Perceptions of Phoenician Identity and Material Culture As Reflected in Museum Records and Displays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TELL ES-SULTAN 2015 a Pilot Project for Archaeology in Palestine

TELL ES-SULTAN 2015 A Pilot Project for Archaeology in Palestine Tell es-Sultan, the eastern flank of Spring Hill. In the foreground is the restored Early Bronze Age III (2700–2350 B.C.E.) Palace G. In the background is the Spring of 'Ain es-Sultan. Photograph by Lorenzo Nigro, © University of Rome “La Sapienza” ROSAPAJ. Lorenzo Nigro he eleventh season (April–June 2015) of the archaeological The Italian-Palestinian Pilot Project and the investigation and site protection as well as valoriza- Cultural Heritage of Palestine tion of the site of Tell es-Sultan was carried out by the In 1997 the University of Rome “La Sapienza” was cho- TUniversity of Rome “La Sapienza” (under the direction of the sen to partner with the Department of Archaeology and present writer) and the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism and Cultural Heritage of the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities Antiquities – Department of Archaeology and Cultural Heritage of Palestine (MoTA-DACH) on a joint project to restore (directed by Jehad Yasine) with the aims to: (1) re-examine the site of Tell es-Sultan as a field school for young Italian several of the historical archaeological highlights of this long- and Palestinian archaeologists and a tourist attraction. The standing site and (2) make the site accessible and appealing to site had been neglected for almost 40 years, since Kathleen the public through restorations and a large set of illustrative and M. Kenyon’s last season there in 1958. The joint Italian- explanatory devices set up with the help of the Italian Ministry Palestinian Jericho Expedition inaugurated a new model of of Foreign Affairs and the Jericho Municipality, and to make the archaeological cooperation. -

AZIENDA SANITARIA LOCALE N Olbia

SERVIIZIIO SANIITARIIO REGIIONE AUTONOMA DELLA SARDEGNA AZIENDA SANITARIA LOCALE N°2 Olbia GRADUATORIA “ALLEGATO B” ALLA DELIBERAZIONE DEL DIRETTORE GENERALE N°1553 DEL 21.06.2011 N° COGNOME NOME LUOGO DI NASCITA DATA DI NASCITA PUNTEGGIO NOTE 1 SOTGIU ANDREA SASSARI 08/06/1951 8,910 2 LEON SUAREZ ANA VERONICA LAS PALMAS DE GRAN CANARIA 25/11/1970 5,360 3 GIORDANO ORSINI EUGENIO TORRE DEL GRECO 22/12/1982 4,172 4 TOSI ELIANE CURITIBA 20/07/1966 2,906 5 DI PASQUALE LUCA ISERNIA 13/05/1983 2,589 6 BIOSA ANTONIO LA MADDALENA 17/01/1964 2,520 7 BARONE RAFFAELE GELA 29/03/1986 2,460 8 PITZALIS VALERIA CAGLIARI 22/06/1978 2,369 9 GAETANI MARIANNA FOGGIA 13/04/1983 2,320 10 ISU ALESSANDRO SAN GAVINO MONREALE 05/02/1974 2,270 11 SERAFINI VINCENZO ASCOLI PICENO 19/03/1977 2,240 12 TALANA MICHELE IGLESIAS 21/06/1987 1,780 p. per età 13 MELIS MIRKO CAGLIARI 06/11/1986 1,780 14 ABBRUSCATO RICCARDO AGRIGENTO 14/12/1981 1,660 15 PODDA SILVIA ARBUS 10/07/1985 1,642 1 Pubblica selezione - Collaboratore Professionale Sanitario-Tecnico Sanitario di Radiologia Medica – cat. D. 16 LODATO NICOLA CAVA DE' TIRRENI 15/05/1982 1,570 p. per età 17 DE DOMINICIS GIANLUCA ARIANO IRPINO 14/02/1977 1,570 18 DI CAIRANO LUCA PASCAL LUGANO 15/08/1981 1,550 19 LIOCE SABRINA SAN SEVERO 06/10/1987 1,460 20 D'AMICO ALFONSO CAVA DE' TIRRENI 14/03/1981 0,990 21 CALABRO' FRANCESCA CAGLIARI 14/03/1985 0,961 22 CARBONE CARMINE AVELLINO 17/11/1975 0,947 23 RUNZA GIUSEPPE ROSOLINI 03/03/1977 0,920 24 MICILLO ALESSANDRO LATINA 02/04/1986 0,902 25 PLACENINO MIRELLA SAN GIOVANNI ROTONDO 12/04/1987 0,800 26 BIBBO' ANDREA BENEVENTO 15/09/1987 0,710 p. -

