The Oviposition Preference of Callosobruchus Maculatus and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microstructural Differences Among Adzuki Bean (Vigna Angularis) Cultivars

Food Structure Volume 11 Number 2 Article 9 1992 Microstructural Differences Among Adzuki Bean (Vigna Angularis) Cultivars Anup Engquist Barry G. Swanson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/foodmicrostructure Part of the Food Science Commons Recommended Citation Engquist, Anup and Swanson, Barry G. (1992) "Microstructural Differences Among Adzuki Bean (Vigna Angularis) Cultivars," Food Structure: Vol. 11 : No. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/foodmicrostructure/vol11/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Dairy Center at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Food Structure by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOOD STRUCTURE, Vol. II (1992), pp. 171-179 1046-705X/92$3.00+ .00 Scanning Microscopy International , Chicago (AMF O'Hare), IL 60666 USA MICROSTRUCTURAL DIFFERENCES AMONG ADZUKI BEAN (Vigna angularis) CULTIVARS An up Engquist and Barry G. Swanson Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-6376 Abstract Introduction Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to Adzuki beans are one of the oldest cultivated beans study mi crostructural differences among five adzuki bean in the Orient, often used for human food, prepared as a cultivars: Erimo, Express, Hatsune, Takara and VBSC. bean paste used in soups and confections (Tjahjadi and Seed coat surfaces showed different patterns of cracks , Breene, 1984). The starch content of adzuki beans is pits and deposits . Cross-sections of the seed coats re about 50 %, while the protein content ranges between vealed well organized layers of elongated palisade cell s 20%-25% (Tjahjadi and Breene, 1984) . -

![Genetic Dissection of Azuki Bean Weevil (Callosobruchus Chinensis L.) Resistance in Moth Bean (Vigna Aconitifolia [Jaqc.] Maréchal)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9543/genetic-dissection-of-azuki-bean-weevil-callosobruchus-chinensis-l-resistance-in-moth-bean-vigna-aconitifolia-jaqc-mar%C3%A9chal-59543.webp)

Genetic Dissection of Azuki Bean Weevil (Callosobruchus Chinensis L.) Resistance in Moth Bean (Vigna Aconitifolia [Jaqc.] Maréchal)

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Genetic Dissection of Azuki Bean Weevil (Callosobruchus chinensis L.) Resistance in Moth Bean (Vigna aconitifolia [Jaqc.] Maréchal) Prakit Somta 1,2,3,* , Achara Jomsangawong 4, Chutintorn Yundaeng 1, Xingxing Yuan 1, Jingbin Chen 1 , Norihiko Tomooka 5 and Xin Chen 1,* 1 Institute of Industrial Crops, Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, 50 Zhongling Street, Nanjing 210014, China; [email protected] (C.Y.); [email protected] (X.Y.); [email protected] (J.C.) 2 Department of Agronomy, Faculty of Agriculture at Kamphaeng Saen, Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen Campus, Nakhon Pathom 73140, Thailand 3 Center for Agricultural Biotechnology (AG-BIO/PEDRO-CHE), Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen Campus, Nakhon Pathom 73140, Thailand 4 Program in Plant Breeding, Faculty of Agriculture at Kamphaeng Saen, Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen Campus, Nakhon Pathom 73140, Thailand; [email protected] 5 Genetic Resources Center, Gene Bank, National Agriculture and Food Research Organization, 2-1-2 Kannondai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8602, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (P.S.); [email protected] (X.C.) Received: 3 September 2018; Accepted: 12 November 2018; Published: 15 November 2018 Abstract: The azuki bean weevil (Callosobruchus chinensis L.) is an insect pest responsible for serious postharvest seed loss in leguminous crops. In this study, we performed quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping of seed resistance to C. chinensis in moth bean (Vigna aconitifolia [Jaqc.] Maréchal). An F2 population of 188 plants developed by crossing resistant accession ‘TN67’ (wild type from India; male parent) and susceptible accession ‘IPCMO056’ (cultivated type from India; female parent) was used for mapping. -

