Cryptography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 3 – Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Chapter 3 –Block Ciphers and the Data Cryptography and Network Encryption Standard Security All the afternoon Mungo had been working on Stern's Chapter 3 code, principally with the aid of the latest messages which he had copied down at the Nevin Square drop. Stern was very confident. He must be well aware London Central knew about that drop. It was obvious Fifth Edition that they didn't care how often Mungo read their messages, so confident were they in the by William Stallings impenetrability of the code. —Talking to Strange Men, Ruth Rendell Lecture slides by Lawrie Brown Modern Block Ciphers Block vs Stream Ciphers now look at modern block ciphers • block ciphers process messages in blocks, each one of the most widely used types of of which is then en/decrypted cryptographic algorithms • like a substitution on very big characters provide secrecy /hii/authentication services – 64‐bits or more focus on DES (Data Encryption Standard) • stream ciphers process messages a bit or byte at a time when en/decrypting to illustrate block cipher design principles • many current ciphers are block ciphers – better analysed – broader range of applications Block vs Stream Ciphers Block Cipher Principles • most symmetric block ciphers are based on a Feistel Cipher Structure • needed since must be able to decrypt ciphertext to recover messages efficiently • bloc k cihiphers lklook like an extremely large substitution • would need table of 264 entries for a 64‐bit block • instead create from smaller building blocks • using idea of a product cipher 1 Claude -

Chapter 3 – Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Symmetric Cryptography Chapter 6 Block vs Stream Ciphers • Block ciphers process messages into blocks, each of which is then en/decrypted – Like a substitution on very big characters • 64-bits or more • Stream ciphers process messages a bit or byte at a time when en/decrypting – Many current ciphers are block ciphers • Better analyzed. • Broader range of applications. Block vs Stream Ciphers Block Cipher Principles • Block ciphers look like an extremely large substitution • Would need table of 264 entries for a 64-bit block • Arbitrary reversible substitution cipher for a large block size is not practical – 64-bit general substitution block cipher, key size 264! • Most symmetric block ciphers are based on a Feistel Cipher Structure • Needed since must be able to decrypt ciphertext to recover messages efficiently Ideal Block Cipher Substitution-Permutation Ciphers • in 1949 Shannon introduced idea of substitution- permutation (S-P) networks – modern substitution-transposition product cipher • These form the basis of modern block ciphers • S-P networks are based on the two primitive cryptographic operations we have seen before: – substitution (S-box) – permutation (P-box) (transposition) • Provide confusion and diffusion of message Diffusion and Confusion • Introduced by Claude Shannon to thwart cryptanalysis based on statistical analysis – Assume the attacker has some knowledge of the statistical characteristics of the plaintext • Cipher needs to completely obscure statistical properties of original message • A one-time pad does this Diffusion -

Cryptanalysis of a Reduced Version of the Block Cipher E2

Cryptanalysis of a Reduced Version of the Block Cipher E2 Mitsuru Matsui and Toshio Tokita Information Technology R&D Center Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5-1-1, Ofuna, Kamakura, Kanagawa, 247, Japan [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. This paper deals with truncated differential cryptanalysis of the 128-bit block cipher E2, which is an AES candidate designed and submitted by NTT. Our analysis is based on byte characteristics, where a difference of two bytes is simply encoded into one bit information “0” (the same) or “1” (not the same). Since E2 is a strongly byte-oriented algorithm, this bytewise treatment of characteristics greatly simplifies a description of its probabilistic behavior and noticeably enables us an analysis independent of the structure of its (unique) lookup table. As a result, we show a non-trivial seven round byte characteristic, which leads to a possible attack of E2 reduced to eight rounds without IT and FT by a chosen plaintext scenario. We also show that by a minor modification of the byte order of output of the round function — which does not reduce the complexity of the algorithm nor violates its design criteria at all —, a non-trivial nine round byte characteristic can be established, which results in a possible attack of the modified E2 reduced to ten rounds without IT and FT, and reduced to nine rounds with IT and FT. Our analysis does not have a serious impact on the full E2, since it has twelve rounds with IT and FT; however, our results show that the security level of the modified version against differential cryptanalysis is lower than the designers’ estimation. -

