Jean-Luc Godard'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Eric Rohmer's Film Theory (1948-1953)

MARCO GROSOLI FILM THEORY FILM THEORY ERIC ROHMER’S FILM THEORY (1948-1953) IN MEDIA HISTORY IN MEDIA HISTORY FROM ‘ÉCOLE SCHERER’ TO ‘POLITIQUE DES AUTEURS’ MARCO GROSOLI ERIC ROHMER’S FILM THEORY ROHMER’S ERIC In the 1950s, a group of critics writing MARCO GROSOLI is currently Assistant for Cahiers du Cinéma launched one of Professor in Film Studies at Habib Univer- the most successful and influential sity (Karachi, Pakistan). He has authored trends in the history of film criticism: (along with several book chapters and auteur theory. Though these days it is journal articles) the first Italian-language usually viewed as limited and a bit old- monograph on Béla Tarr (Armonie contro fashioned, a closer inspection of the il giorno, Bébert 2014). hundreds of little-read articles by these critics reveals that the movement rest- ed upon a much more layered and in- triguing aesthetics of cinema. This book is a first step toward a serious reassess- ment of the mostly unspoken theoreti- cal and aesthetic premises underlying auteur theory, built around a recon- (1948-1953) struction of Eric Rohmer’s early but de- cisive leadership of the group, whereby he laid down the foundations for the eventual emergence of their full-fledged auteurism. ISBN 978-94-629-8580-3 AUP.nl 9 789462 985803 AUP_FtMh_GROSOLI_(rohmer'sfilmtheory)_rug16.2mm_v02.indd 1 07-03-18 13:38 Eric Rohmer’s Film Theory (1948-1953) Film Theory in Media History Film Theory in Media History explores the epistemological and theoretical foundations of the study of film through texts by classical authors as well as anthologies and monographs on key issues and developments in film theory. -

Paradoxes of the Nouvelle Vague

ARTICLES · Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema · Vol. I · No. 2. · 2013 · 77-82 Paradoxes of the Nouvelle Vague Marcos Uzal ABSTRACT This essay begins at the start of the magazine Cahiers du cinéma and with the film-making debut of five of its main members: François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette and Jean-Luc Godard. At the start they have shared approaches, tastes, passions and dislikes (above all, about a group of related film-makers from so-called ‘classical cinema’). Over the course of time, their aesthetic and political positions begin to divide them, both as people and in terms of their work, until they reach a point where reconciliation is not posible between the ‘midfield’ film-makers (Truffaut and Chabrol) and the others, who choose to control their conditions or methods of production: Rohmer, Rivette and Godard. The essay also proposes a new view of work by Rivette and Godard, exploring a relationship between their interest in film shoots and montage processes, and their affinities with various avant-gardes: early Russian avant-garde in Godard’s case and in Rivette’s, 1970s American avant-gardes and their European translation. KEYWORDS Nouvelle Vague, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, François Truffaut, radical, politics, aesthetics, montage. 77 PARADOXES OF THE NOUVELLE VAGUE In this essay the term ‘Nouvelle Vague’ refers that had emerged from it: they considered that specifically to the five film-makers in this group cinematic form should be explored as a kind who emerged from the magazine Cahiers du of contraband, using the classic art of mise-en- cinéma: Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, Jean-Luc scène rather than a revolutionary or modernist Godard, Claude Chabrol and François Truffaut. -

Cinema in Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’

Cinema In Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’ Manuel Ramos Martínez Ph.D. Visual Cultures Goldsmiths College, University of London September 2013 1 I declare that all of the work presented in this thesis is my own. Manuel Ramos Martínez 2 Abstract Political names define the symbolic organisation of what is common and are therefore a potential site of contestation. It is with this field of possibility, and the role the moving image can play within it, that this dissertation is concerned. This thesis verifies that there is a transformative relation between the political name and the cinema. The cinema is an art with the capacity to intervene in the way we see and hear a name. On the other hand, a name operates politically from the moment it agitates a practice, in this case a certain cinema, into organising a better world. This research focuses on the audiovisual dynamism of the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’ and ‘people’ in contemporary cinemas. It is not the purpose of the argument to nostalgically maintain these old revolutionary names, rather to explore their efficacy as names-in-dispute, as names with which a present becomes something disputable. This thesis explores this dispute in the company of theorists and audiovisual artists committed to both emancipatory politics and experimentation. The philosophies of Jacques Rancière and Alain Badiou are of significance for this thesis since they break away from the semiotic model and its symptomatic readings in order to understand the name as a political gesture. Inspired by their affirmative politics, the analysis investigates cinematic practices troubled and stimulated by the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’, ‘people’: the work of Peter Watkins, Wang Bing, Harun Farocki, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub. -

