A Study on Immigrant Women in the Flemingdon Park Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

Food Banks & Food Resources Near Thorncliffe Park & Flemingdon Park

Updated April 8th, 2020 Food Banks & Food Resources Near Thorncliffe Park & Flemingdon Park Food Access / Name / Address Contact Info Note(s) Office Hours - Must call ahead Thorncliffe Park Food Bank Food Access: Tel: 647-428-9755 - Register online using this link for food 1 Leaside Park Drive, Unit 5B *Delivery Only* Website: https://icnareliefcanada.ca/covid19 baskets that are delivered. Click “Need Toronto, ON M4H 1R1 Food?” to register. Food Access: Tel: 416-422-4322 Flemingdon Park Food Bank Mon & Wed 10 Gateway Blvd (Basement) Email: [email protected] - Must call ahead (12:00 – 3:30pm) Toronto, ON M3C 3A1 *Must Call Agead* Website: https://www.fcfoodbank.com/ Maryam Ali Latif: Afghan Women’s [email protected] / 416-422-2225 - Must call and leave message for call-back Food Access: Organization Food Bank - Priority for seniors / single parent families Monday Mornings Ext 227 747 Don Mills Road, Unit 200 - Delivery may be possible for clients with *By Appointment Only* Toronto, ON, M3C 1T2 Nooria Amiri: [email protected] / mobility challenges 416-388-8323 Community Share Food Bank Tel: 416-441-3209 - Need proof of residence in catchment area 33 Overland Drive - Catchment: Highway 401 to Eglinton Ave Food Access: Email: [email protected] Toronto, M3C 2C3 (north side of street) and Bayview Ave (east *By Appointment Only* Website: (Church of the Ascension, rear side of street) to Victoria Park Ave (west side entrance) https://www.communitysharefoodbank.ca/ of street) Meal / Grocery Delivery in East York/North -

The Hidden Epidemic a Report on Child and Family Poverty in Toronto

THE HIDDEN EPIDEMIC A Report on Child and Family Poverty in Toronto The hidden epidemic A Report on Child and Family Poverty in Toronto November 2014 1 Acknowledgements This report was researched and written by a working group consisting of: Michael Polanyi Children’s Aid Society of Toronto and Alliance for a Poverty-Free Toronto Lesley Johnston Social Planning Toronto Anita Khanna Family Service Toronto/Ontario Campaign 2000 Said Dirie Children’s Aid Society of Toronto and Alliance for a Poverty-Free Toronto michael kerr Colour of Poverty – Colour of Change and Alliance for a Poverty-Free Toronto Research and data analysis support provided by the City of Toronto is gratefully acknowledged. Financial support was provided by the Children’s Aid Society of Toronto and the Children’s Aid Foundation’s Community Initiatives Program. Editing and design support was provided by Tilman Lewis and Peter Grecco. We thank Ann Fitzpatrick, Christa Freiler, Skylar Maharaj, Laurel Rothman and Alex Tranmer for their review of and assistance with the paper. THE HIDDEN EPIDEMIC A Report on Child and Family Poverty in Toronto Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 3 2. Current Levels of Child and Family Poverty in Toronto and Beyond 6 3. Which Toronto Children Are Affected by Poverty? 9 Geography 9 Ethno-racial Background 12 Indigenous Communities 13 Immigration or Citizenship Status 13 Disability 13 Family Structure 13 4. Growing Up in poverty – Reality and impacts on children in Toronto 14 Access to Nutrition 14 Access to Housing 16 Access to Education 17 Access to Recreation 19 5. Underlying Causes of Family Poverty 20 Inadequate Employment Income 20 Inadequate Income Supports and Community Services 22 Lack of Access to Affordable Public Services 24 6. -

Community Benefits Quarterly

EGLINTON CROSSTOWN Community Benefits and Liaison Plan Summary & Progress To-Date 6 201 DECEMBER Photo: Crosslinx Transit Solutions, 2016. Transit Crosslinx Photo: Photo: Crosslinx Transit Solutions, 2016. I. INTRODUCTION Metrolinx and Infrastructure Ontario selected Crosslinx Transit Solutions to design, build, finance and maintain the Eglinton Crosstown Light Rail Transit (ECLRT) project, the first major transit expansion in 50 years. The provincial government’s $5.3 billion Crosstown investment is the single largest GTA transit investment ever. When it’s up and running, the Crosstown will deliver service that is reliable, comfortable and 60 percent faster than what is now available. What’s more, building the line is creating thousands of jobs, 2,500 at peak construction, and other significant economic benefits. The Crosstown is also unique because it is Ontario’s first large- scale public infrastructure project to contractually require the developer, CTS, to ensure that local communities and historically disadvantaged and equity seeking groups directly benefit from the province’s investment. Historically disadvantaged and equity seeking groups (H&E) refer to groups that have been historically excluded or marginalized from the processes and decisions that affect them. To meet this requirement, CTS is providing a range of employment, training and apprenticeship opportunities to these groups, as well as purchasing goods and services from local suppliers and social enterprises, whenever possible. 1 Photo: Crosslinx Transit Solutions, 2016. II. PROJECT AGREEMENT REQUIREMENTS Eglinton Crosstown Project Agreement Requirements The objective of the Community Benefits and Liaison Plan Community Benefits is to maximize training, employment and procurement The Project Agreement mandates a plan that includes: opportunities for Eglinton-area residents and businesses. -

