The Scottish Recoinage of 1707-9 and Its Aftermath Atholl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War of Words: Daniel Defoe and the 1707 Union Anne M

War of Words: Daniel Defoe and the 1707 Union Anne M. McKim Thus, on both Sides, the case stood between the nations, a Pen and Ink War made a daily Noise in either Kingdom, and this served to Exasperate the People in such a manner, one against another, that never have two Nations Run upon one another in such a manner, and come off without Blows.1 The Union of Scotland and England on 1 May 1707 was – and for some still is – undoubtedly contentious. Polemic and political pamphleteering flourished at the time, reflecting and fanning the debate, while the newssheets and jour- nals of the day provided lively opinion pieces and a good deal of propaganda. Recent commentators have recognised the importance of public discourse and public opinion regarding the Union on the way to the treaty. Leith Davis goes as far as to say that the ‘new British nation was constructed from the dialogue that took place regarding its potential existence’.2 While the treaty articles were still being debated by the last Scottish parlia- ment, Daniel Defoe, who had gone to Scotland specifically to promote the Union, began compiling his monumental History of the Union of Great Britain in Edinburgh.3 He expected to see it published before the end of 1707 although, for reasons that are still not entirely clear, it was not published until late 1709 or early 1710.4 As David Hayton notes, ‘a great deal of it must already have 1 Daniel Defoe, The History of the Union of Great Britain, D. W. -

Royal Mint Trading Fund Annual Report | 2011-12

Royal Mint Trading Fund Annual Report | 2011-12 Making Money for Everyone Royal Mint Trading Fund Annual Report and Accounts 2011-12 Presented to the Parliament pursuant to section 4(6) of the Government Trading Funds Act 1973 as amended by the Government Trading Act 1990 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 5 July 2012 HC 264 | London: The Stationery Office | £ 21.25 © Crown copyright 2012 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or email: [email protected]. This publication is available for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk. This document is also available from our website at www.royalmint.com. ISBN: 9780102976519 Printed in the UK for The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID 2486320 06/12 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Annual Report and Accounts 2011-12 The Royal Mint Trading Fund Royal Mint Trading Fund Accounting Officer is Jeremy Pocklington The Royal Mint Limited Directors The Royal Mint Museum -

Guide to the Collection of Irish Antiquities

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF SCIENCE AND ART, DUBLIN. GUIDE TO THE COLLECTION OF IRISH ANTIQUITIES. (ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY COLLECTION). ANGLO IRISH COINS. BY G COFFEY, B.A.X., M.R.I.A. " dtm; i, in : printed for his majesty's stationery office By CAHILL & CO., LTD., 40 Lower Ormond Quay. 1911 Price One Shilling. cj 35X5*. I CATALOGUE OF \ IRISH COINS In the Collection of the Royal Irish Academy. (National Museum, Dublin.) PART II. ANGLO-IRISH. JOHN DE CURCY.—Farthings struck by John De Curcy (Earl of Ulster, 1181) at Downpatrick and Carrickfergus. (See Dr. A. Smith's paper in the Numismatic Chronicle, N.S., Vol. III., p. 149). £ OBVERSE. REVERSE. 17. Staff between JiCRAGF, with mark of R and I. abbreviation. In inner circle a double cross pommee, with pellet in centre. Smith No. 10. 18. (Duplicate). Do. 19. Smith No. 11. 20. Smith No. 12. 21. (Duplicate). Type with name Goan D'Qurci on reverse. Obverse—PATRIC or PATRICII, a small cross before and at end of word. In inner circle a cross without staff. Reverse—GOAN D QVRCI. In inner circle a short double cross. (Legend collected from several coins). 1. ^PIT .... GOANDQU . (Irish or Saxon T.) Smith No. 13. 2. ^PATRIC . „ J<. ANDQURCI. Smith No. 14. 3. ^PATRIGV^ QURCI. Smith No. 15. 4. ^PA . IOJ< ^GOA . URCI. Smith No. 16. 5. Duplicate (?) of S. No. 6. ,, (broken). 7. Similar in type of ob- Legend unintelligible. In single verse. Legend unin- inner circle a cross ; telligible. resembles the type of the mascle farthings of John. Weight 2.7 grains ; probably a forgery of the time. -

