The Importance of Shortleaf Pine for Wildlife and Diversity in Mixed Oak-Pine Forests and in Pine-Grassland Woodlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

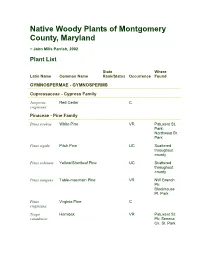

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland ~ John Mills Parrish, 2002 Plant List State Where Latin Name Common Name Rank/Status Occurrence Found GYMNOSPERMAE - GYMNOSPERMS Cupressaceae - Cypress Family Juniperus Red Cedar C virginiana Pinaceae - Pine Family Pinus strobus White Pine VR Patuxent St. Park; Northwest Br. Park Pinus rigida Pitch Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus echinata Yellow/Shortleaf Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus pungens Table-mountain Pine VR NW Branch Pk; Blockhouse Pt. Park Pinus Virginia Pine C virginiana Tsuga Hemlock VR Patuxent St. canadensis Pk; Seneca Ck. St. Park ANGIOSPERMAE - MONOCOTS Smilacaceae - Catbrier Family Smilax glauca Glaucous Greenbrier C Smilax hispida Bristly Greenbrier UC/R Potomac (syn. S. River & Rock tamnoides) Ck. floodplain Smilax Common Greenbrier C rotundifolia ANGIOSPERMAE - DICOTS Salicaceae - Willow Family Salix nigra Black Willow C Salix Carolina Willow S3 R Potomac caroliniana River floodplain Salix interior Sandbar Willow S1/E VR/X? Plummer's & (syn. S. exigua) High Is. (1902) (S.I.) Salix humilis Prairie Willow R Travilah Serpentine Barrens Salix sericea Silky Willow UC Little Bennett Pk.; NW Br. Pk. (Layhill) Populus Big-tooth Aspen UC Scattered grandidentata across county - (uplands) Populus Cottonwood FC deltoides Myricaceae - Bayberry Family Myrica cerifera Southern Bayberry VR Little Paint Branch n. of Fairland Park Comptonia Sweet Fern VR/X? Lewisdale, peregrina (pers. com. C. Bergmann) Juglandaceae - Walnut Family Juglans cinerea Butternut S2S3 R -

Pinus Echinata Shortleaf Pine

PinusPinus echinataechinata shortleafshortleaf pinepine by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia One of the most widespread pines of the Eastern United Sates is Pinus echinata, shortleaf pine. Shortleaf pine was identified and named in 1768. The scientific name means a “prickly pine cone tree.” Other common names for shortleaf pine include shortstraw pine, yellow pine, Southern yellow pine, shortleaf yellow pine, Arkansas soft pine, Arkansas pine, and old field pine. Among all the Southern yellow pines it has the greatest range and is most tolerant of a variety of sites. Shortleaf pine grows Southeast of a line between New York and Texas. It is widespread in Georgia except for coastal coun- ties. Note the Georgia range map figure. Pinus echinata is found growing in many mixtures with other pines and hardwoods. It tends to grow on medium to dry, well-drained, infertile sites, as compared with loblolly pine (Pinus taeda). It grows quickly in deep, well-drained areas of floodplains, but cannot tolerate high pH and high calcium concentrations. Compared with other Southern yellow pines, shortleaf is less demanding of soil oxygen content and essential element availability. It grows in Hardiness Zone 6a - 8b and Heat Zone 6-9. The lowest number of Hardiness Zone tends to delineate the Northern range limit and the largest Heat Zone number tends to define the South- ern edge of the range. This native Georgia pine grows in Coder Tree Grow Zone (CTGZ) A-D (a mul- tiple climatic attribute based map), and in the temperature and precipitation cluster based Coder Tree Planting Zone 1-6. -

