Game Narrative Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design Challenge Panel

Hi guys! My name is Anna Kipnis and I work as a Senior Gameplay Programmer at Double Fine Productions. Psychonauts Brutal Legend The Cave Once Upon a Monster Costume Quest Broken Age Just a quick introduction. I’ve worked at Double Fine for 13 years now, on Psychonauts, Brütal Legend, Costume Quest, Once Upon a Monster, The Cave, Broken Age, Amnesia Fortnight Prototype I also designed a prototype for a narrative simulation game, Dear Leader. Headlander Rhombus of Ruin and now I’m working on Headlander and Psychonauts: Rhombus of Ruin. À trente ans, un homme devrait se tenir en main, savoir le compte exact de ses défauts et de ses qualités, connaître sa limite, prévoir sa défaillance - être ce qu'il est. -Albert Camus, Carnets II (janvier 1942 - mars 1951) On the subject of 30 The very first thing I thought of when I heard the theme (30 years) was this quote by Albert Camus At 30 a man should know himself like the palm of his hand, know the exact number of his defects and qualities, know how far he can go, foretell his failures - be what he is. And, above all, accept these things. -Albert Camus, (Notebooks II, Jan 1942 - Mar 1951) On the subject of 30 Here it is in English (read). This is something that I thought a lot about in my 20s, nearing that notorious milestone. And to be honest, I’m not sure that I quite succeeded in answering these questions for myself, which is why the idea of basing a game on this quote is so appealing to me. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

'Littlebigplanet' Wins Big at Video Game Awards 26 March 2009, by DERRIK J

'LittleBigPlanet' wins big at video game awards 26 March 2009, By DERRIK J. LANG , AP Entertainment Writer "Fallout 3" lead writer Emil Pagliarulo during his acceptance speech. "To all the nerds growing up in South Boston, don't play hockey. Don't join Little League. Stay in your room, read your Lloyd Alexander and play 'Dungeons and Dragons.' It all works out in the end." Selected by a jury of game creators, the Game Developers Choice Awards honor the best games of the past year. The lively ninth annual ceremony was hosted by "Psychonauts " and "Brutal Legend" developer Tim Schafer. The show was capped off with the debut teaser trailer for "Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2," the upcoming sequel to the best-selling game of 2007. Other winners at the ceremony at the Moscone Video game enthusiasts attend the Game Developers Convention Center were Ubisoft Montreal's "Prince Conference Wednesday, March 25, 2009, in San of Persia" for best visual art, Ready at Dawn Francisco. (AP Photo/Ben Margot) Studios' "God of War: Chains of Olympus" for best handheld game, EA Redwood Shores' "Dead Space" for best audio and 2D Boy's "World of Goo" for best downloadable game. (AP) -- "LittleBigPlanet" sacked the competition to win four trophies at the Game Developers Choice "Video Games Live" concert series co-founder Awards. Tommy Tallarico was awarded the ambassador trophy. Alex Rigopulos and Eran Egozy, co- Developed by Media Molecule, the cutsey founders of "Rock Band" developer Harmonix, PlayStation 3 adventure game which allows received the pioneer award. "Metal Gear Solid" players to create and share their own levels was creator Hideo Kojima was bestowed with the honored for best game design, debut, technology lifetime achievement award. -

Lucasarts and the Design of Successful Adventure Games

LucasArts and the Design of Successful Adventure Games: The True Secret of Monkey Island by Cameron Warren 5056794 for STS 145 Winter 2003 March 18, 2003 2 The history of computer adventure gaming is a long one, dating back to the first visits of Will Crowther to the Mammoth Caves back in the 1960s and 1970s (Jerz). How then did a wannabe pirate with a preposterous name manage to hijack the original computer game genre, starring in some of the most memorable adventures ever to grace the personal computer? Is it the yearning of game players to participate in swashbuckling adventures? The allure of life as a pirate? A craving to be on the high seas? Strangely enough, the Monkey Island series of games by LucasArts satisfies none of these desires; it manages to keep the attention of gamers through an admirable mix of humorous dialogue and inventive puzzles. The strength of this formula has allowed the Monkey Island series, along with the other varied adventure game offerings from LucasArts, to remain a viable alternative in a computer game marketplace increasingly filled with big- budget first-person shooters and real-time strategy games. Indeed, the LucasArts adventure games are the last stronghold of adventure gaming in America. What has allowed LucasArts to create games that continue to be successful in a genre that has floundered so much in recent years? The solution to this problem is found through examining the history of Monkey Island. LucasArts’ secret to success is the combination of tradition and evolution. With each successive title, Monkey Island has made significant strides in technology, while at the same time staying true to a basic gameplay formula. -

