The Cine-Tourist's Map of New Wave Paris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

A355 | Contournement Ouest De Strasbourg

A355 | CONTOURNEMENT OUEST DE STRASBOURG Dossier de presse Édition de juin 2019 A355 - CONTOURNEMENT OUEST DE STRASBOURG UN PROJET POUR LE TERRITOIRE PLAN DE SITUATION 4 LE CONTOURNEMENT OUEST DE STRASBOURG EN CHIFFRES LA « CARTE D’IDENTITÉ » DU PROJET 8 D’AUTRES CHIFFRES POUR EN SAVOIR DAVANTAGE SUR LE PROJET 9 UN CHANTIER CRÉATEUR D’EMPLOIS, FAVORISANT L’INSERTION 9 LES ACTEURS UN PROJET INTÉGRALEMENT FINANCÉ PAR ARCOS 12 LE CALENDRIER 13 UN PROJET RÉALISÉ EN CONCERTATION AVEC LE TERRITOIRE DES ACTIONS CONCRÈTES, FRUITS DE LA CONCERTATION MENÉE AVEC LE TERRITOIRE PLANTER POUR ANTICIPER 15 ACCOMPAGNER LES EXPLOITANTS AGRICOLES 15 PRINCIPE DE L’AMÉNAGEMENT FONCIER 16 ZOOM SUR LES TRAVAUX UNE PRIORITÉ : ASSURER LES CONTINUITÉS ROUTIÈRES PENDANT LES TRAVAUX 17 LE SAVIEZ-VOUS ? 18 2 CONFIGURATIONS POSSIBLES POUR RÉTABLIR LES VOIRIES 20 FOCUS SUR LA CONSTRUCTION DE LA SECTION COUVERTE 22 FOCUS SUR LA CONSTRUCTION DU VIADUC DE VENDENHEIM 23 PRÉSERVER L’ENVIRONNEMENT : UN ENJEU MAJEUR, DES MESURES INÉDITES ET INNOVANTES BIODIVERSITÉ 25 LES MESURES COMPENSATOIRES : PLUS DE 1 300 HECTARES 27 UN CADRE RÉGLEMENTAIRE INÉDIT POUR UNE INFRASTRUCTURE DE CETTE AMPLEUR 27 FOCUS SUR LE GRAND HAMSTER 28 RESSOURCE EN EAU 29 UNE INNOVATION : LE BIODUC 30 UNE OPPORTUNITÉ POUR DÉCOUVRIR LA RICHESSE DE NOTRE PATRIMOINE L’ARCHÉOLOGIE PRÉVENTIVE 31 LES DIAGNOSTICS ARCHÉOLOGIQUES 31 LES FOUILLES ARCHÉOLOGIQUES 31 LA RECHERCHE ET LA VALORISATION 32 PROPOSER AU PLUS GRAND NOMBRE DE SUIVRE LE CHANTIER INFORMER LES USAGERS DES ROUTES EN TRAVAUX 35 UN SITE INTERNET POUR SE TENIR INFORMÉ 36 A355 - CONTOURNEMENT OUEST DE STRASBOURG UN PROJET POUR LE TERRITOIRE L’autoroute A355 offre de nombreux atouts pour le territoire strasbourgeois. -

