Oral History Interview with Martin Hellman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tarjan Transcript Final with Timestamps

A.M. Turing Award Oral History Interview with Robert (Bob) Endre Tarjan by Roy Levin San Mateo, California July 12, 2017 Levin: My name is Roy Levin. Today is July 12th, 2017, and I’m in San Mateo, California at the home of Robert Tarjan, where I’ll be interviewing him for the ACM Turing Award Winners project. Good afternoon, Bob, and thanks for spending the time to talk to me today. Tarjan: You’re welcome. Levin: I’d like to start by talking about your early technical interests and where they came from. When do you first recall being interested in what we might call technical things? Tarjan: Well, the first thing I would say in that direction is my mom took me to the public library in Pomona, where I grew up, which opened up a huge world to me. I started reading science fiction books and stories. Originally, I wanted to be the first person on Mars, that was what I was thinking, and I got interested in astronomy, started reading a lot of science stuff. I got to junior high school and I had an amazing math teacher. His name was Mr. Wall. I had him two years, in the eighth and ninth grade. He was teaching the New Math to us before there was such a thing as “New Math.” He taught us Peano’s axioms and things like that. It was a wonderful thing for a kid like me who was really excited about science and mathematics and so on. The other thing that happened was I discovered Scientific American in the public library and started reading Martin Gardner’s columns on mathematical games and was completely fascinated. -

Diamondoid Mechanosynthesis Prepared for the International Technology Roadmap for Productive Nanosystems

IMM White Paper Scanning Probe Diamondoid Mechanosynthesis Prepared for the International Technology Roadmap for Productive Nanosystems 1 August 2007 D.R. Forrest, R. A. Freitas, N. Jacobstein One proposed pathway to atomically precise manufacturing is scanning probe diamondoid mechanosynthesis (DMS): employing scanning probe technology for positional control in combination with novel reactive tips to fabricate atomically-precise diamondoid components under positional control. This pathway has its roots in the 1986 book Engines of Creation, in which the manufacture of diamondoid parts was proposed as a long-term objective by Drexler [1], and in the 1989 demonstration by Donald Eigler at IBM that individual atoms could be manipulated by a scanning tunelling microscope [2]. The proposed DMS-based pathway would skip the intermediate enabling technologies proposed by Drexler [1a, 1b, 1c] (these begin with polymeric structures and solution-phase synthesis) and would instead move toward advanced DMS in a more direct way. Although DMS has not yet been realized experimentally, there is a strong base of experimental results and theory that indicate it can be achieved in the near term. • Scanning probe positional assembly with single atoms has been successfully demonstrated in by different research groups for Fe and CO on Ag, Si on Si, and H on Si and CNHCH3. • Theoretical treatments of tip reactions show that carbon dimers1 can be transferred to diamond surfaces with high fidelity. • A study on tip design showed that many variations on a design turn out to be suitable for accurate carbon dimer placement. Therefore, efforts can be focused on the variations of tooltips of many kinds that are easier to synthesize. -

Chapter 3 – Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Chapter 3 –Block Ciphers and the Data Cryptography and Network Encryption Standard Security All the afternoon Mungo had been working on Stern's Chapter 3 code, principally with the aid of the latest messages which he had copied down at the Nevin Square drop. Stern was very confident. He must be well aware London Central knew about that drop. It was obvious Fifth Edition that they didn't care how often Mungo read their messages, so confident were they in the by William Stallings impenetrability of the code. —Talking to Strange Men, Ruth Rendell Lecture slides by Lawrie Brown Modern Block Ciphers Block vs Stream Ciphers now look at modern block ciphers • block ciphers process messages in blocks, each one of the most widely used types of of which is then en/decrypted cryptographic algorithms • like a substitution on very big characters provide secrecy /hii/authentication services – 64‐bits or more focus on DES (Data Encryption Standard) • stream ciphers process messages a bit or byte at a time when en/decrypting to illustrate block cipher design principles • many current ciphers are block ciphers – better analysed – broader range of applications Block vs Stream Ciphers Block Cipher Principles • most symmetric block ciphers are based on a Feistel Cipher Structure • needed since must be able to decrypt ciphertext to recover messages efficiently • bloc k cihiphers lklook like an extremely large substitution • would need table of 264 entries for a 64‐bit block • instead create from smaller building blocks • using idea of a product cipher 1 Claude -

