X a Place in the Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smashing Pumpkins Gish Mp3, Flac, Wma

Smashing Pumpkins Gish mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Gish Country: Mexico Released: 2011 Style: Alternative Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1418 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1777 mb WMA version RAR size: 1689 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 399 Other Formats: ASF TTA AAC MP4 AU AC3 RA Tracklist 1 I Am One 4:07 2 Siva 4:20 3 Rhinoceros 6:30 4 Bury Me 4:46 5 Crush 3:34 6 Suffer 5:08 7 Snail 5:09 8 Tristessa 3:32 9 Window Paine 5:49 10 Daydream 3:08 Credits Bass – D'arcy Co-producer [Reissue] – Dennis Wolfe Design [Reissue], Layout [Reissue] – Noel Waggener Drums – Jimmy Chamberlin Guitar – James Iha Guitar, Photography By [Postcard Photos ©] – Billy Corgan Management [Legal Saviour] – Jill Berliner Mastered By – Evren Goknar* Photography By [Cover Photos] – Robert Knapp Photography By [Inner Photos Courtesy Of] – Billy Corgan, Jimmy Chamberlin, Robert Knapp Producer [Original Album] – Billy Corgan, Butch Vig Producer [Reissue] – Billy Corgan, David K. Tedds, Kerry Brown, Michael Murphy Remastered By – Bob Ludwig Vocals – Billy Corgan Written-By – Billy Corgan Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5 099967 928828 Other versions Title Category Artist Label Category Country Year (Format) Smashing Gish (CD, Caroline CAROL 1705-2 CAROL 1705-2 US 1991 Pumpkins* Album) Records Gish (LP, Hut HUTLPX 2, 7243 Smashing HUTLPX 2, 7243 Album, RE, Recordings, UK 1994 8 39663 1 8 Pumpkins* 8 39663 1 8 RM) Virgin Caroline Gish (LP, CARLP 16, 211 Smashing Records, CARLP 16, 211 Album, RP, Europe Unknown 651 Pumpkins* Caroline 651 whi) Records -

“When I Listen to Gish,” Billy Corgan Says Today

“When I listen to Gish,” Billy Corgan says today, “what I hear is a beautiful naïveté.” They say you never forget the first time, and even twenty years later, the 1991 debut album by Smashing Pumpkins –– guitarist and vocalist Corgan, drummer Jimmy Chamberlin, bassist D’arcy Wretzky and guitarist James Iha –– remains the unforgettable start of a musical conversation that continues to resonate with millions of fans all around the world. In retrospect, Gish can clearly be heard as a groundbreaking album in the history of what would soon become more much widely known as alternative rock. Gish was, after all, the promising debut of a band that would help alternative rock quickly become part of a new, grungier mainstream. But back in the beginning, Gish was simply the memorable opening salvo by a band from Chicago that really didn’t fit in anywhere in the rock world –– that is, until bands like Smashing Pumpkins helped change the rock world once and for all. To hear Corgan tell it now, Smashing Pumpkins came by their beautiful naïveté naturally. “We’d had very little exposure to the national stage,” he explains. “There’s no way that if we had been exposed to all of what was going on in New York and L.A. earlier, we would have made Gish. This is one of those weird albums that sounds like it came from some guy who crawls up out of the basement holding a record in his hands proudly –– a little like the first time we heard Dinosaur Jr. You think, ‘who the hell is this? And where did that come from?’ ” According to Corgan, the album originally came from Smashing Pumpkins’ early vow of poverty. -