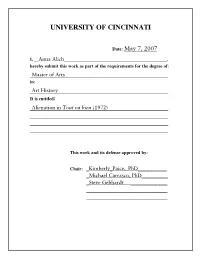

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 7, 2007 I, __Anna Alich_____________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: Alienation in Tout va bien (1972) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Kimberly_Paice, PhD___________ _Michael Carrasco, PhD__________ _Steve Gebhardt ______________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Alienation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972) A thesis presented to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Anna Alich May 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Jean-Luc Godard’s (b. 1930) Tout va bien (1972) cannot be considered a successful political film because of its alienated methods of film production. In chapter one I examine the first part of Godard’s film career (1952-1967) the Nouvelle Vague years. Influenced by the events of May 1968, Godard at the end of this period renounced his films as bourgeois only to announce a new method of making films that would reflect the au courant French Maoist politics. In chapter two I discuss Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group’s last film Tout va bien. This film displays a marked difference in style from Godard’s earlier films, yet does not display a clear understanding of how to make a political film of this measure without alienating the audience. In contrast to this film, I contrast Guy Debord’s (1931-1994) contemporaneous film The Society of the Spectacle (1973). As a filmmaker Debord successfully dealt with alienation in film. -

J. Edgar Hoover: the Man and the Secrets. Curt Gentry. Plume: New York, 1991

J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets. Curt Gentry. Plume: New York, 1991. P. 45 “Although Hoover’s memo did not explicitly state what should be kept in this file, ... they might also, and often did, include personal information, sometimes derogatory in nature ...” P. 51 “their contents [Hoover’s O/C files] included blackmail material on the patriarch of an American political dynasty, his sons, their wives, and other women; allegations of two homosexual arrests which Hoover leaked to help defeat a witty, urbane Democratic presidential candidate; the surveillance reports on one of America’s best-known first ladies and her alleged lovers, both male and female, white and black; the child-molestation documentation the director used to control and manipulate on of his Red-baiting proteges...” P. 214 “Even before [Frank] Murphy had been sworn in, Hoover had opened a file on his new boss. It was not without derogatory information. Like Hoover, Murphy was a lifelong bachelor . the former Michigan governor was a ‘notorious womanizer’.” P. 262 “Hoover believed that the morality of America was his business . ghost-written articles warning the public about the dangers of motels and drive-in ‘passion-pits’.” P. 302 “That the first lady [Eleanor Roosevelt] refused Secret Service protection convinced Hoover that she had something to hide. That she also maintained a secret apartment in New York’s Greenwich Village, where she was often visited by her friends but never by the president, served to reinforce the FBI director’s suspicions. What she was hiding, Hoover convinced himself, was a hyperactive sex life. -

Classic Auteur Theory

Part I Classic Auteur Theory COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL 1 A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema François Truffaut Francois Truffaut began his career as a fi lm critic writing for Cahiers du Cinéma beginning in 1953. He went on to become one of the most celebrated and popular directors of the French New Wave, beginning with his fi rst feature fi lm, Les Quatre cents coup (The Four Hundred Blows, 1959). Other notable fi lms written and directed by Truffaut include Jules et Jim (1962), The Story of Adele H. (1975), and L’Argent de Poche (Small Change, 1976). He also acted in some of his own fi lms, including L’Enfant Sauvage (The Wild Child, 1970) and La Nuit Américain (Day for Night, 1973). He appeared as the scientist Lacombe in Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Truffaut’s controversial essay, originally published in Cahiers du Cinéma in January 1954, helped launch the development of the magazine’s auteurist practice by rejecting the literary fi lms of the “Tradition of Quality” in favor of a cinéma des auteurs in which fi lmmakers like Jean Renoir and Jean Cocteau express a more personal vision. Truffaut claims to see no “peaceful co-existence between this ‘Tradition of Quality’ and an ‘auteur’s cinema.’ ” Although its tone is provocative, perhaps even sarcastic, the article served as a touchstone for Cahiers, giving the magazine’s various writers a collective identity as championing certain fi lmmakers and dismissing others. These notes have no other object than to attempt to These ten or twelve fi lms constitute what has been defi ne a certain tendency of the French cinema – a prettily named the “Tradition of Quality”; they force, by tendency called “psychological realism” – and to their ambitiousness, the admiration of the foreign press, sketch its limits. -

