Caughie, J. (2007) Authors and Auteurs: the Uses of Theory. In: Donald, J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Cinema in Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’

Cinema In Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’ Manuel Ramos Martínez Ph.D. Visual Cultures Goldsmiths College, University of London September 2013 1 I declare that all of the work presented in this thesis is my own. Manuel Ramos Martínez 2 Abstract Political names define the symbolic organisation of what is common and are therefore a potential site of contestation. It is with this field of possibility, and the role the moving image can play within it, that this dissertation is concerned. This thesis verifies that there is a transformative relation between the political name and the cinema. The cinema is an art with the capacity to intervene in the way we see and hear a name. On the other hand, a name operates politically from the moment it agitates a practice, in this case a certain cinema, into organising a better world. This research focuses on the audiovisual dynamism of the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’ and ‘people’ in contemporary cinemas. It is not the purpose of the argument to nostalgically maintain these old revolutionary names, rather to explore their efficacy as names-in-dispute, as names with which a present becomes something disputable. This thesis explores this dispute in the company of theorists and audiovisual artists committed to both emancipatory politics and experimentation. The philosophies of Jacques Rancière and Alain Badiou are of significance for this thesis since they break away from the semiotic model and its symptomatic readings in order to understand the name as a political gesture. Inspired by their affirmative politics, the analysis investigates cinematic practices troubled and stimulated by the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’, ‘people’: the work of Peter Watkins, Wang Bing, Harun Farocki, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub. -

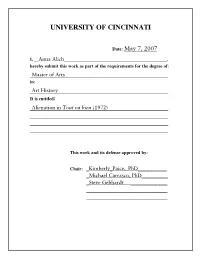

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 7, 2007 I, __Anna Alich_____________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: Alienation in Tout va bien (1972) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Kimberly_Paice, PhD___________ _Michael Carrasco, PhD__________ _Steve Gebhardt ______________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Alienation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972) A thesis presented to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Anna Alich May 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Jean-Luc Godard’s (b. 1930) Tout va bien (1972) cannot be considered a successful political film because of its alienated methods of film production. In chapter one I examine the first part of Godard’s film career (1952-1967) the Nouvelle Vague years. Influenced by the events of May 1968, Godard at the end of this period renounced his films as bourgeois only to announce a new method of making films that would reflect the au courant French Maoist politics. In chapter two I discuss Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group’s last film Tout va bien. This film displays a marked difference in style from Godard’s earlier films, yet does not display a clear understanding of how to make a political film of this measure without alienating the audience. In contrast to this film, I contrast Guy Debord’s (1931-1994) contemporaneous film The Society of the Spectacle (1973). As a filmmaker Debord successfully dealt with alienation in film. -

Um Cinema De Contrabando

1 Rio de Janeiro 01 a 20 de fevereiro São Paulo 02 a 20 de fevereiro Brasília 15 de fevereiro a 06 de março 2011 2 3 Expoente do movimento da Nouvelle Vague francesa, conhecido por sua obra bem-humorada, antiautoritária e criativa, o diretor francês Luc Moullet recebe retrospectiva completa no CCBB. Sua filmografia, premiada pelos mais importantes festivais internacionais, despertou admiração em cineastas como Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Marie Straub, Claire Dennis e Raoul Ruiz. Moullet acumula também destacada atividade como crítico, sendo seus textos reconhecidos como fundamentais para os novos cinemas que eclodiram na década de 1960 em países como França, República Tcheca (ex Tchecoslováquia), Hungria, Brasil, Polônia, entre outros. Ao realizar esta mostra, o Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil reafirma seu compromisso em oferecer à sociedade importantes nomes da cultura mundial, tornando acessíveis produções relevantes que permitem compreender a expressão audiovisual contemporânea. Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil 4 5 Na capa: As poltronas do cine Alcazar Luc Moullet durante as filmagens de As poltronas do cine Alcazar 6 7 As Contrabandistas Martin Scorsese define boa parte dos cineastas americanos como contrabandistas. Contrabando é fingir que cocaína é açúcar. Orson Welles faz isso quando disfarça A Marca da maldade de filme policial barato. John Cassavetes faz isso com A Morte de um bookmaker chinês. E Godard também, ao fingir que King Lear é uma adaptação fidedigna de Shakespeare. Eu mesmo fiz Une aventure de Billy le Kid passar por faroeste. O contrabando está no coração do cinema. Luc Moullet em Notre alpin quotidien - Entretien avec Luc Moullet, 2009 8 9 As Contrabandistas O amor ao cinema e a mania de ver filmes, aliás, estão entre os temas preferidos do cineasta-cinéfilo, que fez da afronta aos círculos tradicio- nais da cinefilia e do culto ao cinema um ofício. -