Introgression Between Pinus Taeda L. and Pinus Echinata Mill

Introgression between Pinus taeda L. and Pinus echinata Mill. Jiwang Chen 1, C. G. Tauer l , Guihua Bai1, and Yinghua Huang1 Key words: cpDNA; introgression; microsatellite; nuclear ribosomal DNA; loblolly pine; shortleaf pine INTRODUCTION Loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.) and shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata Mill.) have widely overlapping geographic ranges. Hybridization between the two species has interested tree breeders for a long time. Morphologically, the two pine species are different. The needles of loblolly pine are 6 to 9 inches long, usually with three yellow-green needles per fascicle; but shortleaf pine needles are 3 to 5 inches long, with two or three dark yellow- green slender and flexible needles per fascicle. Loblolly pine also has larger cones than shortleaf, as well as other differences, however, these characters offer limited help when the genotypes of the parents and their probable hybrids are compounded by environmental factors The limitations of morphological characters resulted in the identification of the allozyme marker IDH (isocitrate dehydrogenase) to identify hybrids (Huneycutt and Askew, 1989). The high frequency of IDH variation seen in natural shortleaf pine populations outside the natural range of loblolly pine (Rajiv et al., 1997) suggests either profuse hybridization between the two species or that IDH is an unreliable marker. These data required us to look for new markers to confirm the identity of putative hybrids. A more extensive study (relative to the study of Rajiv et al., 1997), sampling a larger portion of shortleaf-loblolly pine sympatric population, was conducted to further explore the nature and extent of these hybrids in the native populations. -

![SHORTLEAF PINE [Pinaceae] Pinus Echinata Miller](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6490/shortleaf-pine-pinaceae-pinus-echinata-miller-586490.webp)

SHORTLEAF PINE [Pinaceae] Pinus Echinata Miller

Vascular Plants of Williamson County Pinus echinata − SHORTLEAF PINE [Pinaceae] Pinus echinata Miller (possible selection, mixed-sized plants in woodland of escaped plants originating from cultivated specimens), SHORTLEAF PINE. Tree, evergreen, with 1 trunk to 30 cm diameter (non-cultivated), in range 4−10 m tall (reproductive); monoecious; shoots with long shoot-short shoot organization, long shoot growth beginning in late March, with closely spaced, nonphotosynthetic scale leaves along new axis (new spring growth after pollination begins), springtime long shoot initially to 200 × 8 mm before foliage leaf elongating, at each node having a scalelike primary leaf but immediately producing a short shoot in the axil of scale leaf (sylleptic development) = a “fascicle” of 2−3 photosynthetic leaves (needles) held together by several tightly wrapped papery (scarious) leaves at the base, glabrous, having resin ducts within plant, aromatic, especially when crushed or damaged. Stems: internodes relatively short hidden by persistent bases of scale leaves; young twigs flexible, lacking leaves when > 4 mm diameter, with helically arranged remnants of scale leaves; older stems with woody seed cones mostly 7−8 mm diameter shedding tannish gray leaf bases and forming light brown periderm; bark large- scaly, not peeling and tightly attached, gray, not obviously resinous. Leaves: of 3 types (scale, foliage, wrapper); scale leaves on new long shoots helically alternate, simple, sessile with decurrent bases; foliage leaves (needles) terminal and mostly -

Pinus Echinata)-Hardwood Mixtures in Low Quality Mixed Upland Hardwood Stands Using Cluster Planting and Natural Regeneration