VOYAGE to VALLETTA from the ‘Eternal City’ to the ‘Silent City’ Aboard the Variety Voyager 16Th to 24Th May 2016

LAUNCH OFFER - SAVE £300 PER PERSON VOYAGE TO VALLETTA From the ‘Eternal City’ to the ‘Silent City’ aboard the Variety Voyager 16th to 24th May 2016 All special offers are subject to availability. Our current booking conditions apply to all reservations and are available on request. Cover image: View over the Greek Doric Temple, Segesta, Sicily NOBLE CALEDONIA ere is a rare opportunity to visit both Ruins of the Greek temple at Selinunte Sardinia and Sicily, the Mediterranean’s Htwo largest islands combined with time to explore some of Malta’s wonders from the comfort of the private yacht, the Variety Voyager. This is not an itinerary which a large cruise ship could operate but one which is ideal for our 72-passenger vessel. All three islands feature a magnificent array of ancient ruins and attractive towns and villages which we will visit during our guided excursions whilst we have also allowed for ample time to explore independently. With comfortable temperatures and relatively crowd free sites, May is the perfect time to discover these islands and in addition we have the added benefit of excellent local THE ITINERARY Day 1 London to Rome, Italy. ITALY guides along the way and a knowledgeable Fly by scheduled flight. Arrive Q this afternoon and transfer to the onboard guest speaker who will bring to life Isla Maddalena Rome Olbia• • Variety Voyager in Civitavecchia. • •Civitavecchia Enjoy a welcome drink and dinner all we see. SARDINIA as we sail this evening to Sardinia. TYRRHENIAN SEA Cagliari• Day 2 Isla Maddalena & Olbia, Piazza • Armerina Sardinia. In 1789 Napoleon, then Mazara del • Vallo SICILY a young artillery commander was •Gela thwarted in his attempt to take GOZOQ • •Valletta the Maddalena archipelago by MALTA local Sardinian forces and in 1803 Lord Nelson arrived. -

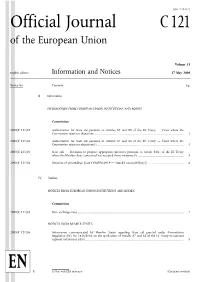

Official Journal C121

ISSN 1725-2423 Official Journal C 121 of the European Union Volume 51 English edition Information and Notices 17 May 2008 Notice No Contents Page II Information INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS AND BODIES Commission 2008/C 121/01 Authorisation for State aid pursuant to Articles 87 and 88 of the EC Treaty — Cases where the Commission raises no objections ............................................................................................. 1 2008/C 121/02 Authorisation for State aid pursuant to Articles 87 and 88 of the EC Treaty — Cases where the Commission raises no objections (1) .......................................................................................... 4 2008/C 121/03 State aids — Decisions to propose appropriate measures pursuant to Article 88(1) of the EC Treaty where the Member State concerned has accepted those measures (1) ................................................ 5 2008/C 121/04 Initiation of proceedings (Case COMP/M.4919 — Statoil/Conocophillips) (1) ..................................... 6 IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS AND BODIES Commission 2008/C 121/05 Euro exchange rates ............................................................................................................... 7 NOTICES FROM MEMBER STATES 2008/C 121/06 Information communicated by Member States regarding State aid granted under Commission Regulation (EC) No 1628/2006 on the application of Articles 87 and 88 of the EC Treaty to national regional investment aid (1) ...................................................................................................... -

