REFORMING POLICING André Douglas Pond Cummings* INTRODUCTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Systemic Racism, Police Brutality of Black People, and the Use of Violence in Quelling Peaceful Protests in America

SYSTEMIC RACISM, POLICE BRUTALITY OF BLACK PEOPLE, AND THE USE OF VIOLENCE IN QUELLING PEACEFUL PROTESTS IN AMERICA WILLIAMS C. IHEME* “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” —Martin Luther King Jr Abstract: The Trump Administration and its mantra to ‘Make America Great Again’ has been calibrated with racism and severe oppression against Black people in America who still bear the deep marks of slavery. After the official abolition of slavery in the second half of the nineteenth century, the initial inability of Black people to own land, coupled with the various Jim Crow laws rendered the acquired freedom nearly insignificant in the face of poverty and hopelessness. Although the age-long struggles for civil rights and equal treatments have caused the acquisition of more black-letter rights, the systemic racism that still perverts the American justice system has largely disabled these rights: the result is that Black people continue to exist at the periphery of American economy and politics. Using a functional approach and other types of approach to legal and sociological reasoning, this article examines the supportive roles of Corporate America, Mainstream Media, and White Supremacists in winnowing the systemic oppression that manifests largely through police brutality. The article argues that some of the sustainable solutions against these injustices must be tackled from the roots and not through window-dressing legislation, which often harbor the narrow interests of Corporate America. Keywords: Black people, racism, oppression, violence, police brutality, prison, bail, mass incarceration, protests. Summary: 1. INTRODUCTION: SLAVE TRADE AS THE ENTRY POINT OF SYSTEMIC RACISM. -

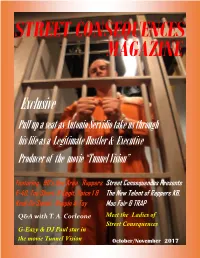

G-Eazy & DJ Paul Star in the Movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 in the BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED

STREET CONSEQUENCES MAGAZINE Exclusive Pull up a seat as Antonio Servidio take us through his life as a Legitimate Hustler & Executive Producer of the movie “Tunnel Vision” Featuring 90’s Bay Area Rappers Street Consequences Presents E-40, Too Short, B-Legit, Spice 1 & The New Talent of Rappers KB, Keak Da Sneak, Rappin 4-Tay Mac Fair & TRAP Q&A with T. A. Corleone Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences G-Eazy & DJ Paul star in the movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 IN THE BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED October/November 2017 2 October /November 2017 Contents Publisher’s Word Exclusive Interview with Antonio Servidio Featuring the Bay Area Rappers Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences Street Consequences presents new talent of Rappers October/November 2017 3 Publisher’s Words Street Consequences What are the Street Consequences of today’s hustling life- style’s ? Do you know? Do you have any idea? Street Con- sequences Magazine is just what you need. As you read federal inmates whose stories should give you knowledge on just what the street Consequences are. Some of the arti- cles in this magazine are from real people who are in jail because of these Street Consequences. You will also read their opinion on politics and their beliefs on what we, as people, need to do to chance and make a better future for the up-coming youth of today. Stories in this magazine are from big timer in the games to small street level drug dealers and regular people too, Hopefully this magazine will open up your eyes and ears to the things that are going on around you, and have to make a decision that will make you not enter into the game that will leave you dead or in jail. -

UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS of LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS in HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 By

ON THE BEAT: UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS IN HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 by Francesca A. Keesee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science Conflict Analysis and Resolution Master of Arts Conflict Resolution and Mediterranean Security Committee: ___________________________________________ Chair of Committee ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Graduate Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA University of Malta Valletta, Malta On the Beat: Understanding Portrayals of Law Enforcement Officers in Hip-hop Lyrics Since 2009 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science at George Mason University and Master of Arts at the University of Malta by Francesca A. Keesee Bachelor of Arts University of Virginia, 2015 Director: Juliette Shedd, Professor School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia University of Malta Valletta, Malta Copyright 2016 Francesca A. Keesee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to all victims of police brutality. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever grateful to my best friend, partner in crime, and husband, Patrick. -

Murder-Suicide Ruled in Shooting a Homicide-Suicide Label Has Been Pinned on the Deaths Monday Morning of an Estranged St

