Enhancing Healthcare Decision-Making Process: Findings from Orthopaedic Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scientific Programme for All

Optimal radiotherapy Scientific Programme for all ESTRO ANNUAL CONFE RENCE 27 - 31 August 2021 Onsite in Madrid, Spain & Online Saturday 28 August 2021 Track: Radiobiology Teaching lecture: The microbiome: Its role in cancer development and treatment response Saturday, 28 August 2021 08:00 - 08:40 N104 Chair: Marc Vooijs - 08:00 The microbiome: Its role in cancer development and treatment response SP - 0004 A. Facciabene (USA) Track: Clinical Teaching lecture: Breast reconstruction and radiotherapy Saturday, 28 August 2021 08:00 - 08:40 Plenary Chair: Philip Poortmans - 08:00 Breast reconstruction and radiotherapy SP - 0005 O. Kaidar-Person (Israel) Track: Clinical Teaching lecture: Neurocognitive changes following radiotherapy for primary brain tumours Saturday, 28 August 2021 08:00 - 08:40 Room 1 Chair: Brigitta G. Baumert - 08:00 Evaluation and care of neurocognitive effects after radiotherapy SP - 0006 M. Klein (The Netherlands) 08:20 Imaging biomarkers of dose-induced damage to critical memory regions SP - 0007 A. Laprie (France Track: Physics Teaching lecture: Independent dose calculation and pre-treatment patient specific QA Saturday, 28 August 2021 08:00 - 08:40 Room 2.1 Chair: Kari Tanderup - 08:00 Independent dose calculation and pre-treatment patient specific QA SP - 0008 P. Carrasco de Fez (Spain) 1 Track: Physics Teaching lecture: Diffusion MRI: How to get started Saturday, 28 August 2021 08:00 - 08:40 Room 2.2 Chair: Tufve Nyholm - Chair: Jan Lagendijk - 08:00 Diffusion MRI: How to get started SP - 0009 R. Tijssen (The Netherlands) Track: RTT Teaching lecture: The role of RTT leadership in advancing multi-disciplinary research Saturday, 28 August 2021 08:00 - 08:40 N103 Chair: Sophie Perryck - 08:00 The role of RTT leadership in advancing multi-disciplinary research SP - 0010 M. -

Champaign | Fall 2012 Dean's List | Illinois, out of State, International Students

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign | Fall 2012 Dean's List | Illinois, Out of State, International Students STATE / ZIP MIDDLE STUDENT NATION CITY CODE FIRST NAME NAME LAST NAME CLASS COLLEGE MAJOR Illinois Students Agricultural, Consumer & IL Addison Sarah Elizabeth Adams 4 Environmental Sciences Animal Sciences IL Addison Kimberly A Arquines 3 Liberal Arts & Sciences Sociology IL Addison Alex Baciu 1 Liberal Arts & Sciences Chemical Engineering IL Addison Justin T Cruce 2 Engineering Civil Engineering IL Addison Christopher M Gerth 3 Engineering Electrical Engineering IL Addison Cheryl A Kamide 1 Division of General Studies Undeclared IL Addison Timothy P O'Connor 2 Liberal Arts & Sciences Political Science IL Addison Megh J Patel 2 Liberal Arts & Sciences Molecular and Cellular Biology IL Addison Jennifer Marie Rowley 3 Liberal Arts & Sciences English IL Addison Justin T Sumait 1 Division of General Studies Undeclared IL Algonquin Melissa Kelly Blunk 4 Applied Health Sciences Recreation, Sport, and Tourism IL Algonquin Connor Lawrence Booker 1 Liberal Arts & Sciences Biology IL Algonquin Nicholas P Demetriou 2 Engineering Materials Science & Engineering IL Algonquin Anthony J Dombrowski 4 Fine & Applied Arts Architectural Studies IL Algonquin Jessica Ann Gardeck 3 Liberal Arts & Sciences Communication IL Algonquin Jason Mark Gatz 3 Applied Health Sciences Recreation, Sport, and Tourism IL Algonquin Carol Ann Henning 4 Liberal Arts & Sciences Psychology IL Algonquin Michael E Hubner 1 Engineering Mechanical Engineering IL Algonquin -