1. Course Information Are Handed Out

6.826—Principles of Computer Systems 2006 6.826—Principles of Computer Systems 2006 course secretary's desk. They normally cover the material discussed in class during the week they 1. Course Information are handed out. Delayed submission of the solutions will be penalized, and no solutions will be accepted after Thursday 5:00PM. Students in the class will be asked to help grade the problem sets. Each week a team of students Staff will work with the TA to grade the week’s problems. This takes about 3-4 hours. Each student will probably only have to do it once during the term. Faculty We will try to return the graded problem sets, with solutions, within a week after their due date. Butler Lampson 32-G924 425-703-5925 [email protected] Policy on collaboration Daniel Jackson 32-G704 8-8471 [email protected] We encourage discussion of the issues in the lectures, readings, and problem sets. However, if Teaching Assistant you collaborate on problem sets, you must tell us who your collaborators are. And in any case, you must write up all solutions on your own. David Shin [email protected] Project Course Secretary During the last half of the course there is a project in which students will work in groups of three Maria Rebelo 32-G715 3-5895 [email protected] or so to apply the methods of the course to their own research projects. Each group will pick a Office Hours real system, preferably one that some member of the group is actually working on but possibly one from a published paper or from someone else’s research, and write: Messrs. -

Chapter 3 – Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Symmetric Cryptography Chapter 6 Block vs Stream Ciphers • Block ciphers process messages into blocks, each of which is then en/decrypted – Like a substitution on very big characters • 64-bits or more • Stream ciphers process messages a bit or byte at a time when en/decrypting – Many current ciphers are block ciphers • Better analyzed. • Broader range of applications. Block vs Stream Ciphers Block Cipher Principles • Block ciphers look like an extremely large substitution • Would need table of 264 entries for a 64-bit block • Arbitrary reversible substitution cipher for a large block size is not practical – 64-bit general substitution block cipher, key size 264! • Most symmetric block ciphers are based on a Feistel Cipher Structure • Needed since must be able to decrypt ciphertext to recover messages efficiently Ideal Block Cipher Substitution-Permutation Ciphers • in 1949 Shannon introduced idea of substitution- permutation (S-P) networks – modern substitution-transposition product cipher • These form the basis of modern block ciphers • S-P networks are based on the two primitive cryptographic operations we have seen before: – substitution (S-box) – permutation (P-box) (transposition) • Provide confusion and diffusion of message Diffusion and Confusion • Introduced by Claude Shannon to thwart cryptanalysis based on statistical analysis – Assume the attacker has some knowledge of the statistical characteristics of the plaintext • Cipher needs to completely obscure statistical properties of original message • A one-time pad does this Diffusion -

Cryptography: DH And

1 ì Key Exchange Secure Software Systems Fall 2018 2 Challenge – Exchanging Keys & & − 1 6(6 − 1) !"#ℎ%&'() = = = 15 & 2 2 The more parties in communication, ! $ the more keys that need to be securely exchanged Do we have to use out-of-band " # methods? (e.g., phone?) % Secure Software Systems Fall 2018 3 Key Exchange ì Insecure communica-ons ì Alice and Bob agree on a channel shared secret (“key”) that ì Eve can see everything! Eve doesn’t know ì Despite Eve seeing everything! ! " (alice) (bob) # (eve) Secure Software Systems Fall 2018 Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman, 4 “New directions in cryptography,” in IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, vol. 22, no. 6, Nov 1976. Proposed public key cryptography. Diffie-Hellman key exchange. Secure Software Systems Fall 2018 5 Diffie-Hellman Color Analogy (1) It’s easy to mix two colors: + = (2) Mixing two or more colors in a different order results in + + = the same color: + + = (3) Mixing colors is one-way (Impossible to determine which colors went in to produce final result) https://www.crypto101.io/ Secure Software Systems Fall 2018 6 Diffie-Hellman Color Analogy ! # " (alice) (eve) (bob) + + $ $ = = Mix Mix (1) Start with public color ▇ – share across network (2) Alice picks secret color ▇ and mixes it to get ▇ (3) Bob picks secret color ▇ and mixes it to get ▇ Secure Software Systems Fall 2018 7 Diffie-Hellman Color Analogy ! # " (alice) (eve) (bob) $ $ Mix Mix = = Eve can’t calculate ▇ !! (secret keys were never shared) (4) Alice and Bob exchange their mixed colors (▇,▇) (5) Eve will -