Le Conseil Général Partenaire Du Film Documentaire

« Dans le monde concret organisé par l’injustice et la terreur, qui voudrait voir confondre « populaire » avec « industriel », toute expression ne relevant pas du hurlement enragé ou du chant d’amour fou collabore à son aménagement et à son maintien ». Nicole Brenez (Abel Ferrara, le mal sans les fleurs, Cahiers du cinéma – Auteurs, 2008) - 3 - Remerciements Président du Festival : Étienne Butzbach le Granit, Le Balcon, l’Espace Gantner, le Centre Chorégraphique Déléguée générale, directrice artistique : Catherine Bizern National de Franche-Comté à Belfort, le LG’s bar, l’IUT Belfort- Délégué adjoint chargé de la coordination : Michèle Demange Montbéliard, l’UTBM, le cinéma Bel air, l’espace cinéma (Kur- Adjoint à la direction artistique, catalogue : Christian Borghino saal et Planoise), la Ville de Delle et Delle animation, le Nouveau Sélection de la compétition officielle Catherine: Bizern, Amélie Latina, Cezam, le BIJ, l’Espace Louis Jouvet, le C.I.E des 3 Chênes, Dubois, Jérôme Momcilovic Seven’Art, C’est dans la vallée, la Maison du tourisme du Territoire Henri François Imbert Coordination de la sélection et des journées professionnelles : de Belfort, les services de la Ville de Belfort et de la Communauté Aline Jelen Cécile Cadoux d’Agglomération Belfortaine et les Cahiers du cinéma, France Bleu Gilles Levy Recherche des copies : Caroline Maleville Belfort-Montbéliard, France Culture, France 3 Bourgogne Franche- Michel Plazanet Relations presse : Claire Viroulaud, assistée de Claire Liborio Comté, l’Humanité, les Inrockuptibles, -

Reflections on 'Rivette in Context'

ARTICLES · Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema · Vol. I · No. 1. · 2012 · 61-65 Reflections on ‘Rivette in Context’ Jonathan Rosenbaum ABSTRACT The author discusses two programmes that he curated under the title ‘Rivette in Context’, which took place at the National Film Theatre in London in August 1977 and at the Bleecker Street Cinema in New York in February 1979. Composed of 15 thematic programmes, the latter sets the films of Jacques Rivette in relation to other films, mostly from the US (including films by Mark Robson, Alfred Hitchcock, Jacques Tourneur, Fritz Lang, Otto Preminger). The essay notes and comments on the reactions of the US film critics to this programme, and also elaborates on the motivations that led him to the selection of films, which took as a reference the critical corpus elaborated by Rivette in Cahiers du cinéma alongside the influences that he had previously acknowledged in several interviews. Finally the article considers the impact of Henri Langlois’s programming method in the work of film-makers such as Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais or Luc Moullet, concluding that it generated a new critical space for writers, programmers and film-makers, based on the comparisons and rhymes between films. KEYWORDS Jacques Rivette, double programmes, American cinema, National Film Theatre, Bleecker Street Cinema, Henri Langlois, film criticism, thematic programmes, comparative cinema, montage. 61 REFLECTIONS ON ‘Rivette in ConteXT’ «Rivette in Context» had two separate Fuller, 1955); Hawks’ Monkey Business (1952); The incarnations, -

Meta-Cinematic Cultism: Between High and Low Culture Fátima Chinita Lisbon Polytechnic Institute, Theater and Film School, Portugal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE AVANCA provided by Repositório Científico do Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa Meta-cinematic Cultism: Between High and Low Culture Fátima Chinita Lisbon Polytechnic Institute, Theater and Film School, Portugal Abstract Nevertheless, both approaches describe the mechanisms of filmmaking; it is essentially the focus Meta-cinema can depict film viewers’ attitudes and the goals that change in each case, but filmson- towards cinema and their type of devotion for films. film tend to be more descriptive. As examples of the One subcategory of viewers - which I call meta- first variety one could mention The Man with the spectators - is highly specialized in its type of Movie Camera (1929, Dziga Vertov, USSR), and consumption, bordering on obsession. I contend that Contempt (1963, Jean-Luc Godard, FRA/ITA). As there are two main varieties of meta-cinematic examples of the second kind one can point to Sunset reception, not altogether incompatible with one Boulevard (1950, Billy Wilder, USA), and The Player another, despite their apparent differences. As both of (1992, Robert Altman, USA). Laurence Soroka (1983) them are depicted on meta-cinematic products, the proposes a synthesis between the two approaches, films themselves are the best evidence of my adopting the expression “Hollywood Modernism” to typology. My categories of film viewers are the refer to artefacts that obey a hybrid aesthetics: they ‘cinephile’, an elite prone to artistic militancy and the are simultaneously self-conscious about the form adoration of filmic masters; and the ‘fan’, a low culture (enunciation) and manifest a thematic reflexivity that consumer keen on certain filmic universes and their exposes the meanderings of filmmaking (7). -

