The Pleasures of Puzzle-Solving in Adventure Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Lucasarts and the Design of Successful Adventure Games

LucasArts and the Design of Successful Adventure Games: The True Secret of Monkey Island by Cameron Warren 5056794 for STS 145 Winter 2003 March 18, 2003 2 The history of computer adventure gaming is a long one, dating back to the first visits of Will Crowther to the Mammoth Caves back in the 1960s and 1970s (Jerz). How then did a wannabe pirate with a preposterous name manage to hijack the original computer game genre, starring in some of the most memorable adventures ever to grace the personal computer? Is it the yearning of game players to participate in swashbuckling adventures? The allure of life as a pirate? A craving to be on the high seas? Strangely enough, the Monkey Island series of games by LucasArts satisfies none of these desires; it manages to keep the attention of gamers through an admirable mix of humorous dialogue and inventive puzzles. The strength of this formula has allowed the Monkey Island series, along with the other varied adventure game offerings from LucasArts, to remain a viable alternative in a computer game marketplace increasingly filled with big- budget first-person shooters and real-time strategy games. Indeed, the LucasArts adventure games are the last stronghold of adventure gaming in America. What has allowed LucasArts to create games that continue to be successful in a genre that has floundered so much in recent years? The solution to this problem is found through examining the history of Monkey Island. LucasArts’ secret to success is the combination of tradition and evolution. With each successive title, Monkey Island has made significant strides in technology, while at the same time staying true to a basic gameplay formula. -

Splat the Cat: the Name of the Game Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SPLAT THE CAT: THE NAME OF THE GAME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rob Scotton | 31 pages | 17 Aug 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780062090140 | English | New York, United States Splat the Cat: The Name of the Game PDF Book Continuum Games. A "celebrity vegetable museum" just wouldn't be funny in a Disney film. Matrix Games. Customer Service. Animal Crossing. Reduced Price. If you bat an Atari joystick quickly from left to right, Pac-Man looks confused as he turns from side to side, and that's funny. This is a game. Basic Fun! But once Duke's crass style became its own archetype, Croteam brought about Sam 'Serious' Stone, who injected some much-needed sarcasm and self-doubt into Duke's braggadocio. DZT Family board games , ideal for family game nights, are designed for various ages to play side by side, encouraging your child to bond with all generations of players. The visual amount displayed in the in-game Mobility meter. The student without a partner is the 'leader'. The plot goes all H. You, as the player, are put into different sit-com scenarios that complement the game's known quantities--Homer, Lisa, Bart, Flanders, Marge, Apu, and so on. Have fun! Next, erase the target vocabulary from the board and stick up both team's pictures in a random order. Mayday Games. Both board games and puzzles have the ability to lengthen a child's attention span as they become excited to be engaged in the activity. Portal Games. Japanime Games. The visual amount displayed in the in- game Damage meter. -

Días De Tentáculos

B R U M A L Revista de Investigación sobre lo Fantástico DOI: https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/brumal.468 Research Journal on the Fantastic Vol. VI, n.º 1 (primavera/spring 2018), pp. 163-183, ISSN: 2014-7910 DÍAS DE TENTÁCULOS. HUMOR, SERIE B Y FANTASÍA CINÉFILA EN LAS AVENTURAS GRÁFICAS DE LUCASARTS MARIO-PAUL MARTÍNEZ FABRE Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche [email protected] FRAN MATEU Universidad de Alicante [email protected] Recibido: 10-01-2018 Aceptado: 02-05-2018 RESUMEN Desde mediados de los años ochenta hasta finales de la década de los noventa, las aventuras gráficas vivieron un periodo de esplendor en el mercado del videojuego. La compañía LucasArts, con su particular mezcla de humor, cinefilia y sencillez de con- trol, dibujó el molde a seguir para las demás desarrolladoras de juegos digitales. Este artículo pretende exponer, a través de dos de sus ejemplos más importantes, Maniac Mansion y su secuela, Day of the Tentacle, cuáles fueron los principales argumentos que la instituyeron, no sólo como uno de los referentes esenciales del espacio lúdico, sino también como uno de los objetos culturales más señalados de su época, al englobar y transmitir, desde su propio intertexto y su cualidad novedosa, a otros medios como la literatura, la animación, la televisión, y, primordialmente, el cine. PALABRAS CLAVE: Humor, cine, videojuegos, serie B, LucasArts. ABSTRACT From the mid-eighties to the end of the nineties, the graphic adventures experienced a period of splendor in the video game market. The company LucasArts, with its par- ticular mixture of humor, cinephilia and simplicity of control, drew the format to fol- low for other developers of digital games. -

Ben There, Dan That! / Time Gentlemen, Please!