Cryptographic Sponge Functions

Cryptographic sponge functions Guido B1 Joan D1 Michaël P2 Gilles V A1 http://sponge.noekeon.org/ Version 0.1 1STMicroelectronics January 14, 2011 2NXP Semiconductors Cryptographic sponge functions 2 / 93 Contents 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Roots .......................................... 7 1.2 The sponge construction ............................... 8 1.3 Sponge as a reference of security claims ...................... 8 1.4 Sponge as a design tool ................................ 9 1.5 Sponge as a versatile cryptographic primitive ................... 9 1.6 Structure of this document .............................. 10 2 Definitions 11 2.1 Conventions and notation .............................. 11 2.1.1 Bitstrings .................................... 11 2.1.2 Padding rules ................................. 11 2.1.3 Random oracles, transformations and permutations ........... 12 2.2 The sponge construction ............................... 12 2.3 The duplex construction ............................... 13 2.4 Auxiliary functions .................................. 15 2.4.1 The absorbing function and path ...................... 15 2.4.2 The squeezing function ........................... 16 2.5 Primary aacks on a sponge function ........................ 16 3 Sponge applications 19 3.1 Basic techniques .................................... 19 3.1.1 Domain separation .............................. 19 3.1.2 Keying ..................................... 20 3.1.3 State precomputation ............................ 20 3.2 Modes of use of sponge functions ......................... -

Historical Ciphers • A

ECE 646 - Lecture 6 Required Reading • W. Stallings, Cryptography and Network Security, Chapter 2, Classical Encryption Techniques Historical Ciphers • A. Menezes et al., Handbook of Applied Cryptography, Chapter 7.3 Classical ciphers and historical development Why (not) to study historical ciphers? Secret Writing AGAINST FOR Steganography Cryptography (hidden messages) (encrypted messages) Not similar to Basic components became modern ciphers a part of modern ciphers Under special circumstances modern ciphers can be Substitution Transposition Long abandoned Ciphers reduced to historical ciphers Transformations (change the order Influence on world events of letters) Codes Substitution The only ciphers you Ciphers can break! (replace words) (replace letters) Selected world events affected by cryptology Mary, Queen of Scots 1586 - trial of Mary Queen of Scots - substitution cipher • Scottish Queen, a cousin of Elisabeth I of England • Forced to flee Scotland by uprising against 1917 - Zimmermann telegram, America enters World War I her and her husband • Treated as a candidate to the throne of England by many British Catholics unhappy about 1939-1945 Battle of England, Battle of Atlantic, D-day - a reign of Elisabeth I, a Protestant ENIGMA machine cipher • Imprisoned by Elisabeth for 19 years • Involved in several plots to assassinate Elisabeth 1944 – world’s first computer, Colossus - • Put on trial for treason by a court of about German Lorenz machine cipher 40 noblemen, including Catholics, after being implicated in the Babington Plot by her own 1950s – operation Venona – breaking ciphers of soviet spies letters sent from prison to her co-conspirators stealing secrets of the U.S. atomic bomb in the encrypted form – one-time pad 1 Mary, Queen of Scots – cont. -

The SKINNY Family of Block Ciphers and Its Low-Latency Variant MANTIS (Full Version)