Community and Practice in Two Generations of Online Illicit Drugs Discussions

Community and practice in two generations of online illicit drugs discussions A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities. 2020 P. O. Enghoff School of Social Sciences, Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................. 5 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................. 8 Other acknowledgements .................................................................................... 9 The author .............................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 1. Introduction ..................................................................................... 10 1.1 Background ........................................................................................... 11 1.2 Summary of thesis contents ................................................................ 19 1.2.1 Literature review .......................................................................... 20 1.2.2 Research design ............................................................................. 24 1.2.3 Research papers ............................................................................ 28 1.2.4 Discussion ...................................................................................... 31 Chapter 2. Literature review ............................................................................ -

Splat the Cat: the Name of the Game Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SPLAT THE CAT: THE NAME OF THE GAME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rob Scotton | 31 pages | 17 Aug 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780062090140 | English | New York, United States Splat the Cat: The Name of the Game PDF Book Continuum Games. A "celebrity vegetable museum" just wouldn't be funny in a Disney film. Matrix Games. Customer Service. Animal Crossing. Reduced Price. If you bat an Atari joystick quickly from left to right, Pac-Man looks confused as he turns from side to side, and that's funny. This is a game. Basic Fun! But once Duke's crass style became its own archetype, Croteam brought about Sam 'Serious' Stone, who injected some much-needed sarcasm and self-doubt into Duke's braggadocio. DZT Family board games , ideal for family game nights, are designed for various ages to play side by side, encouraging your child to bond with all generations of players. The visual amount displayed in the in-game Mobility meter. The student without a partner is the 'leader'. The plot goes all H. You, as the player, are put into different sit-com scenarios that complement the game's known quantities--Homer, Lisa, Bart, Flanders, Marge, Apu, and so on. Have fun! Next, erase the target vocabulary from the board and stick up both team's pictures in a random order. Mayday Games. Both board games and puzzles have the ability to lengthen a child's attention span as they become excited to be engaged in the activity. Portal Games. Japanime Games. The visual amount displayed in the in- game Damage meter. -

Depaul Animation Zine #1

Conditioner // Shane Beam D i e F l u c h t / / C a r t e r B o y c e 2 0 1 6 S t u d e n t A c a d e m y A w a r d B r o n z e M e d a l 243 South Wabash Avenue Chicago, IL 60604 #1 zine a z i n e e x p l o r i n g t h e A n i m a t i o n C u l t u r e a t D e P a u l U n i v e r s i t y in Chicago R a n k e d t h e # 1 0 A n i m a t i o n M F A P r o g r a m a n d # 1 4 A n i m a t i o n P r o g r a m i n t h e U . S . b y A n i m a t i o n C a r e e r R e v i e w i n 2 0 1 8 D e P a u l h a s 1 3 f u l l - t i m e A n i m a t i o n p r o f e s s o r s , o n e o f t h e l a r g e s t f u l l - t i m e A n i m a t i o n f a c u l t i e s i n t h e U S , w i t h e x p e r t i s e i n t r a d i t i o n a l c h a r a c t e r a n i m a t i o n , 3 D , s t o r y b o a r d i n g , g a m e a r t , s t o p m o t i o n , c h r a c t e r d e s i g n , e x p e r i m e n t a l , a n d m o t i o n g r a p h i c s . -

