20 Luc Moullet: 'Sam Fuller: in Marlowe's Footsteps'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

9782873404178 01.Pdf

SOMMAIRE Jean-François Rauger : La douceur Fuller L’ŒUVRE Thanatos Pierre Gabaston. La fureur Fuller Serge Chauvin. Crever l’écran. Une esthétique du surgissement Sarah Ohana. Faire face. À propos du style de Samuel Fuller Laurent Le Forestier. Samuel Fuller, cinéaste responsable Jean-Marie Samocki. Le chaos comme le chant. Samuel Fuller metteur en son Éros Murielle Joudet. La violence en partage Patrice Rollet. L’autre visage de la fureur. Érotique de Fuller Figures humaines Sergio Toffetti. Le jaune, le rouge, le noir et le blanc Chris Fujiwara. Les visages asiatiques de Samuel Fuller Jean-Marie Samocki. Le vieillissement de Lee Marvin. It Tolls for Thee / The Big Red One Simon Laperrière. Une grande mêlée. Les romans de Samuel Fuller LES FILMS Gilles Esposito. L’enfer du développement. Samuel Fuller scénariste Marcos Uzal. La Passion du traître. I Shot Jesse James / J’ai tué Jesse James Laura Laufer. L’Amour, vaste territoire The Baron of Arizona / Le Baron de l’Ari- zona Mathieu Macheret. Le Théâtre des opérations. The Steel Hemlet / J’ai vécu l’en- fer de Corée et Fixed Bayonets !/Baïonnette au canon Bernard Eisenschitz. Park Row / Violence à Park Row Murielle Joudet. Pickpocket. Pickup on South Street / Le Port de la drogue Samuel Bréan. Anatomie d’un mensonge. Le doublage de Pickup on South Street Jean-François Rauger. Le Sous-marin et les Rouges. Hell and High Water / Le Démon des eaux troubles The Steel Helmet. Egdardo Cozarinsky. House of Bamboo / La Maison de Bambou Bernard Benoliel. Fuller, l’attendrisseur. Run of the Arrow / Le Jugement des Jean-François Rauger flèches Jean-François Rauger. -

January 27, 2009 (XVIII:3) Samuel Fuller PICKUP on SOUTH STREET (1953, 80 Min)

January 27, 2009 (XVIII:3) Samuel Fuller PICKUP ON SOUTH STREET (1953, 80 min) Directed and written by Samuel Fuller Based on a story by Dwight Taylor Produced by Jules Schermer Original Music by Leigh Harline Cinematography by Joseph MacDonald Richard Widmark...Skip McCoy Jean Peters...Candy Thelma Ritter...Moe Williams Murvyn Vye...Captain Dan Tiger Richard Kiley...Joey Willis Bouchey...Zara Milburn Stone...Detective Winoki Parley Baer...Headquarters Communist in chair SAMUEL FULLER (August 12, 1912, Worcester, Massachusetts— October 30, 1997, Hollywood, California) has 53 writing credits and 32 directing credits. Some of the films and tv episodes he directed were Street of No Return (1989), Les Voleurs de la nuit/Thieves After Dark (1984), White Dog (1982), The Big Red One (1980), "The Iron Horse" (1966-1967), The Naked Kiss True Story of Jesse James (1957), Hilda Crane (1956), The View (1964), Shock Corridor (1963), "The Virginian" (1962), "The from Pompey's Head (1955), Broken Lance (1954), Hell and High Dick Powell Show" (1962), Merrill's Marauders (1962), Water (1954), How to Marry a Millionaire (1953), Pickup on Underworld U.S.A. (1961), The Crimson Kimono (1959), South Street (1953), Titanic (1953), Niagara (1953), What Price Verboten! (1959), Forty Guns (1957), Run of the Arrow (1957), Glory (1952), O. Henry's Full House (1952), Viva Zapata! (1952), China Gate (1957), House of Bamboo (1955), Hell and High Panic in the Streets (1950), Pinky (1949), It Happens Every Water (1954), Pickup on South Street (1953), Park Row (1952), Spring (1949), Down to the Sea in Ships (1949), Yellow Sky Fixed Bayonets! (1951), The Steel Helmet (1951), The Baron of (1948), The Street with No Name (1948), Call Northside 777 Arizona (1950), and I Shot Jesse James (1949). -

Cinema in Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’