2003 Directory of State and Local Government

DIRECTORY OF STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT Prepared by RESEARCH DIVISION LEGISLATIVE COUNSEL BUREAU January 2003 Revised October 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Please refer to the Alphabetical Index to the Directory of State and Local Gov- ernment for a complete list of agencies. NEVADA STATE GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATION CHART .................D-9 CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATION .................................................. D-11 DIRECTORY OF STATE GOVERNMENT CONSTITUTIONAL OFFICERS: Attorney General ....................................................................... D-13 State Controller ......................................................................... D-17 Governor ................................................................................. D-18 Lieutenant Governor ................................................................... D-21 Secretary of State ....................................................................... D-22 State Treasurer .......................................................................... D-23 EXECUTIVE BOARDS ................................................................. D-24 UNIVERSITY AND COMMUNITY COLLEGE SYSTEM OF NEVADA .... D-25 EXECUTIVE BRANCH AGENCIES: Department of Administration ........................................................ D-30 Administrative Services Division ............................................... D-30 Budget Division .................................................................... D-30 Economic Forum ................................................................. -

9Th International Bearded Vulture Observation Days

9 th International Bearded Vulture Observation Days October 11th 2014 (period: 11th-19th of October) Dominique Waldvogel and Richard Zink A cooperation within the International Bearded vulture Monitoring (IBM) The project partners: Nationalpark Hohe Tauern LPO Grands Causses Parc Nationale du Mercantour Parco Naturale Alpi Marittime Parc National les Ecrins Parc National de la Vanoise Parc Naturel regional du Vercors Regione Autonoma Valle d’Aosta & Parco Nazionale Gran Paradiso A.S.T.E.R.S. (Conservatoire des l’espaces naturels Haute-Savoie) Provincia di Sondrio, Ufficio Faunistico Parco Nazionale dello Stelvio / Nationalpark Stilfserjoch Stiftung Pro Bartgeier / Fondation Pro Gypaète Supervised by 1 | Page CONTENTS 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 3 Preface .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Observation Protocol and Data Analysis ............................................................................................................................... 3 Weather conditions ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Results .................................................................................................................................... -

Queensborough Community College Fall 2006 Candidates for Graduation Name Maj Maj2 Ahmed Michael La1 Akhta

Academic Senate Agenda – December 12, 2006 – Attachment E QUEENSBOROUGH COMMUNITY COLLEGE FALL 2006 CANDIDATES FOR GRADUATION NAME MAJ MAJ2 AHMED MICHAEL LA1 AKHTAR UZMA DA2 ALAM MOHAMMED BA2 ALBERTI VICTOR DD2 ALI ALAIKA NS2 ALI SARA BT1 ALLEN CHEVELLE NS2 ALVAREZ JEANNE NS2 AMBAT RACHEL NS2 ANCHUNDIA MARGIE LA1 ANDERSON MICHELE LA1 ANDREADIS HELEN LA1 ANDREW AQUILA LA1 ANTONACCI SETH NS2 ARRIGO NATASHA NS2 ARVANITIS DIMITRIOS BT1 AUDI THOMAS LA1 BABAYEVA MAYYA NS2 BACK TONY BT1 BADILLO SARAH LA1 BAEZ SUE ELLEN LA1 BAGLEY NEELY NS2 BALATONI GABOR BT1 BANERJEE SAMIR ME2 BARKER ORIN BM2 BARRICELLA ANTONIETTA BT1 BAZINROUSSEAU VARVARA NS2 BEAUBRUN LANZA LA1 BECKER STEVEN LA1 BEGUM RAHAT LS1 BERTI TATIANA DP2 BIEBER AMY FA1 BIMKA KOOMLEE NS2 BOLIVAR BRYAN BT1 BOONCOME JUDY NS2 BORUKHOVA OLGA NS2 BOSE TITHI LA1 BOTERO MAURICE TM2 BOUGATSOS CLEOPATRA BS2 BOYLE EMILY NS2 BRATHWAITE GREGORY LA1 BROOKS KIMBERLY BS2 BH3 BRYSON JENNAFER LA1 BUDHRAM DIANA LA1 BUJNO RENATA NS2 BUNYI NILDA NS2 BURGOS JESSENIA LS1 BURGOS KEVIN LA1 BUTLER BRENDAN LA1 CAMPANA DINO LA1 CAMPBELL VENECIA LA1 CASALINS ALFREDO ET2 CASILLAS JOSE FA1 CASTILLO ERICA LS1 10 Academic Senate Agenda – December 12, 2006 – Attachment E QUEENSBOROUGH COMMUNITY COLLEGE FALL 2006 CANDIDATES FOR GRADUATION NAME MAJ MAJ2 CASTILLO RANDY LA1 CASTRO JESSICA BS2 CASTRO LINA LA1 CAVIEDES ADRIANA BA2 CERDA VERONICA LA1 CERRATO AMY LA1 CEVALLOS CARLOS BM2 CHADHA PATRICK BM2 CHAN CARL BT1 CHANSKY RACHEL DA2 CHAO JOHN DD2 CHAVEZ CLAUDIA LA1 CHEN HONG BT1 CHEN KO WEI LA1 CHEN WENCHUAN BA2 CHEN -