20 Luc Moullet: 'Sam Fuller: in Marlowe's Footsteps'

20 Luc Moullet: 'Sam Fuller: In Marlowe's Footsteps' (,Sam Fuller - sur les brisees de Marlowe', Cahiers du Cinema 93, March 1959) Young American film directors have nothing at all to say, and Sam Fuller even less than the others. There is something he wants to do, and he does it naturally and effortlessly. That is not a shallow compliment: we have a strong aversion to would-be philosophers who get into making films in spite of what film is, and who just repeat in cinema the discoveries of the other arts, people who want to express interesting subjects with a certain artistic style. If you have something to say, say it, write it, preach it if you like, but don't come bothering us with it. Such an a priori judgment may seem surprising in an article on a director who admits to having very high ambitions, and who is the complete auteur of almost all his films. But it is precisely those who classify him among the intelligent screenwriters who do not like The Steel Helmet or reject Run of the Arrow on his behalf or, just as possibly, defend it for quite gratuitous reasons. Machiavelli and the cuckoo-clock On coherence. Of fourteen films, Fuller, a former journalist, devotes one to journalism; a former crime reporter, he devotes four to melodramatic thrillers; a former soldier, five to war. His four Westerns are related to the war films, since the perpetual struggle against the elements in the course of which man recognizes his dignity, which is the definition of pioneer life in the last century I is extended into our time only in the life of the soldier: that is why 'civilian life doesn't interest me' (Fixed Bayonets). -

Or the Making of French Film Ideology Laurent Jullier, Jean-Marc Leveratto

The Story of a Myth : The ”Tracking Shot in Kapò” or the Making of French Film Ideology Laurent Jullier, Jean-Marc Leveratto To cite this version: Laurent Jullier, Jean-Marc Leveratto. The Story of a Myth : The ”Tracking Shot in Kapò” or the Making of French Film Ideology. Mise au Point: Cahiers de l’AFECCAV, Association française des enseignants et chercheurs en cinéma et audio-visuel, 2016, 10.4000/map.2069. hal-03198994 HAL Id: hal-03198994 https://hal.univ-lorraine.fr/hal-03198994 Submitted on 15 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Mise au point Cahiers de l’association française des enseignants et chercheurs en cinéma et audiovisuel 8 | 2016 Chapelles et querelles des théories du cinéma The Story of a Myth : The “Tracking Shot in Kapò” or the Making of French Film Ideology L’Histoire d’un mythe : le « travelling de Kapo » ou la formation de l’idéologie française du film d'auteur Laurent Jullier et Jean-Marc Leveratto Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/map/2069 DOI: 10.4000/map.2069 ISSN: 2261-9623 Publisher Association française des enseignants et chercheurs en cinéma et audiovisuel Brought to you by Université de Lorraine Electronic reference Laurent Jullier et Jean-Marc Leveratto, “The Story of a Myth : The “Tracking Shot in Kapò” or the Making of French Film Ideology”, Mise au point [Online], 8 | 2016, Online since 01 April 2016, connection on 15 April 2021. -

The Cine-Tourist's Map of New Wave Paris

CHAPTER 6 The Cine-Tourist’s Map of New Wave Paris Roland-François Lack As I write, a project is under way at New York University (NYU) to produce a map-based app of New Wave Paris as an educational tool for students and cinephiles. For cine-tourists too, I hope. This essay was researched and drafted as I imagined what a map of New Wave Paris might be like, without the expectation that it could so soon be realised. An earlier, broader project called Cinemacity gave indications as to what a more general cine-touristic app-map of Paris might look like, and in part this essay is informed by New Wave-related mappings to be found on that site.1 Overall, however, what follows are hypotheses and deductions based on old-school location hunting, with an old map in hand – more specifi- cally, a 1962 ‘Indicateur des rues de Paris’ (Fig. 6.1): A necessary preliminary is to establish what we mean by New Wave – the when and the who. The broadest possible time frame stretches from the mid- 1950s to 1968. The filmmakers fall into five clear categories: (1) those asso- ciated with the Cahiers du Cinéma, not only the famous five (Chabrol, Godard, Rivette, Rohmer and Truffaut) but also several lesser-known critics turned filmmakers (among them Doniol-Valcroze, Givray, Kast, Moullet ...); (2) the Left Bank group, chiefly Marker, Resnais and Varda; (3) the cinéma- vérité filmmakers, Rouch above all but also, for one film at least, Reichenbach; (4) the unaffiliated, making a first film in the New Wave period, in a New Wave R.-F. -