Article Restoration of Shortleaf Pine (Pinus echinata)-Hardwood Mixtures in Low Quality Mixed Upland Hardwood Stands Using Cluster Planting and Natural Regeneration David Clabo 1,* and Wayne Clatterbuck 2 1 Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia, 4601 Research Way, Tifton, GA 31793, USA 2 Department of Forestry, Wildlife & Fisheries, University of Tennessee, 274 Ellington Plant Sciences Building, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-229-386-3672 Received: 3 April 2020; Accepted: 15 April 2020; Published: 17 April 2020 Abstract: Cluster planting of shortleaf pine, along with various site preparation and release treatments, were tested to restore mixed shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata Mill.)–hardwood stands in areas where the shortleaf pine has diminished in recent years. Shortleaf pine–hardwood mixtures were once a common forest type throughout the Cumberland Mountains and Plateau physiographic regions of the southeastern United States. Knowledge of how to restore shortleaf pine–hardwood mixtures is limited throughout shortleaf pine’s large native range. The objectives of this study were to compare planted shortleaf pine and natural hardwood regeneration survival, growth, and composition following various site preparation and early release treatments. Cluster planting and partial timber harvesting were used to reintroduce shortleaf pine and create two-aged stands in the Cumberland Mountains of Tennessee, USA. Results indicated that shortleaf pine survival, basal diameter, and height growth did not differ following four growing seasons among treatments. Natural regeneration stem densities and heights within shortleaf pine clusters did not differ significantly by treatment. Natural regeneration stem densities differed by species group and height class across the site, while the treatment species interaction term was also significant. -

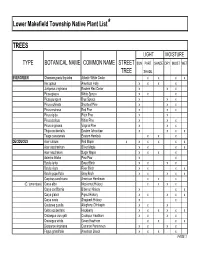

Native Plant List Trees.XLS

Lower Makefield Township Native Plant List* TREES LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE EVERGREEN Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar x x x x IIex opaca American Holly x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar x x x Picea glauca White Spruce x x x Picea pungens Blue Spruce x x x Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine x x x Pinus resinosa Red Pine x x x Pinus rigida Pitch Pine x x Pinus strobus White Pine x x x Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine x x x Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae x x x x Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock xx x DECIDUOUS Acer rubrum Red Maple x x x x x x Acer saccharinum Silver Maple x x x x Acer saccharum Sugar Maple x x x x Asimina triloba Paw-Paw x x Betula lenta Sweet Birch x x x x Betula nigra River Birch x x x x Betula populifolia Gray Birch x x x x x Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam x x x (C. tomentosa) Carya alba Mockernut Hickory x x x x Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory x x x Carya glabra Pignut Hickory x x x x x Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory x x Castanea pumila Allegheny Chinkapin xx x Celtis occidentalis Hackberry x x x x x x Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur Hawthorn x x x x Crataegus viridis Green Hawthorn x x x x Diospyros virginiana Common Persimmon x x x x Fagus grandifolia American Beech x x x x PAGE 1 Exhibit 1 TREES (cont'd) LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE DECIDUOUS (cont'd) Fraxinus americana White Ash x x x x Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash x x x x x Gleditsia triacanthos v. -

Pinus Echinata, Shortleaf Pine

PinusPinus echinataechinata shortleafshortleaf pinepine by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia One of the most widespread pines of the Eastern United Sates is Pinus echinata, shortleaf pine. Shortleaf pine was identified and named in 1768. The scientific name means a “prickly pine cone tree.” Other common names for shortleaf pine include shortstraw pine, yellow pine, Southern yellow pine, shortleaf yellow pine, Arkansas soft pine, Arkansas pine, and old field pine. Among all the Southern yellow pines it has the greatest range and is most tolerant of a variety of sites. Shortleaf pine grows Southeast of a line between New York and Texas. It is widespread in Georgia except for coastal coun- ties. Note the Georgia range map figure. Pinus echinata is found growing in many mixtures with other pines and hardwoods. It tends to grow on medium to dry, well-drained, infertile sites, as compared with loblolly pine (Pinus taeda). It grows quickly in deep, well-drained areas of floodplains, but cannot tolerate high pH and high calcium concentrations. Compared with other Southern yellow pines, shortleaf is less demanding of soil oxygen content and essential element availability. It grows in Hardiness Zone 6a - 8b and Heat Zone 6-9. The lowest number of Hardiness Zone tends to delineate the Northern range limit and the largest Heat Zone number tends to define the South- ern edge of the range. This native Georgia pine grows in Coder Tree Grow Zone (CTGZ) A-D (a mul- tiple climatic attribute based map), and in the temperature and precipitation cluster based Coder Tree Planting Zone 1-6. -