The Ionian Islands in British Official Discourses; 1815-1864

1 Constructing Ionian Identities: The Ionian Islands in British Official Discourses; 1815-1864 Maria Paschalidi Department of History University College London A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to University College London 2009 2 I, Maria Paschalidi, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Utilising material such as colonial correspondence, private papers, parliamentary debates and the press, this thesis examines how the Ionian Islands were defined by British politicians and how this influenced various forms of rule in the Islands between 1815 and 1864. It explores the articulation of particular forms of colonial subjectivities for the Ionian people by colonial governors and officials. This is set in the context of political reforms that occurred in Britain and the Empire during the first half of the nineteenth-century, especially in the white settler colonies, such as Canada and Australia. It reveals how British understandings of Ionian peoples led to complex negotiations of otherness, informing the development of varieties of colonial rule. Britain suggested a variety of forms of government for the Ionians ranging from authoritarian (during the governorships of T. Maitland, H. Douglas, H. Ward, J. Young, H. Storks) to representative (under Lord Nugent, and Lord Seaton), to responsible government (under W. Gladstone’s tenure in office). All these attempted solutions (over fifty years) failed to make the Ionian Islands governable for Britain. The Ionian Protectorate was a failed colonial experiment in Europe, highlighting the difficulties of governing white, Christian Europeans within a colonial framework. -

Union with Scotland Act 1706

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Union with Scotland Act 1706. (See end of Document for details) Union with Scotland Act 1706 1706 CHAPTER 11 6 Ann X1 An Act for an Union of the Two Kingdoms of England and Scotland Most gracious Sovereign Recital of Articles of Union, dated 22d July, 5 Ann.; and of an Act of Parliament passed in Scotland, 16th January, 5 Ann. Whereas Articles of Union were agreed on the Twenty Second day of July in the Fifth year of Your Majesties reign by the Commissioners nominated on behalf of the Kingdom of England under Your Majesties Great Seal of England bearing date at Westminster the Tenth day of April then last past in pursuance of an Act of Parliament made in England in the Third year of Your Majesties reign and the Commissioners nominated on the behalf of the Kingdom of Scotland under Your Majesties Great Seal of Scotland bearing date the Twenty Seventh day of February in the Fourth year of Your Majesties Reign in pursuance of the Fourth Act of the Third Session of the present Parliament of Scotland to treat of and concerning an Union of the said Kingdoms And Whereas an Act hath passed in the Parliament of Scotland at Edinburgh the Sixteenth day of January in the Fifth year of Your Majesties reign wherein ’tis mentioned that the Estates of Parliament considering the said Articles of Union of the two Kingdoms had agreed to and approved of the said Articles of Union with some Additions and Explanations And that Your Majesty with Advice and Consent of the Estates -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

Reclaiming Their Shadow: Ethnopolitical Mobilization in Consolidated Democracies

Reclaiming their Shadow: Ethnopolitical Mobilization in Consolidated Democracies Ph. D. Dissertation by Britt Cartrite Department of Political Science University of Colorado at Boulder May 1, 2003 Dissertation Committee: Professor William Safran, Chair; Professor James Scarritt; Professor Sven Steinmo; Associate Professor David Leblang; Professor Luis Moreno. Abstract: In recent decades Western Europe has seen a dramatic increase in the political activity of ethnic groups demanding special institutional provisions to preserve their distinct identity. This mobilization represents the relative failure of centuries of assimilationist policies among some of the oldest nation-states and an unexpected outcome for scholars of modernization and nation-building. In its wake, the phenomenon generated a significant scholarship attempting to account for this activity, much of which focused on differences in economic growth as the root cause of ethnic activism. However, some scholars find these models to be based on too short a timeframe for a rich understanding of the phenomenon or too narrowly focused on material interests at the expense of considering institutions, culture, and psychology. In response to this broader debate, this study explores fifteen ethnic groups in three countries (France, Spain, and the United Kingdom) over the last two centuries as well as factoring in changes in Western European thought and institutions more broadly, all in an attempt to build a richer understanding of ethnic mobilization. Furthermore, by including all “national -