Powers of Horror; an Essay on Abjection

POWERS OF HORROR An Essay on Abjection EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES: A Series of the Columbia University Press POWERS OF HORROR An Essay on Abjection JULIA KRISTEVA Translated by LEON S. ROUDIEZ COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS New York 1982 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Kristeva, Julia, 1941- Powers of horror. (European perspectives) Translation of: Pouvoirs de l'horreur. 1. Celine, Louis-Ferdinand, 1894-1961 — Criticism and interpretation. 2. Horror in literature. 3. Abjection in literature. I. Title. II. Series. PQ2607.E834Z73413 843'.912 82-4481 ISBN 0-231-05346-0 AACR2 Columbia University Press New York Guildford, Surrey Copyright © 1982 Columbia University Press Pouvoirs de l'horreur © 1980 Editions du Seuil AD rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Clothbound editions of Columbia University Press books are Smyth- sewn and printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Contents Translator's Note vii I. Approaching Abjection i 2. Something To Be Scared Of 32 3- From Filth to Defilement 56 4- Semiotics of Biblical Abomination 90 5- . Qui Tollis Peccata Mundi 113 6. Celine: Neither Actor nor Martyr • 133 7- Suffering and Horror 140 8. Those Females Who Can Wreck the Infinite 157 9- "Ours To Jew or Die" 174 12 In the Beginning and Without End . 188 11 Powers of Horror 207 Notes 211 Translator's Note When the original version of this book was published in France in 1980, critics sensed that it marked a turning point in Julia Kristeva's writing. Her concerns seemed less arcane, her presentation more appealingly worked out; as Guy Scarpetta put it in he Nouvel Observateur (May 19, 1980), she now intro- duced into "theoretical rigor an effective measure of seduction." Actually, no sudden change has taken place: the features that are noticeable in Powers of Horror were already in evidence in several earlier essays, some of which have been translated in Desire in Language (Columbia University Press, 1980). -

Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy – Inferno

DIVINE COMEDY -INFERNO DANTE ALIGHIERI HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND NOTES PAUL GUSTAVE DORE´ ILLUSTRATIONS JOSEF NYGRIN PDF PREPARATION AND TYPESETTING ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND NOTES Henry Wadsworth Longfellow ILLUSTRATIONS Paul Gustave Dor´e Released under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial Licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ You are free: to share – to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work; to remix – to make derivative works. Under the following conditions: attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work); noncommercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes. Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. English translation and notes by H. W. Longfellow obtained from http://dante.ilt.columbia.edu/new/comedy/. Scans of illustrations by P. G. Dor´e obtained from http://www.danshort.com/dc/, scanned by Dan Short, used with permission. MIKTEXLATEX typesetting by Josef Nygrin, in Jan & Feb 2008. http://www.paskvil.com/ Some rights reserved c 2008 Josef Nygrin Contents Canto 1 1 Canto 2 9 Canto 3 16 Canto 4 23 Canto 5 30 Canto 6 38 Canto 7 44 Canto 8 51 Canto 9 58 Canto 10 65 Canto 11 71 Canto 12 77 Canto 13 85 Canto 14 93 Canto 15 99 Canto 16 104 Canto 17 110 Canto 18 116 Canto 19 124 Canto 20 131 Canto 21 136 Canto 22 143 Canto 23 150 Canto 24 158 Canto 25 164 Canto 26 171 Canto 27 177 Canto 28 183 Canto 29 192 Canto 30 200 Canto 31 207 Canto 32 215 Canto 33 222 Canto 34 231 Dante Alighieri 239 Henry Wadsworth Longfellow 245 Paul Gustave Dor´e 251 Some rights reserved c 2008 Josef Nygrin http://www.paskvil.com/ Inferno Figure 1: Midway upon the journey of our life I found myself within a forest dark.. -