Rockcliffe-Smythe Residents

West Toronto Local Collaborative Priority Area: Rockcliffe Smythe – Focus on Chronic Diseases and Access to Primary Care May 26, 2017 Contents 1. Rockcliffe Smythe background and methodology/considerations/limitations of this deep dive analysis 2. Overall Emergency Department and Acute Inpatient Utilization for Selected Chronic Conditions for Rockcliffe-Smythe residents 3. ED and Acute Inpatient Utilization for Individual Selected Chronic Conditions for Rockcliffe-Smythe residents 4. Patient Journey for Residents with ED Visits, Health Links and Home Care Referrals and Use 5. Primary Care Attachment, Access and Continuity for Rockcliffe-Smythe Residents 6. Community providers serving Rockcliffe-Smythe residents (CBI) 7. Appendix a) Diagnostic codes for the selected chronic conditions 2 West Toronto Sub-Region – Rockcliffe-Smythe Neighbourhood 3 Rockcliffe-Smythe – Background information on chronic conditions identified through previous data review and consultations Previous analyses showed that Rockcliffe-Smythe: Was one of the 4 neighborhoods in the northwest corner with a high prevalence of chronic diseases (Diabetes, Asthma, high blood pressure and COPD) Had high rate of seniors (ages 65+) living alone (36.8%), High Proportion of immigrants (51.0%) High rate of individuals with no knowledge of English or French (6.3%), Second highest marginalization rate in the West sub-regions and a high rate of persons living below low income measure (after-tax) (23.1%), It is a City of Toronto designated Neighborhood Improvement Areas (NIA) -

Community Needs Assessment Survey Report

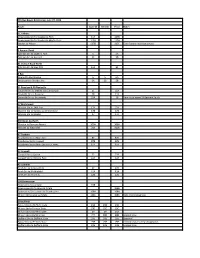

Community Needs Assessment Survey Report April 2017 Urooj Fatima Iftikhar Placement Student, MPH Programme University of Waterloo Community Need Assessment Survey 2 Table of Contents Background: .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Demographic information:........................................................................................................................... 3 Preferences to access the services: ............................................................................................................. 3 Need of the services: .................................................................................................................................... 3 Strengths:...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Limitations: ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Conclusion: ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Annexes: ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 Table 1: Demographic of the survey Participants .................................................................................. -

TTC Bus Route Relettering June 22, 2014 Route Current Interim Final

TTC Bus Route Relettering June 22, 2014 Route Current Interim Final Notes 117 Alness Downsview Stn To Steeles via Flint 117 117B Downsview Stn To Steeles via Martin Ross 117A 117A Steeles to Wilson 117B 117C Early Sunday morning service 5 Avenue Road Eglinton Stn to Queen's Park 5 5A Eglinton Stn to Gerrard 5C 5B 61 Avenue Road North Eglinton Stn to Hwy 401 61A 61 6 Bay Dupont to Sherbourne 6 6 6A Davenport to Sherbourne 6A 6B 6B 11 Bayview & 28 Davisville Davisville Stn to Steeles via Sunnybrook 11 11A Davisville Stn to Bayview 28 11B Davisville Stn to Brickworks 28A 28 New route name 28 Bayview South 17 Birchmount Warden Stn to 14th Ave 17A 17A Warden Stn to Steeles via Wintermute 17B 17B Warden Stn to Steeles 17 17C 300 Bloor-Danforth Warden to Pearson Airport 300A 300A Warden to West Mall 300 300B 87 Cosburn Broadview Stn to Main Stn 87 87C Broadview Stn to Coxwell 87B 87B Broadview Stn to Main Stn via EY Acres 87A 87A 22 Coxwell Coxwell Stn to Queen 22 22B Coxwell Stn to Victoria Park 22A 22A 42 Cummer Finch Stn to Victoria Park 42 42C Finch Stn to Middlefield 42A 42A Finch Stn to Kennedy 42B 42B 108 Downsview Downsview Stn to Jane 108 Downsview Stn to Jane via Arleta 108B Downsview Stn to Jane via Grandravine 108A 108A Wilson Stn to Jane via Arleta 108C 108C Early morning service 29 Dufferin Tycos Drive to Dufferin Gate 29A 29B 29B Wilson Stn to Princes' Gate 29D 29C 29C Wilson Stn to Dufferin Gate 29 29 29A Wilson Stn to Dufferin Stn ??? 29D 29D Limited trips Dufferin Stn to Dufferin Gate 29E 29E 29E Seasonal Tycos Drive to Princes' -