-* •* J 112th Year, No: 17 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents Murder-suicide ruled in shooting A homicide-suicide label has been pinned on the deaths Monday morning of an estranged St. Johns couple whose divorce Victims had become, final less than an hour before the fatal shooting. The victims of the marital tragedy were: *Mrs Alice Shivley, 25, who was shot through the heart with a 45-caliber pistol bullet. •Russell L. Shivley, 32, who shot himself with the same gun minutes after shooting his wife. He died at Clinton Memorial Hospital about 1 1/2 hqurs after the shooting incident. The scene of the tragedy was Mrsy Shivley's home at 211 E. en name, Alice Hackett. Lincoln Street, at the corner Police reconstructed the of Oakland Street and across events this way. Lincoln from the Federal-Mo gul plant. It happened about AFTER LEAVING court in the 11:05 a.m. Monday. divorce hearing Monday morn ing, Mrs Shivley —now Alice POLICE OFFICER Lyle Hackett again—was driven home French said Mr Shivley appar by her mother, Mrs Ruth Pat ently shot himself just as he terson of 1013 1/2 S. Church (French) arrived at the home Street, Police said Mrs Shlv1 in answer to a call about a ley wanted to pick up some shooting phoned in fromtheFed- papers at her Lincoln Street eral-Mogul plant. He found Mr home. Shivley seriously wounded and She got out of the car and lying on the floor of a garage went in the front door* Mrs MRS ALICE SHIVLEY adjacent to -• the i house on the Patterson got out of-'the car east side. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Research Evaluation of the City of Columbus' Response to the 2020

Research Evaluation of the City of Columbus’ Response to the 2020 Summer Protests Trevor L. Brown, Ph.D. Carter M. Stewart, J.D. John Glenn College of Public Affairs, The Ohio State University Table of Contents 1 Overview 5 Executive Summary of Findings and Recommendations 11 Context: Systemic Racism, Policing and Protests 17 Columbus Context and Timeline of Key Events 25 Chapter 1: Citizen-Police Relations and the Protests; Community Member Trauma 32 Chapter 2: City and Columbus Division of Police Leadership and Incident Command 41 Chapter 3: Policy and Training 52 Chapter 4: Officer Wellness and Morale 57 Chapter 5: Mutual Aid 61 Chapter 6: Transparency, Accountability, Public Communication, and Social Media 67 Conclusion 69 Works Cited 80 Appendix A: Recommendations and Findings 92 Appendix B: Research Design, Methods, and Data 99 Appendix C: Columbus Police After Action Review Team 109 Appendix D: List of Acronyms Acknowledgements The research presented in this report benefitted from a diversity of perspectives, backgrounds, disciplinary expertise, and professional experience. In particular, the lead researchers are indebted to the National Police Foundation, the primary subcontractor on this project. The National Police Foundation’s staff, notably Frank Straub and Ben Gorban, harnessed their expertise of policing across the United States and around the globe to ensure that the findings and recommendations aligned with the evolving knowledge base of policing best practice. We are grateful to the array of investigators and interviewers who volunteered their time, energy and expertise to conduct over 170 interviews in the midst of a global pandemic. Our Advisory Board also volunteered their time to guide the research and offer insights from a variety of disciplines that inform the as- sessment of protest behavior and police response. -

Featured Writer... Fafara Concludes, "These Five Souls Make This Band What It Is

3rd Quarter • 2012 They'll lay on their laurels and stick to what they've done on the next album. We're not look- ing at what anyone around us is doing. Since we're not paying attention to any of that, we were able to find unique music within ourselves. We tried to break some boundaries and stretch the genre open. We keep redefining ourselves." The musical prowess of the band members is becoming more evident beyond the metal world, as Spreitzer and Kendrick released signature ESP guitars. Boecklin has also been prominently featured in all drum magazines, namely Modern Drummer and DRUM!, as his kit work continues to turn heads. Featured Writer... Fafara concludes, "These five souls make this band what it is. It lies in the salt and pepper from everyone. What's most important is our fans get delivered the kind of music, stage show and energy that they're expecting from us. Because DevilDriver are preparing to release the of all the time and personal sacrifice, we are a band's sixth album, which is an exorcism of Beast. The pleasure is that we're all together as animalistic, primal hooks, thunderous percus- friends still. Nothing can stop DevilDriver." sion and propulsive thrashing. While many This Beast is alive and won't ever die. You have bands in the modern era are already wither- been warned… ing away by their second album and have shriveled up and died by their third, Devil- Look for DevilDriver's new album in 2013 on Driver have proven to mutate, growing stron- Napalm Records. -

