A Case of Mandera County, Kenya (1967-2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mandera County Hiv and Aids Strategic Plan 2016-2019

MANDERA COUNTY HIV AND AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN 2016-2019 “A healthy and productive population” i MANDERA COUNTY HIV AND AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN 2016-2019 “A healthy and productive population” Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used for commercial purposes or for profit. iv MANDERA COUNTY HIV & AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN (2016- 2019) Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations vii Foreword viii Preface ix Acknowledgement x CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Information xii 1.2 Demographic characteristics 2 1.3 Land availability and use 2 1.3 Purpose of the HIV Plan 1.4 Process of developing the HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 1.5 Guiding principles CHAPTER TWO: HIV STATUS IN THE COUNTY 2.1 County HIV Profiles 5 2.2 Priority population 6 2.3 Gaps and challenges analysis 6 CHAPTER THREE: PURPOSE OF Mcasp, strateGIC PLAN DEVELOPMENT process AND THE GUIDING PRINCIPLES 8 3.1 Purpose of the HIV Plan 9 3.2 Process of developing the HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 9 3.3 Guiding principles 9 CHAPTER FOUR: VISION, GOALS, OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS 10 4.1 The vision, goals and objectives of the county 11 4.2 Strategic directions 12 4.2.1 Strategic direction 1: Reducing new HIV infection 12 4.2.2 Strategic direction 2: Improving health outcomes and wellness of people living with HIV and AIDS 14 4.2.3 Strategic Direction 3: Using human rights based approach1 to facilitate access to services 16 4.2.4 Strategic direction 4: Strengthening Integration of community and health systems 18 4.2.5 Strategic Direction 5: Strengthen Research innovation and information management to meet the Mandera County HIV Strategy goals. -

Usaid Kenya Niwajibu Wetu (Niwetu) Fy 2018 Q3 Progress Report

USAID KENYA NIWAJIBU WETU (NIWETU) FY 2018 Q3 PROGRESS REPORT JULY 2018 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI Global, LLC. USAID/KENYA NIWAJIBU WETU (NIWETU) PROGRESS REPORT FOR Q3 FY 2018 1 USAID KENYA NIWAJIBU WETU (NIWETU) FY 2018 Q3 PROGRESS REPORT 1 April – 30 June 2018 Award No: AID-OAA-I-13-00013/AID-615-TO-16-00010 Prepared for John Langlois United States Agency for International Development/Kenya C/O American Embassy United Nations Avenue, Gigiri P.O. Box 629, Village Market 00621 Nairobi, Kenya Prepared by DAI Global, LLC 4th Floor, Mara 2 Building Eldama Park Nairobi, Kenya DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. USAID/KENYA NIWAJIBU WETU (NIWETU) PROGRESS REPORT FOR Q3 FY 2018 2 CONTENTS I. NIWETU EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................... vii II. KEY ACHIEVEMENTS (Qualitative Impact) ................................................................ 9 III. ACTIVITY PROGRESS (Quantitative Impact) .......................................................... 20 III. ACTIVITY PROGRESS (QUANTITATIVE IMPACT) ............................................... 20 IV. CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES ................................................................. 39 V. PERFORMANCE MONITORING ............................................................................... -

County Name County Code Location

COUNTY NAME COUNTY CODE LOCATION MOMBASA COUNTY 001 BANDARI COLLEGE KWALE COUNTY 002 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT MATUGA KILIFI COUNTY 003 PWANI UNIVERSITY TANA RIVER COUNTY 004 MAU MAU MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL LAMU COUNTY 005 LAMU FORT HALL TAITA TAVETA 006 TAITA ACADEMY GARISSA COUNTY 007 KENYA NATIONAL LIBRARY WAJIR COUNTY 008 RED CROSS HALL MANDERA COUNTY 009 MANDERA ARIDLANDS MARSABIT COUNTY 010 ST. STEPHENS TRAINING CENTRE ISIOLO COUNTY 011 CATHOLIC MISSION HALL, ISIOLO MERU COUNTY 012 MERU SCHOOL THARAKA-NITHI 013 CHIAKARIGA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL EMBU COUNTY 014 KANGARU GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KITUI COUNTY 015 MULTIPURPOSE HALL KITUI MACHAKOS COUNTY 016 MACHAKOS TEACHERS TRAINING COLLEGE MAKUENI COUNTY 017 WOTE TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE NYANDARUA COUNTY 018 ACK CHURCH HALL, OL KALAU TOWN NYERI COUNTY 019 NYERI PRIMARY SCHOOL KIRINYAGA COUNTY 020 ST.MICHAEL GIRLS BOARDING MURANGA COUNTY 021 MURANG'A UNIVERSITY COLLEGE KIAMBU COUNTY 022 KIAMBU INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY TURKANA COUNTY 023 LODWAR YOUTH POLYTECHNIC WEST POKOT COUNTY 024 MTELO HALL KAPENGURIA SAMBURU COUNTY 025 ALLAMANO HALL PASTORAL CENTRE, MARALAL TRANSZOIA COUNTY 026 KITALE MUSEUM UASIN GISHU 027 ELDORET POLYTECHNIC ELGEYO MARAKWET 028 IEBC CONSTITUENCY OFFICE - ITEN NANDI COUNTY 029 KAPSABET BOYS HIGH SCHOOL BARINGO COUNTY 030 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT, KABARNET LAIKIPIA COUNTY 031 NANYUKI HIGH SCHOOL NAKURU COUNTY 032 NAKURU HIGH SCHOOL NAROK COUNTY 033 MAASAI MARA UNIVERSITY KAJIADO COUNTY 034 MASAI TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE KERICHO COUNTY 035 KERICHO TEA SEC. SCHOOL -