Ml~;~An" a 1998 Penn Bowl 007

Ml~;~aN" A 1998 Penn Bowl 007 (SCIENCE - Biology) l. This group of marine organisms is usually characterized by a peduncle or stalk attached to the substrate and a calyx of feathery arms, but it also includes the free-swimming feather stars. For tenn points name this class of echinoderms commonly known as the sea lillies. (GEOGRAPHY - Physical) 2. Ascend the Khumbu Icefall, head east up the Western Cwm [KOOM] and climb the sheer but technically unchallenging Lhotse [LOT-SEE] Face. Now head up the SouthEast ridge to the South Col, the South Summit and the summit itself. After following these directions you will have climbed, for 10 points, what mountain, first conquered in 1953 by Tenzing and Hillary. ANSWER: Mount _EveresC OR _Cho-mo-Iung-ma_ (HISTORY - Ancient - Non-Western) 3. Believing that they should not mix with people they conquered, this nomadic group moved south from the Caucasus and gradually defeated the Harappa people. The Rig-Veda says that they expanded into the Punjab and the Ganges River basin. FTP, name this group whose traditions shaped Hinduism and the Indian caste system, and whose name comes from the Sanskrit for "noble." ANSWER: _Aryans_ (MYTHOLOGY - Norse) 4. According to legend, the gods killed the giant Aurgelmir, the first created being, and rolled his body into the central void of the universe thus creating this realm. His flesh became the land, his blood the oceans, his bones the mountains, and his hair the trees. This place is situated halfway between Niflheim on the north and Muspelheim to the south. FTP -- name this Middle Earth of Norse mythology. -

A Case Study of Third Millennium BC Early Urbanism in North-Central Jordan

Lorenzo Nigro Lorenzo Nigro Rome “La Sapienza” University Department of Historical, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences of Antiquity-Sec- tion Near East Via Palestro, 63, 00185 Rome e-mail: [email protected] Khirbat al-Batråwπ: a Case Study of third Millennium BC Early Urbanism in North-Central Jordan Premise 3- The levels and trajectories of interaction and The rise of urbanization in Transjordan during the exchange between communities and regions, third millennium BC, which was a development through the Jordan valley, Palestine, southern of the Early Bronze Age culture that emerged in Syria and the coastal Levant (Esse 1991). the region during the last centuries of the fourth 4- The physical remains of these early settlements, millennium BC (Kenyon 1957: 93-102; Esse 1989: in which meaningful public architecture – na- 82-85; Nigro 2005: 1-6, 109-110, 197-202, 2007a: mely, massive fortification works – first appear 36-38), is a distinct historic-archaeological pheno- (Kempinski 1992; Herzog 1997: 42-97; Nigro menon which has attracted the attention of scho- 2006b). There is general consensus that these lars aiming to produce a reliable definition of early fortifications, often referred to in the context urbanism, if indeed it existed, in this fringe area of “walled towns” or “fortified settlements” of the Levant. After coping with terminological is- (Schaub 1982; Schaub and Chesson 2007), are sues, derived mainly from the fact that ‘urbanism’ the most meaningful witnesses of early southern in this region of the ancient -

The Temple of Astarte “Aglaia” at Motya and Its Cultural Significance in the Mediterranean Realm