The SKINNY Family of Block Ciphers and its Low-Latency Variant MANTIS (Full Version) Christof Beierle1, J´er´emy Jean2, Stefan K¨olbl3, Gregor Leander1, Amir Moradi1, Thomas Peyrin2, Yu Sasaki4, Pascal Sasdrich1, and Siang Meng Sim2 1 Horst G¨ortzInstitute for IT Security, Ruhr-Universit¨atBochum, Germany [email protected] 2 School of Physical and Mathematical Sciences Nanyang Technological University, Singapore [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 3 DTU Compute, Technical University of Denmark, Denmark [email protected] 4 NTT Secure Platform Laboratories, Japan [email protected] Abstract. We present a new tweakable block cipher family SKINNY, whose goal is to compete with NSA recent design SIMON in terms of hardware/software perfor- mances, while proving in addition much stronger security guarantees with regards to differential/linear attacks. In particular, unlike SIMON, we are able to provide strong bounds for all versions, and not only in the single-key model, but also in the related-key or related-tweak model. SKINNY has flexible block/key/tweak sizes and can also benefit from very efficient threshold implementations for side-channel protection. Regarding performances, it outperforms all known ciphers for ASIC round-based implementations, while still reaching an extremely small area for serial implementations and a very good efficiency for software and micro-controllers im- plementations (SKINNY has the smallest total number of AND/OR/XOR gates used for encryption process). Secondly, we present MANTIS, a dedicated variant of SKINNY for low-latency imple- mentations, that constitutes a very efficient solution to the problem of designing a tweakable block cipher for memory encryption. -

The Impetus to Creativity in Technology

The Impetus to Creativity in Technology Alan G. Konheim Professor Emeritus Department of Computer Science University of California Santa Barbara, California 93106 [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: We describe the technical developments ensuing from two well-known publications in the 20th century containing significant and seminal results, a paper by Claude Shannon in 1948 and a patent by Horst Feistel in 1971. Near the beginning, Shannon’s paper sets the tone with the statement ``the fundamental problem of communication is that of reproducing at one point either exactly or approximately a message selected *sent+ at another point.‛ Shannon’s Coding Theorem established the relationship between the probability of error and rate measuring the transmission efficiency. Shannon proved the existence of codes achieving optimal performance, but it required forty-five years to exhibit an actual code achieving it. These Shannon optimal-efficient codes are responsible for a wide range of communication technology we enjoy today, from GPS, to the NASA rovers Spirit and Opportunity on Mars, and lastly to worldwide communication over the Internet. The US Patent #3798539A filed by the IBM Corporation in1971 described Horst Feistel’s Block Cipher Cryptographic System, a new paradigm for encryption systems. It was largely a departure from the current technology based on shift-register stream encryption for voice and the many of the electro-mechanical cipher machines introduced nearly fifty years before. Horst’s vision directed to its application to secure the privacy of computer files. Invented at a propitious moment in time and implemented by IBM in automated teller machines for the Lloyds Bank Cashpoint System. -

The QARMA Block Cipher Family

The QARMA Block Cipher Family Almost MDS Matrices Over Rings With Zero Divisors, Nearly Symmetric Even-Mansour Constructions With Non-Involutory Central Rounds, and Search Heuristics for Low-Latency S-Boxes Roberto Avanzi Qualcomm Product Security, Munich, Germany [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. This paper introduces QARMA, a new family of lightweight tweakable block ciphers targeted at applications such as memory encryption, the generation of very short tags for hardware-assisted prevention of software exploitation, and the con- struction of keyed hash functions. QARMA is inspired by reflection ciphers such as PRINCE, to which it adds a tweaking input, and MANTIS. However, QARMA differs from previous reflector constructions in that it is a three-round Even-Mansour scheme instead of a FX-construction, and its middle permutation is non-involutory and keyed. We introduce and analyse a family of Almost MDS matrices defined over a ring with zero divisors that allows us to encode rotations in its operation while maintaining the minimal latency associated to {0, 1}-matrices. The purpose of all these design choices is to harden the cipher against various classes of attacks. We also describe new S-Box search heuristics aimed at minimising the critical path. QARMA exists in 64- and 128-bit block sizes, where block and tweak size are equal, and keys are twice as long as the blocks. We argue that QARMA provides sufficient security margins within the constraints de- termined by the mentioned applications, while still achieving best-in-class latency. Implementation results on a state-of-the art manufacturing process are reported. -

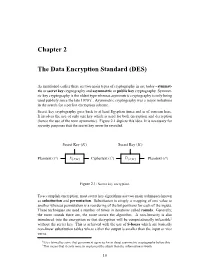

Chapter 2 the Data Encryption Standard (DES)