Nanorobot Construction Crews

Nanorobot Construction Crews Jaeseung Jeong, Ph.D Department of Bio and Brain engineering, KAIST Nanorobotics • Nanorobotics is the technology of creating machines or robots atltthit or close to the microscopi c scal lfe of a nanomet res (10-9 metres). More specifically, nanorobotics refers to the still largely ‘hypothetical’ nanotechnology engineering discipline of designing and building nanorobots. • Nanorobots ((,,nanobots, nanoids, nanites or nanonites ) would be typically devices ranging in size from 0.1-10 micrometers and constructed of nanoscale or molecular components. As no artificial non-biological nanorobots have yet been created, they remain a ‘hypothetical’ concept. • Another definition sometimes used is a robot which allows precision interactions with nanoscale objects , or can manipulate with nanoscale resolution. • Followingggpp this definition even a large apparatus such as an atomic force microscope can be considered a nanorobotic instrument when configured to perform nanomanipulation. • Also, macroscalble robots or mi crorob ots which can move wi th nanoscale precision can also be considered nanorobots. The T-1000 in Terminator 2: Judggyment Day • Since nanorobots would be microscopic in size , it would probably be necessary for very large numbers of them to work together to perform microscopic and macroscopic tasks. • These nanorobot swarms are fdifound in many sci ence fi fitiction stories, such as The T-1000 in Terminator 2: Judgment Day, nanomachine i n Meta l G ear So lid. • The word "nanobot" (also "nanite",,g, "nanogene", or "nanoant") is often used to indicate this fictional context and is a n info rma l o r eve n pejo rat ive term to refer to the engineering concept of nanorobots. -

Fall 2016 Dear Electrical Engineering Alumni and Friends, This Past

ABBAS EL GAMAL Fortinet Founders Chair of the Department of Electrical Engineering Hitachi America Professor Fall 2016 Dear Electrical Engineering Alumni and Friends, This past academic year was another very successful one for the department. We made great progress toward implementing the vision of our strategic plan (EE in the 21st Century, or EE21 for short), which I outlined in my letter to you last year. I am also proud to share some of the exciting research in the department and the significant recognitions our faculty have received. I will first briefly describe the progress we have made toward implementing our EE21 plan. Faculty hiring. The top priority in our strategic plan is hiring faculty with complementary vision and expertise and who enhance our faculty diversity. This past academic year, we conducted a junior faculty broad area search and participated in a School of Engineering wide search in the area of robotics. I am happy to report that Mary Wootters joined our faculty in September as an assistant professor jointly with Computer Science. Mary’s research focuses on applying probability to coding theory, signal processing, and randomized algorithms. She also explores quantum information theory and complexity theory. Mary was previously an NSF postdoctoral fellow in the CS department at Carnegie Mellon University. The robotics search yielded two top candidates. I will report on the final results of this search in my next year’s letter. Reinventing the undergraduate curriculum. We continue to innovate our undergraduate curriculum, introducing two new, exciting project-oriented courses: EE107: Embedded Networked Systems and EE267: Virtual Reality. -

Martin Hellman, Walker and Company, New York,1988, Pantheon Books, New York,1986

Risk Analysis of Nuclear Deterrence by Dr. Martin E. Hellman, New York Epsilon ’66 he first fundamental canon of The Code of A terrorist attack involving a nuclear weapon would Ethics for Engineers adopted by Tau Beta Pi be a catastrophe of immense proportions: “A 10-kiloton states that “Engineers shall hold paramount bomb detonated at Grand Central Station on a typical work the safety, health, and welfare of the public day would likely kill some half a million people, and inflict in the performance of their professional over a trillion dollars in direct economic damage. America Tduties.” When we design systems, we routinely use large and its way of life would be changed forever.” [Bunn 2003, safety factors to account for unforeseen circumstances. pages viii-ix]. The Golden Gate Bridge was designed with a safety factor The likelihood of such an attack is also significant. For- several times the anticipated load. This “over design” saved mer Secretary of Defense William Perry has estimated the bridge, along with the lives of the 300,000 people who the chance of a nuclear terrorist incident within the next thronged onto it in 1987 to celebrate its fiftieth anniver- decade to be roughly 50 percent [Bunn 2007, page 15]. sary. The weight of all those people presented a load that David Albright, a former weapons inspector in Iraq, was several times the design load1, visibly flattening the estimates those odds at less than one percent, but notes, bridge’s arched roadway. Watching the roadway deform, “We would never accept a situation where the chance of a bridge engineers feared that the span might collapse, but major nuclear accident like Chernobyl would be anywhere engineering conservatism saved the day. -

