Chapter 3 – Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feistel Like Construction of Involutory Binary Matrices with High Branch Number

Feistel Like Construction of Involutory Binary Matrices With High Branch Number Adnan Baysal1,2, Mustafa C¸oban3, and Mehmet Ozen¨ 3 1TUB¨ ITAK_ - BILGEM,_ PK 74, 41470, Gebze, Kocaeli, Turkey, [email protected] 2Kocaeli University, Department of Computer Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Institute of Science, 41380, Umuttepe, Kocaeli, Turkey 3Sakarya University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Department of Mathematics, Sakarya, Turkey, [email protected], [email protected] August 4, 2016 Abstract In this paper, we propose a generic method to construct involutory binary matrices from a three round Feistel scheme with a linear round function. We prove bounds on the maximum achievable branch number (BN) and the number of fixed points of our construction. We also define two families of efficiently implementable round functions to be used in our method. The usage of these families in the proposed method produces matrices achieving the proven bounds on branch numbers and fixed points. Moreover, we show that BN of the transpose matrix is the same with the original matrix for the function families we defined. Some of the generated matrices are Maximum Distance Binary Linear (MDBL), i.e. matrices with the highest achievable BN. The number of fixed points of the generated matrices are close to the expected value for a random involution. Generated matrices are especially suitable for utilising in bitslice block ciphers and hash functions. They can be implemented efficiently in many platforms, from low cost CPUs to dedicated hardware. Keywords: Diffusion layer, bitslice cipher, hash function, involution, MDBL matrices, Fixed points. 1 Introduction Modern block ciphers and hash functions use two basic layers iteratively to provide security: confusion and diffusion. -

Block Ciphers

Block Ciphers Chester Rebeiro IIT Madras CR STINSON : chapters 3 Block Cipher KE KD untrusted communication link Alice E D Bob #%AR3Xf34^$ “Attack at Dawn!!” message encryption (ciphertext) decryption “Attack at Dawn!!” Encryption key is the same as the decryption key (KE = K D) CR 2 Block Cipher : Encryption Key Length Secret Key Plaintext Ciphertext Block Cipher (Encryption) Block Length • A block cipher encryption algorithm encrypts n bits of plaintext at a time • May need to pad the plaintext if necessary • y = ek(x) CR 3 Block Cipher : Decryption Key Length Secret Key Ciphertext Plaintext Block Cipher (Decryption) Block Length • A block cipher decryption algorithm recovers the plaintext from the ciphertext. • x = dk(y) CR 4 Inside the Block Cipher PlaintextBlock (an iterative cipher) Key Whitening Round 1 key1 Round 2 key2 Round 3 key3 Round n keyn Ciphertext Block • Each round has the same endomorphic cryptosystem, which takes a key and produces an intermediate ouput • Size of the key is huge… much larger than the block size. CR 5 Inside the Block Cipher (the key schedule) PlaintextBlock Secret Key Key Whitening Round 1 Round Key 1 Round 2 Round Key 2 Round 3 Round Key 3 Key Expansion Expansion Key Key Round n Round Key n Ciphertext Block • A single secret key of fixed size used to generate ‘round keys’ for each round CR 6 Inside the Round Function Round Input • Add Round key : Add Round Key Mixing operation between the round input and the round key. typically, an ex-or operation Confusion Layer • Confusion layer : Makes the relationship between round Diffusion Layer input and output complex. -

Chapter 3 – Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Symmetric Cryptography Chapter 6 Block vs Stream Ciphers • Block ciphers process messages into blocks, each of which is then en/decrypted – Like a substitution on very big characters • 64-bits or more • Stream ciphers process messages a bit or byte at a time when en/decrypting – Many current ciphers are block ciphers • Better analyzed. • Broader range of applications. Block vs Stream Ciphers Block Cipher Principles • Block ciphers look like an extremely large substitution • Would need table of 264 entries for a 64-bit block • Arbitrary reversible substitution cipher for a large block size is not practical – 64-bit general substitution block cipher, key size 264! • Most symmetric block ciphers are based on a Feistel Cipher Structure • Needed since must be able to decrypt ciphertext to recover messages efficiently Ideal Block Cipher Substitution-Permutation Ciphers • in 1949 Shannon introduced idea of substitution- permutation (S-P) networks – modern substitution-transposition product cipher • These form the basis of modern block ciphers • S-P networks are based on the two primitive cryptographic operations we have seen before: – substitution (S-box) – permutation (P-box) (transposition) • Provide confusion and diffusion of message Diffusion and Confusion • Introduced by Claude Shannon to thwart cryptanalysis based on statistical analysis – Assume the attacker has some knowledge of the statistical characteristics of the plaintext • Cipher needs to completely obscure statistical properties of original message • A one-time pad does this Diffusion -