Ben There, Dan That! / Time Gentlemen, Please! Even though Sierra and LucasArts gave up on adventure games around the turn of the century, there are still those who hold on to the belief that the genre is very much alive. But without the continuation of games like Monkey Island, Space Quest and Simon the Sorcerer, what we have are, mostly, legions of humorless entries with depressingly dry CG backgrounds, plus the occasional cartoonish adventure that tries to be funny but fails spectacularly. Former adventure creators still make some great work, of course. Tim Schaefer, of Grim Fandango, spent a long time working on Psychonauts and Brütal Legend, both of which were hilarious despite not being adventure games, while Telltale, formed with some of the other LucasArts staff, comes close to the glory days of the genre. But it‟s not quite the same. So it was more or less out of nowhere that a tiny group of Brits called Zombie Cow Studios brought out two of the funniest adventures since... well, since ever, perhaps. Ben There, Dan That! and its sequel, Time Gentlemen Please!, are both low budget hits made with Adventure Game Studio and have a graphical style most consistent with elementary school notebook doodles, but succeed tremendously because they‟re so brilliantly written. One could call it “The British version of South Park!” and that wouldn‟t entirely be wrong, but that‟s a glib summation of it. While both creations have uber low-fi visuals, subversive plotting, and more than just a bit of toilet humor, Zombie Cow‟s games replace South Park's libertarian cynicism with a self aware affection for adventure games, LucasArts in particular. -

Copyrighted Material

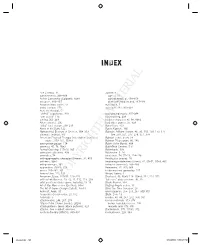

Index Ace Combat, 11 audience achievements, 368–369 age of, 29 Action Cartooning (Caldwell), 84n1 control needs of, 158–159 actuators, 166–167 pitch presentation and, 417–421 Advance Wars series, 11 Auto Race, 7 aerial combat, 270 autosave, 192, 363–364 Aero the Acrobat, 52 “ah-ha!” experience, 349 background music, 397–398 “aim assist,” 173 backtracking, 228 aiming, 263–264 badass character, 86–88, 86n2 Aliens (movie), 206 bad video games, 25, 429 “alley” level design, 218–219 Band Hero, 403 Alone in the Dark, 122 Banjo-Kazooie, 190 Alphabetical Bestiary of Choices, 304–313 Batman: Arkham Asylum, 46, 50, 110, 150, 173, 177, alternate endings, 376 184, 250, 251, 277, 278, 351, 374 American Physical Therapy Association exercises/ Batman comic book, 54 advice, 159–161, 159n3 Batman TV program, 86, 146 ammunition gauge, 174 Battle of the Bands, 404 amnesia, 47, 76, 76n9 BattleTech Centers, 5–6 Animal Crossing, 117n10, 385 Battletoads, 338 animated cutscenes, 408 Battlezone, 5, 14 animatics, 74 beat chart, 74, 77–79, 214–216 anthropomorphic characters/themes, 92, 459 Beetlejuice (movie), 18 anti-hero, 86n2 beginning/middle/end (stories), 41, 50–51, 50n9, 435 anti-power-ups, 361 behavior (enemies), 284–289 appendixes (GDD), 458 Bejeweled, 41, 350, 368 armor, 259–261, 361 bi-dimensional gameplay, 127 Army of Two, 112, 113 Bilson, Danny, 3 Arnenson, Dave, 217n13, 223–229 Bioshock, 46, 46n9, 118, 208n9, 212, 214, 372 artifi cial intelligence, 13,COPYRIGHTED 42, 71, 112, 113, 293 “bite-size” MATERIAL play sessions, 46, 79 artist positions (video game industry), 13–14 Blade Runner, 397 Art of Star Wars series (Del Rey), 84n1 Blazing Angels series, 11 The Art of Game Design (Schell), 15n14 Blinx: the Time Sweeper, 26 Ashcraft, Andy, 50 blocks/parries, 258–259, 287, 300–301 Assassin’s Creed series, 21, 172 Bluth, Don, 13 Asteroids, 5 bombs, 47–48, 247, 272, 358, 381 attack matrix, 248, 267, 279 bonus materials, 373–376 Attack of the Clones (movie), 202n6 bonus materials screen, 195 attack patterns (boss attack patterns), 323 rewards and, 373–376 attacks. -