Teacher's Guide

Teacher’s Guide Dear Educator, Welcome to Backyard Monsters! The enclosed materials have been designed to provide an educational and enjoyable experience for you and your students. This guide includes background information; vocabulary; student pre-/post-visit materials; a Museum visit worksheet; and references. These materials are most appropriate for grades 2–6 and may be adjusted for other grade levels. References to California Content Standards are included where appropriate. Bold lettering indicates glossary words. If you have questions related to this guide, please call the Museum Education Department at 619.255.0202 or email [email protected]. Contents Exhibit Overview 2 Crash Course in Entomology 2 Glossary 8 Classroom Activities 10 Live Insect Study all grades 10 Scent Messages grades K–2 12 Blending In and Standing Out grades 2–3 13 Reading and Writing grades 4–5 15 Arthropod Classifi cation grades 6–8 16 Newsworthy Arthropods grades 6–8 18 Museum Visit Worksheet 20 Answers 21 Resources 21 Credits 22 Addendum 23 Bonus Activity www.sdnhm.org/exhibits/bym/bym_drawbug.pdf © San Diego Natural History Museum 1 Teacher’s Guide Classroom Activities Live Insect Study Suggested Grade Level: all grades Objectives: to observe and record insect behavior; to chart and analyze daily rhythms of patterns in behavior. California Science Content Standards: Life Science K—2a, c observing, identifying major structures 1—2a, b, c needs of plants and animals 2—2b, d life cycles, individual variations; adaptation 3—3a adaptation 4—2a energy and food chains 5—2a animals have special structures 6—5a energy and food chains 7—5a organisms have levels of organization Investigation and Experimentation K—4a observation and interpretation 4—4a differentiate observation from inference Materials: live crickets, aquarium with lid, food and water, shelter, heat and light source Introduction Live insects are wonderful, low-maintenance classroom pets. -

Smashing Pumpkins Unplugged Rar

Smashing Pumpkins Unplugged Rar 1 / 6 Smashing Pumpkins Unplugged Rar 2 / 6 3 / 6 Bugg Superstar 07 I Am One (Live in Barcelona, 1993) 08 Smashing Pumpkins Unplugged Rarities And B-sides WikiPulseczar 09. 1. smashing pumpkins unplugged 2. smashing pumpkins unplugged mtv 3. smashing pumpkins unplugged mtv full Soma (Live in London, 1994) 10 Slunk (Live on Japanese TV, 1992) 11 French Movie Theme 12. smashing pumpkins unplugged smashing pumpkins unplugged, smashing pumpkins unplugged mtv, smashing pumpkins unplugged vinyl, smashing pumpkins unplugged album, smashing pumpkins unplugged mtv full, smashing pumpkins unplugged cd, smashing pumpkins unplugged 1993, smashing pumpkins cherub rock unplugged, smashing pumpkins mayonaise unplugged, smashing pumpkins disarm unplugged, smashing pumpkins acoustic, smashing pumpkins acoustic songs, smashing pumpkins acoustic chords, smashing pumpkins acoustic tab, smashing pumpkins acoustic vinyl Ntfs For Mac Os Mojave Jun 3, 2012 - Of rar Fuck You (An Ode To No One) 09 Cupid De Locke 11 Galapogos 12.. Slow Dawn 02 Saturnine 04 Glass Theme (Spacey) EP2 01 Soul Power (James Brown cover) 02. Vmware Ethernet Controller Driver Windows 2008 R2 E1000 4 / 6 download microsoft office for mac free torrent smashing pumpkins unplugged mtv Inno Setup Script Silent Install Script Silverfuck / Over The Rainbow (Live in London 1994) 15 Why Am I So Tired? Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness () Official Album 1995 Disc 1: Dawn To Dusk 01.. Encyclopedia britannica full version software Stumbleine 09 We Only Come Out At Night 11.. Thirty-Three 04 In The Arms Of Sleep 05 Tales Of Scorched Earth 07 Thru The Eyes Of Ruby 08.. Try, Try, Try (Version 1 Alternate Text) 03 Heavy Metal Machine (Version 1 Alternate Mix) LP 01. -