Promenade Dans Le Parc Monceau

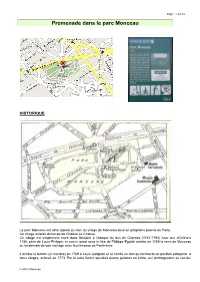

Page : 1 sur 16 Promenade dans le parc Monceau HISTORIQUE Le parc Monceau est ainsi appelé du nom du village de Monceau situé en périphérie proche de Paris. Ce village existait du temps de Charles Le Chauve. Ce village est simplement entré dans l’histoire à l’époque du duc de Chartres (1747-1793) futur duc d’Orléans 1785, père de Louis-Philippe, et connu aussi sous le titre de Philippe Egalité achète en 1769 la terre de Monceau au lendemain de son mariage avec la princesse de Penthièvre. Il achète le terrain (un hectare) en 1769 à Louis Colignon et lui confie en tant qu’architecte un pavillon octogonal, à deux étages, achevé en 1773. Par la suite furent ajoutées quatre galeries en étoile, qui prolongeaient au rez-de- Le Parc Monceau Page : 2 sur 16 chaussée quatre des pans, mais l'ensemble garda son unité. Colignon dessine aussi un jardin à la française c’est à dire arrangé de façon régulière et géométrique. Puis, entre 1773 et 1779, le prince décida d’en faire construire un autre plus vaste, dans le goût du jour, celui des jardins «anglo-chinois» qui se multipliaient à la fin du XVIIIe siècle dans la région parisienne notamment à Bagatelle, Ermenonville, au Désert de Retz, à Tivoli, et à Versailles. Le duc confie les plans à Louis Carrogis dit Carmontelle (1717-1806). Ce dernier ingénieur, topographe, écrivain, célèbre peintre et surtout portraitiste et organisateur de fêtes, décide d'aménager un jardin d'un genre nouveau, "réunissant en un seul Jardin tous les temps et tous les lieux ", un jardin pittoresque selon sa propre formule. -

General Interest

GENERAL INTEREST GeneralInterest 4 FALL HIGHLIGHTS Art 60 ArtHistory 66 Art 72 Photography 88 Writings&GroupExhibitions 104 Architecture&Design 116 Journals&Annuals 124 MORE NEW BOOKS ON ART & CULTURE Art 130 Writings&GroupExhibitions 153 Photography 160 Architecture&Design 168 Catalogue Editor Thomas Evans Art Direction Stacy Wakefield Forte Image Production BacklistHighlights 170 Nicole Lee Index 175 Data Production Alexa Forosty Copy Writing Cameron Shaw Printing R.R. Donnelley Front cover image: Marcel Broodthaers,“Picture Alphabet,” used as material for the projection “ABC-ABC Image” (1974). Photo: Philippe De Gobert. From Marcel Broodthaers: Works and Collected Writings, published by Poligrafa. See page 62. Back cover image: Allan McCollum,“Visible Markers,” 1997–2002. Photo © Andrea Hopf. From Allan McCollum, published by JRP|Ringier. See page 84. Maurizio Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari, “TP 35.” See Toilet Paper issue 2, page 127. GENERAL INTEREST THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART,NEW YORK De Kooning: A Retrospective Edited and with text by John Elderfield. Text by Jim Coddington, Jennifer Field, Delphine Huisinga, Susan Lake. Published in conjunction with the first large-scale, multi-medium, posthumous retrospective of Willem de Kooning’s career, this publication offers an unparalleled opportunity to appreciate the development of the artist’s work as it unfolded over nearly seven decades, beginning with his early academic works, made in Holland before he moved to the United States in 1926, and concluding with his final, sparely abstract paintings of the late 1980s. The volume presents approximately 200 paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints, covering the full diversity of de Kooning’s art and placing his many masterpieces in the context of a complex and fascinating pictorial practice. -

Proquest Dissertations

Filming in the Feminine Plural: The Ethnochoranic Narratives of Agnes Varda Lindsay Peters A Thesis in The Department of Film Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada September 2010 © Lindsay Peters, 2010 Library and Archives Bib!ioth6que et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-71098-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-71098-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

![Le Portique, 33 | 2014, “Straub !” [Online], Online Since 05 February 2016, Connection on 12 April 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3336/le-portique-33-2014-straub-online-online-since-05-february-2016-connection-on-12-april-2021-323336.webp)

Le Portique, 33 | 2014, “Straub !” [Online], Online Since 05 February 2016, Connection on 12 April 2021