Lisez-Moi Scummvm

Lisez-moi ScummVM Dernière mise à jour : 26/03/05 20:50 Version : 0.7.1 1 Pour plus d'information, liste de compatibilité, détails sur la donation, la dernière version, rapport de progrès et plus, veuillez visiter la page de ScummVM à : http://www.scummvm.org/ Table des matières 1) A propos :.........................................................................................................................................2 2) Nous contacter :................................................................................................................................3 2.1) Rapporter des bugs :................................................................................................................. 3 3) Jeux supportés :................................................................................................................................4 3.1) Protection contre la copie :....................................................................................................... 5 3.2) Notes sur Simon the Sorcerer 1 et 2 :....................................................................................... 5 3.3) Notes sur Broken Sword (Les chevaliers de Baphomet) :........................................................6 3.4) Notes sur Flight of the Amazon Queen :.................................................................................. 6 3.5) Problèmes connus de ScummVM 0.7.1................................................................................... 6 4) Plateformes supportées :...................................................................................................................8 -

Lucasarts-98Catalog

01-092 PRICE $39.95 PLATFORM Windows 95 CD-ROM CATEGORY Meet Manny Calavera-suave, debonair Grophic Advenlure; Single-play travel agent in the Land of the Dead. AVAILABILITY Lately some of his customers have been Now getting bilked out of the "eternal rest" promised in the color brochures. What's a working stiff to do? Plunge headlong into an engrossing film-noir adventure of corruption and deceit, sprinkled with a huge dose of wry humor and amazing 3D graphics. Once you fall for Manny's ITEM# charms, you may never stop playing. 18-013 GRIM FANDANGO STRATEGY GUIDE The official handbook of tips, tricks ORDER INFORMATION and inside moves for power-players Grim Fandango #01-092 ········· . ...... $39.95 and beginners. Grim Fandango Official Strategy Guide #18-013 .......... .........$19.95 Or 24 hours a day www.lucasarts.com i Cata log Minimum WIN.95 RAM Minimum Recommended Game Title Page# Operating System Compatible Required Processor Processor Afterlife - PC p.22 MS.DOS 6.0 Ye• 8M8 486DX2/66 486DX2/66 Afterlife - MAC p.22 Moc OS 7.1 8M8 68040 33 mhz Power PC l.i r"C:'t.~ba·i ·ciaiii<i ·~ · Pi: .. · · .. .. .... j;:2s ·· .............. · "i:iS:oofaii .. No 64ok ~~~(1 : ~ ..... ' .. :::: :::: :~~:~ :::: .. Balii'I~~--~ ' (:°t\~mpion~ ·:.: PSx p. 13 ·· · · · · · · ..... · .. ·. ··. ·· · · ·. ·· .. ·· · ·. .................. .. 28i;/16' ............. 28i;/1'6 Ci~s~·i~ · Adv·~~t~;~~ · :: · pc ·· .......... · ··p-.24 · MS.COS 3.0 No 640k Dari<. F;;;c;;;· ~ PC: ·· · · · · · .. ·· · · · · · · · · .. ·· · · .;.i1 MS.DOS 5.0 Ye• 8MB .. ·:ia6ox/:i3 "is6ox/:i3 · Dark Farces - MAC p.21 Moc0571 8MB 68040 68040 33 mhz Dark Forces - PSX p.13 ... .. ................ Day·.; f ih&.r& .~ia~·1 ;; ·::·lie· ·p:24" MS.DOS 5.0 No 4MB 286 386/33 Day of the Tentacle - MAC p.24 Moc OS 7.1 8MB 68040 68040 . -

Tony Dorie March 22, 2001 STS145: History of Computer Game Design Henry Lowood

Tony Dorie March 22, 2001 STS145: History of Computer Game Design Henry Lowood LucasArts and Lucasfilm: A Good Deal for All Involved Introduction: George Lucas is the king over an empire. Over the last thirty-five plus years he has created some of the most recognizable characters of our time. These characters are so ubiquitous in America that they are almost burned into our collective unconscious; they are the archetypes of the modern era. The mention of Star Wars or Indiana Jones sets off the imagination, drawing people into the worlds Lucas has created. The music from both series of movies is immediately recognizable as are the names Luke Skywalker, Yoda, Princess Leia, Darth Vader, Indiana Jones and Obi-Wan Kenobi. While the movies made around these characters welcomed them to the world, their influence is also attributed to their extremely adept promotion. Additionally, most of the money made from these characters comes not from their movies but rather from their merchandise. The Star Wars series has spawned countless spin-offs, all of which serve to increase the public's awareness of them. There have been books, toys, comic books, clothing, radio shows, a Disneyland ride, food items, cartoons, novelties and over twenty-five computer and video games. The Indiana Jones series has been no slouch either, giving rise to toys, books, a television show, another Disneyland ride, comic books and its own set of computer and video games. It is easy to see that George Lucas is a very shrewd businessman. When the original Star Wars movie was made, he retained the rights to any merchandise and he has used those rights brilliantly. -

