1 Pastor Marc Wilson for Disorienting Times May 2020 a PLEA FOR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

HOPE in the WORD Is a Plan for You to Connect with God by Being in YOUR Bible for 90 Days

HOPE IN THE WORD is a plan for you to connect with God by being in YOUR bible for 90 days. The format will be Facebook Live from Monday to Thursday @ 10am and will allow you the flexibility to listen in/read at your own pace. In this custom plan, we will read ~ 33% of the Bible, from Old Testament accounts to all the Psalms, Proverbs, the gospel of Mark, and several of the New Testament epistles including Romans, Philippians, and others. Join us for 90 days of being fed with the Word of God! DAY DATE READING DONE 1 Jan 4, 2021 Mark 1-3; Proverbs 1 2 Jan 5, 2021 Mark 4-5; Psalm 1-2 3 Jan 6, 2021 Mark 6-7; Psalm 3-4; Romans 1 4 Jan 7, 2021 Mark 8-9; Psalm 4-5 5 Jan 11, 2021 Mark 10-12; Romans 2 6 Jan 12, 2021 Mark 13-14; Proverbs 2 7 Jan 13, 2021 Mark 15-16; Psalm 6-7; Romans 3 8 Jan 14, 2021 Genesis 1-2; Psalm 8-9 9 Jan 18, 2021 Genesis 3-4; Romans 4 10 Jan 19, 2021 Genesis 6-8; Psalm 10-11 11 Jan 20, 2021 Genesis 7-9; Psalm 12 12 Jan 21, 2021 Genesis 11-12; Romans 5 13 Jan 25, 2021 Genesis 13-14; Psalm 13-15 14 Jan 26, 2021 Genesis 15-17; Romans 6 15 Jan 27, 2021 Genesis 18-19; Psalm 16-17 16 Jan 28, 2021 Genesis 20-21; Romans 7 17 Feb 1, 2021 Genesis 22; Psalm 18-19; Proverbs 3-4 18 Feb 2, 2021 Genesis 23-24; Psalm 20 19 Feb 3, 2021 Genesis 25-26; Proverbs 5; Romans 8 20 Feb 4, 2021 Genesis 27-28; Psalm 21-22 21 Feb 8, 2021 Genesis 29-30; Psalm 23-25 22 Feb 9 2021 Genesis 31-32; Proverbs 6 23 Feb 10, 2021 Genesis 33-34; Romans 9-10 24 Feb 11, 2021 Genesis 35,37; Romans 11 25 Feb 15, 2021 Genesis 38-39; Psalm 26-28 26 Feb 16, 2021 Genesis -

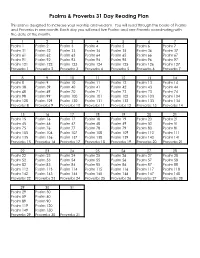

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

Week 95. Psalms

Psalms Part 8 Syllabus Featured Week Psalm Type of Psalm Teacher 1 137 Imprecatory Psalms General Introduction 2 1 Introduction to Psalms Mike Mazzalongo 3 15 Wisdom Psalms Mike Mazzalongo 4 19 Nature Psalms Mike Mazzalongo 5 146 Praise Psalms Christopher Ash 6 74 Psalms of Lament Christopher Ash 7 130 Songs of Ascent Alistair Begg Part 1 Psalm 137 “In Psalms, it talks about God basically celebrating taking babies and smashing their heads against the rocks.” Bob Seidensticker, 2007 Psalm 137 1 By the rivers of Babylon we sit down and weep when we remember Zion. 2 On the poplars in her midst we hang our harps, 3 for there our captors ask us to compose songs; those who mock us demand that we be happy, saying: “Sing for us a song about Zion!” 4 How can we sing a song to the Lord in a foreign land? 5 If I forget you, O Jerusalem, may my right hand be crippled! 6 May my tongue stick to the roof of my mouth, if I do not remember you, and do not give Jerusalem priority over whatever gives me the most joy. 7 Remember, O Lord, what the Edomites did on the day Jerusalem fell. They said, “Tear it down, tear it down, right to its very foundation!” 8 O daughter Babylon, soon to be devastated! How blessed will be the one who repays you for what you dished out to us! 9 How blessed will be the one who grabs your babies and smashes them on a rock! In light of the recent execution of 21 Christians and capture of hundreds more in Syria, perhaps it’s time to ask, “Should we be praying the imprecatory psalms against ISIS?” Written in the theocratic context of Israel, when God himself had a throne on earth, these psalms (e.g., Ps. -