Jean Marie Straub Y Danièle Huillet

JEAN-MARIE STRAUB Y DANIÈLE HUILLET jean�marie straub y danièle huillet HACER LA REVOLUCIÓN ES VOLVER A COLOCAR EN SU SITIO COSAS MUY ANTIGUAS PERO OLVIDADAS 11 77 INTRODUCCIÓN LA PALABRA SENSIBLE Manuel Asín y Chema González (A PROPÓSITO DE OBREROS, CAMPESINOS) 25 Jacques Rancière EL NUEVO CINE EN EL MUNDO Glauber Rocha 93 EL CANTO DE LA NATURALEZA DE LA NATURALEZA AL MITO: 33 LA CUESTIÓN DEL PAISAJE UNA TUMBA PARA EL OJO EN EL CINE DE STRAUB-HUILLET (PEDAGOGÍA STRAUBIANA) Santos Zunzunegui Serge Daney 127 43 NOMBRAR, RESISTIR LA ENORME PRESENCIA DE LOS MUERTOS DE LOS TÍTULOS EN EL CINE DE STRAUB – HUILLET Jean Narboni Manuel Ramos Martínez 55 UNA MORAL DE LA PERCEPCIÓN 145 (DE LA NUBE A LA RESISTENCIA, CINE [Y] POLÍTICA. DE STRAUB-HUILLET) «HOZ Y MARTILLO, CAÑONES, Serge Daney CAÑONES, ¡DINAMITA!» ENTREVISTA CON JEAN-MARIE STRAUB Y DANIÈLE HUILLET 65 François Albera NOCHE DE CINE, NOCHE DE ANIMALES DE CINE (A PROPÓSITO DE ANTÍGONA) 173 Peter Handke FILMOGRAFÍA Manuel Asín y Chema González INTRODUCCIÓN En este libro, hemos querido partir de un fragmento de un artículo del cineasta brasileño Glauber Rocha que nos parece uno de los mejores documentos de la emergencia de algunos de los principales cineastas y cinematografías de finales de los años sesenta. En fecha tan significativa como marzo de 1968, Rocha intenta resumir para los lectores brasileños de O Cruzeiro, un semanario carioca de gran tirada, un panorama de los cines «de vanguardia» de distintos países del mundo. La intención de Rocha era situar dentro de un contexto internacional el Cinema Novo brasileño, del que por aquel entonces él se había convertido en una espe- cie de emisario en Europa. -

June 2012 Anthology Film Archives Film Program, Volume 42 No

ANTHOLOGY FILM ARCHIVES April - June 2012 Anthology Film Archives Film Program, Volume 42 No. 2, April–June 2012 Anthology Film Archives Film Program is published quarterly by Anthology Film Archives, 32 Second Avenue, NY, NY 10003 Subscription is free with Membership to Anthology Film Archives, or $15/year for non-members. Cover artwork by Shingo Francis, 2012, all rights reserved. Staff Board of Directors Jonas Mekas, Artistic Director Jonas Mekas, President John Mhiripiri, Director Oona Mekas, Treasurer Stephanie Gray, Director of Development & Publicity John Mhiripiri, Secretary Wendy Dorsett, Director of Membership & Publications Barney Oldfi eld, Chair Jed Rapfogel, Film Programmer, Theater Manager Matthew Press Ava Tews, Administrative Assistant Arturas Zuokas Collections Staff Honorary Board Robert A. Haller, Library agnès b., Brigitte Cornand, Robert Gardner, Andrew Lampert, Curator of Collections Annette Michelson. In memoriam: Louise Bourgeois John Klacsmann, Archivist (1911–2010), Nam June Paik (1932-2006). Erik Piil, Digital Archivist Board of Advisors Theater Staff Richard Barone, Deborah Bell, Rachel Chodorov, Ben Tim Keane, Print Traffi c Coordinator & Head Manager Foster, Roselee Goldberg, Timothy Greenfi eld-Sanders, Bradley Eros, Theater Manager, Researcher Ali Hossaini, Akiko Iimura, Susan McGuirk, Sebastian Rachelle Rahme, Theater Manager Mekas, Sara L. Meyerson, Benn Northover, Izhar Craig Barclift, Assistant Theater Manager Patkin, Ted Perry, Ikkan Sanada, Lola Schnabel, Stella Schnabel, Ingrid Scheib-Rothbart, P. Adams Sitney, Projectionists Hedda Szmulewicz, Marvin Soloway. Ted Fendt, Carolyn Funk, Sarah Halpern, Daren Ho, Jose Ramos, Moira Tierney, Eva von Schweinitz, Tim White, Jacob Wiener. Composer in Residence Box Offi ce John Zorn Phillip Gerson, Rachael Guma, Kristin Hole, Nellie Killian, Lisa Kletjian, Marcine Miller, Feliz Solomon.