The Conservative Party Human Rights Commission Annual Report 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unity, Vision and Brexit

1 ‘Brexit means Brexit’: Theresa May and post-referendum British politics Nicholas Allen Department of Politics and International Relations Royal Holloway, University of London Surrey, TW20 0EX [email protected] Abstract: Theresa May became prime minister in July 2016 as a direct result of the Brexit referendum. This article examines her political inheritance and leadership in the immediate wake of the vote. It analyses the factors that led to her victory in the ensuing Tory leadership contest and explores both the main challenges that confronted her and the main features of her response to them. During his first nine months in office, May gave effect to the referendum, defined Brexit as entailing Britain’s removal from membership of the European Union’s single market and customs union and sought to reposition her party. However, her failure to secure a majority in the 2017 general election gravely weakened her authority and the viability of her plans. At time of writing, it is unclear how much longer her premiership can last or if she will be able to exercise effective leadership over Brexit. Keywords: Theresa May; Brexit; prime ministers; leadership; Conservative party This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of an article published in British Politics. The definitive publisher-authenticated version, Nicholas Allen (2017) ‘‘Brexit means Brexit’: Theresa May and post-referendum British politics’, British Politics, First Online: 30 November, doi.org/10.1057/s41293-017-0067-3 is available online at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41293-017-0067-3 2 Introduction According to an old university friend, Theresa May had once wanted to be Britain’s first female prime minister (Weaver, 2016). -

Westminster Hall PDF File 0.05 MB

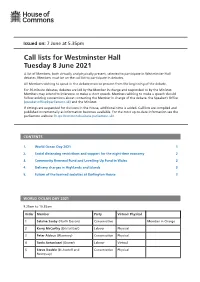

Issued on: 7 June at 5.35pm Call lists for Westminster Hall Tuesday 8 June 2021 A list of Members, both virtually and physically present, selected to participate in Westminster Hall debates. Members must be on the call list to participate in debates. All Members wishing to speak in the debate must be present from the beginning of the debate. For 30-minute debates, debates are led by the Member in charge and responded to by the Minister. Members may attend to intervene or make a short speech. Members wishing to make a speech should follow existing conventions about contacting the Member in charge of the debate, the Speaker’s Office ([email protected]) and the Minister. If sittings are suspended for divisions in the House, additional time is added. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to-date information see the parliament website: https://commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. World Ocean Day 2021 1 2. Social distancing restrictions and support for the night-time economy 2 3. Community Renewal Fund and Levelling Up Fund in Wales 2 4. Delivery charges in Highlands and Islands 3 5. Future of the learned societies at Burlington House 3 WORLD OCEAN DAY 2021 9.25am to 10.55am Order Member Party Virtual/ Physical 1 Selaine Saxby (North Devon) Conservative Member in Charge 2 Kerry McCarthy (Bristol East) Labour Physical 3 Peter Aldous (Waveney) Conservative Physical 4 Tonia Antoniazzi (Gower) Labour Virtual 5 Steve Double (St Austell and Conservative Physical Newquay) -

Catholic Social Teaching: Sharing the Secret…

Catholic Social Teaching: Sharing the Secret… 1 September 2021 Volume 2, Number 9 In This Issue • Upcoming Events Tory MP Says ‘Some People Don't Need an Extra • Tory MP Says ‘Some People Don’t £20' Need An Extra £20’ No, he’s not talking about millionaires and billionaires, or even people who are in comfortable circumstances---Tory backbencher Andrew Rosindell has • Week of Action Sponsored by Stop argued that the extra £20 in Universal Credit brought in during the the Arms Fair coronavirus pandemic should be scrapped, saying “I think there are people • Forgiving Reality and Forgiving that quite like getting the extra £20 but maybe they don't need it.” Ourselves In contrast, Labour’s Carolyn Harris hit back, saying the £20 would be taken • Love, Justice and the Common Good away from “people who can least afford to lose it”. She added: “£20 is food • The Poor Evangelise Us for a week. £20 is a lifeline for people on Universal Credit.” Other Conservative party members also urged Chancellor Rishi Sunak to make the increase permanent. Former Tory leader and instigator of UPCOMING EVENTS Universal Credit Sir Iain Duncan Smith, along with five of his successors – Stephen Crabb, Damian Green, David Gauke, Esther McVey and Amber 1 September: World Day of Prayer for Rudd – have written to Sunak in an effort to persuade him to stick with the Season of Creation £5 billion benefits investment. 2-8 September: Week of Action to Sir Ian warned that a failure to keep the £20 uplift in place permanently protest the DSEI Arms Fair (see would “damage living standards, health and opportunities” for those that accompanying article in this issue). -