Last Name First Name City State Province Region Abbate Christine Carol Stream IL Abbate Dawn Silver Lake WI Abbinante Trisha ST

Last name First name City State province region Abbate Christine carol stream IL Abbate Dawn Silver Lake WI Abbinante Trisha ST CHARLES IL Abbott Renee Naperville IL Abcarian Ariane River Forest IL Abe Allison Naperville IL Abens Erin Aurora IL Abraham Sarah FRANKFORT IL AbrahamsonAmanda NAPERVILLE IL Abromitis Barbara GLEN ELLYN IL Abruscato Ashley Oswego IL Accettura Lori MONTGOMERY IL Acker Christine Wheaton IL Acosta Griselda ADDISON IL Acup Fawn Joliet IL Adam Mary Michelle Rockford IL Adams Lin Aurora IL Adams Abigail ELBURN IL Adams Sharyn Indian Head Park IL Adams Jennifer Oswego IL Adams Nian Naperville IL Ader Suzan Morris IL Adolfo Theresa Aurora IL Adorjan Emily Wheaton IL Afryl Carmen Woodridge IL Agarwal Radhika Forest Park IL Agarwal Reema Naperville IL Aggarwal mamta Naperville IL Agpalo Michele Evanston IL Agran Erica Chicago IL Agrawal Ruchi NAPERVILLE IL Aguirre Mary yorville IL Agyepong Tera OAK PARK IL Ahmad Sahar OAK BROOK IL Ahmed Suhayla GLENDALE HTS IL Akhter Sofia Naperville IL Alampi Rochelle Elgin IL Alavi Aimun NILES IL Albert Katie Wheaton IL Albertini Lauryn Naperville IL Albertini Robyn Naperville IL Albrecht Pamela Naperville IL Alcantar Hallie Oswego IL Alcantar Victoria BLUE ISLAND IL Alcantara Lorena Naperville IL Aldrich Dana Naperville IL Ales Cathy Bolingbrook IL Alexa Suzanne Shorewood IL Alexander Jennifer Schaumburg IL Ali Mona Naperville IL Ali Azka Schaumburg IL Allamian Cyndi St. Charles IL Allbright Callie Baton Rouge LA Allen Tarah OSWEGO IL Allen Ava Naperville IL Allen Sunny NAPERVILLE IL -