Pinus Echinata Mill.) AND

DYNAMICS OF UNDERTORY SHORTLEAF PINE (Pinus echinata Mill.) AND HARDWOOD AFTER THINNING SHORTLEAF PINE FORESTS IN THE SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES By ANUP KC Bachelor of Science in Forestry Institute of Forestry, TU Pokhara, Nepal 2007 Master of Science in Aquaculture and Fisheries University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff Pine Bluff, Arkansas 2011 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July, 2016 DYNAMICS OF UNDERTORY SHORTLEAF PINE (Pinus echinata Mill.) AND HARDWOOD AFTER THINNING SHORTLEAF PINE FORESTS IN THE SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES Dissertation Approved: Thomas B. Lynch Dissertation Advisor Lan Zhu Rod Will Stephen Hallgren ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere thanks to my major advisor, Dr. Thomas B. Lynch, for his guidance and support during the last four years of my research. I am thankful to Dr. Rodney Will, Dr. Lan Zhu, and Dr. Stephen Hallgren for serving on my dissertation committee. I am also thankful to the Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management for funding my research and education for four years. I am especially thankful to my family. I would like to thank my father and mother for everything that they have done for me in this life. Thank you to my lovely wife, Ambika Shrestha, for her hard work, patience, and the encouragement throughout this journey. I thank my daughter Ansu for being the most adorable little girl I have ever encountered. I also want to express my sincere thanks to my uncles and aunts for their unwavering love and support. -

Strategic Assessment for Shortleaf Pine

Strategic Assessment for Shortleaf Pine Rodney Will, John Stewart, Tom Lynch, Don Turton, Adam Maggard, Curtis Lilly Oklahoma State University Division of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources Natural Resource Ecology and Management Kurt Atkinson Oklahoma Forestry Services Department of Agriculture, Food and Forestry May 2013 Acknowledgements This Strategic Assessment for Shortleaf Pine is one deliverable of a FY 2010 competitive grant project funded by the USDA Forest Service - Southern Region using federal Forest Stewardship Program dollars. Financial support from the U.S. Forest Service and the Forest Stewardship Program is gratefully acknowledged. "The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer." Purpose This grant project was cooperatively undertaken by the State Foresters of Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas and North Carolina in support of a landscape-level Shortleaf Pine Initiative underway across the South. -

Using Fire to Restore Shortleaf Pine (Pinus Echinata) Ecosystems

Using fire to restore shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata) ecosystems severely impacted by southern pine beetle (Dendroctonus frontalis) Oral presentation to Berry College, Rome, GA April 2007 Katherine J. Elliott and James M. Vose, Jennifer D. Knoepp, and Barton D. Clinton Coweeta Hydrologic Laboratory, Southern Research Station, Forest Service, US Department of Agriculture Presentation Outline ¾Background ¾Fire History ¾Coweeta’s fire studies ¾Restoration of shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata) Was fire important in the history of the southern Appalachians? • Native American history • Early explorers • Paleoecology • Fire scars • Plant & ecosystem traits Native American History “… in those days they said the mountains were like a park. Yeah. You could walk up in the mountains and there were huge trees everywhere and there was grass even in between the trees and not that much brush. And so it was like a walking park, you know, and now if you go up there there’s just a lot of brush, a lot of different kinds of things.” Cherokee elder (Cooley 2004, MS Thesis) “Now, now that’s the way the old people [built] a fire and they set fire all, all over .. in April. And sometimes in May when there ain’t too much wind..” Cherokee elder (Cooley 2004) Early explorer’s accounts ¾William Bartram’s journey through the Little Tennessee River valley of Georgia and North Carolina in the 1770s ¾Andrew Ellicott’s similar route in 1812 ¾Robert Love’s survey of Macon and Swain counties, North Carolina in 1820 40 30 Pine 20 % Pollen 10 0 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 5 2 4 Ragweed 3 Charcoal 2 Charcoal % Pollen 1 0 0 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 Year AD redrawn from Clark et al. -