Cinema In Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’ Manuel Ramos Martínez Ph.D. Visual Cultures Goldsmiths College, University of London September 2013 1 I declare that all of the work presented in this thesis is my own. Manuel Ramos Martínez 2 Abstract Political names define the symbolic organisation of what is common and are therefore a potential site of contestation. It is with this field of possibility, and the role the moving image can play within it, that this dissertation is concerned. This thesis verifies that there is a transformative relation between the political name and the cinema. The cinema is an art with the capacity to intervene in the way we see and hear a name. On the other hand, a name operates politically from the moment it agitates a practice, in this case a certain cinema, into organising a better world. This research focuses on the audiovisual dynamism of the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’ and ‘people’ in contemporary cinemas. It is not the purpose of the argument to nostalgically maintain these old revolutionary names, rather to explore their efficacy as names-in-dispute, as names with which a present becomes something disputable. This thesis explores this dispute in the company of theorists and audiovisual artists committed to both emancipatory politics and experimentation. The philosophies of Jacques Rancière and Alain Badiou are of significance for this thesis since they break away from the semiotic model and its symptomatic readings in order to understand the name as a political gesture. Inspired by their affirmative politics, the analysis investigates cinematic practices troubled and stimulated by the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’, ‘people’: the work of Peter Watkins, Wang Bing, Harun Farocki, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub. -

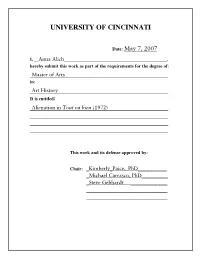

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 7, 2007 I, __Anna Alich_____________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: Alienation in Tout va bien (1972) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Kimberly_Paice, PhD___________ _Michael Carrasco, PhD__________ _Steve Gebhardt ______________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Alienation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972) A thesis presented to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Anna Alich May 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Jean-Luc Godard’s (b. 1930) Tout va bien (1972) cannot be considered a successful political film because of its alienated methods of film production. In chapter one I examine the first part of Godard’s film career (1952-1967) the Nouvelle Vague years. Influenced by the events of May 1968, Godard at the end of this period renounced his films as bourgeois only to announce a new method of making films that would reflect the au courant French Maoist politics. In chapter two I discuss Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group’s last film Tout va bien. This film displays a marked difference in style from Godard’s earlier films, yet does not display a clear understanding of how to make a political film of this measure without alienating the audience. In contrast to this film, I contrast Guy Debord’s (1931-1994) contemporaneous film The Society of the Spectacle (1973). As a filmmaker Debord successfully dealt with alienation in film. -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

Shadows of American Popular Culture Syllabus/Handbook 1

Shadows of American Popular Culture Syllabus/Handbook El Camino College Professor Maria A. Brown Office: MBBM 137 Office Hours: M-F 8:30 a.m. – 9:30 a.m. E-mail: [email protected] Website Domain: www.journeytohistory.com Washington Day College Closed February 21, 2011 Spring Recess College Closed April 9-April 15, 2011 Memorial Day Campus Closed May 30, 2011 The Last day to drop from class with a “W” grade is Friday, May 13, 2011. It is the student’s responsibility to process an official withdrawal from class. Failure to do so may result in a letter grade of A through F. A student may drop a class or classes within the refund period and add another class or classes using the fees already paid. If a student drops after the refund deadline, payment of fees for the classes is forfeited. Any added class will require additional fees. A student may drop a class before the refund deadline and add a class with no additional fees. If a student drops a class after the refund deadline in order to add the same class at a different time, date instructor, the student must request a lateral transfer or level transfer from both instructors. All transfers are processed through the Admissions Office. (See page 5 of the ECC Schedule of Classes, Spring, 2011) The semester ends Friday, June 10, 2011 Note: Please be advised that students are expected to follow the campus policy on student conduct which can be found in the ECC Campus Catalog. In this course students are expected to comply with the following: 1. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

Complete Film Noir

COMPLETE FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1965) Page 1 of 18 CONSENSUS FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1959) (1960-1965) dThe idea for a COMPLETE FILM NOIR LIST came to me when I realized that I was “wearing out” a then recently purchased copy of the Film Noir Encyclopedia, 3rd edition. My initial plan was to make just a list of the titles listed in this reference so I could better plan my film noir viewing on AMC (American Movie Classics). Realizing that this plan was going to take some keyboard time, I thought of doing a search on the Internet Movie DataBase (here after referred to as the IMDB). By using the extended search with selected criteria, I could produce a list for importing to a text editor. Since that initial list was compiled almost twenty years ago, I have added additional reference sources, marked titles released on NTSC laserdisc and NTSC Region 1 DVD formats. When a close friend complained about the length of the list as it passed 600 titles, the idea of producing a subset list of CONSENSUS FILM NOIR was born. Several years ago, a DVD producer wrote me as follows: “I'd caution you not to put too much faith in the film noir guides, since it's not as if there's some Film Noir Licensing Board that reviews films and hands out Certificates of Authenticity. The authors of those books are just people, limited by their own knowledge of and access to films for review, so guidebooks on noir are naturally weighted towards the more readily available studio pictures, like Double Indemnity or Kiss Me Deadly or The Big Sleep, since the many low-budget B noirs from indie producers or overseas have mostly fallen into obscurity.” There is truth in what the producer says, but if writers of (film noir) guides haven’t seen the films, what chance does an ordinary enthusiast have. -

