Reproductive Technologies and Surrogacy: a Feminist Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files The R&B Pioneers Series edited by Claus Röhnisch from August 2019 – on with special thanks to Thomas Jarlvik The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 1) John Lee Hooker Part II There are 12 books (plus a Part II-book on Hooker) in the R&B Pioneers Series. They are titled The Great R&B Files at http://www.rhythm-and- blues.info/ covering the history of Rhythm & Blues in its classic era (1940s, especially 1950s, and through to the 1960s). I myself have used the ”new covers” shown here for printouts on all volumes. If you prefer prints of the series, you only have to printout once, since the updates, amendments, corrections, and supplementary information, starting from August 2019, are published in this special extra volume, titled ”Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files” (book #13). The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 2) The R&B Pioneer Series / CONTENTS / Updates & Amendments page 01 Top Rhythm & Blues Records – Hits from 30 Classic Years of R&B 6 02 The John Lee Hooker Session Discography 10 02B The World’s Greatest Blues Singer – John Lee Hooker 13 03 Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters 17 04 The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll: The Coasters 18 05 The Blues Giants of the 1950s – Twelve Great Legends 28 06 THE Top Ten Vocal Groups of the Golden ’50s – Rhythm & Blues Harmony 48 07 Ten Sepia Super Stars of Rock ’n’ Roll – Idols Making Music History 62 08 Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons 66 09 The True R&B Pioneers – Twelve Hit-Makers from the -

Big Al's R&B, 1956-1959

The R & B Book S7 The greatest single event affecting the integration of rhythm and blues music Alone)," the top single of 195S, with crossovers "(YouVe Got! The Magic Touch" with the pop field occurred on November 2, 1355. On that date. Billboard (No. 4), "The Great Pretender" and "My Prayer" (both No. It. and "You'll Never magazine expanded its pop singles chart from thirty to a hundred positions, Never Know" b/w "It Isn't Bight" (No. 14). Their first album "The Platters" naming it "The Top 100." In a business that operates on hype and jive, a chart reached No. 7 on Billboard's album chart. position is "proof of a record's strength. Consequently, a chart appearance, by Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, another of the year's consistent crossover itself, can be a promotional tool With Billboard's expansion to an extra seventy artists, tasted success on their first record "Why Do Fools Fall In Love" (No. 71, positions, seventy extra records each week were documented as "bonifide" hits, then followed with "I Want You To Be My Girl" (No. 17). "I Promise To and 8 & B issues helped fill up a lot of those extra spaces. Remember" (No. 57), and "ABCs Of Love" (No. 77). (Joy & Cee-BMI) Time: 2:14 NOT FOR S»U 45—K8592 If Um.*III WIlhORtnln A» Unl» SIM meant tea M. bibUnfmcl him a> a ronng Bnc«rtal««r to ant alonic la *n«l«y •t*r p«rjform«r. HI* » T«»r. Utcfo WIIII* Araraa ()•• 2m«B alnft-ng Th« WorM** S* AtUX prafautonaiiQ/ for on manr bit p«» throoghoQC ih« ib« SaiMt fonr Tun Faaturing coont^T and he •llhan«h 6. -

BOOK by RICHARD SEARLING Limited Number of Signed Copies Available

ANGLO AMERICAN TEL: 01706 818604 PO BOX 4 , TODMORDEN Email : [email protected] LANCS, OL14 6DA. PayPal: [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Website:www.raresoulvinyl.co.uk SALES LIST #785 – MONDAY 7th DECEMBER 2020 RARE SOUL AUCTION DECEMBER 2020 Auction finishes THURSDAY 10th DECEMBER at 6.00pm (18:00) Welcome to the last rare soul auction of this highly unusual year. A chance to get a Christmas present you really want! Due to the nature of the month, the auction will end on THURSDAY 10th DECEMBER at 6.00pm (18:00 GMT). This is much earlier than a normal monthly auction and we will endeavour to keep you reminded and updated on a daily basis. As usual, only winning bidders are notified and within ONE HOUR of the auction end. Good luck! A big thank you to everyone for your custom and support in this very difficult year, it is greatly appreciated. We would like (Tim, Martin, Tom and Nyarai) to wish you a very MERRY CHRISTMAS and a HAPPY NEW YEAR. Surely, 2021 must be a brighter prospect. MIN. BID DECEMBER RARE SOUL AUCTION A THE VINES HEY HEY GIRLS SUTTER 10 M- 250 Not had a copy of this highly distinctive West Coast group dancer in quite a while, from the stable of labels owned by Lee Silver in Los Angeles. B LITTLE JOHNNY OH HOW I LOVE YOU DORE 754 M- 600 HAMILTON A much rarer disc than is commonly perceived, one we have had no more than 3 or 4 times in 35 years. First played by Richard Searling but then probably popularised by Ginger Taylor. -