Good Grade. 6. 1916 Shilling

1. 1696 crown. 45. Qty. pennies etc. 3.3 kg. 2. 2 x 1937 crown. 46. Boxed set of 4 crowns. 3. 1836 ½ crown. 47. 1914 half crown – better grade. 4. 2 x 1935 crowns. 48. 1889 crown. 5. 1918 Rupee – good grade. 49. 1889 crown. 6. 1916 shilling – good grade. 50. USA 1922 Dollar. 7. 1927 wreath crown. 51. Enamel George 111 crown. 8. USA silver dollar 1922. 52. 1922 Australia florins. 9. Silver Death of Victoria medallion. 53. 1939 penny – good grade and ½ 10. 1806 penny – good grade. penny. 11. 2 x 1951 crown and 1953 crown. 54. Proof silver £1 coins. 12. 3 x 1951 crowns. 55. 1998 proof set piedfort £1 coin. 13. 1895 crown. 56. 1993 proof set piedfort £1 coin. 14. 1943 ½ Dollar. 57. 2001 proof set piedfort £1 coin. 15. 3 piece enamel type coin jewellery. 58. 1992 proof silver piedfort 50p. 16. Box medallion. 59. Good grade 1891 USA dime. 17. Cigarette cards. 60. Good grade 1836 Groat. 18. Bank notes etc. 61. Boxed set of 3 D.Day crowns. 19. Tin of coins. 62. 2 proof silver 10p. 1992. 20. Purse of coins. 63. Proof 2001 £5 coin. 21. 1857 USA 1 cent. 64. 1988 proof set UK. 22. Cheltenham penny token 1812. 65. 1989 proof set UK. 23. 3 tokens. 66. 1953 proof set. 24. 18th century Irish ½ pennies. 67. 1935 and 1937 crown. 25. 1813 IOM penny. 68. 2 x 1935 crown. 26. 3 Victorian ½ farthings. 69. 1889 crown. 27. Victoria farthings 1839 onwards. 70. 1889 crown. 28. Canada 25d. -

Scotland the Brave? an Overview of the Impact of Scottish Independence on Business

SCOTLAND THE BRAVE? AN OVERVIEW OF THE IMPACT OF SCOTTISH INDEPENDENCE ON BUSINESS JULY 2021 SCOTLAND THE BRAVE? AN OVERVIEW OF THE IMPACT OF SCOTTISH INDEPENDENCE ON BUSINESS Scottish independence remains very much a live issue, as First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, continues to push for a second referendum, but the prospect of possible independence raises a host of legal issues. In this overview, we examine how Scotland might achieve independence; the effect of independence on Scotland's international status, laws, people and companies; what currency Scotland might use; the implications for tax, pensions and financial services; and the consequences if Scotland were to join the EU. The Treaty of Union between England of pro-independence MSPs to 72; more, (which included Wales) and Scotland even, than in 2011. provided that the two Kingdoms "shall upon the first day of May [1707] and Independence, should it happen, will forever after be United into one Kingdom affect anyone who does business in or by the Name of Great Britain." Forever is with Scotland. Scotland can be part of a long time. Similar provisions in the Irish the United Kingdom or it can be an treaty of 1800 have only survived for six independent country, but moving from out of the 32 Irish counties, and Scotland the former status to the latter is highly has already had one referendum on complex both for the Governments whether to dissolve the union. In that concerned and for everyone else. The vote, in 2014, the electorate of Scotland rest of the United Kingdom (rUK) could decided by 55% to 45% to remain within not ignore Scotland's democratic will, but the union, but Brexit and the electoral nor could Scotland dictate the terms on success of the SNP mean that Scottish which it seceded from the union. -

Exchange of Irish Coins

IR£ COINS ONLY Irish Pound coins can be submitted for value exchange via the drop box located at the Central Bank of Ireland in North Wall Quay or by post to: Central Bank of Ireland, PO Box 61, P3, Sandyford, Dublin 16. Please note submissions cannot be dropped in to the Sandyford address. Please sort your submission in advance as follows: Submissions must include: 1. Completed form 2. Bank account details for payment 3. A copy of photographic ID for submissions over €100 More information: See the “Consumer Hub” area on www.centralbank.ie, email [email protected], or call the Central Bank on +353 1 2245969. SUBMISSION DETAILS Please give details of the COIN(S) enclosed Quantity OFFICE USE Quantity OFFICE USE Denomination Denomination Declared ONLY Declared ONLY ¼d (Farthing) ½p (Halfpenny) ½d (Halfpenny) 1p (Penny) 1d (Penny) 2p (Two pence) 3d (Threepence) 5p (Five pence) 6d (Sixpence) 10p (Ten pence) 1s (Shilling) 20p (Twenty pence) 2s (Florin) 50p (Fifty pence) 2/6 (Half crown) £1 (One pound) 10 s (Ten Shilling) TOTAL QUANTITY Modified 16.12.19 IR£ COINS ONLY Failure to complete the form correctly will result in delay in reimbursement. Please use BLOCK CAPITALS throughout this form. Important information for submissions by companies: Please provide your CRO number: , For submissions over €100, please submit a redacted bank statement in the company name for the nominated bank account instead of photo ID. Applicant Details Applicant’s Full Name Tel Number Address Email Address For submissions over €100: Have you attached the required ID? yes To protect your personal information, please fold completed form along dotted line ensuring this side faces inward. -