Lecture Four

Lecture Four Today’s Topics . Historic Symmetric ciphers . Modern symmetric ciphers . DES, AES . Asymmetric ciphers . RSA . Next class: Protocols Example Ciphers . Shift cipher: each plaintext characters is replaced by a character k to the right. (When k=3, it’s a Caesar cipher). “Watch out for Brutus!” => “Jngpu bhg sbe Oehghf!” . Only 25 choices! Not hard to break by brute force. Substitution Cipher: each character in plaintext is replaced by a corresponding character of ciphertext. E.g., cryptograms in newspapers. plaintext code: a b c d e f g h i f k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z ciphertext code: m n b v c x z a s d f g h j k l p o i u y t r e w q . 26! Possible pairs. Is is really that hard to break? Substitution ciphers . The Caesar cipher has a small key space, but doesn’t create a statistical independence between the plaintext and the ciphertext. The best ciphers allow no statistical attacks, thereby forcing a brute force, exhaustive search; all the security lies with the key space. As cryptographic algorithms matured, the statistical independence between the plaintext and cipher text increased. Ciphers . The caesar cipher, hill cipher, and playfair cipher all work with a single alphabet for doing substitutions . They are monoalphabetic substitutions. A more complex (and more robust) alternative is to use different substitution mappings on various portions of the plaintext. Polyalphabetic substitutions. More ciphers . Vigenère cipher: each character of plaintext is encrypted with a different a cipher key. -

A Tutorial on the Implementation of Block Ciphers: Software and Hardware Applications

A Tutorial on the Implementation of Block Ciphers: Software and Hardware Applications Howard M. Heys Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, Canada email: [email protected] Dec. 10, 2020 2 Abstract In this article, we discuss basic strategies that can be used to implement block ciphers in both software and hardware environments. As models for discussion, we use substitution- permutation networks which form the basis for many practical block cipher structures. For software implementation, we discuss approaches such as table lookups and bit-slicing, while for hardware implementation, we examine a broad range of architectures from high speed structures like pipelining, to compact structures based on serialization. To illustrate different implementation concepts, we present example data associated with specific methods and discuss sample designs that can be employed to realize different implementation strategies. We expect that the article will be of particular interest to researchers, scientists, and engineers that are new to the field of cryptographic implementation. 3 4 Terminology and Notation Abbreviation Definition SPN substitution-permutation network IoT Internet of Things AES Advanced Encryption Standard ECB electronic codebook mode CBC cipher block chaining mode CTR counter mode CMOS complementary metal-oxide semiconductor ASIC application-specific integrated circuit FPGA field-programmable gate array Table 1: Abbreviations Used in Article 5 6 Variable Definition B plaintext/ciphertext block size (also, size of cipher state) κ number -

Symmetric Key Ciphers Objectives

Symmetric Key Ciphers Debdeep Mukhopadhyay Assistant Professor Department of Computer Science and Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur INDIA -721302 Objectives • Definition of Symmetric Types of Symmetric Key ciphers – Modern Block Ciphers • Full Size and Partial Size Key Ciphers • Components of a Modern Block Cipher – PBox (Permutation Box) – SBox (Substitution Box) –Swap – Properties of the Exclusive OR operation • Diffusion and Confusion • Types of Block Ciphers: Feistel and non-Feistel ciphers D. Mukhopadhyay Crypto & Network Security IIT Kharagpur 1 Symmetric Key Setting Communication Message Channel Message E D Ka Kb Bob Alice Assumptions Eve Ka is the encryption key, Kb is the decryption key. For symmetric key ciphers, Ka=Kb - Only Alice and Bob knows Ka (or Kb) - Eve has access to E, D and the Communication Channel but does not know the key Ka (or Kb) Types of symmetric key ciphers • Block Ciphers: Symmetric key ciphers, where a block of data is encrypted • Stream Ciphers: Symmetric key ciphers, where block size=1 D. Mukhopadhyay Crypto & Network Security IIT Kharagpur 2 Block Ciphers Block Cipher • A symmetric key modern cipher encrypts an n bit block of plaintext or decrypts an n bit block of ciphertext. •Padding: – If the message has fewer than n bits, padding must be done to make it n bits. – If the message size is not a multiple of n, then it should be divided into n bit blocks and the last block should be padded. D. Mukhopadhyay Crypto & Network Security IIT Kharagpur 3 Full Size Key Ciphers • Transposition Ciphers: – Involves rearrangement of bits, without changing value. – Consider an n bit cipher – How many such rearrangements are possible? •n! – How many key bits are necessary? • ceil[log2 (n!)] Full Size Key Ciphers • Substitution Ciphers: – It does not transpose bits, but substitutes values – Can we model this as a permutation? – Yes. -