Callosobruchus Spp.) in Vigna Crops: a Review

NU Science Journal 2007; 4(1): 01 - 17 Genetics and Breeding of Resistance to Bruchids (Callosobruchus spp.) in Vigna Crops: A Review Peerasak Srinives1*, Prakit Somta1 and Chanida Somta2 1Department of Agronomy, Faculty of Agriculture at Kamphaeng Saen, Kasetsart University, Nakhon Parham, 73140 Thailand 2Asian Regional Center, AVRDC-The World Vegetable Center, Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen Campus, Nakhon Pathom, 73140 Thailand *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Vigna crops include mungbean (V. radiata), blackgram (V. mungo), azuki bean (V. angularis) and cowpea (V. unguiculata) are agriculturally and economically important crops in tropical and subtropical Asia and/or Africa. Bruchid beetles, Callosobruchus chinensis (L.) and C. maculatus (F.) are the most serious insect pests of Vigna crops during storage. Use of resistant cultivars is the best way to manage the bruchids. Bruchid resistant cowpea and mungbean have been developed and comercially used, each with single resistance source. However, considering that enough time and evolutionary pressure may lead bruchids to overcome the resistance, new resistance sources are neccessary. Genetics and mechanism of the resistance should be clarified and understood to develop multiple resistance cultivars. Gene technology may be a choice to develop bruchid resistance in Vigna. In this paper we review sources, mechanism, genetics and breeding of resistance to C. chinensis and C. maculatus in Vigna crops with the emphasis on mungbean, blackgram, azuki bean and cowpea. Keywords: Bruchid resistance, Callosobruchus spp., Legumes, Vigna spp. INTRODUCTION The genus Vigna falls within the tribe Phaseoleae and family Fabaceae. Species in this taxon mainly distribute in pan-tropical Asia and Africa. Seven Vigna species are widely cultivated and known as food legume crops. -

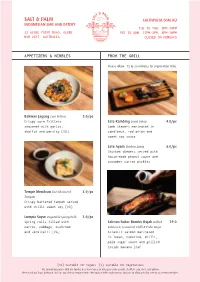

Food Is Free from Traces of Allergens Such As Nuts, Shellfish, Soy, Chilli, and Gluten

SALT & PALM SALTNPALM.COM.AU INDONESIAN BAR AND EATERY TUE TO THU: 5PM-10PM 22 GLEBE POINT ROAD, GLEBE FRI TO SUN: 12PM-3PM, 5PM-10PM NSW 2037, AUSTRALIA CLOSED ON MONDAYS APPETIZERS & NIBBLES FROM THE GRILL Please allow ±15 to 20 minutes for preparation time Bakwan Jagung Corn Fritters 3.0/pc Crispy corn fritters Sate Kambing Lamb Satay 4.5/pc seasoned with garlic, Lamb skewers marinated in shallot and parsley [VG] candlenut, red onion and sweet soy sauce Sate Ayam Chicken Satay 4.0/pc Chicken skewers served with house-made peanut sauce and cucumber carrot pickles Tempe Mendoan Fried Battered 3.0/pc Tempeh Crispy battered tempeh served with chilli sweet soy [VG] Lumpia Sayur Vegetable Spring Rolls 3.0/pc Spring rolls filled with Salmon Bakar Bumbu Rujak Grilled 29.0 carrot, cabbage, mushroom Salmon in Tamarind, Chilli & Palm Sugar and vermicelli [VG] Atlantic salmon marinated in lemon, tamarind, chilli, palm sugar sauce and grilled inside banana leaf [VG] Suitable for Vegans [V] Suitable for Vegetarians We cannot guarantee that our food is free from traces of allergens such as nuts, shellfish, soy, chilli, and gluten. Please ask our Front of House staff for any dietary requirements. We apply a 10% surcharge on Sundays to allow penalty rate for our team members. SALT & PALM SALTNPALM.COM.AU INDONESIAN BAR AND EATERY TUE TO THU: 5PM-10PM 22 GLEBE POINT ROAD, GLEBE FRI TO SUN: 12PM-3PM, 5PM-10PM NSW 2037, AUSTRALIA CLOSED ON MONDAYS FROM THE GRILL Please allow ±15 to 20 minutes for preparation time Please allow ±15 to 20 minutes for preparation time Ayam Bakar Grilled Chicken Iga Sapi Bakar Grilled Beef Grilled half chicken. -