Caughie, J. (2007) Authors and Auteurs: the Uses of Theory. In: Donald, J

Caughie, J. (2007) Authors and auteurs: the uses of theory. In: Donald, J. and Renov, M. (eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Film Studies. Sage, London, UK, pp. 408-423. ISBN 9780761943266 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/3787/ Deposited on: 26 February 2010 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 Authors and auteurs: the uses of theory John Caughie You know there’s a lot of detail in this movie; it’s absolutely essential because these little nuances enrich the over-all impact and strengthen the picture…. At the beginning of the film we show Rod Taylor in the bird shop. He catches the canary that has escaped from its cage, and after putting it back, he says to Tippi Hedren, ‘I’m putting you back in your gilded cage, Melanie Daniels’. I added that sentence during the shooting because I felt it added to her characterization as a wealthy, shallow playgirl. And later on, when the gulls attack the village, Melanie Daniels takes refuge in a glass telephone booth and I show her as a bird in a cage. This time it isn’t a gilded cage, but a cage of misery, and it’s also the beginning of her ordeal by fire, so to speak. It’s a reversal of the age-old conflict between men and birds. Here the humans are in cages, and the birds are on the outside. When I shoot something like that, I hardly think the public is likely to notice it. – Alfred Hitchcock on The Birds (Truffaut, 1985: 285) Returning to auteurism and authorship after a decent interval, I am struck by two contradictory perceptions: first, that the auteur seems to have disappeared from the centre of theoretical debate in Film Studies; second, that this disappearance may in fact be an illusion and that the grave to which we consigned him – and, by implication, her – is, in fact, empty. -

Le Port De La Drogue, Samuel Fuller (1953)

Le Port de la drogue, Samuel Fuller (1953) Le début de l’histoire Dans le métro de New York, un pickpocket, Skip McCoy, vole dans le sac d’une femme un portefeuille contenant un microfilm destiné à des agents communistes. Candy ignore qu’elle est suivie par la police, tout comme elle ignore le contenu exact de ce qu’elle transporte : elle accomplit cette mission pour son amant, Joey, un espion communiste. Lorsque le larcin est découvert, les ennuis commencent pour tout le monde, dans un univers mêlant à la fois la petite pègre des bas-fonds de l’Hudson River, la police fédérale et les espions en tout genre. Fiche technique Scénario : Samuel Fuller, d’après une histoire de Dwight Taylor Production : Fox Photographie : Joe MacDonald Musique : Leigh Harline Interprétation : Richard Widmark …………………. Skip McCoy Jean Peters…………………............. Candy Thelma Ritter ……………………... Moe Samuel Fuller Né en 1911 à Worcester, Samuel Fuller est, à dix-sept ans, le plus jeune reporter affecté aux affaires criminelles du New York Journal . Cette expérience lui inspire plusieurs romans, puis des scénarios. De 1942 à 1945, il fait la guerre en Europe et en Afrique dans la célèbre première division d’infanterie, appelée la Big Red One. Par la suite, la guerre sera l’un des thèmes majeurs de son œuvre cinématographique. Sa première réalisation, I Shot Jesse James , date de 1949. Suivront vingt-deux autres films, parmi lesquels on peut citer : The Steel Helmet (J’ai vécu l’enfer de Corée , 1950), Pick Up On South Street ( Le Port de la drogue , 1953), House of Bamboo (1955), Run of the Arrow ( Le Jugement des flèches , 1957), Forty Guns ( Quarante Tueurs , 1957), Shock Corridor (1963), The Naked Kiss ( Police spéciale , 1965), enfin The Big Red One (Au-delà de la gloire , 1979), projet qu’il avait mûri pendant plus de trente ans. -

World War Ii and Us Cinema

ABSTRACT Title of Document: WORLD WAR II AND U.S. CINEMA: RACE, NATION, AND REMEMBRANCE IN POSTWAR FILM, 1945-1978 Robert Keith Chester, Ph.D., 2011 Co-Directed By: Dr. Gary Gerstle, Professor of History, Vanderbilt University Dr. Nancy Struna, Professor of American Studies, University of Maryland, College Park This dissertation interrogates the meanings retrospectively imposed upon World War II in U.S. motion pictures released between 1945 and the mid-1970s. Focusing on combat films and images of veterans in postwar settings, I trace representations of World War II between war‘s end and the War in Vietnam, charting two distinct yet overlapping trajectories pivotal to the construction of U.S. identity in postwar cinema. The first is the connotations attached to U.S. ethnoracial relations – the presence and absence of a multiethnic, sometimes multiracial soldiery set against the hegemony of U.S. whiteness – in depictions of the war and its aftermath. The second is Hollywood‘s representation (and erasure) of the contributions of the wartime Allies and the ways in which such images engaged with and negotiated postwar international relations. Contrary to notions of a ―good war‖ untainted by ambiguity or dissent, I argue that World War II gave rise to a conflicted cluster of postwar meanings. At times, notably in the early postwar period, the war served as a progressive summons to racial reform. At other times, the war was inscribed as a historical moment in which U.S. racism was either nonexistent or was laid permanently to rest. In regard to the Allies, I locate a Hollywood dialectic between internationalist and unilateralist remembrances.