Commentary on Psalms - Volume 3

Commentary on Psalms - Volume 3 Author(s): Calvin, John (1509-1564) Calvin, Jean (1509-1564) (Alternative) (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Calvin found Psalms to be one of the richest books in the Bible. As he writes in the introduction, "there is no other book in which we are more perfectly taught the right manner of praising God, or in which we are more powerfully stirred up to the performance of this religious exercise." This comment- ary--the last Calvin wrote--clearly expressed Calvin©s deep love for this book. Calvin©s Commentary on Psalms is thus one of his best commentaries, and one can greatly profit from reading even a portion of it. Tim Perrine CCEL Staff Writer This volume contains Calvin©s commentary on chapters 67 through 92. Subjects: The Bible Works about the Bible i Contents Commentary on Psalms 67-92 1 Psalm 67 2 Psalm 67:1-7 3 Psalm 68 5 Psalm 68:1-6 6 Psalm 68:7-10 11 Psalm 68:11-14 14 Psalm 68:15-17 19 Psalm 68:18-24 23 Psalm 68:25-27 29 Psalm 68:28-30 33 Psalm 68:31-35 37 Psalm 69 40 Psalm 69:1-5 41 Psalm 69:6-9 46 Psalm 69:10-13 50 Psalm 69:14-18 54 Psalm 69:19-21 56 Psalm 69:22-29 59 Psalm 69:30-33 66 Psalm 69:34-36 68 Psalm 70 70 Psalm 70:1-5 71 Psalm 71 72 Psalm 71:1-4 73 Psalm 71:5-8 75 ii Psalm 71:9-13 78 Psalm 71:14-16 80 Psalm 71:17-19 84 Psalm 71:20-24 86 Psalm 72 88 Psalm 72:1-6 90 Psalm 72:7-11 96 Psalm 72:12-15 99 Psalm 72:16-20 101 Psalm 73 105 Psalm 73:1-3 106 Psalm 73:4-9 111 Psalm 73:10-14 117 Psalm 73:15-17 122 Psalm 73:18-20 126 Psalm 73:21-24 -

Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures Steven Dunn Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures Steven Dunn Marquette University Recommended Citation Dunn, Steven, "Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures" (2009). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 13. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/13 Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures By Steven Dunn, B.A., M.Div. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin December 2009 ABSTRACT Wisdom Editing in the Book of Psalms: Vocabulary, Themes, and Structures Steven Dunn, B.A., M.Div. Marquette University, 2009 This study examines the pervasive influence of post-exilic wisdom editors and writers in the shaping of the Psalter by analyzing the use of wisdom elements—vocabulary, themes, rhetorical devices, and parallels with other Ancient Near Eastern wisdom traditions. I begin with an analysis and critique of the most prominent authors on the subject of wisdom in the Psalter, and expand upon previous research as I propose that evidence of wisdom influence is found in psalm titles, the structure of the Psalter, and among the various genres of psalms. I find further evidence of wisdom influence in creation theology, as seen in Psalms 19, 33, 104, and 148, for which parallels are found in other A.N.E. wisdom texts. In essence, in its final form, the entire Psalter reveals the work of scribes and teachers associated with post-exilic wisdom traditions or schools associated with the temple. -