EU Referendum 2016 V7

EU Referendum 2016 Three Scenarios for the Government An insights and analysis briefing from The Whitehouse Consultancy Issues-led communications 020 7463 0690 [email protected] whitehouseconsulting.co.uk The EU Referendum The EU referendum has generated an unparalleled level of political If we vote to leave, a new Prime Minister will likely emerge from among debate in the UK, the result of which is still too close to call. Although the 'Leave' campaigners. What is questionable is whether Mr Cameron we cannot make any certain predictions, this document draws upon will stay in position to deal with the immediate questions posed by Whitehouse’s political expertise and media analysis to suggest what Brexit: such as the timetable for withdrawal, or how trading and may happen to the Government’s composition in the event of: diplomatic relations will proceed. Will he remain at Number 10, perhaps • A strong vote to remain (by 8% or more); until a party conference in the autumn, or will there be more than one new beginning? • A weak vote in favour of remaining (by up to 8%); or • A vote to leave. “The result could create If the UK chooses to remain by a wide margin, the subsequent reshue will aord an opportunity to repair the Conservative Party after a a new political reality.” bruising campaign period. This result will prompt a flurry of It is clear that the referendum result could create a new political reality on parliamentary activity, renewing the Prime Minister’s mandate until he 24 June. Businesses must be prepared to engage if they are to mitigate the stands down closer to 2020 and enable a continuation of the impacts and take advantage of the opportunities presented. -

Ministers' Gifts

Wales Office – Quarterly Ministerial Transparency Return MINISTERS’ GIFTS (GIVEN AND RECEIVED) GIFTS GIVEN OVER £140 Rt. Hon David Jones MP, Secretary of State for Wales Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Stephen Crabb MP, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Baroness Randerson, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Nil Return GIFTS RECEIVED OVER £140 Rt. Hon David Jones MP, Secretary of State for Wales Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Retained by the Department/ Purchased by the Minister/ Used for official entertainment Stephen Crabb MP, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Retained by the Department/ Purchased by the Minister/ Used for official entertainment Wales Office – Quarterly Ministerial Transparency Return Baroness Randerson, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Nil return Retained by the Department/ Purchased by the Minister/ Used for official entertainment Wales Office – Quarterly Ministerial Transparency Return MINISTERS’ HOSPITALITY HOSPITALITY RECEIVED Rt. Hon David Jones MP, Secretary of State for Wales Date of Name of organisation - Type of hospitality received hospitality 4 October Fast Growth 50 Dinner 10 October EADS Lunch & Canapes 11 October European Space Agency Lunch Stephen Crabb MP, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date of Name of organisation - Type of hospitality -

Read the Report

Will HUTTON Sir Malcolm RIFKIND Con COUGHLIN Peter TATCHELL Does West know best? bright blue AUTUMN 2011 flickr.com/familymwr Contributors Matt Cavanagh is the Associate Director for UK Migration Policy at the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) Con Coughlin is the Executive Foreign Editor of The Daily Telegraph Sir Malcolm Rifkind MP Brendan Cox is the Director of Policy and Advocacy at Save the Children Stephen Crabb MP is MP for Preseli Pembrokeshire and Leader of Project Umubano, the Conservatives’ social action project in Rwanda and Sierra Leone Richard Dowden is Director of the Royal African Society and author of Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles Maurice Fraser is a Senior Fellow in European Politics at the London School of Economics (LSE) and an Associate Fellow at Chatham House Peter Tatchell Will Hutton is a columnist for The Observer , executive vice-chair of The Work Foundation and Principal of Hertford College, Oxford University Professor Eric Kaufmann is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck College, University of London, the author of Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth and was a Visiting Fellow at the Kennedy School, Harvard in 2008-9. Sir Malcolm Rifkind MP is MP for Kensington and was Foreign Secretary, 1995-7 Victoria Roberts is Deputy Chairman of the Tory Reform Group Will Hutton Henneke Sharif is an Associate at Counterpoint and a Board Member of Bright Blue Guy Stagg is the Online Lifestyle Editor for The Daily Telegraph Peter Tatchell is a human rights campaigner Garvan Walshe is the Publications Director -