(703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190

1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION THE GAZA/LEBANON CRISIS Washington, D.C. Monday, July 17, 2006 MODERATOR: KENNETH POLLACK Senior Fellow and Director of Research Saban Center for Middle East Policy, The Brookings Institution PANELISTS: MARTIN INDYK Senior Fellow and Director Saban Center for Middle East Policy, The Brookings Institution NAHUM BARNEA Kreiz Visiting Fellow, Saban Center Senior Political Analyst, Yediot Aharanot HISHAM MILHEM Washington Correspondent, Al-Nahar SHIBLEY TELHAMI Nonresident Senior Fellow, Saban Center Anwar Sadat Professor, University of Maryland Anderson Court Reporting 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. POLLACK: Good morning, welcome to the Saban Center at the Brookings Institution. We are delighted that you could all join us here so early on a blazingly hot Monday morning. First, there are a number of seats up front. So those of you who are standing in the back, if you would like to take a load off and come sit, there are plenty of seats up in and around here hidden amongst various other people. We are very pleased to have this gathering with us. Obviously, the developments in Israel, the Palestinian Territories, and Lebanon over the previous five days have captured the headlines across the globe, and I think that there are questions in everyone’s mind as to where this is going to go and where it is going to end. For the first time in a long time, there are people talking about a much wider war in the Middle East. -

The Canterbury Tales

The Canterbury Tales Geoffrey Chaucer The Canterbury Tales Table of Contents The Canterbury Tales.........................................................................................................................................1 Geoffrey Chaucer.....................................................................................................................................1 i The Canterbury Tales Geoffrey Chaucer • Prologue • The Knight's Tale • The Miller's Prologue • The Miller's Tale • The Reeve's Prologue • The Reeve's Tale • The Cook's Prologue • The Cook's Tale • Introduction To The Lawyer's Prologue • The Lawyer's Prologue • The Lawyer's Tale • The Sailor's Prologue • The Sailor's Tale • The Prioress's Prologue • The Prioress's Tale • Prologue To Sir Thopas • Sir Thopas • Prologue To Melibeus • The Tale Of Melibeus • The Monk's Prologue • The Monk's Tale • The Prologue To The Nun's Priest's Tale • The Nun's Priest's Tale • Epilogue To The Nun's Priest's Tale • The Physician's Tale • The Words Of The Host • The Prologue To The Pardoner's Tale • The Pardoner's Tale • The Wife Of Bath's Prologue • The Tale Of The Wife Of Bath • The Friar's Prologue • The Friar's Tale • The Summoner's Prologue • The Summoner's Tale • The Clerk's Prologue • The Clerk's Tale • The Merchant's Prologue • The Merchant's Tale • Epilogue To The Merchant's Tale • The Squire's Prologue • The Squire's Tale • The Words Of The Franklin And The Host • The Franklin's Prologue • The Franklin's Tale • The Second Nun's Prologue • The Second Nun's Tale The Canterbury Tales 1 The Canterbury Tales • The Canon's Yeoman's Prologue • The Canon's Yeoman's Tale • The Manciple's Prologue • The Manciple's Tale Of The Crow • The Parson's Prologue • The Parson's Tale • The Maker Of This Book Takes His Leave This page copyright © 1999 Blackmask Online. -

Table of Contents Pagan Songs and Chants Listed Alphabetically By

Vella Rose’s Pagan Song Book August 2014 Edition This is collection of songs and chants has been created for educational purposes for pagan communities. I did my best to include the name of the artists who created the music and where the songs have been recorded (please forgive me for any errors). This is a work in progress, started over 12 years ago, a labor of love, that has no end. There are and have been many wonderful artists who have created music for our community. Please honor them by acknowledging them if you include their songs in your rituals or song circles. Many of the songs are available on the web, some additional resources are included in Appendix A to help you find them. Blessings and thanks to all. NOTE: Page numbers only works to 170 – then something went wrong and I can’t figure it out, sorry. Table of Contents Pagan Songs and Chants Listed Alphabetically By Title p. 2 - 160 Appendix A – Additional Resources p. 161 Appendix B – Song lists from select albums p. 163 Appendix C – Songs and Chants for Moons and Sabbats Appendix D – Songs and Chants for Winter and Yule Appendix E – Songs for Goddesses Index – Alphabetical listings by First Lines (verses and chorus) 1 Vella Rose’s Pagan Song Book August 2014 Alphabetical Listing of Songs by Title A Circle is Cast By Anna Dempska, Recorded on “A Circle is Cast” by Libana (1988). A circle is cast, again, and again, and again, and again. (repeats) ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** Air Flies to the Fire Recorded on “Good Where We Been” by Shemmaho. -