Burned Again the Critics

98 THE CRITICS on the border between north and south. If they took that city, they could cross the Loire and invade the rest of France. That was the situation which Joan’s voices eventually addressed. They told this illiterate peasant girl, who had never been more than a few miles from her village, to go to Orléans, raise the siege, and then take the Dauphin to Rheims to be crowned King Charles VII of France. In other words, they told her to end the Hundred Years’ War. A CRITIC AT LARGE She did so. Or, by inspiriting the 6 French soldiers at Orléans, she provided the turning point in the war. How Joan BURNED AGAIN managed to get to Charles, and persuade him to arm her, and then convince the The woman at the stake is worthy of another five hundred years of obsession. Valois captains that she should join the BY JOAN ACOCELLA charge at Orléans is still something of a mystery, but at that point the French forces were so beaten down that they OAN OF ARC movies, understand- man finishes, he does up his fly and says were almost willing to believe that a vir- ably, have always been low on to his mates, “Your turn.” Thus begins gin had been sent by God to deliver them. J sex, but in the newest entry, “The the career of Besson’s Joan of Arc. In And once Orléans was saved, under her Messenger: The Story of Joan of past ages, Joan has been seen as a mys- banner, many of the French came to see Arc,” by Luc Besson, the French action- tic, a saint, a national hero. -

Representations of Mental Illness in Women in Post-Classical Hollywood

FRAMING FEMININITY AS INSANITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF MENTAL ILLNESS IN WOMEN IN POST-CLASSICAL HOLLYWOOD Kelly Kretschmar, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Harry M. Benshoff, Major Professor Sandra Larke-Walsh, Committee Member Debra Mollen, Committee Member Ben Levin, Program Coordinator Alan B. Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, Television and Film Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kretschmar, Kelly, Framing Femininity as Insanity: Representations of Mental Illness in Women in Post-Classical Hollywood. Master of Arts (Radio, Television, and Film), May 2007, 94 pp., references, 69 titles. From the socially conservative 1950s to the permissive 1970s, this project explores the ways in which insanity in women has been linked to their femininity and the expression or repression of their sexuality. An analysis of films from Hollywood’s post-classical period (The Three Faces of Eve (1957), Lizzie (1957), Lilith (1964), Repulsion (1965), Images (1972) and 3 Women (1977)) demonstrates the societal tendency to label a woman’s behavior as mad when it does not fit within the patriarchal mold of how a woman should behave. In addition to discussing the social changes and diagnostic trends in the mental health profession that define “appropriate” female behavior, each chapter also traces how the decline of the studio system and rise of the individual filmmaker impacted the films’ ideologies with regard to mental illness and femininity. Copyright 2007 by Kelly Kretschmar ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 1 Historical Perspective ........................................................................ 5 Women and Mental Illness in Classical Hollywood ............................... -