Le Portique Revue de philosophie et de sciences humaines 33 | 2014 Straub ! Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/leportique/2735 DOI: 10.4000/leportique.2735 ISSN: 1777-5280 Publisher Association "Les Amis du Portique" Printed version Date of publication: 1 May 2014 ISSN: 1283-8594 Electronic reference Le Portique, 33 | 2014, “Straub !” [Online], Online since 05 February 2016, connection on 12 April 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/leportique/2735; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/leportique.2735 This text was automatically generated on 12 April 2021. Tous droits réservés 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Avant-Propos Autour des films Propos autour des films Le jamais vu (à propos des Dialogues avec Leucò) Jean-Pierre Ferrini À propos de Où gît votre sourire enfoui ? de Pedro Costa Mickael Kummer Autour d'Antigone Au sujet d’Antigone Barbara Ulrich Antigone s'arrête à Ségeste Olivier Goetz Autour d'Antigone Jean-Marie Straub À propos de la mort d'Empédocle Jean-Luc Nancy and Jean-Marie Straub Après la projection du film Anna Magdalena Bach Jacques Drillon and François Narboni Retour sur Chronique d’Anna Magdalena Bach par Jean-Marie Straub Jean-Marie Straub Rencontres avec Jean-Marie Straub après les projections Après Lothringen Jean-Marie Straub Après Sicilia Jean-Marie Straub Autour de O Somma Luce et de Corneille Jean-Marie Straub Après O Somma Luce et Corneille Jean-Marie Straub Le Portique, 33 | 2014 2 Après Chronique d’Anna Magdalena Bach Jean-Marie Straub Autour de trois films Jean-Marie Straub Après Othon Jean-Marie -

Paradoxes of the Nouvelle Vague

ARTICLES · Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema · Vol. I · No. 2. · 2013 · 77-82 Paradoxes of the Nouvelle Vague Marcos Uzal ABSTRACT This essay begins at the start of the magazine Cahiers du cinéma and with the film-making debut of five of its main members: François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette and Jean-Luc Godard. At the start they have shared approaches, tastes, passions and dislikes (above all, about a group of related film-makers from so-called ‘classical cinema’). Over the course of time, their aesthetic and political positions begin to divide them, both as people and in terms of their work, until they reach a point where reconciliation is not posible between the ‘midfield’ film-makers (Truffaut and Chabrol) and the others, who choose to control their conditions or methods of production: Rohmer, Rivette and Godard. The essay also proposes a new view of work by Rivette and Godard, exploring a relationship between their interest in film shoots and montage processes, and their affinities with various avant-gardes: early Russian avant-garde in Godard’s case and in Rivette’s, 1970s American avant-gardes and their European translation. KEYWORDS Nouvelle Vague, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, François Truffaut, radical, politics, aesthetics, montage. 77 PARADOXES OF THE NOUVELLE VAGUE In this essay the term ‘Nouvelle Vague’ refers that had emerged from it: they considered that specifically to the five film-makers in this group cinematic form should be explored as a kind who emerged from the magazine Cahiers du of contraband, using the classic art of mise-en- cinéma: Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, Jean-Luc scène rather than a revolutionary or modernist Godard, Claude Chabrol and François Truffaut. -

Cinema in Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’

Cinema In Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’ Manuel Ramos Martínez Ph.D. Visual Cultures Goldsmiths College, University of London September 2013 1 I declare that all of the work presented in this thesis is my own. Manuel Ramos Martínez 2 Abstract Political names define the symbolic organisation of what is common and are therefore a potential site of contestation. It is with this field of possibility, and the role the moving image can play within it, that this dissertation is concerned. This thesis verifies that there is a transformative relation between the political name and the cinema. The cinema is an art with the capacity to intervene in the way we see and hear a name. On the other hand, a name operates politically from the moment it agitates a practice, in this case a certain cinema, into organising a better world. This research focuses on the audiovisual dynamism of the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’ and ‘people’ in contemporary cinemas. It is not the purpose of the argument to nostalgically maintain these old revolutionary names, rather to explore their efficacy as names-in-dispute, as names with which a present becomes something disputable. This thesis explores this dispute in the company of theorists and audiovisual artists committed to both emancipatory politics and experimentation. The philosophies of Jacques Rancière and Alain Badiou are of significance for this thesis since they break away from the semiotic model and its symptomatic readings in order to understand the name as a political gesture. Inspired by their affirmative politics, the analysis investigates cinematic practices troubled and stimulated by the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’, ‘people’: the work of Peter Watkins, Wang Bing, Harun Farocki, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub. -