2014 Cabinet Reshuffle

2014 Cabinet Reshuffle Overview A War Cabinet? Speculation and rumours have been rife over Liberal Democrat frontbench team at the the previous few months with talk that the present time. The question remains if the Prime Minister may undertake a wide scale Prime Minister wishes to use his new look Conservative reshuffle in the lead up to the Cabinet to promote the Government’s record General Election. Today that speculation was in this past Parliament and use the new talent confirmed. as frontline campaigners in the next few months. Surprisingly this reshuffle was far more extensive than many would have guessed with "This is very much a reshuffle based on the Michael Gove MP becoming Chief Whip and upcoming election. Out with the old, in William Hague MP standing down as Foreign with the new; an attempt to emphasise Secretary to become Leader of the House of diversity and put a few more Eurosceptic Commons. Women have also been promoted faces to the fore.” to the new Cameron Cabinet, although not to the extent that the media suggested. Liz Truss Dr Matthew Ashton, politics lecturer- MP and Nicky Morgan MP have both been Nottingham Trent University promoted to Secretary of State for Environment and Education respectively, whilst Esther McVey MP will now attend Europe Cabinet in her current role as Minister for Employment. Many other women have been Surprisingly Lord Hill, Leader for the promoted to junior ministry roles including Conservatives in the House of Lords, has been Priti Patel MP to the Treasury, Amber Rudd chosen as the Prime Minister’s nomination for MP to DECC and Claire Perry MP to European Commissioner in the new Junker led Transport, amongst others. -

Formal Minutes

House of Commons Liaison Committee Formal Minutes Session 2019–21 Liaison Committee: Formal Minutes 2019–21 1 Formal Minutes of the Liaison Committee, Session 2019–21 1. THURSDAY 21 MAY 2020 Virtual meeting Members present: Sir Bernard Jenkin, in the Chair Hilary Benn Andrew Jones Mr Clive Betts Darren Jones Karen Bradley Julian Knight Chris Bryant Angus Brendan MacNeil Sir William Cash Sir Robert Neill Sarah Champion Caroline Nokes Greg Clark Neil Parish Stephen Crabb Mel Stride Tobias Ellwood Stephen Timms Lilian Greenwood Tom Tugendhat Robert Halfon Bill Wiggin Meg Hillier Pete Wishart Simon Hoare William Wragg Jeremy Hunt 1. Declarations of Interests Members declared their interests, in accordance with the Resolution of the House of 13 July 1992 (see Appendix). 2. Committee working practices and future programme Resolved, That Hilary Benn, Karen Bradley, Sarah Champion, Greg Clark and Pete Wishart be members of an informal Working Group to support the Chair with delegated duties and decision making between formal committee meetings. Resolved, That witnesses should be heard in public, unless the Committee otherwise ordered. Resolved, That witnesses who submit written evidence to the Committee are authorised to publish it on their own account in accordance with Standing Order No. 135, subject always to the discretion of the Chair or where the Committee otherwise orders. Resolved, That the Committee shall not normally examine individual cases. Resolved, That the Chair have discretion to: 2 Liaison Committee: Formal Minutes 2017–19 (a) -