Graduatoria Finale Di Merito; VISTA La Nota N

MINISTERO DELLA DIFESA DIREZIONE GENERALE PER IL PERSONALE MILITARE IL VICE DIRETTORE GENERALE VISTO il Decreto Legislativo 15 marzo 2010, n. 66, recante “Codice dell’Ordinamento Militare” e successive modifiche e integrazioni; VISTO il Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 15 marzo 2010, n. 90, recante “Testo Unico delle disposizioni regolamentari in materia di Ordinamento Militare” e successive modifiche e integrazioni; VISTO il Decreto Ministeriale 16 gennaio 2013 –registrato alla Corte dei conti il 1° marzo 2013, registro n. 1, foglio 390– concernente tra l’altro struttura ordinativa e competenze della Direzione Generale per il Personale Militare; VISTO l’articolo 66, comma 10 del Decreto Legge 25 giugno 2008 n. 112, convertito con modificazioni dalla Legge 6 agosto 2008, n. 133, il quale richiama, ai soli fini dell’autorizzazione ad assumere, la procedura prevista dall’articolo 35, comma 4 del Decreto Legislativo 30 marzo 2001, n. 165 e successive modificazioni, previa richiesta delle amministrazioni interessate, corredata da analitica dimostrazione delle cessazioni avvenute nell’anno precedente e delle conseguenti economie e dall’individuazione delle unità da assumere e dei correlati oneri, asseverate dai relativi organi di controllo; VISTO il Decreto Dirigenziale n. 635545 emanato dalla Direzione Generale per il Personale Militare il 31 ottobre 2016, pubblicato nella Gazzetta Ufficiale, 4ª Serie Speciale, n. 88 dell’8 novembre 2016, con il quale è stato indetto il concorso pubblico, per titoli ed esami, per l’ammissione al 7° -

Bz Electricians.Pdf

DATE 07/24/2019 TOWN OF HEMPSTEAD TIME 12:02:15 PM BUILDINGS DEPARTMENT BUSINESS ADDRESS REPORTS FOR ELECTRICIANS WHOSE LICENSES WILL EXPIRE FROM 1/1/2016 TO 12/31/2021 LICENSE EXPIRES APPLICANT DOING BUSINESS AS ADDRESS CITY ST ZIP PHONE 12/31/2019 ABAGNALE, PETER J. TRI-CAM ELECTRICAL VENTURES, LLC 339 HICKSVILLE ROAD, UNIT 114 BETHPAGE NY 11714 5169399104 12/31/2017 ABRUZZO, CARL J D ELECTRIC. INC. 14 VALLEY RD BAYVILLE NY 11709 367-9009 12/31/2019 AFFRUNTI, JOSEPH ALBERTSON ELECTRIC INC 901 WILLIS AVE ALBERTSON NY 11507 621-3999 12/31/2019 AFFRUNTI, LAURENCE ALBERTSON ELECTRIC INC 901 WILLIS AVE ALBERTSON NY 11507 621-3999 12/31/2019 AGNELLO, NICHOLAS NELLO ELECTRICAL LLC 449 WELLINGTON ROAD MINEOLA NY 11501 5163612947 12/31/2021 AIELLO, STEVEN STEVEN AIELLO 2077 BEVERLY WAY MERRICK NY 11566 771-7167 12/31/2019 AIMEE, BERNARD ABEX ELECTRIC LLC 3117 ROYAL AVENUE OCEANSIDE NY 11572 536-9133 12/31/2019 ALBERIGO, JOSEPH W. JR. HIGH TECH ELECTRIC 34 TWISTING DRIVE LAKE GROVE NY 11755 6315133513 12/31/2019 ALEXANDER, ENSMAN R. ALKEM ELECTRICAL CORP. 513 ALBANY AVENUE BROOKLYN NY 11203 7189402957 12/31/2019 ALLEN, LARRY S. POSITIVE CONNECTIONS ELECT. INC 88 BROWER AVENUE WOODMERE NY 11598 569-0309 12/31/2020 ALOIA, JOSEPH ALLWAYS ELECTRIC INC. 262 ORINOCO DRIVE BRIGHTWATERS NY 11718 6316660477 12/31/2021 AMABILE, JOSEPH JR. SJ ELECTRIC 228 MERRICK ROAD LYNBROOK NY 11563 596-3600 12/31/2020 AMABILE, ROBERT V AMABILE, ROBERT V 73 DERBY AVENUE GREENLAWN NY 11740 9179391176 12/31/2021 AMMIRATI, JOSEPH ALL COUNTY ELECTRIC 2751 GRAND AVENUE BELLMORE NY 11710 695-6570 12/31/2020 AMORE, DENNIS TRIBOROUGH ELECTRIC, INC. -