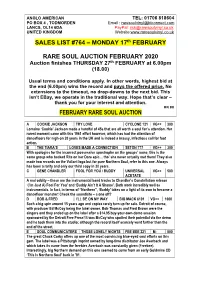

Sales List #764

!"#$%&!'()*+!"&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!,($-&./0.1&2/21.3! 4%&5%6&3&7&,%8'%)8("!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!"#$%&!'!($()*+,&-%./&0123+..)3243+#! $!"+97&%$/3&18!4!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!5$/5$&'!(%360($()*+,&-%./&43+4,6! :"*,(8&;*"#8%'!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!7)1*%2)'8884($()*+,&-%./&43+4,6!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! & 9!$(9&$*9,&<013&=&'%"8!>&/0?@&A(5):!)>& & )!)(&9%:$&!:+,*%"&A(5):!)>&B.B.& !CD?EFG&HEGEI@JI&,K:)98!>&B0?@&A(5):!)>&L?&1M..NO& P/2M..Q& & :ICLR&?JSOI&LGT&DFGTE?EFGI&LNNRUM&*G&F?@JS&VFSTI7&@EW@JI?&XET&L?& ?@J&JGT&P1M..NOQ&VEGI&?@J&SJDFST&LGT&NLUI&?@J&FHHJSJT&NSEDJM&"F& JY?JGIEFGI&?F&?@J&?EOJFC?7&GF&TSFNZTFVGI&?F&?@J&GJY?&XETM&,@EI& EIG[?&(5LU7&VJ&FNJSL?J&EG&?@J&?SLTE?EFGLR&VLUM&KFNJ&?@L?[I&DRJLS&=& ?@LG\&UFC&HFS&UFCS&EG?JSJI?&LGT&L??JG?EFGM&&& & MIN. BID FEBRUARY RARE SOUL AUCTION & A COOKIE JACKSON TRY LOVE CYCLONE 121 VG++ 300 Lorraine ‘Cookie’ Jackson made a handful of 45s that are all worth a soul fan’s attention. Her rarest moment came with this 1961 effort however, which has had the attention of dancefloors for nigh-on 20 years in the UK and is indeed a brassy, infectious call for foot action. B THE TIARA’S LOVES MADE A CONNECTION SETON 777 VG++ 300 With apologies for the incorrect possessive apostrophe on the groups’ name, this is the same group who backed Rita on her Dore epic… tho’ she never actually met them! They also made two records on the Valiant logo but for pure Northern Soul, refer to this one. Always has been a rarity and only our third copy in 30 years. -

Ebony Jo-Ann

Ebony Jo-Ann FILM Grown Ups Mrs. Ronzoni Happy Madison Prods. When in Rome Customer Touchstone Pictures Pootie Tang starring Chris Rock Pootie's Mom Paramount Films Kate & Lepold Nurse Miramax Films Marci X Nurse The Other Brother Mother Pearl The Orphan King Theresa Williams Cosmic Ent./ Ardustry Ent. Eddie starring Whoppi Goldieberg Mrs. Patton Disney/Island Pictures Then I'll be Free Lead Vocals EVT Educ. To Travel Home Title Track Prods., Inc. Charlie Hoboken Secretary Cause & Effect Prods. Fly By Night Aunt Charlotte Fly By Night Prods. Chain of Desires Lady Open Hand Prods. Black Water Police Officer Condor Productions Frederick Douglas: An American Life Harriet Tubman Greaves Productions TELEVISION New York Undercover Knock You Out, Tasha (Episode) Fox Network TV Law & Order 3 Episodes NBC- TV Law & Order: SVU Wrath (Episode) NBC- TV One Life to Live Gospel Choir/ Soloist ABC- TV Clara's Ole Man Big Girl PBS- TV New York News BROADWAY, OFF-BROADWAY & REGIONAL THEATRE Drowning Crow Jackie Biltmore Theatre Crowns Mother Shaw McCarter Theatre (Audelco Award) The Sunshine Boys (Jack Klugman & Tony Randall) Registered Nurse Lyceum Theatre Sheila's Day Ruby Lee Johnson New Victory Theatre Mule Bone Mrs. Blunt Barrymore Theatre Ma Rainey's Black Bottom U.S.- Lead Cort Theatre/ Royale Theatre Do Lord Remember Me (Audelco Award) Music Supervisor/ Ensemble Danny Kaye Theatre Do Lord Remember Me Ensemble American Place Theatre & Town Hall Inacent Black Sally Baby Washington Mitzie Newhouse The Trial of One Short- Sighted Black Woman vs. Mammy Louise New Federal Theatre NYC Mammy Louise NATIONAL TOURS The Wiz Addaperle United States Satchmo Lucille & Mary Armstrong United States Apollo: It Was Just Like Magic Blues Queen N.B.A.F. -