Chapter 2 The Data Encryption Standard (DES) As mentioned earlier there are two main types of cryptography in use today - symmet- ric or secret key cryptography and asymmetric or public key cryptography. Symmet- ric key cryptography is the oldest type whereas asymmetric cryptography is only being used publicly since the late 1970’s1. Asymmetric cryptography was a major milestone in the search for a perfect encryption scheme. Secret key cryptography goes back to at least Egyptian times and is of concern here. It involves the use of only one key which is used for both encryption and decryption (hence the use of the term symmetric). Figure 2.1 depicts this idea. It is necessary for security purposes that the secret key never be revealed. Secret Key (K) Secret Key (K) ? ? - - - - Plaintext (P ) E{P,K} Ciphertext (C) D{C,K} Plaintext (P ) Figure 2.1: Secret key encryption. To accomplish encryption, most secret key algorithms use two main techniques known as substitution and permutation. Substitution is simply a mapping of one value to another whereas permutation is a reordering of the bit positions for each of the inputs. These techniques are used a number of times in iterations called rounds. Generally, the more rounds there are, the more secure the algorithm. A non-linearity is also introduced into the encryption so that decryption will be computationally infeasible2 without the secret key. This is achieved with the use of S-boxes which are basically non-linear substitution tables where either the output is smaller than the input or vice versa. 1It is claimed by some that government agencies knew about asymmetric cryptography before this. -

On Recent Attacks Against Cryptographic Hash Functions

On recent attacks against Cryptographic Hash Functions Martin Ekerå & Henrik Ygge 1 Outline ‣ First part ‣ Preliminaries ‣ Which cryptographic hash functions exist? ‣ What degree of security do they offer? ‣ An introduction to Wang’s attack ‣ Second part ‣ Wang’s attack applied to MD5 ‣ Demo 2 Part I 3 Operators Symbol Meaning x ⊞ y Addition modulo 2n x ⊟ y Subtraction modulo 2n x ⊕ y Exclusive OR x ⋀ y Bitwise AND x ⋁ y Bitwise OR ¬ x The negation of x. x ≪ s Shifting of x by s bits to the left. x ⋘ s Rotation of x by s bits to the left. 4 Bitwise Functions Function IF (x, y, z) (x ⋀ y) ⋁ ((¬ x) ⋀ z) XOR (x, y, z) x ⊕ y ⊕ z MAJ (x, y, z) (x ⋀ y) ⋁ (y ⋀ z) ⋁ (z ⋀ x) XNO (x, y, z) y ⊕ ((¬ z) ⋁ x) ‣ The functions above are all bitwise. 5 Hash Functions ‣ A hash function maps elements from a finite or infinite domain, into elements of a fixed size domain. 6 Attacks on Hash Functions ‣ Collision attack Find m and m’ ≠ m such that H(m) = H(m’). ‣ First pre-image attack Given h find m such that h = H(m). ‣ Second pre-image attack Given m find m’ ≠ m such that H(m) = H(m’). 7 Attack Complexities ‣ Collision attack Naïve complexity O(2n/2) due to the birthday paradox. ‣ First pre-image attack Naïve complexity O(2n) ‣ Second pre-image attack Naïve complexity O(2n) 8 Cryptographic Hash Functions ‣ It is desirable for a cryptographic hash function to be collision resistant, first pre-image resistant and second pre-image resistant. -