The Impetus to Creativity in Technology

The Impetus to Creativity in Technology Alan G. Konheim Professor Emeritus Department of Computer Science University of California Santa Barbara, California 93106 [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: We describe the technical developments ensuing from two well-known publications in the 20th century containing significant and seminal results, a paper by Claude Shannon in 1948 and a patent by Horst Feistel in 1971. Near the beginning, Shannon’s paper sets the tone with the statement ``the fundamental problem of communication is that of reproducing at one point either exactly or approximately a message selected *sent+ at another point.‛ Shannon’s Coding Theorem established the relationship between the probability of error and rate measuring the transmission efficiency. Shannon proved the existence of codes achieving optimal performance, but it required forty-five years to exhibit an actual code achieving it. These Shannon optimal-efficient codes are responsible for a wide range of communication technology we enjoy today, from GPS, to the NASA rovers Spirit and Opportunity on Mars, and lastly to worldwide communication over the Internet. The US Patent #3798539A filed by the IBM Corporation in1971 described Horst Feistel’s Block Cipher Cryptographic System, a new paradigm for encryption systems. It was largely a departure from the current technology based on shift-register stream encryption for voice and the many of the electro-mechanical cipher machines introduced nearly fifty years before. Horst’s vision directed to its application to secure the privacy of computer files. Invented at a propitious moment in time and implemented by IBM in automated teller machines for the Lloyds Bank Cashpoint System. -

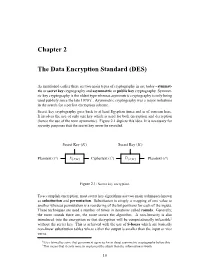

Chapter 2 the Data Encryption Standard (DES)

Chapter 2 The Data Encryption Standard (DES) As mentioned earlier there are two main types of cryptography in use today - symmet- ric or secret key cryptography and asymmetric or public key cryptography. Symmet- ric key cryptography is the oldest type whereas asymmetric cryptography is only being used publicly since the late 1970’s1. Asymmetric cryptography was a major milestone in the search for a perfect encryption scheme. Secret key cryptography goes back to at least Egyptian times and is of concern here. It involves the use of only one key which is used for both encryption and decryption (hence the use of the term symmetric). Figure 2.1 depicts this idea. It is necessary for security purposes that the secret key never be revealed. Secret Key (K) Secret Key (K) ? ? - - - - Plaintext (P ) E{P,K} Ciphertext (C) D{C,K} Plaintext (P ) Figure 2.1: Secret key encryption. To accomplish encryption, most secret key algorithms use two main techniques known as substitution and permutation. Substitution is simply a mapping of one value to another whereas permutation is a reordering of the bit positions for each of the inputs. These techniques are used a number of times in iterations called rounds. Generally, the more rounds there are, the more secure the algorithm. A non-linearity is also introduced into the encryption so that decryption will be computationally infeasible2 without the secret key. This is achieved with the use of S-boxes which are basically non-linear substitution tables where either the output is smaller than the input or vice versa. 1It is claimed by some that government agencies knew about asymmetric cryptography before this. -

Diffie and Hellman Receive 2015 Turing Award Rod Searcey/Stanford University

Diffie and Hellman Receive 2015 Turing Award Rod Searcey/Stanford University. Linda A. Cicero/Stanford News Service. Whitfield Diffie Martin E. Hellman ernment–private sector relations, and attracts billions of Whitfield Diffie, former chief security officer of Sun Mi- dollars in research and development,” said ACM President crosystems, and Martin E. Hellman, professor emeritus Alexander L. Wolf. “In 1976, Diffie and Hellman imagined of electrical engineering at Stanford University, have been a future where people would regularly communicate awarded the 2015 A. M. Turing Award of the Association through electronic networks and be vulnerable to having for Computing Machinery for their critical contributions their communications stolen or altered. Now, after nearly to modern cryptography. forty years, we see that their forecasts were remarkably Citation prescient.” The ability for two parties to use encryption to commu- “Public-key cryptography is fundamental for our indus- nicate privately over an otherwise insecure channel is try,” said Andrei Broder, Google Distinguished Scientist. fundamental for billions of people around the world. On “The ability to protect private data rests on protocols for a daily basis, individuals establish secure online connec- confirming an owner’s identity and for ensuring the integ- tions with banks, e-commerce sites, email servers, and the rity and confidentiality of communications. These widely cloud. Diffie and Hellman’s groundbreaking 1976 paper, used protocols were made possible through the ideas and “New Directions in Cryptography,” introduced the ideas of methods pioneered by Diffie and Hellman.” public-key cryptography and digital signatures, which are Cryptography is a practice that facilitates communi- the foundation for most regularly used security protocols cation between two parties so that the communication on the Internet today.