1970-04-04 Article About the Poppy Campus Tour Pages 1-33 and 35

APRIL 4, 1970 $1.00 SEVENTY-SIXTH YEAR The International Music -Record -Tape Newsweekly COIN MACHINE oar PAGES 39 TO 42 Tight Playlist Is '69 Is Seen as Pop Theater New Myth, Poll Charges Top Disk Sales Medium for Acts By CLAUDE HALL By MIKE GROSS NEW YORK-The record in- a Top 40 station of today has 57 Year in Britain NEW YORK - "Pop -Thea- which appeared in the tennis dustry has long claimed that sin- records on its playlist that it ter" is emerging as a new en- scene in Antonioni's film "Blow gles sales were severely hurt by plays. By RICHARD ROBSON tertainment concept for live Up," will be titles "U-Pop the advent of the tight playlist. WTRY in the tri -city area of presentations by rock musicians. Pantomime." The show in- But a Billboard survey of more Albany, Troy, and Schenectady, LONDON - Although fig- It's a format in which the mu- cludes mime, projections and than 100 key Top 40 radio sta- N.Y., publishes a playlist for dis- ures for December have yet to sic is complemented by a thea- original music written by mem- tions coast -to -coast has just re- tribution to the record stores in be published, it looks as though trical production which encom- bers of the Incredible String vealed that the tight playlist is the area of 30 records, plus three 1969 was a record sales year passes pantomime or plot or Band. The music will be re- a myth. One hundred and fifteen records that are picked to be for the British record industry. -

Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXV, No

Institute for Studies In American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXV, No. 1 Fall 2005 “White “The music I’ve been singing, so traditional, it was Woman” as new once. And I’ve been learning to make it mine. But Jazz Collector this! This music is mine in New already!”1 So gushes Miralee Smith, the white Orleans opera singing, jazz-smitten (1947) ingénue played by Dorothy Patrick in the 1947 film New by Orleans, set in 1917. Despite Sherrie Tucker having spent a good deal of the scene talking over the collective improvisation of Louis Armstrong, Kid Ory, Zutty Singleton and other musicians, Miralee finds her attraction to “authentic New Orleans jazz” rising to a Dorothy Patrick, Arturo de Cordova, Louis Armstrong, Billie crescendo. Especially moved Holiday, and other musicians in New Orleans (1947) by the film’s theme song, “Do You Know What it Means to Miss New Orleans,” as sung by Endie, her black maid (played with palpable unhappiness by Billie Holiday in her only role in a feature motion picture), Miralee rises, eyes glowing, cheeks flushed; and declares, “I’m going to sing that New Orleans song!” For this act of white lady impropriety, Miralee is bounced from the Basin Street club. Such a rebuff would crush many a die-hard jazz fan, but not Miralee, whose desire now burns hotter than Buddy Bolden’s trumpet calling the children back home. This music is hers! She simply must feel the song of her black maid moving Inside through her own white lady body, as indeed, she will, before this musical romance is over. -