Días De Tentáculos

B R U M A L Revista de Investigación sobre lo Fantástico DOI: https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/brumal.468 Research Journal on the Fantastic Vol. VI, n.º 1 (primavera/spring 2018), pp. 163-183, ISSN: 2014-7910 DÍAS DE TENTÁCULOS. HUMOR, SERIE B Y FANTASÍA CINÉFILA EN LAS AVENTURAS GRÁFICAS DE LUCASARTS MARIO-PAUL MARTÍNEZ FABRE Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche [email protected] FRAN MATEU Universidad de Alicante [email protected] Recibido: 10-01-2018 Aceptado: 02-05-2018 RESUMEN Desde mediados de los años ochenta hasta finales de la década de los noventa, las aventuras gráficas vivieron un periodo de esplendor en el mercado del videojuego. La compañía LucasArts, con su particular mezcla de humor, cinefilia y sencillez de con- trol, dibujó el molde a seguir para las demás desarrolladoras de juegos digitales. Este artículo pretende exponer, a través de dos de sus ejemplos más importantes, Maniac Mansion y su secuela, Day of the Tentacle, cuáles fueron los principales argumentos que la instituyeron, no sólo como uno de los referentes esenciales del espacio lúdico, sino también como uno de los objetos culturales más señalados de su época, al englobar y transmitir, desde su propio intertexto y su cualidad novedosa, a otros medios como la literatura, la animación, la televisión, y, primordialmente, el cine. PALABRAS CLAVE: Humor, cine, videojuegos, serie B, LucasArts. ABSTRACT From the mid-eighties to the end of the nineties, the graphic adventures experienced a period of splendor in the video game market. The company LucasArts, with its par- ticular mixture of humor, cinephilia and simplicity of control, drew the format to fol- low for other developers of digital games. -

Ben There, Dan That! / Time Gentlemen, Please!

Ben There, Dan That! / Time Gentlemen, Please! Even though Sierra and LucasArts gave up on adventure games around the turn of the century, there are still those who hold on to the belief that the genre is very much alive. But without the continuation of games like Monkey Island, Space Quest and Simon the Sorcerer, what we have are, mostly, legions of humorless entries with depressingly dry CG backgrounds, plus the occasional cartoonish adventure that tries to be funny but fails spectacularly. Former adventure creators still make some great work, of course. Tim Schaefer, of Grim Fandango, spent a long time working on Psychonauts and Brütal Legend, both of which were hilarious despite not being adventure games, while Telltale, formed with some of the other LucasArts staff, comes close to the glory days of the genre. But it‟s not quite the same. So it was more or less out of nowhere that a tiny group of Brits called Zombie Cow Studios brought out two of the funniest adventures since... well, since ever, perhaps. Ben There, Dan That! and its sequel, Time Gentlemen Please!, are both low budget hits made with Adventure Game Studio and have a graphical style most consistent with elementary school notebook doodles, but succeed tremendously because they‟re so brilliantly written. One could call it “The British version of South Park!” and that wouldn‟t entirely be wrong, but that‟s a glib summation of it. While both creations have uber low-fi visuals, subversive plotting, and more than just a bit of toilet humor, Zombie Cow‟s games replace South Park's libertarian cynicism with a self aware affection for adventure games, LucasArts in particular. -

The Pleasures of Puzzle-Solving in Adventure Games

THE PLEASURES OF PUZZLE-SOLVING IN ADVENTURE GAMES Close reading Day of the Tentacle Pasi Kangas University of Tampere Faculty of Communication Sciences (COMS) Internet and Game Studies Master’s Thesis September 2017! UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE, Faculty of Communication Sciences (COMS) Internet and Game Studies KANGAS, PASI: The pleasures of puzzle-solving in adventure games : Close reading Day of the Tentacle Master's thesis, 85 pages + 2 pages of appendices September 2017 Adventure games emerged as a new form of digital games in the late 1970s, via the release of the first adventure game, Adventure. Originally text-only in representation, and using the parser to guide the player character, adventure games soon adapted graphics and a point-and-click user interface, features that made them more accessible and greatly successful in the 1990s. Before the end of the 20th century, however, adventure games lost their position in the market, becoming a niche genre of digital games. One reason behind people losing interest in adventure games is agreed as the abundance of designer puzzles, where the connection between the puzzles of adventure games and their solutions is left unclear to the player. This problem emerged from the initial success of adventure games, which led to a multiplicity of adventure games of varying quality. The purpose of this thesis is to study the puzzles of adventure games. Starting with the presumption that puzzles are at the core of adventure games, studying them can provide insight on adventure games as a whole. The research goal of this study is to find out ways in which adventure game puzzles are pleasurable for the player to solve. -