How the FBI Used a Gossip Columnist to Smear a Movie Star | Film | the Guardian

10/23/2018 How the FBI used a gossip columnist to smear a movie star | Film | The Guardian How the FBI used a gossip columnist to smear a movie star Duncan Campbell on a story that is only now emerging after 30 years Duncan Campbell Mon 22 Apr 2002 12.16 EDT More than 30 years ago, a small item appeared in a gossip column in the Los Angeles Times which suggested that a prominent American actress, who was married to a well-known European, was expecting the child of a leading Black Panther. The story was taken up by Newsweek, which identified the actress as Jean Seberg and her husband as Romain Gary, the French writer and diplomat. The Black Panther was Ray "Masai" Hewitt, the party's minister of information. Seberg was deeply upset by the story, gave birth prematurely and the child died after two days. The actress later committed suicide having never, according to her friends, fully recovered. Now, finally, the whole story of how a malicious and untrue story was successfully planted by the FBI and its director J Edgar Hoover is emerging. Seberg was an unknown teenage student from Iowa when she was chosen by director Otto Preminger to play the title role in the 1957 film of Saint Joan. Although it was not a hit, Seberg went on to find critical success in such films as Breathless, Lilith and Bonjour Tristesse. She also appeared in the 50s British comedy, The Mouse That Roared. During the 60s, she married Gary, and became increasingly involved in radical American politics, most notably as a supporter of the Black Panther party, which Hoover was then describing as the greatest threat to internal security in the US. -

The Cahiers Du Cinema and the French Nouvelle Vague

Journalists turned Cinematographers: The Cahiers du Cinema and the French Nouvelle Vague An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) By Rebecca 1. Berfanger Ball State University Muncie, Indiana December 2000 Graduation: December 2000 ~eoll T'leSfS l-D ;:,147/1 Abstract ,z..tf - ~OO(., Journalists turned cinematographers: Cahiers du Cinema and the Nouvelle Vague is a "rA7 reflection of the so called French ''New Wave" cinema and how the Cahiers, one of the most influential film magazines of any language, has helped to shape modem cinema in some way. It reflects the age-old conflict between movie studios and independent filmmakers, where content and substance are judged against big name stars and pay checks. The four directors specifically mentioned in this paper are among the most influential as they were with the magazine early on and made movies in the late 1950s to the early 1970s, the height of the ''New Wave." Truff'aut has always captured themes of childhood and innocence, Godard has political themes (while claiming to be "unpolitical"), Resnais made documentaries films based on literature, and Rohmer demonstrated provincial life and morals. - Acknowledgements I had more than a few helpers with this project. I would like to thank Richard Meyer for being my first advisor and helping me focus on the subject with ideas for references and directors. I would also like to thank every French teacher I have had at Ball State who has furthered my appreciation of the French language and French culture, what this paper is more or less all about. I would especially like to thank James Hightower, my second and final advisor for all of his support and encouragement from beginning to end by loaning me his books and editing capabilities. -

Jean-Luc Godard: Le Weekend

Works out his thinking in front of an audience Jean-Luc Godard: Analysis of class struggle Post-war realism Le Weekend Materialism French "Tradition of Quality" Africans & Algerians Historical Context Renewed access to Hollywood Film As Politics French Revolution: Liberty, Growth of Parisian film clubs & Equality, Fraternity. What if one criticism: Cahiers du cinema dominates the others? Young critics flock to "Primitivism" and political/social Cinemateque Director's cinema evolution. Corinne, Roland, Joseph Balsamo, St. Just, Emile High level film culture Rank directors in terms of Prescription: Revolution? Cahiers du cinema Bronte, Tom Thumb personal expressiveness Politique des auteurs: Critique, deconstruction of Long takes & tableau images Auteur Theory Directorial identity may be in narrative opposition to genre Sound & music Film language Discovery & promotion of "B- film" directors Intertitles, commentary & Issues Truffaut, Godard, Resnais, punning Rohmer, others Political theater & slapstick Godard's "Breathless" & Truffaut's "400 Blows" Distantiation techniques Nouvelle Vague Characterization & historical Camera-stylo: director's cinema personages Fiction >< Documentary "Little Movies" End title: "End of cinema" Breathless, 1960 Pre-War intellectualism, identity Vivre sa vie, 1962 50s consumerism Masculin, féminin, 1966 Godard: Nouvelle Vague Americanization to Dziga Vertov Group Weekend, 1967 Conservative French President Politics & Culture in Charles DeGualle: "Guallism" Radical films and exhibition France Reaction parallels "Hippie" practices, often video, after '68 movement in US, but more political, intellectual, social Model of socialist esthetics Semiotics: seeing culture as a language May, 1968: Students shut down Brecht translated Paris; decade of radicalization into French in 50s Language IS culture; culture IS follows language Art should promote social Ideology embedded in language change, not reinforce Structuralism, bourgeois values Berthold Brecht Deconstruction, etc.