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342170872 The Temple of Astarte "Aglaia" at Motya and Its Cultural Significance in the Mediterranean Realm Article · January 2019 CITATIONS READS 0 329 1 author: Lorenzo Nigro Sapienza University of Rome 255 PUBLICATIONS 731 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: microbiology helps archeology View project PeMSea [PRIN2017] - Peoples of the Middle Sea. Innovation and Integration in Ancient Mediterranean (1600-500 BC) View project All content following this page was uploaded by Lorenzo Nigro on 15 June 2020. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Chapter 5 Lorenzo Nigro The Temple of Astarte “Aglaia” at Motya and Its Cultural Significance in the Mediterranean Realm Abstract: Recent excavations at Motya by the Sapienza University of Rome and the Sicil- ian Superintendence of Trapani have expanded our information on the Phoenician goddess Astarte, her sacred places, and her role in the Phoenician expansion to the West during the first half of the first millennium BCE. Two previously unknown religious buildings dedicated to this deity have been discovered and excavated in the last decade. The present article discusses the oldest temple dedicated to the goddess, located in the Sacred Area of the Kothon in southwestern quadrant of the island (Zone C). The indigenous population worshipped a major goddess at the time of Phoenician arrival, so that the cult of Astarte was easily assimilated and transformed into a shared religious complex. Here, the finds that connect Astarte of Motya with her Mediterranean parallels are surveyed. -

The Burial of the Urban Poor in Italy in the Late Republic and Early Empire

Death, disposal and the destitute: The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Republic and early Empire Emma-Jayne Graham Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology University of Sheffield December 2004 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk The following have been excluded from this digital copy at the request of the university: Fig 12 on page 24 Fig 16 on page 61 Fig 24 on page 162 Fig 25 on page 163 Fig 26 on page 164 Fig 28 on page 168 Fig 30on page 170 Fig 31 on page 173 Abstract Recent studies of Roman funerary practices have demonstrated that these activities were a vital component of urban social and religious processes. These investigations have, however, largely privileged the importance of these activities to the upper levels of society. Attempts to examine the responses of the lower classes to death, and its consequent demands for disposal and commemoration, have focused on the activities of freedmen and slaves anxious to establish or maintain their social position. The free poor, living on the edge of subsistence, are often disregarded and believed to have been unceremoniously discarded within anonymous mass graves (puticuli) such as those discovered at Rome by Lanciani in the late nineteenth century. This thesis re-examines the archaeological and historical evidence for the funerary practices of the urban poor in Italy within their appropriate social, legal and religious context. The thesis attempts to demonstrate that the desire for commemoration and the need to provide legitimate burial were strong at all social levels and linked to several factors common to all social strata. -

The Epigraphy of the Tophet

ISSN 2239-5393 The Epigraphy of the Tophet Maria Giulia Amadasi Guzzo – José Ángel Zamora López (Sapienza Università di Roma – CSIC, Madrid) Abstract The present contribution reassesses the main aspects of the epigraphic sources found in the so-called tophet in order to demonstrate how they are significant and how they undermine the funerary interpretations of these precincts. The inscriptions decisively define the tophet as a place of worship, a sanctuary where sacrifices were made to specific deities in specific rites. The epigraphic evidence combined with literary and archaeological data show how these sacrifices consisted of infants and small animals (either as substitutes or interred together), sometimes commemorated by the inscriptions themselves. Keywords History of Religions, Child Sacrifice, Northwest Semitic Epigraphy, Mediterranean History, Phoenician & Punic World. 1. Introduction Our basic knowledge of the special type of Phoenician and Punic sanctuaries called tophet (a conventional term taken from the Hebrew Bible) seems to be based on wide variety of sources that can be combined to provide an overall interpretation. In fact, archaeological research now provides us with relatively substantial knowledge of the geographical and chronological distribution of these sacred sites and of their structure. Present in some central Mediterranean Phoenician settlements (including on Sardinia) from their foundation, or shortly after, they persist and multiply in North Africa at a later period, generally after the destruction of Carthage1. Archaeology, also, enables us to formulate a “material” definition of these places: they are always– essentially – open-air sites constantly located on the margins of towns, where pottery containers are buried in which the burnt remains of babies and/or baby Received: 11.09.2013. -