Rapport Général Tome III Annexe 20

N° 101 SÉNAT PREMIÈRE SESSION ORDINAIRE DE 1993 - 1994 Annexe au procès-verbal de la séance du 22 novembre 1993 . RAPPORT GÉNÉRAL <0 FAIT au. nom de la commission des Finances, du contrôle budgétaire et des comptes économiques de la Nation (1 ) sur le projet de loi de finances pour 1994 ADOPTÉ PAR L'ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE, Par M. Jean ARTHUIS , j ■ Sénateur , Rapporteur général. 1 TOME in LES MOYENS DES SERVICES ET LES DISPOSITIONS SPÉCIALES (Deuxième partie de la loi de finances) il } ANNEXE N° 20 ÉQUIPEMENT, TRANSPORTS ET TOURISME II. Transports : 2. Routes 3. Sécurité routière Rapporteur spécial : M. Paul LORIDANT (1 ) Cette commission est composée de : MM . Christian Poncelet, président ; Jean Cluzel , Paul Girod, Jean Clouet, Jean - Pierre Masseret, vice-présidents ; Jacques Oudin , Louis Perrein, François Trucy , Robert Vizet, secrétaires ; Jean Arthuis , rapporteur général ; Philippe Adnot, René Ballayer, Bernard Barbier, Claude Belot, Mme* Maryse Bergé-Lavigne , MM. Maurice Blin , Camille Cabana , Ernest Cartigny , Auguste Cazalet, Michel Charasse , Jacques Chaumont, Henri Collard, Maurice Couve de Murville, Pierre Croze, Jacques Delong, Mme Paulette Fost, MM . Henri Goetschy , Emmanuel Hamel, Alain Lambert, Tony Larue, Paul Loridant, Roland du Luart, Michel Manet , Philippe Marini , Michel Moreigne, Jacques Mossion, Bernard Pellarin, René Régnault, Michel Sergent , Jacques Sourdille , Henri Torre, René Trégouët, Jacques Valade. Voir les numéros : Assemblée nationale ( 10e législ.) : 536, 580, 585 et T.A.66 . Sénat : 100(1993-1994). Lois de finances . -2- SOMMAIRE Pages PRINCIPALES OBSERVATIONS -T. .... : 5 i CHAPITRE PREMIER : PRÉSENTATION GÉNÉRALE DES CRÉDITS il 1 . Les changements de structure 12 /> . " 2 . Le développement du réseau routier 13 3 . -

Château De La Muette 2, Rue André Pascal Paris 75016 28 -30 June 2004

OECD SHORT-TERM ECONOMIC STATISTICS EXPERT GROUP MEETING (STESEG) Château de la Muette 2, rue André Pascal Paris 75016 28 -30 June 2004 INFORMATION General 1. The Short-term Economic Statistics Expert Group (STESEG) meeting is scheduled to be held at the OECD headquarters at 2, rue André Pascal, Paris 75016, from Monday 28 June to Wednesday 30 June 2004. 2. The meeting will commence at 9.30am on Monday 28 June 2004 and will be held in Room 2 for the first two days and Room 6 on the third day. Registration and identification badges 3. All delegates are requested to register with the OECD Security Section and to obtain ID badges at the Reception Centre, located at 2, rue André Pascal, on the first morning of the meeting. It is advisable to arrive there no later than 9.00am; queues often build up just prior to 9.30am because of the number of meetings which start at that time. Please note you should bring some form of photo identification with you. 4. For identification and security reasons, participants are requested to wear their security badges at all times while inside the OECD complex. Immigration requirements 5. Delegates travelling on European Union member country passports do not require visas to enter France. All other participants should check with the relevant French diplomatic or consular mission on visa requirements. If a visa is required, it is your responsibility to obtain it before travelling to France. If you need a formal invitation to support your visa application please contact the Statistics Directorate well before the meeting. -