Separate and Consolidated Interim Financial Statements As at 30 June 2019

Separate Financial Consolidated Financial Introduction Statements Statements I Separate and Consolidated Interim Financial Statements as at 30 June 2019 Separate and Consolidated Interim Financial Statements as at 30 June 2019 Contents Introduction 5 Interim Separate Financial Statements as at 30 June 2019 13 Interim Consolidated Financial Statements as at 30 June 2019 215 Corporate Directory 288 Introduction Corporate Officers 6 Organisational Structure 7 Introduction from the Chairman of the Board of Directors 8 Financial Highlights 10 Separate Financial Consolidated Financial Introduction 6 Statements Statements Corporate Officers Corporate Officers BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chairman Marcello Foa Chief Executive Fabrizio Salini Officer Directors Rita Borioni Beatrice Coletti Igor De Biasio Riccardo Laganà Giampaolo Rossi Board Secretary Anna Rita Fortuna BOARD OF STATUTORY AUDITORS Chairman until 4 July 2019 as of 5 July 2019 Biagio Mazzotta Carmine di Nuzzo Statutory auditors Roberto De Martino Giovanni Ciuffarella Anna Maria Magro Maria Teresa Mazzitelli Alternative auditors M.M. Assunta Protopapa Pietro Contaldi Pietro Floriddia Antonella Damiotti EXTERNAL AUDITOR PricewaterhouseCoopers Separate Financial Consolidated Financial Introduction Statements Statements 7 Organisational Structure Organisational Structure (short form) Board Chairperson of Directors of the Board Board of Statutory Auditors Internal Supervisory Audit Board Chief Executive Officer(1) General Management Corporate Mastheads TV channels Corporate CFO - Finance and genres and Support and Planning Radio COO - TV production CFO - Technological Property and Infrastructure local sites Rai Cinema Rai Com Rai Pubblicità Rai Way (1) Among others, the Staff Departments of the Chief Executive Officer and Corporate General Manager, International Relations (functionally reporting to the Chairman of the Board), Institutional Relations, Communication, Marketing and Research report to the Chief Executive Officer. -

Lista De Apellidos Italianos A

Lista de apellidos italianos 1 A Abate Accetta Aeiario Agresti Alberico Algieri Abatecola Acciaro Aequaviva Agri Albertanti Alia Abatemarco Accico Affatato Agricola Alberti Aliamian Abateminnici Accieri Affitto Agrig Albertinello Alicante Abatescianni Accomando Affranti Agrignola Alberto Alice Abba Accomano Affronto Agrillo Albertonino Aliceti Abbadessa Acconiando Africano Agro Alberts Alicino Abbado Accoramboni Agabiti Aguglia Albicocchi Alifante Abbali Accorimboni Agamenone Agugliaro Albizi Alini Abbamonti Accorinti Agata Aguibsue Alceini Alio Abbate Accoroni Agatone Agurbeue Alcide Alioto Abbati Accursio Agelli Ahianm Alcionis Aliperti Abbia Acerbi Aggardati Aidone Aldana Aliso Abbinante Aceto Agilufo Aiello Aldi Alista Abbinanti Achillini Agli Aimone Aldobrandini Alla Abbinzo Acicaferro Aglialoro Aina Aldorisi Allabastro Abbomonte Acinello Aglie Airllo Alduino Allegra Abbruscato Acione Aglietta Airola Alednl Allegranti Abele Acocella Aglietti Aiutamicristo Alegrette Allegranza Abello Acqua Agliettie Ajala Aleo Allegri Aberta Acquafredda Aglione Ajolo Ales Allevi Abetti Acquaro Agnelli Ajuto Alesci Allgero Abisso Acquaruolo Agnello Alagna Alesi Alliegro Ablmane Acquistapace Agnese Alaimo Alessandra Allo Abrami Acuto Agnisio Alairo Alessandri Allocchi Abruzzese Adami Agno Alamanno Alessandro Allodi Abruzzi Adamo Agnolillo Alammi Alessi Alloggio Abruzzini Adamol Agnusdei Alampi Alessia Allori Abruzzo Adamollo Ago Alano Alessich Allotta Abtato Adamolo Agolante Alaro Alessie Almagro Abuiso Addario Agoli Alba Alessio Almelo Acardi Addiego -