J2P and P2J Ver 1

SEPTEMBER 14, 1963 SIXTY -NINTH YEAR 50 CENTS PETE SEEGER NIXES OATH; ABC BAN STAYS NEW YORK -ABC Television, which has up till now refused to let outstanding folk singer Pete Seeger appear on the network's weekly "Hootenanny," asked him last week to sign a "loyalty oath affidavit" as a prerequisite for going on the show. Seeger refused. Harold Leventhal, Seeger's manager, accused the network of continuing a blacklisting policy against Seeger and other singers, including the Weavers, whom he also manages. BïlPwa ABC, in effect, admitted that Seeger's political leanings were The International Music -Record Newsweekly behind its refusal to put him on. A network statement confirmed that ABC had sent word to Seeger it would "consider" using him if rn inikitingirTapiagainkiatCoin Machine Operating (Continued on page 6) Coinmen Hold Despite Threat of Bill ,\ Chi Convention Senate Group r Mercury Flies High on Fall Plan' By REN GREVAIT Affirms MOA To Look Into NEW YORK-Mercury Records last week NEW YORK-Mercury execs, in a series of unveiled a special fall plan, "Rally 'Round the high -flying jet flights, covered close to 6,000 Stars," key plank of which is a 10 per cent miles last week in holding three separate sales discount for the next 45 days on new releases meetings, spanning both coasts in five days. Healthy Future SESAC Battle and catalog product. Tradesters were inclined Three regional conventions were held in New (5); (6), Los (9). to call the Mercury program "conservative," and York Chicago and Angeles By AARON STERNFIELD WASHINGTON - SESAC's in line with what appeared in many circles to be Attending all the sessions, which were keyed battle with Southern broadcast- a gradual "firming up" of manufacturer sales to a political convention theme, were President CHICAGO -The Music Op- ers who accuse the licensing policies. -

Rhythm & Blues

RHYTHM & BLUES 65 RHYTHM & BLUES JOHNNY ACE BIG MAYBELLE THE CHRO NO LOG I CAL CD CLASS 5138 € 15.50 THE COMPLETE OKEH & (2005/CLASSICS) 22 tracks 1951-54 8 SESSIONS 1952-55 CD EK 53417 € 11.25 ARTHUR ALEXANDER & (1952-55 ‘OKeh Records’) (73:46/26) Klasse! / superb € Rhythm’n’Soul vocals. THE GREAT EST CD CHD 922 17.75 HALF HEAVEN, HALF Anna- You’re The Reason- Soldier Of Love- I Hang My Head And HEART ACHE CD WESM 589 € 14.90 Cry- You Don’t Care- Dream Girl- Call Me Lone some- After You- & (1962-68 ‘Brunswick’) (68:17/24) Where Have You Been- A Shot Of Rhythm And Blues- Don’t You Know It- You Better Move On- All I Need Is You- Detroit City- Keep OTIS BLACKWELL Her Guess ing- Go Home Girl- In The Middle Of It All- Whole Lot Of THE CHRO NO LOG I CAL VOL.1 CD CLASS 5140 € 15.50 Trou ble- With out A Song- I Wonder Where You Are Tonight- Black TINY BRADSHAW Night THE CHRO NO LOG I CAL CD CLASS 5011 € 15.50 & -The Greatest (1962-65 ‘Dot’) (54:09/21) THE CHRO NO LOG I CAL VOL.2 CD CLASS 5031 € 15.50 LAVERN BAKER THE GREAT COMPOSER CD KING 653 € 15.50 THE CHRO NO LOG I CAL CD CLASS 5126 € 15.50 EP-COLLEC TION...PLUS CD SEE 703 € 18.90 Easy Baby- I Wonder, Baby- Take Out Some Time- I’ll Try (I’ve Tried)- HADDA BROOKS How Long- I want To Rock- Good Daddy- I Want A Laven der Cadil - THAT’S WERE I CAME IN CD CHD 1046 € 17.75 lac- Make It Good- Trying- Pig Latin Blues- Lost Child- Must I Cry Again- You’ll Be Crying- How Can You Leave A Man Like This- Soul BUSTER BROWN On Fire- I’m Living My Life For You- I’m In A Crying Mood- I Can’t RAISE A RUCKUS TONIGHT CD REL 7064 € 15.50 & (1959-62 ‘Fire Records’) (58:15/21) Die kompletteste Hold Out Any Longer- Of Course I Do- Tomor row Night- You Better Zusammenstellung der ‘Fire’-Aufnahmen diese Sängers und Stop- Tweedle Dee Harmonicaspielers, der bestens für sein “Fannie Mae” bekannt & (1949-54) (64:26/23) ist. -