Psalm 74-77 73-83 Psalms of Asaph Or Family Members

Psalm 74-77 73-83 Psalms of Asaph or family members – LT Psalm 71-73 – 71 Psalm of Trust; 72 First Psalm of Solomon; 73 A Psalm of God’s Goodness (1st of the BOOK THREE and 2nd of Asaph (13 total)) Asaph was a Levite Worship Leader mentioned in 2 Kings 18 and 1 & 2 Chronicles Psalm 74 (A Plea for God’s Judgment) –A Contemplation or Maschil (used 13X) of Asaph, or, "A Psalm of Asaph, to give instruction." A time of great national oppression, after Shishak attacks Judah (1 King 14:25) 926 BC or after captivity by Nebuchadnezzar (2 Kings 24) 587 BC God is faithful - Looks at the present condition, refers back to the past (and God’s faithfulness) and looks out to the future of God’s remedy. Similar to Habakkuk 3 Prayers Vv1-3 – “sheep” Prayer 1 - Supplication 1. “Why” have you allowed this – “cast us off forever” not possible 2. “Remember” - “congregation”/“tribe of Your inheritance” “purchased”/“redeemed” – As if God can “forget” 3. “Lift up Your feet” – a plea for God to “return” 4. “Just because you can't see or imagine a good reason why God might allow something to happen it does not mean there can't be one.” – Tim Keller – God is always in control 5. Current times Vv4-9 “Your enemies” and “They” (6X) 1. Destruction, defilement, disaster, desolation 2. The enemies of God will always try to attack the people of God by natural means a. But we fight a “supernatural” battle – Eph. 6:12-13 Vv10-11 – 3 Questions “How long” and “Why” don’t you used your “Right hand”Prayer 2 – Supplication/Entreaty Vv12-17 – Remembering the past of God’s faithfulness – God then “You” 7X 1. -

Fr. Lazarus Moore the Septuagint Psalms in English

THE PSALTER Second printing Revised PRINTED IN INDIA AT THE DIOCESAN PRESS, MADRAS — 1971. (First edition, 1966) (Translated by Archimandrite Lazarus Moore) INDEX OF TITLES Psalm The Two Ways: Tree or Dust .......................................................................................... 1 The Messianic Drama: Warnings to Rulers and Nations ........................................... 2 A Psalm of David; when he fled from His Son Absalom ........................................... 3 An Evening Prayer of Trust in God............................................................................... 4 A Morning Prayer for Guidance .................................................................................... 5 A Cry in Anguish of Body and Soul.............................................................................. 6 God the Just Judge Strong and Patient.......................................................................... 7 The Greatness of God and His Love for Men............................................................... 8 Call to Make God Known to the Nations ..................................................................... 9 An Act of Trust ............................................................................................................... 10 The Safety of the Poor and Needy ............................................................................... 11 My Heart Rejoices in Thy Salvation ............................................................................ 12 Unbelief Leads to Universal -

Genres-Of-The-Psalms.Pdf

British Bible School – Online Classes: 14th September 2020 – 30th November 2020 THE PSALMS THE GENRES OF THE PSALMS 1. Genre is a word we use to identify certain types or categories of things which have the same characteristics within a wider or more general classification. Books, music, films all have their own genres. Books: Fiction – crime, sci-fi, fantasy, romance; and Non-fiction - history, biography, travel, science. Music – classical, pop, heavy metal, rap, soul. Films – comedy, westerns, period dramas, horror, war, documentary, animation. If we know what the genre is then we have a certain expectation or understanding of what we shall experience when we read the book, listen to the music, or watch the film. Just as we can identify genres in these other areas, so the Bible is a book which contains many different types or genres of literature: e.g. history, letters, law codes, prophecy, apocalyptic, wisdom and poetry. To correctly understand what we are reading we need to identify the genre. All the Psalms are in the genre of poetry. But within the genre of poetry we can identify seven different genres or types of Psalms. The psalms within each group display certain similar characteristics, phrases, and structure. The two primary genres of the Psalms are: i) Hymns ii) Laments Other genres are: iii) Psalms of thanksgiving iv) Psalms of remembrance v) Psalms of confidence vi) Wisdom psalms vii) Kingship or royal psalms This list is taken from Tremper Longman III, How to Read the Psalms, IVP, 1988. Other writers may use slightly different categories. Identifying the genre will help our understanding and interpretation of the text we are studying. -