Correspondence Between Select Committee Chairs and the Minister

House of Commons Committee Office, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA Chloe Smith MP Minister of State for the Constitution and Devolution Cabinet Office 70 Whitehall London SW1A 2AS 19 October 2020 Dear Chloe, In June you sent correspondence1 outlining proposed arrangements for the parliamentary scrutiny of UK common frameworks. As the Chairs of Select Committees with an interest in scrutinising these frameworks, we wish to comment on the Government’s proposals and how they could be strengthened to ensure Parliament has sufficient time to analyse frameworks and conduct scrutiny with maximum transparency. We are encouraged by the Government’s commitment to share framework summaries with committees ahead of a provisional framework. This will allow Committee Members and officials to become acquainted with the issues and determine how they will approach the provisional framework. While we appreciate the commitment made to the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee (PACAC) to share these a month before scrutiny begins, it is important that the summary framework is shared a month before the JMC (EN) meets so that Committees can feed into the JMC (EN) process.2 This will make it more likely that frameworks can receive swift scrutiny once the provisional frameworks are laid. We are also disappointed that some departments have instructed committees not to publish summaries. While we appreciate these documents are intended to inform future parliamentary scrutiny when the policy content of a framework is more comprehensively developed, publishing them would allow committees to engage with external stakeholders in advance and identify topics to focus on upon receiving the provisional framework. -

List of Ministers' Interests

LIST OF MINISTERS’ INTERESTS CABINET OFFICE DECEMBER 2015 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Prime Minister 3 Attorney General’s Office 5 Department for Business, Innovation and Skills 6 Cabinet Office 8 Department for Communities and Local Government 10 Department for Culture, Media and Sport 12 Ministry of Defence 14 Department for Education 16 Department of Energy and Climate Change 18 Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs 19 Foreign and Commonwealth Office 20 Department of Health 22 Home Office 24 Department for International Development 26 Ministry of Justice 27 Northern Ireland Office 30 Office of the Advocate General for Scotland 31 Office of the Leader of the House of Commons 32 Office of the Leader of the House of Lords 33 Scotland Office 34 Department for Transport 35 HM Treasury 37 Wales Office 39 Department for Work and Pensions 40 Government Whips – Commons 42 Government Whips – Lords 46 INTRODUCTION Ministerial Code Under the terms of the Ministerial Code, Ministers must ensure that no conflict arises, or could reasonably be perceived to arise, between their Ministerial position and their private interests, financial or otherwise. On appointment to each new office, Ministers must provide their Permanent Secretary with a list in writing of all relevant interests known to them which might be thought to give rise to a conflict. Individual declarations, and a note of any action taken in respect of individual interests, are then passed to the Cabinet Office Propriety and Ethics team and the Independent Adviser on Ministers’ Interests to confirm they are content with the action taken or to provide further advice as appropriate. -

House of Commons Wednesday 13 July 2011 Votes and Proceedings

No. 186 1245 House of Commons Wednesday 13 July 2011 Votes and Proceedings The House met at 11.30 am. PRAYERS. 1 Private Bills [Lords]: London Local Authorities and Transport for London (No. 2) Bill [Lords]: Second Reading Motion made, That the London Local Authorities and Transport for London (No. 2) Bill [Lords] be now read a second time. Objection taken (Standing Order No. 20(2)). Bill to be read a second time on Tuesday 6 September. 2 Mull of Kintyre Review Resolved, That an Humble Address be presented to Her Majesty, That she will be graciously pleased to give directions that there be laid before this House a Return of the Report, dated 13 July 2011, of the Mull of Kintyre Review: An independent Review to examine all available evidence relating to the findings of the Board of Inquiry into the fatal accident at the Mull of Kintyre on 2 June 1994.—(Miss Chloe Smith.) 3 Contingencies Fund 2010–11 Ordered, That there be laid before this House an Account of the Contingencies Fund, 2010– 11, showing— (1) a Statement of Financial Position; (2) a Statement of Cash Flows; and (3) Notes to the Account; together with the Certificate and Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General thereon.—(Miss Chloe Smith.) 4 Questions to (1) the Secretary of State for International Development (2) the Prime Minister 5 Statements: (1) Phone hacking (The Prime Minister) (2) Mull of Kintyre Review (Secretary Liam Fox) 6 Youth Employment: Motion for leave to bring in a Bill (Standing Order No. 23) Motion made and Question proposed, That leave be given to bring -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Monday Volume 613 11 July 2016 No. 23 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 11 July 2016 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2016 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON.DAVID CAMERON, MP, MAY 2015) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. David Cameron, MP FIRST SECRETARY OF STATE AND CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. George Osborne, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Michael Fallon, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. Michael Gove, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,INNOVATION AND SKILLS AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Stephen Crabb, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH—The Rt Hon. Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Nicky Morgan, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT—The Rt Hon. Justine Greening, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR TRANSPORT—The Rt Hon.