Pinus Echinata

Shortleaf Pine Pinus echinata As a Reclamation Species on Former Mine Sites 2015 National Meeting of the American Society of Mining and Reclamation & the Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative Lexington, Kentucky June 10, 2015 Holly Campbell Extension Associate of Forest Resources Southern Regional Extension Forestry (SREF) Mining in Appalachia • 600,000 ha (1.5 million ac) • SMCRA-1977 • Erosion prevention • Wildlife habitat or grazing • After bond release Strip mine in West Virginia Credit: National Geographic (2007) • Lands mostly unmanaged • Resulting vegetation • Moderate ecological value • Minimal/ no economic value • ARRI created (2004) • Promotes Forestry Reclamation Approach (FRA) Forestry Reclamation Approach on former mining site with Dr. James Burger Powell River Project, VA Tech Pines & Reclaimed Mine Sites • Pine as a pioneer species-assist later successional species • Decrease bulk density (Asby, 1989) • Increase soil nutrients • Organic matter • Ectomycorrhizae (Callaway, 1995) • Provide shade (Bauman, et al., 2012) • Pine as long term component of hardwood stands • Wildlife benefits Shortleaf pine and black locust on • Economic benefits reclaimed mine site-Tennessee Pre-SMCRA Research- mixed results for shortleaf pine Tree Height (ft) & Survival (%) after 6 yrs 10 53% Kring, 1967 • Eastern Tennessee site-spoil bank (Kring, 1967)-5 pines 8 • Soils: low pH (4.1-5.3), P, and K 74% ) 53% ft • S. Illinois reclamation site (Ashby 6 72% & Baker, 1968) Height ( Height • Soils: High pH (6.0-8.1), low N 4 49% survival • Wilson Mtn strip mine reclamation, TN (1975) 2 • Slope influences species dominance • North Aspect-Yellow poplar • South Aspect-Shortleaf pine Post-SMCRA Research- shortleaf pine still struggles Effect of Competition Control on Survival & Height 225 Torbert, et al. -

Historic Shortleaf Pine (Pinus Echinata Mill.) Abundance and Fire

~M@W~W-------------------------------------------------------- Historic Shortleaf Pine (Pinus echinata Mill.) Abundance and Fire Frequency in a Mixed Oak - Pine Forest (MOFEP, Site 8) Richard P. Guyette and Daniel C. Dey1 Abstract.-Historic and present day shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata Mill.) abundance was measured and compared using 84 plots along 16 transects in site 8 of the Missouri Ozark Forest Ecosystem Project. Remnant pine stumps were used to estimate historic pine density and to construct a dendrochronological record of fire frequency. There has been a 66-percent reduction in the relative abundance of pine from historic levels (circa 1900) within the study area. Present day pine abundance is only 21 percent of historic levels on slopes and only 25 percent of historic levels on ridges. Historic and present day pine abundance was not significantly different on toe slopes and in riparian areas. Elevation, slope, and aspect were significantly (P < 0.05) correlated with changes in pine abundance. Pine abundance was reduced at 60 percent of the plot locations, increased at 20 percent of the plots, and remained the same at 9 percent of the plots. Mean fire-free intetvals were 6.3 years for the period 1701 to 1820 and 3.1 years for the period 1821 to 1900. Pattems in the change in pine abundance were consistent with changes in fire frequency and expected fire behavior at a landscape level. In some areas, such as riparian or road corridors, it was difficult to estimate historic pine abundance because of the disturbance of pine stumps and remnants. Knowledge of historic shortleaf pine abundance trees in Missouri.