The World of SOUL PRICE: $1 25

BillboardTheSOUL WorldPRICE: of $1 25 Documenting the impact of Blues and R&Bupon ourmusical culture The Great Sound of Soul isonATLANTIC *Aretha Franklin *WilsonPickett Sledge *1°e16::::rifters* Percy *Young Rascals Estherc Phillipsi * Barbara.44Lewis Wi gal Sow B * rBotr ho*ethrserSE:t BUM S010111011 Henry(Dial) Clarence"Frogman" Sweet Inspirations * Benny Latimore (Dade) Ste tti L lBriglit *Pa JuniorWells he Bhiebelles aBel F M 1841 Broadway,ATLANTIC The Great Sound of Soul isonATCO Conley Arthur *KingCurtis * Jimmy Hughes (Fame) *BellE Mg DeOniaCkS" MaryWells capitols The pat FreemanlFamel DonVarner (SouthCamp) *Darrell Banks *Dee DeeSharp (SouthCamp) * AlJohnson * Percy Wiggins *-Clarence Carter(Fame) ATCONew York, N.Y. 10023 THE BLUES: A Document in Depth THIS,the first annual issue of The World of Soul, is the initial step by Billboard to document in depth the blues and its many derivatives. Blues, as a musical form, has had and continues to have a profound effect on the entire music industry, both in the United States and abroad. Blues constitute a rich cultural entity in its pure form; but its influence goes far beyond this-for itis the bedrock of jazz, the basis of much of folk and country music and it is closely akin to gospel. But finally and most importantly, blues and its derivatives- and the concept of soul-are major factors in today's pop music. In fact, it is no exaggeration to state flatly that blues, a truly American idiom, is the most pervasive element in American music COVER PHOTO today. Ray Charles symbolizes the World Therefore we have embarked on this study of blues. -

Thanks to John Frank of Oakland, California for Transcribing and Compiling These 1960S WAKY Surveys!

Thanks to John Frank of Oakland, California for transcribing and compiling these 1960s WAKY Surveys! WAKY TOP FORTY JANUARY 30, 1960 1. Teen Angel – Mark Dinning 2. Way Down Yonder In New Orleans – Freddy Cannon 3. Tracy’s Theme – Spencer Ross 4. Running Bear – Johnny Preston 5. Handy Man – Jimmy Jones 6. You’ve Got What It Takes – Marv Johnson 7. Lonely Blue Boy – Steve Lawrence 8. Theme From A Summer Place – Percy Faith 9. What Did I Do Wrong – Fireflies 10. Go Jimmy Go – Jimmy Clanton 11. Rockin’ Little Angel – Ray Smith 12. El Paso – Marty Robbins 13. Down By The Station – Four Preps 14. First Name Initial – Annette 15. Pretty Blue Eyes – Steve Lawrence 16. If I Had A Girl – Rod Lauren 17. Let It Be Me – Everly Brothers 18. Why – Frankie Avalon 19. Since You Broke My Heart – Everly Brothers 20. Where Or When – Dion & The Belmonts 21. Run Red Run – Coasters 22. Let Them Talk – Little Willie John 23. The Big Hurt – Miss Toni Fisher 24. Beyond The Sea – Bobby Darin 25. Baby You’ve Got What It Takes – Dinah Washington & Brook Benton 26. Forever – Little Dippers 27. Among My Souvenirs – Connie Francis 28. Shake A Hand – Lavern Baker 29. It’s Time To Cry – Paul Anka 30. Woo Hoo – Rock-A-Teens 31. Sand Storm – Johnny & The Hurricanes 32. Just Come Home – Hugo & Luigi 33. Red Wing – Clint Miller 34. Time And The River – Nat King Cole 35. Boogie Woogie Rock – [?] 36. Shimmy Shimmy Ko-Ko Bop – Little Anthony & The Imperials 37. How Will It End – Barry Darvell 38. -

Sweet Soul Music 1961-1965

SWEET SOUL MUSIC 1961-1965 • A sequel to Bear Family's highly acclaimed, award-winning R&B series 'Blowin' The Fuse.' • All the greatest and most influential hits as R&B became Soul in the 1960s! • All original versions! The ultimate soul collection on ten individual CDs… the first five are ready now! • The soundtrack to the 1960s! • Massive booklets with detailed notes, incredible photos, and ephemera. It was a turbulent era. Over the course of ten years, R&B became soul music, and soul music became the soundtrack to a social revolution known throughout the world as Civil Rights. The story of those ten incredible years is told in full for the first time on Bear Family's 'Sweet Soul Music' series. Some record companies have compiled anthologies from their own vaults but Bear Family has gone to every record company… great and small… in search of the greatest music and the finest sound quality. The first five volumes cover the years 1961-1965. The first rumblings of civil rights and soul music were being heard. Black music was rediscovering its gospel roots and inalienable soul. It's an incredible story that plays out before your eyes and ears as you listen to the music and read the in-depth commentary by Colin Escott and Bill Dahl. The prelude to this series, 'Blowin' The Fuse,' covered R&B from 1945-1960. It garnered awards and general acclaim. It was hailed as definitive. Now here comes the sequel. Compiled with love by Dave 'Daddy Cool' Booth. Hits? Too many to mention.