prelude to further work on the Chelidae of Australia, the following considerations relate to the Elseya dentata species complex. See also Wells and Wellington (1984, 1985) and Wells (2002 a, b; 2007 a, b.). Elseya Gray, 1867 1867 Elseya Gray, Ann. Mag. Natur. Hist., (3) 20: 44. – Subsequently designated type species (Lindholm 1929): Elseya dentata (Gray, 1863). Note: The genus Elseya is herein considered to comprise only those species with a very wide mandibular symphysis and a distinct median alveolar ridge on the upper jaw. All members of the latisternum complex lack a distinct median alveolar ridge on the upper jaw and so are removed from the genus Elseya (see Wells, 2007b). This now restricts the genus to the following Australian species: Elseya albagula Thomson, Georges and Limpus, 2006 2006 Elseya albagula Thomson, Georges and Limpus, Chelon. Conserv. Biol., 5: 75; figs 1-2, 4 (top), 5a,6a, 7. – Type locality: Ned Churchwood Weir (25°03'S 152°05'E), Burnett River, Queensland, Australia. Elseya dentata (Gray, 1863) 1863 Chelymys dentata Gray, Ann. Mag. Natur. Hist., (3) 12: 98. – Type locality: Beagle’s Valley, upper Victoria River, Northern Territory. -

REPTILIA: TESTUDINES: PODOCNEMIDIDAE Podocnemis Unifilis

890.1 REPTILIA: TESTUDINES: PODOCNEMIDIDAE Podocnemis unifilis Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Schneider, L., J.B. Iverson, and R.C. Vogt. 2012. Podocnemis unifilis . Podocnemis unifilis Troschel 1848 Yellow-spotted River Turtle, Tracajá. Emys cayennensis Schweigger 1812:298. Type-lo- cality, “Cayenna” [= Cayenne]. Holotype not des - ignated but three syntypes are mentioned. Lec- totype, Paris Museum of Natural History (MNHN) 8359 (see Pritchard and Trebbau 1984 and Bour 2006 for justification), a juvenile dry specimen (head and shell separated), collected by L.C.M. Richard between 1781 and 1789 (not examined by authors). See Remarks . Testudo terekay : Humboldt and Bonpland 1819:482. Ch[elys]. (Hydraspis) Lata: Bell in Gray 1831a:17 ( no- men oblitum ) ( see Rhodin et al. 2008) . Ch[elys]. (Hydraspis) Cayennensis : Gray 1831a:17. Hydraspis Cayennensis : Gray 1831b:42. Emys Terekay Schinz 1833:41. Type-locality, “obern Orenoko [= upper Rio Orinoco] wie unterden Cataracten, und sogar auch im [Rio] Apure, im [Rio] Uritucu, im [Rio] Guarico und den kleinern Flüssen, welche die Llannos von Caracas durch - strömmen,” Venezuela. Holotype not located. Podocnemis dumeriliana : Duméril and Bibron 1835: 387 (part). Podocnemis unifilis Troschel 1848:647. Type-locality, “Rupununi und Takutu”, Guyana. Syntypes, Zoo- logische Museum Berlin (ZMB) 142 (2 specimens in alcohol), collected by R. Schomburgk, date unknown (not examined by authors, but existence confirmed by Fritz et al. 1994a). Podocnemis tracaya Coutinho 1868:149. Type-locali - ty, “Amazone.” Chelonemys dumeriliana : Gray 1870:83 (part). Podocnemis cayennensis : Siebenrock 1902:162 (part). Podocnemys unifilis : Shah 1961:215. Lapsus. Podocnemis unifillis : Zendzian and Barnard 1967: FIGURE 1. Podocnemis unifilis : Adult female (top), adult male (center), and hatchling (bottom).