Mung Bean Varieties

FINAL STUDY REPORT Bridger Plant Materials Center, Bridger, MT Evaluation of Cowpea and Mung Bean Varieties Mark Henning, Area Agronomist, Miles City, MT Robert Kilian, (Retired) Rangeland Management Specialist, Bridger PMC, MT ABSTRACT There is a need for well adapted warm season legumes for use in cover crop mixes in Montana and Wyoming to provide needed plant diversity in dryland cropping systems. Field observations of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) and mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) in mixes have shown limited or poor performance in terms of number of plants and vigor. To identify suitable varieties, a variety trial consisting of two mung bean and four cowpea varieties was conducted at the Bridger Plant Materials Center (BPMC) in Bridger, Montana using a randomized complete block design. There was no significant difference in biomass yields, but there were significant differences in height and days to 50% flowering. ‘Iron & Clay’ cowpea was the tallest of the six tested varieties, whereas ‘Berken’ mung bean was the shortest. ‘Iron & Clay’ and ‘Black Stallion’ cowpeas never flowered, while the other varieties flowered and produced seed. All varieties exhibited excellent vigor and health, despite poor soil structure and soil compaction, and a lack of nodulation, demonstrating the potential for these species to do well in degraded soil. There is potential for seed production in Montana of ‘Chinese Red’ cowpea, as well mung bean varieties ‘OK2000’ and ‘Berken,’ which could meet a market demand for cover crop seed and provide an alternative crop in dryland farming systems. Future research should focus on 1) seed production potential of mung bean and cowpea in Montana dryland systems, 2) evaluation of higher seed rates of cowpea and mung bean in cover crop mixes, and 3) testing whether plant habit (prostrate versus upright) has an effect on legume performance in cover crop mixes. -

Bean Beetle Nutrition and Development Lab: an Iterative Approach to Teaching Experimental Design

Tested Studies for Laboratory Teaching Proceedings of the Association for Biology Laboratory Education Vol. 37, Article 10, 2016 Bean Beetle Nutrition and Development Lab: An Iterative Approach to Teaching Experimental Design Julie Laudick1 and Christopher Beck2 1The Ohio State University, Environmental Science Graduate Program, 1680 Madison Ave., Wooster OH 44691 USA 2Emory University, Department of Biology, 1510 Clifton Road NE, Atlanta GA 30322 USA ([email protected]; [email protected]) In this lab, students work first independently and then collaboratively to formulate a novel hypothesis and design an experiment to test it. Bean beetle (Callosobruchus maculatus) larvae can develop inside multiple types of host beans, but they develop more quickly and grow larger in more nutritious beans. Students test the effects of a nutrient of interest on larval development by adding it to flour made from nutrient deficient beans. A female beetle will lay eggs on a gelatin capsule full of the modified bean flour, as she would on a natural bean. The larvae developing inside the experimental capsules are compared with control capsules. Keywords: inquiry-based learning, hypothesis formulation, experimental design, bean beetles Introduction Bean beetle labs are particularly attractive for introductory and non-majors courses because students When covering the nature of science, biology face fewer technical and conceptual hurdles than they educators often emphasize that science is a process of would in microbiology or molecular biology labs. Less inquiry, not simply a collection of facts. Students rarely time is required for students to understand the system, and experience this full process in lab courses because more time can be spent designing, refining and original research is time consuming, resource-intensive, implementing experiments. -

Identification of Lentil Genotypes Resistant to Bruchid (Callosobruchus Chinensis L.) and Selection of Diverse Parental Pair A

Journal of Crop and Weed, 14(3): 136-143 (2018) Identification of lentil genotypes resistant to bruchid (Callosobruchus chinensis L.) and selection of diverse parental pair A. K. SAHA, S. SARKAR AND S. BHATTACHARYYA Department of Genetics and Plant Breeding, Crop Research Unit Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Mohanpur-741252, Nadia, West Bengal Received : 27-08-18 ; Revised : 28-11-18 ; Accepted : 02-12-18 ABSTRACT Bruchid (Callosobruchus chinensis L.) is the most devastating storage pest of the pulses in storage condition. Lentil is one of the important pulse cropsand scanty of literature is available regarding the bruchid resistance in this crop. Climatic condition of West Bengal favours the pulse beetle infestation during storage of pulses. Therefore, we investigated the potential resistant sources among 94 lentil cultivated genotypes by feeding assay against this pest in laboratory condition. Ten high yielding genotypes were screened based on their resistance. Diversity analysis was performed by utilizing 12 phenotypic markers and 12 SSR markers to decipher the best possible parental pair. Based on this study it was found that WBL-77 and Precoz is the best parental pair. Keywords: Bruchid, diversity, lentil, resistance and SSR Lentil is the most preferred pulse in West Bengal as pod wall and feed within the seeds (Southgate, 1979). the Bengali people consume it as dal, almost daily, along Male has a longer life span than the female beetle. with their vaat i.e. rice. Although lentil productivity in Longevity of adults for males ranged from 9 to 14 days West Bengal (963 kg ha-1) is higher than that of national with average of 11.0±1.87 days and for females was average (705 kg ha-1), astonishingly it is produced very ranged 9 to 12 days with an average of 9.6±1.14 days. -