The Impetus to Creativity in Technology

The Impetus to Creativity in Technology Alan G. Konheim Professor Emeritus Department of Computer Science University of California Santa Barbara, California 93106 [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: We describe the technical developments ensuing from two well-known publications in the 20th century containing significant and seminal results, a paper by Claude Shannon in 1948 and a patent by Horst Feistel in 1971. Near the beginning, Shannon’s paper sets the tone with the statement ``the fundamental problem of communication is that of reproducing at one point either exactly or approximately a message selected *sent+ at another point.‛ Shannon’s Coding Theorem established the relationship between the probability of error and rate measuring the transmission efficiency. Shannon proved the existence of codes achieving optimal performance, but it required forty-five years to exhibit an actual code achieving it. These Shannon optimal-efficient codes are responsible for a wide range of communication technology we enjoy today, from GPS, to the NASA rovers Spirit and Opportunity on Mars, and lastly to worldwide communication over the Internet. The US Patent #3798539A filed by the IBM Corporation in1971 described Horst Feistel’s Block Cipher Cryptographic System, a new paradigm for encryption systems. It was largely a departure from the current technology based on shift-register stream encryption for voice and the many of the electro-mechanical cipher machines introduced nearly fifty years before. Horst’s vision directed to its application to secure the privacy of computer files. Invented at a propitious moment in time and implemented by IBM in automated teller machines for the Lloyds Bank Cashpoint System. -

Chapter 2 the Data Encryption Standard (DES)

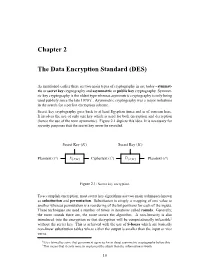

Chapter 2 The Data Encryption Standard (DES) As mentioned earlier there are two main types of cryptography in use today - symmet- ric or secret key cryptography and asymmetric or public key cryptography. Symmet- ric key cryptography is the oldest type whereas asymmetric cryptography is only being used publicly since the late 1970’s1. Asymmetric cryptography was a major milestone in the search for a perfect encryption scheme. Secret key cryptography goes back to at least Egyptian times and is of concern here. It involves the use of only one key which is used for both encryption and decryption (hence the use of the term symmetric). Figure 2.1 depicts this idea. It is necessary for security purposes that the secret key never be revealed. Secret Key (K) Secret Key (K) ? ? - - - - Plaintext (P ) E{P,K} Ciphertext (C) D{C,K} Plaintext (P ) Figure 2.1: Secret key encryption. To accomplish encryption, most secret key algorithms use two main techniques known as substitution and permutation. Substitution is simply a mapping of one value to another whereas permutation is a reordering of the bit positions for each of the inputs. These techniques are used a number of times in iterations called rounds. Generally, the more rounds there are, the more secure the algorithm. A non-linearity is also introduced into the encryption so that decryption will be computationally infeasible2 without the secret key. This is achieved with the use of S-boxes which are basically non-linear substitution tables where either the output is smaller than the input or vice versa. 1It is claimed by some that government agencies knew about asymmetric cryptography before this. -

Confusion and Diffusion

Confusion and Diffusion Ref: William Stallings, Cryptography and Network Security, 3rd Edition, Prentice Hall, 2003 Confusion and Diffusion 1 Statistics and Plaintext • Suppose the frequency distribution of plaintext in a human-readable message in some language is known. • Or suppose there are known words or phrases that are used in the plaintext message. • A cryptanalysist can use this information to break a cryptographic algorithm. Confusion and Diffusion 2 Changing Statistics • Claude Shannon suggested that to complicate statistical attacks, the cryptographer could dissipate the statistical structure of the plaintext in the long range statistics of the ciphertext. • Shannon called this process diffusion . Confusion and Diffusion 3 Changing Statistics (p.2) • Diffusion can be accomplished by having many plaintext characters affect each ciphertext character. • An example of diffusion is the encryption of a message M=m 1,m 2,... using a an averaging: y n= ∑i=1,k mn+i (mod26). Confusion and Diffusion 4 Changing Statistics (p.3) • In binary block ciphers, such as the Data Encryption Standard (DES), diffusion can be accomplished using permutations on data, and then applying a function to the permutation to produce ciphertext. Confusion and Diffusion 5 Complex Use of a Key • Diffusion complicates the statistics of the ciphertext, and makes it difficult to discover the key of the encryption process. • The process of confusion , makes the use of the key so complex, that even when an attacker knows the statistics, it is still difficult to deduce the key. Confusion and Diffusion 6 Complex Use of a Key(p.2) • Confusion can be accomplished by using a complex substitution algorithm. -