Congressional Record—House H2392

H2392 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE March 26, 2003 I have one example, though, of a world knew that. But, in France, it If the gentleman would like to make company. USAID, which is a foreign seems like they were all united against any closing comments, I need to actu- aid branch, it does a lot of good things, the United States and against this war. ally make an engagement. but it is going to let some humani- Apparently, that is not a problem to Mr. MARIO DIAZ-BALART of Flor- tarian contracts go, and French and Sedxho, because they are a French ida. Mr. Speaker, I just want to thank German companies will be eligible to company. And yet here are the Ma- the gentleman from Georgia. Again, I compete for it. That bothers me a lot, rines, the brave and the honorable Ma- had to come to the floor today once I that they will be able to profit from rines who are the ones who discovered was hearing what he was talking this war. this hospital today, allegedly a hos- about. I had to come here and thank Mr. MARIO DIAZ-BALART. I could pital, and yet 55 different garrisons in the gentleman, thank him for standing not agree with the gentleman more, if the United States of America, when an up for our troops, thank him for sup- the gentleman will yield, Mr. Speaker. 18-year-old Marine sits down for lunch, porting our troops, thank him for sup- This is a two-fold problem. There is, a French company is making a profit porting the President of the United first, the opposition to this effort to from that. -

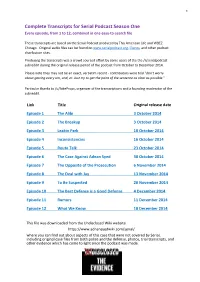

Serial Podcast Season One Every Episode, from 1 to 12, Combined in One Easy-To-Search File

1 Complete Transcripts for Serial Podcast Season One Every episode, from 1 to 12, combined in one easy-to-search file These transcripts are based on the Serial Podcast produced by This American Life and WBEZ Chicago. Original audio files can be found on www.serialpodcast.org, iTunes, and other podcast distribution sites. Producing the transcripts was a crowd sourced effort by some users of the the /r/serialpodcast subreddit during the original release period of the podcast from October to December 2014. Please note they may not be an exact, verbatim record - contributors were told "don't worry about getting every um, and, er. Just try to get the point of the sentence as clear as possible." Particular thanks to /u/JakeProps, organizer of the transcriptions and a founding moderator of the subreddit. Link Title Original release date Episode 1 The Alibi 3 October 2014 Episode 2 The Breakup 3 October 2014 Episode 3 Leakin Park 10 October 2014 Episode 4 Inconsistencies 16 October 2014 Episode 5 Route Talk 23 October 2014 Episode 6 The Case Against Adnan Syed 30 October 2014 Episode 7 The Opposite of the Prosecution 6 November 2014 Episode 8 The Deal with Jay 13 November 2014 Episode 9 To Be Suspected 20 November 2014 Episode 10 The Best Defense is a Good Defense 4 December 2014 Episode 11 Rumors 11 December 2014 Episode 12 What We Know 18 December 2014 This file was downloaded from the Undisclosed Wiki website https://www.adnansyedwiki.com/serial/ where you can find out about aspects of this case that were not covered by Serial, including original case files from both police and the defense, photos, trial transcripts, and other evidence which has come to light since the podcast was made. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Title Page

Celtic Groves Lyric Book TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page THE DIVINE .................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Ancient Mother .................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Aphrodite, Dionysus .......................................................................................................................................... 2 3. As You Go ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 4. Cerridwyn's Cauldron ........................................................................................................................................ 3 5. Ecco, Ecco ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 6. Every Woman Born ........................................................................................................................................... 3 7. Freya, Shakti ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 8. Give Thanks ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 9. God Chant (Pan, Poseidon, Dionysus…)