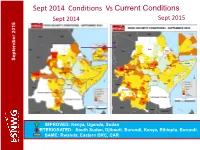

FSNWG Presentation

Sept 2014 Conditions Vs Current Conditions Sept 2015 Sept 2014 September 2015 September September September 2015 IMPROVED: Kenya, Uganda, Sudan DETERIORATED: South Sudan, Djibouti, Burundi, Kenya, Ethiopia, Burundi. SAME: Rwanda, Eastern DRC, CAR Current Conditions: Regional Highlights • Crisis and emergency food insecurity remains a concern in parts of DRC, CAR, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, parts of Karamoja, Darfur in Sudan, IDP sites in Somalia; September 2015 September • An estimated 17.9 people may be facing food insecurity in the region. • Dry conditions in pastoral areas of Ethiopia, Djibouti and Sudan are expected to continue till Dec (GHACOF, Aug.). • Conflicts/political tension remains a key driver for food insecurity in the region (e.g South Sudan, Burundi, CAR, eastern DRC and Somalia. • El Nino expected to lead to above average rainfall in some areas leading to improved food security outcomes but also localised flooding but depressed rainfalls in others persisting stressed/ food insecurity conditions General improvement in food security situation in the region. However, some deterioration seen in pastoral areas and an estimated 17.9M people in need of humanitarian assistance. Current Conditions – Burundi Burundi WFP, IPC (priliminary) •Generally food security conditions is good due to the season B harvest. September 2015 September •About 100,000 are considered in food insecurity crisis. •Significant number of farming population have fled to neigboring countries (UNHCR) due to the political crisis •The political crisis negatively affected Economic Activities in the country, particularly the capital Bujumbura. Trade in agricultural comoditities fell by about 50%. •The lean period is expected to start in September, is likely be exacerbated by the negative effects of the current crisis Food security relatively stable due to Season B production though expected to remain stressed to December. -

Abstracts 2019 July Graduation

ABSTRACTS 2019 JULY GRADUATION PHD SCHOOL OF BUSINESS FINANCING DECISIONS AND SHAREHOLDER VALUE CREATIONOF NON- FINANCIAL FIRMS QUOTED AT THE NAIROBI SECURITIES EXCHANGE, KENYA KARIUKI G MUTHONI-PHD Department: Business Administration Supervisors: Dr. Ambrose O. Jagongo Dr. Joseph Muniu Shareholder value creation and profit maximizing are among the primary objectives of a firm. Shareholder value creation focuses more on long term sustainability of returns and not just profitability. Rational investors expect good long term yield of their investment. Corporate financial decisions play an imperative role in general performance of a company and shareholder value creation. There have been a number of firms facing financial crisis among them; Mumias Sugar Ltd, Uchumi Supermarkets Ltd and Kenya Airways Ltd. All these companies are quoted at the Nairobi Securities Exchange. Due to declining performance of these companies, share prices have been dropping and shareholders do not receive dividends. This study investigated the effects of financing decisions on shareholder value creation of non- financial firms quoted at NSE for the period 2008-2014. The study was guided by various finance models; which include, Modigliani and Miller, Pecking Order Theory, Agency Free Flow Theory, Market Timing Theory and Capital Asset Pricing Model. The study used general and empirical models from previous studies as a basis for studying specific models which were modified to suit the current study. The study was guided by the positivism philosophy. The study employed explanatory design which is non-experimental. Census design was used as the number of non- financial firms at the time of the study was 40 companies. The data was gathered from NSE handbooks and CMA publications comprising of annual financial statements, income statements and accompanying notes. -