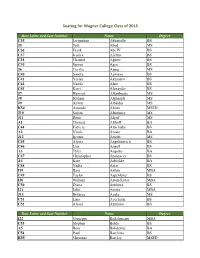

Seating for Wagner College Class of 2015

Seating for Wagner College Class of 2015 Row Letter and Seat Number Name Degree C35 Jacqueline Abbatiello BS J5 Faiz Abed MS C36 Frank Abt IV BS C37 Jessica Afeltra BS C38 Chantal Agnew BS C39 Steven Agro BS J6 Cecilia Ajang MS C40 Sandra Ajimavo BS C41 Yuliya Akhsanov BS C42 Nazifa Alam BS C43 Kerri Alexander BS J7 Hamzah Alfarshooty MS J8 Hitham Alghamdi MS J9 Anwar Alhaider MS K54 Amanda Alioto MSED J10 Sultan Alnomasy MS J11 Rana Alsaif MS A1 Thomas Althoff BA C44 Patricia Altschuler BS A2 Nicole Amato BA J12 Ijeoma Amobi MS C45 Alyssa Angelinovich BS C46 Lisa Angell BS A3 Tyler Angotto BA C47 Christopher Antonacci BS A4 Kate Arbuckle BA C48 Nadia Asfar BS I19 Bara Asfour MBA C49 Taylor Aspenleiter BS I20 William Aston-Reese MBA C50 Diana Attakora BS I21 John Avona MBA J13 Brittney Ayala MS C51 Lina Ayechemi BS C52 Alyssa Azzinaro BS Row Letter and Seat Number Name Degree I22 Giuseppe Badalamenti MBA C53 Stephen Baldo BS A5 Besa Balidemaj BA C54 Paul Barchitta BS K55 Christina Barclay MSED A6 DaeVonte Barnett BA C55 Patrick Barrieu BS J14 Blake Bascom MS C56 Anthony Battaglia BS J15 Michael Beck Jr. MS A7 Samantha Bedker BA C57 Shanaaz Begum BS C58 Jennifer Beliard BS D1 Candice Bellocchio BS D2 Katherine Bender BS D3 Alexandria Berardi BS A8 Ian Bertschausen BA J16 Judith Betz MS D4 Mark Beyer BS A9 Alissa Bianculli BA D5 Marcella Biordi BS D6 Steven Bloodworth BS D7 Courtney Boardman BS A10 Kaycee Bock BA I23 Eric Boskey MBA I24 William Bradley MBA D8 Geoffrey Bradley BS A11 Katharine Bragg BA A12 Desiree Braithwaite BA D9 Danielle -

Iacp New Members

44 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 200 | Alexandria, VA 22314, USA | 703.836.6767 or 1.800.THEIACP | www.theIACP.org IACP NEW MEMBERS New member applications are published pursuant to the provisions of the IACP Constitution. If any active member in good standing objects to an applicant, written notice of the objection must be submitted to the Executive Director within 60 days of publication. The full membership listing can be found in the online member directory under the Participate tab of the IACP website. Associate members are indicated with an asterisk (*). All other listings are active members. Published January 1, 2020. Australia New South Wales Prairiewood Koutsoufis, Andrew, Detective Superintendent, New South Wales Police Force Queensland Brisbane Pilotto, Andrew, Commander, Queensland Police Service Victoria Docklands Guenther, Ross, Assistant Commissioner, Victoria Police Service Brazil Rio de Janeiro Rio de Janeiro Fernandes da Silva Moca, Fabricio, Lieutenant Colonel, Rio de Janeiro State Military Police São Paulo Marilia Tonini, Mirio Celso, Captain, Policia Militar do Estado de Sao Paulo Piracicaba Gonzales, Pablo, Captain, Policia Militar do Estado de Sao Paulo Sao Paulo de Godoy, Flavia Feliciano, CB PM, Policia Militar do Estado de Sao Paulo de Mendonca, Fabiano Soares, Captain, Policia Militar do Estado de Sao Paulo Kitsuwa, Mario, Major, Policia Militar do Estado de Sao Paulo Rodrigues Rosa, Hudson Arthur, Captain, Policia Militar do Estado de Sao Paulo Canada Alberta Calgary *Barrett, Nicole, Sergeant, Calgary Police Service