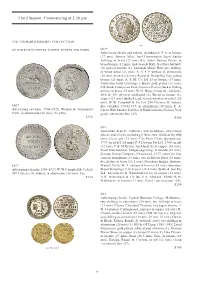

Third Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm

Third Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm THE HOWARD BROWN COLLECTION part OF AUSTRALIAN CHECKS, TOKENS, TICKETS AND PASSES 602* Advertising checks and tokens, including A. F. A. in bronze (27 mm), Barney Allen, Turf Commission Agent Lucky farthing, in brass (23 mm) (4)), Allens Battery Patent, in brass/bronze (32 mm), Anderson & Hall, Jewellers Adelaide (26 mm) in bronze (2), Annabels Music Hall, one shilling, in white metal (23 mm), A. S. F. P. uniface in aluminium (18 mm), bronze (26 mm), Assam & Darjeeling Teas, gilded bronze (26 mm), A. S. M. Co Ltd 13 in bronze (17 mm), Australian Gold Exchange 3 Bucks gold plated (32 mm), E.R.Banks Enterprises Perth, bronze (26 mm), Becker shilling uniface in brass (25 mm), W. H. Bruce, Groat St., Adelaide, 28/6 & 30/- silvered cardboard (2), Bovril in bronze (2), copper (21 mm), Bullock Lade Scotch whiskey in nickel (26 mm), W. W. Campbell & Co Ltd, 240 Clarence St, Sydney, 600* disc calendar 1904-1927, in aluminium (38 mm), E. A. Advertising calendar, 1904-1925, Watson & Gutmann's Carter Watchmaker Jeweller, St Kilda in brass (25 mm). Very Perth, in aluminium (38 mm). Very fi ne. good - extremely fi ne. (23) $150 $200 603 Australian dealers, collectors and medallists, advertising tokens and checks, including P. Bickerton, Ballarat for fi fty cents (2) in gilt (32 mm), Cut Price Coins Queensland, 1997, in nickel (26 mm), P. J. Downie Pty Ltd, 1988, in gilt (32 mm), P & M Eccles, Auckland (5) in copper (20 mm), Nicol International, badges engraving, in bronze (36 mm), Scandia Stamp Company, Chatswood, 1977, token for fi fty cents in aluminium (24 mm), two dollars in brass (24 mm), fi ve dollars in brass (28.5 mm), Sheridans Badges, Buttons, 601* Medals, Perth, W. -

Annual Report of the Director of the Mint

- S. Luriºus vsº ANNUAL REPORT Of the Director of the N/int for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1970. ANNUAL REPORT of the Director of the Mint for the fiscal year ended June 30 1970 DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY DOCUMENT NO. 3253 Director of the Mint U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1971 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $1 (paper cover) Stock Number 4805–0009 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY, BUREAU OF THE MINT, Washington, D.C., April 29, 1971. SIR: I have the honor to submit the Ninety-eighth Annual Report of the Director of the Mint, since the Mint became a Bureau within the Department of the Treasury in 1873. Annual reports of Mint activities have been made to the Secretary of the Treasury since 1835, pursuant to the act of March 3, 1835 (4 Stat. 774). Annual reports of the Mint have been made since it was established in 1792. This report is submitted in compliance with Section 345 of the Revised Statutes of the United States, 2d Edition (1878), 31 U.S.C. 253. It includes a review of the operations of the mints, assay offices, and the bullion depositories for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1970. Also contained in this edition are reports for the calendar year 1969 on U.S. gold, silver, and coinage metal production and the world's monetary stocks of gold, silver, and coins. MARY BROOKs, Director of the Mint. Hon. JoHN B. Con NALLY, Secretary of the Treasury.