4. Film As Basis for Poster Examination

University of Lapland, Faculty of Art and Design Title of the pro gradu thesis: Translating K-Horror to the West: The Difference in Film Poster Design For South Koreans and an International Audience Author: Meri Aisala Degree program: Graphic Design Type of the work: Pro Gradu master’s thesis Number of pages: 65 Year of publication: 2018 Cover art & layout: Meri Aisala Summary For my pro gradu master’s degree, I conducted research on the topic of South Korean horror film posters. The central question of my research is: “How do the visual features of South Korean horror film posters change when they are reconstructed for an international audience?” I compare examples of original Korean horror movie posters to English language versions constructed for an international audience through a mostly American lens. My study method is semiotics and close reading. Korean horror posters have their own, unique style that emphasizes emotion and interpersonal relationships. International versions of the posters are geared toward an audience from a different visual culture and the poster designs get translated accordingly, but they still maintain aspects of Korean visual style. Keywords: K-Horror, melodrama, genre, subgenre, semiotics, poster I give a permission the pro gradu thesis to be read in the Library. 2 목차Contents Summary 2 1. Introduction 4 1.1 Research problem and goals 4 1.2 The movie poster 6 1.3 The special features of K-Horror 7 1.3.1 Defining the horror genre 7 1.3.2 The subgenres of K-Horror 8 1.3.3 Melodrama 9 2. Study methods and material 12 2.1 Semiotics 12 2.2 Close reading 18 2.3 Differences in visual culture - South Korea and the West 19 3. -

The Origins of the Kouros

THE ORIGINS OF THE KOUROS By REBECCA ANN DUNHAM A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2005 Copyright 2005 by Rebecca Ann Dunham This document is dedicated to my mom. TABLE OF CONTENTS page LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... vi ABSTRACT.........................................................................................................................x CHAPTER 1 DEFINITION OF THE KOUROS TYPE ....................................................................1 Pose...............................................................................................................................2 Size and material...........................................................................................................2 Nudity ...........................................................................................................................3 Body Shape and Treatment of Musculature .................................................................3 Execution ......................................................................................................................4 Function ........................................................................................................................5 Provenances ..................................................................................................................7 -

Harvard Fall Tournament XIII Edited by Jon Suh with Assistance From

Harvard Fall Tournament XIII Edited by Jon Suh with assistance from Raynor Kuang, Jakob Myers, and Michael Yue Questions by Jon Suh, Michael Yue, Ricky Li, Kelvin Li, Robert Chu, Alex Cohen, Kevin Huang, Justin Duffy, Raynor Kuang, Chloe Levine, Jakob Myers, Thomas Gioia, Erik Owen, Michael Horton, Luke Minton, Olivia Murton, Conrad Oberhaus, Jiho Park, Alice Sayphraraj, Patrick Magee, and Eric Mukherjee Special thanks to Will Alston, Jordan Brownstein, Robert Chu, Stephen Eltinge, and Olivia Murton Round 3 Tossups 1. France banned this good in 1748 under the belief that it caused leprosy, a measure that was overturned through the efforts of Antoine Parmentier [“par-MEN-tee-ay”]. Frederick the Great was known as the “king” of this good for encouraging its cultivation. This good gives the alternate name of the War of the Bavarian Succession. The (*) “Lumper” variety of this good suffered a disaster that caused many people to practice “souperism” or flee in vessels known as “coffin ships.” A blight of this good decreased the population of a European nation by 25%. For 10 points, name this foodstuff that suffered the Great Famine of the 1840s in Ireland. ANSWER: potatoes <Suh> 2. An actress was able to commit to this show after the cancellation of the sitcom Muddling Through. A “shag” worn by a character on this show’s second season is one of the most copied women’s hairstyles of all time. Characters on this show often observe an “Ugly Naked Guy.” A character on this show is called a (*) “lobster” by a woman who wrote the song “Smelly Cat.” A character on this show continually justifies his infidelity by saying “We were on a break!” For 10 points, name this television series with the theme song “I’ll be There for You” about six companions, including Ross and Rachel, who often hang out at the Central Perk cafe in New York City.