Day of the Tentacle Remastered by Double Fine Productions, Inc., Get Itunes Now

Présentation Musique Vidéo Classements iTunes is the world's easiest way to organize and add to your digital media collection. We are unable to find iTunes on your computer. To buy and download Day of the Tentacle Remastered by Double Fine Productions, Inc., get iTunes now. Do you already have iTunes? Click I Have iTunes to open it now. Day of the Tentacle Remastered Game Center By Double Fine Productions, Inc. View More by This Developer Open iTunes to buy and download apps. Description Dr. Fred’s mutated purple tentacle is about to take over the world, and only you can stop him! Originally released by LucasArts in 1993 as a sequel to Ron Gilbert’s ground breaking Maniac Mansion, Day of the Tentacle is a mind-bending, time travel, cartoon puzzle adventure game in which three unlikely friends work together to prevent an evil mDouutabteled Fpiunrep lPer toednutacctlieo nfrso,m In tca.k iWnge bo vSeirt ethe wDoarlyd !of the Tentacle Remastered Support ...More Now, over twenty years later, Day of the Tentacle is back in a remastered edition that features all new hand-drawn, high Srescorluetioenn asrtwhoorkt,s with remastered audio, music and sound effects (which the original 90s marketing blurb descriibPehdo naes ‘z aiPnya!d’). Players are able to switch back and forth between classic and remastered modes, and mix and match audio, graphics and user interface to their heart’s desire. We’ve also included a concept art browser, and recorded a commentary track with the game’s This app is designed for both original creators Tim Schafer, Dave Grossman, Larry Ahern, Peter Chan, Peter McConnell and Clint Bajakian. -

The Trouble Began When Purple Tentacle Drank That Pesky

.About M.a.Zlia.c: M.a.Zl..sio%1® 4: 'Day of the. 're.Zltac:le.·~ he trouble began when Purple Tentacle drank that pesky toxic waste. Once evil but harmlessly slow-witted, he T became an evil super-genius, bent on WORLD DOMINA TION! His creator, fidgety mad scientist Doctor Fred Edison, realised the threat to all humanity and captured Purple Tentacle, along with his good-natured brother Green Tentacle, and plans to have them put to sleep. Bernard, the computer geek with a heart of gold, must free his old friend Green Tentacle! But at what cost? This time, he may be in over his head. His roomates Hoagie, a heavy metal roadie, and Laverne, a slightly twitchy medical student, are along to help, unaware of what lays in store. Time travel, tax evasion, talking horses, beauty pageants, skunk-tossing, and even a little clown-fu an adventure spanning four-hundred years- all crammed into one fateful night. They were relaxing at home when the hamster knocked on the door. .. Stopping this menace is up to you! You direct the actions of all three kids, cavorting though time in a frantic quest to return to yes terday and stop this Tyrannical Tentacle before he can even get started on his promise to make the world bow down to ... The Day of the Tentacle! If this is your first computer adventure game, be prepared for an entertaining challenge. Be patient, even if it takes a while to figure out some of the puzzles. Ify ou get stuck, you might need to solve another puzzle first or find and use a new object. -

Grim Fandango, an Adventure Game by Lucasarts

How Lua Brought the Dead to Life A historic footnote and dangerous precedent Bret Mogilefsky [email protected] Don't sue me! ● This is a presentation about how Lua was used in Grim Fandango, an adventure game by LucasArts ● I don't work for LucasArts anymore – However, all materials are used with their permission (official text to follow) ● I do work for Sony Computer Entertainment America – However, I am not speaking in any official capacity – I have to go back to work later... :( What’s an adventure game? ● In this case: – Characters (3D models and 2D sprites) – Environments (pre-rendered backgrounds with z-channel) – Story (text display engine, cutscenes) – Puzzles (creative writing and design) ● Includes 8000 lines of dialog! It looks like this Why use a scripting language? ● Glue! – 95% of animations and cutscenes are custom – Scripting language is key to reducing weight – Clean separation of engine from content – Example: ● actor guybrush walk-to banana-tree wait-for-actor actor guybrush say-line “Mmm, bananas...” actor guybrush face-camera actor guybrush say-line “Wish I had a banana-picker” What existed (I) ● SCUMM: Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion – SCUMM is really just the language – SPUTM (interpreter aka game engine) – FLEM, BYLE, etc. for creating assets ● Proven technology – Used in dozens of shipping titles – Multi-platform What existed (II) ● Huge pedigree of beloved games – Maniac Mansion, Secret of Monkey Island I & II, Sam and Max, Day of the Tentacle, Full Throttle... ● Talented designers and artists What