Effect of Hot and Cold Treatments for the Management of Pulse Beetle Callosobruchus Maculatus (Fab) in Pulses

IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science (IOSR-JAVS) e-ISSN: 2319-2380, p-ISSN: 2319-2372. Volume 3, Issue 3 (May. - Jun. 2013), PP 29-33 www.iosrjournals.org Effect of hot and cold treatments for the management of Pulse beetle Callosobruchus maculatus (Fab) in pulses J.Alice R.P.Sujeetha1 and N.Srikanth2 1Department of Food Microbiology,Indian Institute of Crop ProcessingTechnology,Thanjavur, 613 005,Tamil Nadu,India 2Department of Entomology,Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru College of Agriculture & Research Institute,Karaikal, Puducherry , 609 603 -India Abstract: The pulse beetle C. maculatus (Fab.) is a major pest of economically important leguminous grains, such as cow peas, lentils, green gram, and black gram. Effect of sun drying on oviposition of pulse beetle, C. maculatus showed 100 per cent egg mortality during the second, third and fourth months. It was observed that there is no significant difference among the exposure periods .Effect of sun drying on adult emergence of pulse beetle, C. maculatus, indicated that 100 per cent adult mortality was recorded during the second, third and fourth months and significant difference was not observed among the exposure periods.Effect of cold treatment on oviposition of the pulse beetle, C. maculatus recorded with 100 per cent mortality and no significant difference was noticed among the exposure periods in which was observed. Effect of cold treatment on adult emergence of the pulse beetle, C. maculatus revealed 100 per cent adult mortality was observed in all the exposure period during the second, third and fourth months. Key words: Adult beetles,Bruchids,Black Gram,Cold treatment ,Oviposition,Sun drying I. -

Sprout Production in California

PUBLICATION 8060 Sprout Production in California WAYNE L. SCHRADER, University of California Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, San Diego County Sprouts have been used for food since before recorded history. Sprouts vary in texture and taste. Some are spicy (e.g., radish and onions), some are used in Asian foods (e.g., mung bean [Phaseolus aureus]), and others are delicate (e.g., alfalfa) and are UNIVERSITY OF used in salads and sandwiches to add texture. Vegetable sprouts grown for food are CALIFORNIA baby plants that are harvested just after germination. Various crop seeds may be Agriculture sprouted. The most common are adzuki, alfalfa, buckwheat, Brassica spp. (broccoli, and Natural Resources etc.), cabbage, clover, cress, garbanzo, green peas, lentils, mung bean, radish, rye, http://anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu sesame, wheat, and triticale. Production practices should provide appropriate ger- mination conditions, moisture, and temperatures that allow for the “harvesting” of the sprouts at their optimal eating quality. Production practices should also allow for efficient cleaning and packaging of sprouts. VARIETIES Mung bean seed are used to produce bean sprouts; some soybeans and adzuki beans are also used to produce bean sprouts. The preferred varieties are those that have smaller-sized seed. With small seed, the cotyledons and seed coats are less objec- tionable or are more easily removed from the finished product. The smallest-seeded varieties of mung bean are Oklahoma 12 and Oriental; larger-seeded types are Jumbo and Berken. Any small-seeded adzuki may be used for sprouts; a variety called Chinese Red Adzuki is sometimes substituted for adzuki bean even though it is not a true adzuki bean. -