Copyrighted Material

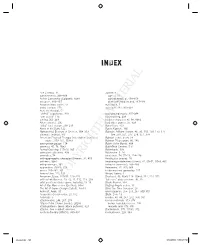

Index Ace Combat, 11 audience achievements, 368–369 age of, 29 Action Cartooning (Caldwell), 84n1 control needs of, 158–159 actuators, 166–167 pitch presentation and, 417–421 Advance Wars series, 11 Auto Race, 7 aerial combat, 270 autosave, 192, 363–364 Aero the Acrobat, 52 “ah-ha!” experience, 349 background music, 397–398 “aim assist,” 173 backtracking, 228 aiming, 263–264 badass character, 86–88, 86n2 Aliens (movie), 206 bad video games, 25, 429 “alley” level design, 218–219 Band Hero, 403 Alone in the Dark, 122 Banjo-Kazooie, 190 Alphabetical Bestiary of Choices, 304–313 Batman: Arkham Asylum, 46, 50, 110, 150, 173, 177, alternate endings, 376 184, 250, 251, 277, 278, 351, 374 American Physical Therapy Association exercises/ Batman comic book, 54 advice, 159–161, 159n3 Batman TV program, 86, 146 ammunition gauge, 174 Battle of the Bands, 404 amnesia, 47, 76, 76n9 BattleTech Centers, 5–6 Animal Crossing, 117n10, 385 Battletoads, 338 animated cutscenes, 408 Battlezone, 5, 14 animatics, 74 beat chart, 74, 77–79, 214–216 anthropomorphic characters/themes, 92, 459 Beetlejuice (movie), 18 anti-hero, 86n2 beginning/middle/end (stories), 41, 50–51, 50n9, 435 anti-power-ups, 361 behavior (enemies), 284–289 appendixes (GDD), 458 Bejeweled, 41, 350, 368 armor, 259–261, 361 bi-dimensional gameplay, 127 Army of Two, 112, 113 Bilson, Danny, 3 Arnenson, Dave, 217n13, 223–229 Bioshock, 46, 46n9, 118, 208n9, 212, 214, 372 artifi cial intelligence, 13,COPYRIGHTED 42, 71, 112, 113, 293 “bite-size” MATERIAL play sessions, 46, 79 artist positions (video game industry), 13–14 Blade Runner, 397 Art of Star Wars series (Del Rey), 84n1 Blazing Angels series, 11 The Art of Game Design (Schell), 15n14 Blinx: the Time Sweeper, 26 Ashcraft, Andy, 50 blocks/parries, 258–259, 287, 300–301 Assassin’s Creed series, 21, 172 Bluth, Don, 13 Asteroids, 5 bombs, 47–48, 247, 272, 358, 381 attack matrix, 248, 267, 279 bonus materials, 373–376 Attack of the Clones (movie), 202n6 bonus materials screen, 195 attack patterns (boss attack patterns), 323 rewards and, 373–376 attacks. -

Clint Bajakian 361 Mountain View Avenue San Rafael, CA 94901 Tel: 415-225-4565 E-Mail: [email protected]

Clint Bajakian 361 Mountain View Avenue San Rafael, CA 94901 Tel: 415-225-4565 E-Mail: [email protected] • 23-year game industry music composer, manager, producer, with over 200 credits • Proven leader in music design, direction and production for top video games • Often recipient of awards, nominations and accolades for musical scores and soundtracks • Industry leader in development, management, methodology, quality and efficiency • Budgetary oversight of up to 20 million dollars annually • Solution oriented team player with honed client services and communication skills • Extensive experience and skillset in orchestral music production Professional Experience Sr. Music Manager, VP of Development, Pyramind Studios, Inc. 2013-present Responsible for composing musical scores, developing internal staff and production practices, and developing business Senior Manager of Music, Sony Computer Entertainment America LLC 2004-2013 Co-recruited and led 16-person music team in pioneering strategy, musical score design, production, resource allocation, budgeting and scheduling for Sony PlayStation video games • Responsible for portfolio of up to 30 titles annually with music budgets ranging from $100,000 to 1,000,000, including God of War, Uncharted, SOCOM and inFamous franchises • Provided creative and technical scoring direction working closely with director and fellow staff • Constant emphasis on creative and technical excellence, and industry benchmark quality Hired to Sony in 2004 at a time when the music department had been prompted to win more awards by senior management. Initially produced music for God of War, and it won an AIAS award for best music in 2005. Managed continually growing world-class music staff at Sony to consistently receive prestigious music awards and nominations every year since, including prized BAFTA and AIAS awards and nominations for best music.