Network Security Chapter 8

Network Security Chapter 8 Network security problems can be divided roughly into 4 closely intertwined areas: secrecy (confidentiality), authentication, nonrepudiation, and integrity control. Question: what does non-repudiation mean? What does “integrity” mean? • Cryptography • Symmetric-Key Algorithms • Public-Key Algorithms • Digital Signatures • Management of Public Keys • Communication Security • Authentication Protocols • Email Security -- skip • Web Security • Social Issues -- skip Revised: August 2011 CN5E by Tanenbaum & Wetherall, © Pearson Education-Prentice Hall and D. Wetherall, 2011 Network Security Security concerns a variety of threats and defenses across all layers Application Authentication, Authorization, and non-repudiation Transport End-to-end encryption Network Firewalls, IP Security Link Packets can be encrypted on data link layer basis Physical Wireless transmissions can be encrypted CN5E by Tanenbaum & Wetherall, © Pearson Education-Prentice Hall and D. Wetherall, 2011 Network Security (1) Some different adversaries and security threats • Different threats require different defenses CN5E by Tanenbaum & Wetherall, © Pearson Education-Prentice Hall and D. Wetherall, 2011 Cryptography Cryptography – 2 Greek words meaning “Secret Writing” Vocabulary: • Cipher – character-for-character or bit-by-bit transformation • Code – replaces one word with another word or symbol Cryptography is a fundamental building block for security mechanisms. • Introduction » • Substitution ciphers » • Transposition ciphers » • One-time pads -

Outline Block Ciphers

Block Ciphers: DES, AES Guevara Noubir http://www.ccs.neu.edu/home/noubir/Courses/CSG252/F04 Textbook: —Cryptography: Theory and Applications“, Douglas Stinson, Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, 2002 Reading: Chapter 3 Outline n Substitution-Permutation Networks n Linear Cryptanalysis n Differential Cryptanalysis n DES n AES n Modes of Operation CSG252 Classical Cryptography 2 Block Ciphers n Typical design approach: n Product cipher: substitutions and permutations n Leading to a non-idempotent cipher n Iteration: n Nr: number of rounds → 1 2 Nr n Key schedule: k k , k , …, k , n Subkeys derived according to publicly known algorithm i n w : state n Round function r r-1 r n w = g(w , k ) 0 n w : plaintext x n Required property of g: ? n Encryption and Decryption sequence CSG252 Classical Cryptography 3 1 SPN: Substitution Permutation Networks n SPN: special type of iterated cipher (w/ small change) n Block length: l x m n x = x(1) || x(2) || … || x(m) n x(i) = (x(i-1)l+1, …, xil) n Components: π l → l n Substitution cipher s: {0, 1} {0, 1} π → n Permutation cipher (S-box) P: {1, …, lm} {1, …, lm} n Outline: n Iterate Nr times: m substitutions; 1 permutation; ⊕ sub-key; n Definition of SPN cryptosytems: n P = ?; C = ?; K ⊆ ?; n Algorithm: n Designed to allow decryption using the same algorithm n What are the parameters of the decryption algorithm? CSG252 Classical Cryptography 4 SPN: Example n l = m = 4; Nr = 4; n Key schedule: n k: (k1, …, k32) 32 bits r n k : (k4r-3, …, k4r+12) z 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F π S(z) E 4 D 1 2 F B 8 3 A 6 C -

Symmetric Key Cryptosystems Definition

Symmetric Key Cryptosystems Debdeep Mukhopadhyay IIT Kharagpur Definition • Alice and Bob has the same key to encrypt as well as to decrypt • The key is shared via a “secured channel” • Symmetric Ciphers are of two types: – Block : The plaintext is encrypted in blocks – Stream: The block length is 1 • Symmetric Ciphers are used for bulk encryption, as they have better performance than their asymmetric counter-part. 1 Block Ciphers What we have learnt from history? • Observation: If we have a cipher C1=(P,P,K1,e1,d1) and a cipher C2 (P,P,K2,e2,d2). • We define the product cipher as C1xC2 by the process of first applying C1 and then C2 • Thus C1xC2=(P,P,K1xK2,e,d) • Any key is of the form: (k1,k2) and e=e2(e1(x,k1),k2). Likewise d is defined. Note that the product rule is always associative 2 Question: • Thus if we compute product of ciphers, does the cipher become stronger? – The key space become larger –2nd Thought: Does it really become larger. • Let us consider the product of a 1. multiplicative cipher (M): y=ax, where a is co-prime to 26 //Plain Texts are characters 2. shift cipher (S) : y=x + k Is MxS=SxM? • MxS: y=ax+k : key=(a,k). This is an affine cipher, as total size of key space is 312. • SxM: y=a(x+k)=ax+ak – Now, since gcd(a,26)=1, this is also an affine cipher. – key = (a,ak) – As gcd(a,26)=1, a-1 exists. There is a one-one relation between ak and k.