Dj Drama Mixtape Mp3 Download

1 / 2 Dj Drama Mixtape Mp3 Download ... into the possibility of developing advertising- supported music download services. ... prior to the Daytona 500. continued on »p8 No More Drama Will mixtape bust hurt hip-hop? ... Highway Companion Auto makers embrace MP3 Barsuk Backed Something ... DJ Drama's Bust Leaves Future Of The high-profile police raid.. Download Latest Dj Drama 2021 Songs, Albums & Mixtapes From The Stables Of The Best Dj Drama Download Website ZAMUSIC.. MP3 downloads (160/320). Lossless ... SoundClick fee (single/album). 15% ... 0%. Upload limits. Number of tracks. Unlimited. Unlimited. Unlimited. MP3 file.. Dec 14, 2020 — Bad Boy Mixtape Vol.4- DJ S S(1996)-mf- : Free Download. Free Romantic Music MP3 Download Instrumental - Pixabay. Lil Wayne DJ Drama .... On this special episode, Mr. Thanksgiving DJ Drama leader of the Gangsta Grillz movement breaks down how he changed the mixtape game! He's dropped .. Apr 16, 2021 — DJ Drama, Jacquees – ”QueMix 4′ MP3 DOWNLOAD. DJ Drama, Jacquees – ”QueMix 4′: DJ Drama join forces tithe music sensation .... Download The Dedication Lil Wayne MP3 · Lil Wayne:Dedication 2 (Full Mixtape)... · Lil Wayne - Dedication [Dedication]... · Dedicate... · Lil Wayne Feat. DJ Drama - .... Dj Drama Songs Download- Listen to Dj Drama songs MP3 free online. Play Dj Drama hit new songs and download Dj Drama MP3 songs and music album ... best blogs for downloading music, The Best of Music For Content Creators and ... SMASH THE CLUB | DJ Blog, Music Blog, EDM Blog, Trap Blog, DJ Mp3 Pool, Remixes, Edits, ... Dec 18, 2020 · blog Mix Blog Studio: The Good Kind of Drama.. Juelz Santana. -

AUDIO + VIDEO 4/13/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to Be Taken Directly to the Sell Sheet

NEW RELEASES WEA.COM ISSUE 07 APRIL 13 + APRIL 20, 2010 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word AUDIO + VIDEO 4/13/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to be taken directly to the Sell Sheet. Click on the Artist Name in the Order Due Date Sell Sheet to be taken back to the Recap Page Street Date CD- NON 521074 ALLEN, TONY Secret Agent $18.98 4/13/10 3/24/10 CD- RAA 523695 BECK, JEFF Emotion & Commotion $18.98 4/13/10 3/24/10 CD- ATL 521144 CASTRO, JASON Jason Castro $9.94 4/13/10 3/24/10 DV- WRN 523924 CUMMINS, DAN Crazy With A Capital F (DVD) $16.95 4/13/10 3/17/10 CD- ASW 523890 GUCCI MANE Burrrprint (2) HD $13.99 4/13/10 3/24/10 CD- LAT 524047 MAGO DE OZ Gaia III - Atlantia $20.98 4/13/10 3/24/10 CD- MERCHANT, NON 522304 NATALIE Leave Your Sleep (2CD) $24.98 4/13/10 3/24/10 CD- MERCHANT, Selections From The Album NON 522301 NATALIE Leave Your Sleep $18.98 4/13/10 3/24/10 CD- LAT 524161 MIJARES Vivir Asi - Vol. II $16.98 4/13/10 3/24/10 CD- STRAIGHT NO ATL 523536 CHASER With A Twist $18.98 4/13/10 3/24/10 4/13/10 Late Additions Street Date Order Due Date CD- ERP 524163 GLORIANA Gloriana $13.99 4/13/10 3/24/10 CD- MFL 524110 GREAVER, PAUL Guitar Lullabies $11.98 4/13/10 3/24/10 Last Update: 03/03/10 ARTIST: Tony Allen TITLE: Secret Agent Label: NON/Nonesuch Config & Selection #: CD 521074 Street Date: 04/13/10 Order Due Date: 03/24/10 Compact Disc UPC: 075597981001 Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 1 SRP: $18.98 Alphabetize Under: T File Under: World For the latest up to date info on this release visit WEA.com. -