Modes of Operation for Compressed Sensing Based Encryption

Modes of Operation for Compressed Sensing based Encryption DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften Dr. rer. nat. vorgelegt von Robin Fay, M. Sc. eingereicht bei der Naturwissenschaftlich-Technischen Fakultät der Universität Siegen Siegen 2017 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Christoph Ruland 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Robert Fischer Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 14.06.2017 To Verena ... s7+OZThMeDz6/wjq29ACJxERLMATbFdP2jZ7I6tpyLJDYa/yjCz6OYmBOK548fer 76 zoelzF8dNf /0k8H1KgTuMdPQg4ukQNmadG8vSnHGOVpXNEPWX7sBOTpn3CJzei d3hbFD/cOgYP4N5wFs8auDaUaycgRicPAWGowa18aYbTkbjNfswk4zPvRIF++EGH UbdBMdOWWQp4Gf44ZbMiMTlzzm6xLa5gRQ65eSUgnOoZLyt3qEY+DIZW5+N s B C A j GBttjsJtaS6XheB7mIOphMZUTj5lJM0CDMNVJiL39bq/TQLocvV/4inFUNhfa8ZM 7kazoz5tqjxCZocBi153PSsFae0BksynaA9ZIvPZM9N4++oAkBiFeZxRRdGLUQ6H e5A6HFyxsMELs8WN65SCDpQNd2FwdkzuiTZ4RkDCiJ1Dl9vXICuZVx05StDmYrgx S6mWzcg1aAsEm2k+Skhayux4a+qtl9sDJ5JcDLECo8acz+RL7/ ovnzuExZ3trm+O 6GN9c7mJBgCfEDkeror5Af4VHUtZbD4vALyqWCr42u4yxVjSj5fWIC9k4aJy6XzQ cRKGnsNrV0ZcGokFRO+IAcuWBIp4o3m3Amst8MyayKU+b94VgnrJAo02Fp0873wa hyJlqVF9fYyRX+couaIvi5dW/e15YX/xPd9hdTYd7S5mCmpoLo7cqYHCVuKWyOGw ZLu1ziPXKIYNEegeAP8iyeaJLnPInI1+z4447IsovnbgZxM3ktWO6k07IOH7zTy9 w+0UzbXdD/qdJI1rENyriAO986J4bUib+9sY/2/kLlL7nPy5Kxg3 Et0Fi3I9/+c/ IYOwNYaCotW+hPtHlw46dcDO1Jz0rMQMf1XCdn0kDQ61nHe5MGTz2uNtR3bty+7U CLgNPkv17hFPu/lX3YtlKvw04p6AZJTyktsSPjubqrE9PG00L5np1V3B/x+CCe2p niojR2m01TK17/oT1p0enFvDV8C351BRnjC86Z2OlbadnB9DnQSP3XH4JdQfbtN8 BXhOglfobjt5T9SHVZpBbzhDzeXAF1dmoZQ8JhdZ03EEDHjzYsXD1KUA6Xey03wU uwnrpTPzD99cdQM7vwCBdJnIPYaD2fT9NwAHICXdlp0pVy5NH20biAADH6GQr4Vc -

Truncated Differential Analysis of Round-Reduced Roadrunner

Truncated Differential Analysis of Round-Reduced RoadRunneR Block Cipher Qianqian Yang1;2;3, Lei Hu1;2;??, Siwei Sun1;2, Ling Song1;2 1State Key Laboratory of Information Security, Institute of Information Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China 2Data Assurance and Communication Security Research Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China 3University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China {qqyang13,hu,swsun,lsong}@is.ac.cn Abstract. RoadRunneR is a small and fast bitslice lightweight block ci- pher for low cost 8-bit processors proposed by Adnan Baysal and S¨ahap S¸ahin in the LightSec 2015 conference. While most software efficient lightweight block ciphers lacking a security proof, RoadRunneR's secu- rity is provable against differential and linear attacks. RoadRunneR is a Feistel structure block cipher with 64-bit block size. RoadRunneR-80 is a vision with 80-bit key and 10 rounds, and RoadRunneR-128 is a vision with 128-bit key and 12 rounds. In this paper, we obtain 5-round truncated differentials of RoadRunneR-80 and RoadRunneR-128 with probability 2−56. Using the truncated differentials, we give a truncated differential attack on 7-round RoadRunneR-128 without whitening keys with data complexity of 255 chosen plaintexts, time complexity of 2121 encryptions and memory complexity of 268. This is first known attack on RoadRunneR block cipher. Keywords: Lightweight, Block Cipher, RoadRunneR, Truncated Dif- ferential Cryptanalysis 1 Introduction Recently, lightweight block ciphers, which could be widely used in small embed- ded devices such as RFIDs and sensor networks, are becoming more and more popular.