3.6.6 Schéma Directeur Cyclable De Valence-Romans Déplacements

3.6.6 Schéma Directeur Cyclable de Valence-Romans Déplacements Priorité 1 : Les itinéraires prioritaires, objectifs : la continuité cyclables inter et intra pôles centraux La liaison Valence-Romans (itinéraire n°1) est un axe majeur dans l’organisation du territoire. Elle répond aux déplacements Valence-Romans Déplacement réalise des préconisations techniques pour l’aménagement des voies cyclables et définit en effectués quotidiennement entre les deux principaux espaces urbains et les différentes zones d’activités avec notamment la étroite collaboration avec l’ensemble de ces partenaires des orientations et objectifs à atteindre. gare TGV sur la zone de Rovaltain. Afin d’obtenir un réseau cyclable continu et homogène sur l’ensemble du territoire, Valence Romans Déplacements a défini des itinéraires cyclables à aménager en priorité. Ces priorités pourront être affinées dans le cadre de la mise en œuvre du Priorité 2 : les itinéraires secondaires, objectifs : les continuités cyclables intra pôles secondaires Schéma, notamment en fonction des opportunités d’aménagements. Ces itinéraires ont pour vocation de relier les pôles secondaires (communes périurbaines). La majorité de ces itinéraires sont dédiés aux déplacements domicile/loisir avec notamment les itinéraires en projet de la Véloroute et voie verte (VVV) Vallée de l’Isère (itinéraire n°7), la VVV du Piedmont (itinéraire n°8) et la VVV de la vallée de l’Herbasse (itinéraire n°9). Priorité 3 : les itinéraires complémentaires, objectifs : les continuités cyclables inter pôles complémentaires Ces itinéraires sont complémentaires aux itinéraires cyclables secondaires. La majorité de ces itinéraires sont dédiés aux déplacements de loisirs Zone d’étude Zone d’étude Figure 75 : Schéma de principe des itinéraires cyclables (source : VRD) La liaison Valence-Romans (itinéraire n°1) concerne le carrefour des Couleures. -

Review of Elevator to the Gallows

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY Graduate Center 2006 Review of Elevator to the Gallows Michael Adams City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs/135 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Elevator to the Gallows (Criterion Collection, 4.25.2006) Louis Malle’s 1958 film is notable for introducing many of the elements that would soon become familiar in the work of the French New Wave directors. Elevator to the Gallows conveys the sense of an artist trying to present a reality not previously seen in film, but a reality constantly touched by artifice. The film is also notable for introducing Jeanne Moreau to the international film audience. Although she had been in movies for ten years, she had not yet shown the distinctive Moreau persona. Florence Carala (Moreau) and Julien Tavernier (Maurice Ronet) are lovers plotting to kill her husband, also his boss, the slimy arms dealer Simon (Jean Wall). The narrative’s uniqueness comes from the lovers never appearing together. The film opens with a phone conversation between them, and there are incriminating photos of the once-happy couple at the end. In between, Julien pulls off what he thinks is a perfect crime. When he forgets a vital piece of evidence, however, he becomes stuck in an elevator. Then his car is stolen for a joyride by Louis (Georges Poujouly), attempting some James Dean-like rebellious swagger, and his girlfriend, Veronique (Yori Bertin).