INSULT to INJURY the 2014 Lamu and Tana River Attacks and Kenya’S Abusive Response

INSULT TO INJURY The 2014 Lamu and Tana River Attacks and Kenya’s Abusive Response HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH hrw.org www.khrc.or.ke Insult to Injury The 2014 Lamu and Tana River Attacks and Kenya’s Abusive Response Copyright © 2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-32446 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2015 978-1-6231-32446 Insult to Injury The 2014 Lamu and Tana River Attacks and Kenya’s Abusive Response Map of Kenya and Coast Region ........................................................................................ i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .......................................................................................................... -

Violent Extremism and Clan Dynamics in Kenya

[PEACEW RKS [ VIOLENT EXTREMISM AND CLAN DYNAMICS IN KENYA Ngala Chome ABOUT THE REPORT This report, which is derived from interviews across three Kenyan counties, explores the relationships between resilience and risk to clan violence and to violent extrem- ism in the northeast region of the country. The research was funded by a grant from the United States Agency for International Development through the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), which collaborated with Sahan Africa in conducting the study. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Ngala Chome is a former researcher at Sahan Research, where he led a number of countering violent extremism research projects over the past year. Chome has published articles in Critical African Studies, Journal of Eastern Afri- can Studies, and Afrique Contemporine. He is currently a doctoral researcher in African history at Durham University. The author would like to thank Abdulrahman Abdullahi for his excellent research assistance, Andiah Kisia and Lauren Van Metre for helping frame the analysis, the internal reviewers, and two external reviewers for their useful and helpful comments. The author bears responsibility for the final analysis and conclusion. Cover photo: University students join a demonstration condemning the gunmen attack at the Garissa University campus in the Kenyan coastal port city of Mombasa on April 8, 2015. (REUTERS/Joseph Okanga/ IMAGE ID: RTR4WI4K) The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Ave., NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. -

Arboviruses of Human Health Significance in Kenya Atoni E1,2

Arboviruses of Human Health significance in Kenya Atoni E1,2#, Waruhiu C1,2#, Nganga S1,2, Xia H1, Yuan Z1 1. Key Laboratory of Special Pathogens, Wuhan Institute of Virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430071, China 2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100049, China #Authors contributed equally to this work Correspondence: Zhiming Yuan, [email protected]; Tel.: +86-2787198195 Summary In tropical and developing countries, arboviruses cause emerging and reemerging infectious diseases. The East African region has experienced several outbreaks of Rift valley fever virus, Dengue virus, Chikungunya virus and Yellow fever virus. In Kenya, data from serological studies and mosquito isolation studies have shown a wide distribution of arboviruses throughout the country, implying the potential risk of these viruses to local public health. However, current estimates on circulating arboviruses in the country are largely underestimated due to lack of continuous and reliable countrywide surveillance and reporting systems on arboviruses and disease vectors and the lack of proper clinical screening methods and modern facilities. In this review, we discuss arboviruses of human health importance in Kenya by outlining the arboviruses that have caused outbreaks in the country, alongside those that have only been detected from various serological studies performed. Based on our analysis, at the end we provide workable technical and policy-wise recommendations for management of arboviruses and arboviral vectors in Kenya. [Afr J Health Sci. 2018; 31(1):121-141] and mortality. Recently, the outbreak of Zika virus Introduction became a global public security event, due to its Arthropod-borne viruses (Arboviruses) are a cause ability to cause congenital brain abnormalities, of significant human and animal diseases worldwide. -

Interim Independent Boundaries Review Commission (IIBRC)

REPUBLIC OF KENYA The Report of the Interim Independent Boundaries Review Commission (IIBRC) Delimitation of Constituencies and Recommendations on Local Authority Electoral Units and Administrative Boundaries for Districts and Other Units Presented to: His Excellency Hon. Mwai Kibaki, C.G.H., M.P. President and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Kenya The Rt. Hon. Raila Amolo Odinga, E.G.H., M.P. Prime Minister of the Republic of Kenya The Hon. Kenneth Marende, E.G.H., M.P. Speaker of the National Assembly 27th November, 2010 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................... i Letter of Submission .................................................................................................................................... iv Acronyms and Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................... vii Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................... viii 1.0 Chapter One: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Aftermath of the General Elections of 2007 ..................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Statement of Principles on Long-term Issues and Solutions ........................................................ -

Export Agreement Coding (PDF)