WEEK 85, DAY 1 PSALMS 74, 77, 79, and 80 Good Morning. This Is

WEEK 85, DAY 1 PSALMS 74, 77, 79, and 80 Good morning. This is Pastor Soper and welcome to Week 85 of Know the Word. May I encourage you by saying that we are now less than six weeks away from finishing Know the Word? Then you will be able to say that you have carefully and prayerfully read the entire Bible, from cover to cover! That will, I believe, turn out to be one of the greatest and most beneficial accomplishments of your entire Christian life! I can honestly tell you that producing these recordings has been one of the greatest and most blessed accomplishments of my life as a Christian! Well, today we read Psalms 74, 77, 79 and 80. These Psalms are all found in Book 3 of the Psalter. (You will remember that Book 2 ended with the expression at the end of Psalm 72: “This concludes the prayers of David, son of Jesse,” even though several more Psalms bearing his name will be found mostly in Books 4 and 5). We also learned that there are five Books of Psalms, which appear to roughly correspond to the five Books of Moses. I have to confess to you, however, that the division between the five books have always seemed a bit arbitrary to me and I found myself wondering about that again this week. It is true, as some scholars have noted, the Psalms in Book 1 frequently use the name “Jehovah” or “Lord,” while the second Book seems to highlight the name “Elohim” or “God.” It is also apparent, as you may have quickly noticed this morning, that most of the Psalms in Book 3 show some evidence of being “exilic,” that is, they were written after the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians. -

The Rhetorical Use of Creation Imagery in Psalm 74 Graham J. L

STR 10.2 (Fall 2019): 5–29 6 SOUTHEASTERN THEOLOGICAL REVIEW of “why?” and “how long?” (vv. 10–11) and includes several pleas for God’s intervention (vv. 18–23). Yet, in the midst of this psalm is the re markable declaration of God’s works of salvation from of old (vv. 12– 17), in which he defeats the chaotic forces and sets up the created order. 1 Undoubtedly, such vivid imagery is able to evoke a wide array of texts, images, and events, which has generated much scholarly debate regarding the nature, origin, and use of creation imagery. However, for the psalmist the use of this creation imagery primarily functions as a crucial compo St. David’s School, Raleigh, NC nent of this desperate plea for God to respond and to act. The poetic use of such imagery, in the words of T. S. Eliot, is a “raid on the inarticulate,”3 This article explores the rhetorical function of creation imagery and how it is utilized a powerful and expressive articulation of the psalmist’s faith in God’s con particularly in the communal lament of Ps 74. Although “creation” is often defined trol over the cosmos and the forces that threaten it. This essay will thus exclusively in terms of origination, it is a much more expansive and complex theological explore the nature of creation imagery in Ps 74, and how it is used rhe category that includes God’s ongoing interaction with his creation. The biblical authors torically as a plea for God to bring about his works of salvation in the thus draw images and language from creation for a variety of rhetorical purposes and present as he did of old. -

THE TRIBULATION PSALM with Verse References

THE TRIBULATION PSALM With Verse References DAY ONE 1) Psalm 8:1 O Lord, our Lord, How excellent is Your name in all the earth, Who have set Your glory above the heavens! 2) Psalm 97:9 For You, Lord, are most high above all the earth; You are exalted far above all gods. 3) Psalm 89:11 The heavens are Yours, the earth also is Yours; The world and all its fullness, You have founded them. 4) Psalm 102:25 Of old You laid the foundation of the earth, And the heavens are the work of Your hands. DAY TWO 5) Psalm 77:11 I will remember the works of the Lord; Surely I will remember Your wonders of old. 6) Psalm 93:2 Your throne is established from of old; You are from everlasting. 7) Psalm 75:1 We give thanks to You, O God, we give thanks! For Your wondrous works declare that Your name is near. 8) Psalm 48:10 According to Your name, O God, So is Your praise to the ends of the earth; Your right hand is full of righteousness. DAY THREE 9) Psalm 92:1-2 It is good to give thanks to the Lord, And to sing praises to Your name, O Most High; To declare Your lovingkindness in the morning, And Your faithfulness every night. 10) Psalm 143:8 Cause me to hear Your lovingkindness in the morning, For in You do I trust; Cause me to know the way in which I should walk, For I lift up my soul to You.