The Evolution and Genomic Basis of Beetle Diversity

The evolution and genomic basis of beetle diversity Duane D. McKennaa,b,1,2, Seunggwan Shina,b,2, Dirk Ahrensc, Michael Balked, Cristian Beza-Bezaa,b, Dave J. Clarkea,b, Alexander Donathe, Hermes E. Escalonae,f,g, Frank Friedrichh, Harald Letschi, Shanlin Liuj, David Maddisonk, Christoph Mayere, Bernhard Misofe, Peyton J. Murina, Oliver Niehuisg, Ralph S. Petersc, Lars Podsiadlowskie, l m l,n o f l Hans Pohl , Erin D. Scully , Evgeny V. Yan , Xin Zhou , Adam Slipinski , and Rolf G. Beutel aDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152; bCenter for Biodiversity Research, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152; cCenter for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Arthropoda Department, Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, 53113 Bonn, Germany; dBavarian State Collection of Zoology, Bavarian Natural History Collections, 81247 Munich, Germany; eCenter for Molecular Biodiversity Research, Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, 53113 Bonn, Germany; fAustralian National Insect Collection, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia; gDepartment of Evolutionary Biology and Ecology, Institute for Biology I (Zoology), University of Freiburg, 79104 Freiburg, Germany; hInstitute of Zoology, University of Hamburg, D-20146 Hamburg, Germany; iDepartment of Botany and Biodiversity Research, University of Wien, Wien 1030, Austria; jChina National GeneBank, BGI-Shenzhen, 518083 Guangdong, People’s Republic of China; kDepartment of Integrative Biology, Oregon State -

G6PD Deficiency Food to Avoid Some of the Foods Commonly Eaten Around the World Can Cause People with G6PD Deficiency to Hemolyze

G6PD Deficiency Food To Avoid Some of the foods commonly eaten around the world can cause people with G6PD Deficiency to hemolyze. Some of these foods can be deadly (like fava beans). Some others can cause low level hemolysis, which means that red blood cells die, but not enough to cause the person to go to the hospital. Low level hemolysis over time can cause other problems, such as memory dysfunction, over worked spleen, liver and heart, and iron overload. Even though a G6PD Deficient person may not have a crises when consuming these foods, they should be avoided. • Fava beans and other legumes This list contains every legumes we could find, but there may be other names for them that we do not know about. Low level hemolysis is very hard to detect and can cause other problems, so we recommend the avoidance of all legumes. • Sulfites And foods containing them. Sulfites are used in a wide variety of foods, so be sure to check labels carefully. • Menthol And foods containing it. This can be difficult to avoid as toothpaste, candy, breath mints, mouth wash and many other products have menthol added to them. Mint from natural mint oils is alright to consume. • Artificial blue food coloring Other artificial food color can also cause hemolysis. Natural food color such as found in foods like turmeric or grapes is okay. • Ascorbic acid Artificial ascorbic acid commonly put in food and vitamins can cause hemolysis in large doses and should be avoided. It is put into so many foods that you can be getting a lot of Ascorbic Acid without realizing it. -

The Seed Coat of Phaseolus Vulgaris Interferes with the Development Of

Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências ISSN: 0001-3765 [email protected] Academia Brasileira de Ciências Brasil Silva, Luciana B.; Sales, Maurício P.; Oliveira, Antônia E. A.; Machado, Olga L. T.; Fernandes, Kátia V. S.; Xavier-Filho, José The seed coat of Phaseolus vulgaris interferes with the development of the cowpea weevil [Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae)] Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, vol. 76, núm. 1, março, 2004, pp. 57-65 Academia Brasileira de Ciências Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=32776106 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências (2004) 76(1): 57-65 (Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences) ISSN 0001-3765 www.scielo.br/aabc The seed coat of Phaseolus vulgaris interferes with the development of the cowpea weevil [Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae)] LUCIANA B. SILVA1, MAURÍCIO P. SALES2, ANTÔNIA E.A. OLIVEIRA1, OLGA L.T. MACHADO1, KÁTIA V.S. FERNANDES1 and JOSÉ XAVIER-FILHO1 1Laboratório de Química e Função de Proteínas e Peptídeos, Centro de Biociências e Biotecnologia, Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense, 28015-620 Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ, Brasil 2Departamento de Bioquímica, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brasil Manuscript received on August 21, 2003; accepted for publication on October 1, 2003; contributed by José Xavier-Filho* ABSTRACT We have confirmed here that the seeds of the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris, L.) do not support develop- ment of the bruchid Callosobruchus maculatus (F.), a pest of cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp] seeds.