Peace Agreement Access Tool PA-X www.peaceagreements.org Country/entity Kenya Region Africa (excl MENA) Agreement name Modogashe Declaration (III) Date 08/04/2011 Agreement status Multiparty signed/agreed Interim arrangement No Agreement/conflict level Intrastate/local conflict ( Kenyan Post-Electoral Violence (2007 - 2008) ) Stage Framework/substantive - partial (Multiple issues) Conflict nature Inter-group Peace process 140: Kenya Local Agreements Parties On behalf of Mandera County:vHussein Mohamed ADAN, Abdi Wili ABDULLAHI, Abdille Sheikh BILLOW On behalf of Wajir County: Ali Abdi OGLE, Abdisalan Ibrahim ALI, Bishar Ali OLOW, On behalf of Garissa County: Dagane Karur OMAR, Hassan Abdi HURE, Hussein Noor Abdi On behalf of Tana River County: Kahonzi Esther JARHA, Ijema Godana HASSAN, Aden Ibrahim ARALE On behalf of Marsabit County: Guyo Karayu DIKA, Hassan Lolterka LENAROKI, Boru Arero BORU, On behalf of Sabburu County: Jason LESHOOMO, Peter P. LEKISAT, Benedicto L. LOLOSOLI On behalf of Meru County: Linos Kathera M. ERIMBA, Mitabathi M.KIRIMANA KIRIMANA On behalf of Nairobi County: Lucy Nyambura NDIRANGU, John Charles ODHIAMBO Third parties On behalf of North Eastern Province: Mr. James Ole Serian, EBS On behalf of Coast Province: Mr. Ernest G. Munyi, EBS On behalf of Eastern Province: Ms. Clare A. Omolo, EBS On behalf of Rift Valley Province: Mr. Osman Warfa, EBS Description County and regional leaders agree to measures to reduce conflict over theft of livestock, as well as provisions to stop unauthorised migration. Agreement document KE_110408_Modogashe Declaration (III).pdf [] Local agreement properties Process type Formal structured process Explain rationale It builds upon the Modogashe I and II declarations and it was supported by the government in a context in which there was already a national support mechanism for local initiatives. -

Al-Shabaab and Political Volatility in Kenya

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IDS OpenDocs EVIDENCE REPORT No 130 IDSAddressing and Mitigating Violence Tangled Ties: Al-Shabaab and Political Volatility in Kenya Jeremy Lind, Patrick Mutahi and Marjoke Oosterom April 2015 The IDS programme on Strengthening Evidence-based Policy works across seven key themes. Each theme works with partner institutions to co-construct policy-relevant knowledge and engage in policy-influencing processes. This material has been developed under the Addressing and Mitigating Violence theme. The material has been funded by UK aid from the UK Government, however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies. AG Level 2 Output ID: 74 TANGLED TIES: AL-SHABAAB AND POLITICAL VOLATILITY IN KENYA Jeremy Lind, Patrick Mutahi and Marjoke Oosterom April 2015 This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are clearly credited. First published by the Institute of Development Studies in April 2015 © Institute of Development Studies 2015 IDS is a charitable company limited by guarantee and registered in England (No. 877338). Contents Abbreviations 2 Acknowledgements 3 Executive summary 4 1 Introduction 6 2 Seeing like a state: review of Kenya’s relations with Somalia and its Somali population 8 2.1 The North Eastern Province 8 2.2 Eastleigh 10 2.3 -

Mandera County's 2010- 2030 Population Projections and Their Implications on Human Resources for Health

UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI POPULATION STUDIES AND RESEARCH INSTITUTE MANDERA COUNTY’S 2010- 2030 POPULATION PROJECTIONS AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS ON HUMAN RESOURCES FOR HEALTH MUNGAI KELVIN GATUHA Q50/81825/2015 A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN POPULATION STUDIES AT THE POPULATION STUDIES AND RESEARCH INSTITUTE, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI NOVEMBER, 2019 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this research project is my original work, and that to the best of my knowledge, it has not been presented in this or any other university for an academic degree award. Signature Date …………………………………....... ………………………………….. MUNGAI KELVIN GATUHA Q50/81825/2015 This project has been submitted for examination with our approval as university supervisors. 1. Signature Date ……………………………… ..……………………………… Dr. BONIFACE O. K’OYUGI Population Studies and Research Institute University of Nairobi 2. Signature Date ……………………………… ..……………………………… Dr. GEORGE ODIPO Population Studies and Research Institute University of Nairobi ii DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my entire family without whom, I would not have come this far. Special mention to my mother (Nyakio), father (Mungai) and siblings Paul, Njeri, Ciku, Shiru, and Ngugi who have always supported me in my quest for education. You all made this journey worthwhile and made sure I never lacked. Thank you all for the moral support and understanding during my time in school. May God bless you all abundantly! iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am grateful to God, the Most Beneficent and The Most Merciful, for having enabled me to study and reach this point of my education life. Without Him, I would not have made it this far.