Queens Today

VolumeVol. 66, No.65, 37No. 207 MONDAY,THURSDAY, FEBRUARY JUNE 4, 10, 2020 2020 50¢ Dr. Berenecea Johnson Eanes ‘We can is the interim QUEENS president of York College. turn toward’ Photo courtesy of York College TODAY Community must unite during this FebruaryJUNE 4, 10, 2020 2020 time of turmoil QUEENS COUNCILMEMBER BOB By Berenecea Johnson Eanes, PhD Holden has called for the National Guard to Special to the Eagle be deployed to New York City, but Mayor Bill Three names are on my mind as I write de Blasio said that would be unnecessary. this with a heavy heart: Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. “WHEN OUTSIDE ARMED FORCES Three families mourning loved ones go into communities no good comes of it,” de who did not return home. They now join a Blasio said yesterday. “We have seen this for much longer list of Black individuals who decades…They have not been spending de- have been senselessly killed as we yet cades on the relationship between police and again are reminded of the seemingly ines- communities,QUEENS particularly in the intensive way capable presence of racism in its various that it has been worked on in recent years.” forms in our country. These are tragic times, but we do not THE COUNCIL WILL VOTE JUNE 9 have to be limited by these events or in on two police reform bills introduced by the ways we choose to respond to one an- Queens Councilmembers Donovan Richards, other. We must fully center our humanity will have a specific impact on Queens. -

Finding Logic in Music As with Most Parents, You’Ll Artist, and As That I Loved About Growing Up,” Do Anything for Your Kids — Any Good Par- Logic Said

D Book review An edition of the A look at heroic dogs Sunday, July 10, 2016 attractions PAGE D8 Area artists hope to create a home for glass blowing By Marcela Creps 812-331-4375 | [email protected] loomington is home to many creative opportunities, and if Abby Gitlitz gets her way, another chance to express yourself artistically may be available soon. Gitlitz is hard at work try- ing to give a permanent home to the Bloomington Creative Glass Center, a nonprofit dedicated to glass art. Despite inter- est in learning about working in glass, the center doesn’t have a glass-blowing studio or a place to teach the public about glass art. In 2009, Gitlitz moved back to Bloomington BENEDICT JONES | COURTESY PHOTO and realized there was no glass-blowing facility Glass pumpkins are sold as a fundraiser for the Blooming- in Bloomington. She wanted to fix that but wasn’t ton Creative Glass Center. sure what to do. In 2010, she hosted the first ever COURTESY PHOTO Great Glass Pumpkin Patch event — a fundraiser was that new students created glass pumpkins Erin Cerwinski is shown pulling a glass fl ower. more for herself as a struggling artist — that now that Gitlitz could sell at the annual fall event. funds the Bloomington Creative Glass Center. The pumpkin patch has found success. Each Following that event, Gitlitz found that lots of where people can learn various types of glass art fall, blown glass pumpkins are displayed on the and established artists can have a local place to people wanted not only to buy glass pumpkins but Monroe County Courthouse lawn with proceeds also to learn how to create. -

Lil Wayne, Tip “T.I.” Harris, Gucci Mane, Yo Gotti, Cardi B., YG, and A$AP Rocky Set to Perform at the BET “HIP HOP AWARDS” 2018

Lil Wayne, Tip “T.I.” Harris, Gucci Mane, Yo Gotti, Cardi B., YG, and A$AP Rocky Set to Perform at the BET “HIP HOP AWARDS” 2018 October 2, 2018 Lil Pump, Lil Baby, Lil Duval, Flipp Dinero, Ball Greezy, Gunna, and Pardison Fontaine Also Hitting the BET Stage for the First Time ------ DJ Khaled, Wale, Bun B, City Girls’ Yung Miami, and Cast of BET’s Hustle in Brooklyn to Present ------ The BET “HIP HOP AWARDS” 2018 Hosted by Audacious Comedian Deray Davis Will Honor Lil Wayne with “I Am Hip Hop” Award BET “HIP HOP AWARDS” 2018 Premieres on Tuesday, October 16, 2018 at 8PM ET/PT ----- #HipHopAwards ----- NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Oct. 2, 2018-- BET “HIP HOP AWARDS” 2018, the biggest night for hip-hop on television, is only getting bigger and better with Lil Wayneperforming fresh off the heels of the release of his highly anticipated album Tha Carter V. Other confirmed performers include hip-hop mogul and BET’s The Grand Hustle star TIPT.I. Harris, Gucci Mane, Yo Gotti, YG, and a breakout from the BET “Hip Hop Awards” highly anticipated cyphers A$AP Rocky. The first female hip-hop artist with three Hot 100 number one singles Cardi B., will be doing a special performance from LIV Nightclub at Fontainebleau. The BET “Hip Hop Awards” 2018 stage will serve as the first nationally televised performance for some of the year's hottest artists & songs in hip hop including Best New Hip-Hop Artist nominee Lil Pump, Lil Baby,Lil Duval,Flipp Dinero, Ball Greezy, Gunna, and Pardison Fontaine.