Low Other* Dwelling Density Availability of Destinations

21 24 116 130 2 35 36 50 49 48 27 131 22 34 37 117 129 3 25 51 52 47 46 4 132 26 38 53 118 1 5 33 40 128 135 134 23 39 45 6 29 113 28 32 105 133 31 41 42 119 126 137 7 8 30 103 127 136 115 112 108 102 43 125 100 138 140 11 10 110 109 101 99 44 9 111 107 104 56 55 139 106 124 Dwelling Availability of 91 92 97 54 120 density destinations 13 90 94 96 58 123 15 89 98 57 High - High 12 114 93 59 60 14 88 95 67 61 121 83 74 66 High - Low 87 80 79 71 68 69 62 16 75 64 122 86 84 81 78 76 65 Low - High 7372 63 85 70 Low - Low 20 17 82 77 Other* 18 19 0 2.5 5 km * Indicates DB belonged to the middle quintile of Neighbourhoods dwelling density and/or availability of destinations 1 West Humber-Clairville 25 Glenfield-Jane Heights 49 Bayview Woods-Steeles 73 Moss Park 96 Casa Loma 121 Oakridge 2 Mount Olive-Silverstone- 26 Downsview-Roding-CFB 50 Newtonbrook East 74 North St. James Town 97 Yonge-St.Clair 122 Birchcliffe-Cliffside Jamestown 27 York University Heights 51 Willowdale East 75 Church-Yonge Corridor 98 Rosedale-Moore Park 123 Cliffcrest 3 Thistletown-Beaumond Heights 28 Rustic 52 Bayview Village 76 Bay Street Corridor 99 Mount Pleasant East 124 Kennedy Park 4 Rexdale-Kipling 29 Maple Leaf 53 Henry Farm 77 Waterfront Communities- 100 Yonge-Eglinton 125 Ionview 5 Elms-Old Rexdale 30 Brookhaven-Amesbury 54 O'Connor-Parkview The Island 101 Forest Hill South 126 Dorset Park 6 Kingsview Village-The Westway 31 Yorkdale-Glen Park 55 Thorncliffe Park 78 Kensington-Chinatown 102 Forest Hill North 127 Bendale 7 Willowridge-Martingrove-Richview 32 Englemount-Lawrence -

Toronto North Local Immigration Partnership

Toronto North Settlement and Employment Strategy October 2012 F I N A L Submitted to Citizenship and Immigration Canada October 31, 2012 Table of Contents Welcoming Toronto’s Future ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 The Role of Local Immigration Partnerships ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Overview ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Toronto North LIP – History and Catchment ................................................................................................................................ 3 Toronto North Newcomer Demographic and Needs Profile ............................................................................................................. 4 General overview of Toronto North ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Area Boundaries ........................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Census demographics ................................................................................................................................................................. -

Service Changes Effective Sunday, July 31, 2016 192 Airport Rocket

Service Changes Effective Sunday, July 31, 2016 Earlier Sunday Service: First Vehicles 192 Airport Rocket SB Terminal 3 7:27 NB Kipling Stn 8:00 5 Avenue Road NB Queen's Park 8:15 7 Bathurst SB Steeles 7:37 NB Bathurst Stn 8:06 Service improved to 10' headway from 8:00 11 Bayview SB Steeles 7:30 9 Bellamy SB STC 7:30 NB Warden Stn 8:00 17 Birchmount SB Steeles 7:36 NB Warden Stn 7:48 49 Bloor West EB Markland 7:30 WB Kipling Stn 7:50 21 Brimley SB Steeles 7:21 8 Broadview WB Coxwell 7:45 EB Broadview Stn 8:00 120 Calvington EB Sheppard/Northover 7:37 WB Wilson Stn 8:00 126 Christie NB Christie Stn 7:48 WB St. Clair W Stn 8:00 20 Cliffside WB Kennedy Stn 7:28 EB Main Stn 7:28 87 Cosburn EB Broadview Stn 7:37 WB Main Stn 7:33 113 Danforth EB Main Stn 7:37 WB Kennedy Stn 8:03 127 Davenport EB Townsley Loop 7:32 WB Spadina Stn 7:55 23 Dawes SB St. Clair 7:48 NB Main Stn 8:00 108B Downsview/Arleta EB Jane/Driftwood 7:45 WB Downsview Stn 8:05 108A Downsview/Grandravine EB Jane/Driftwood 8:05 WB Downsview Stn 8:15 101 Downsview Park WB Downsview Stn 8:00 EB Downsview Park 8:10 125 Drewry EB Torresdale/Antibes 7:44 WB Finch Stn 8:00 29 Dufferin Service improved to 10' headway from 8:10 105 Dufferin N SB Rutherford 7:31 NB Downsview 8:00 111 East Mall SB Martin Grove/Eglinton 7:37 NB Kipling Stn 7:54 32C Eglinton W/Trethewey SB Pine/Lawrence 7:42 Service improved to 10' headway from 8:00 32A Eglinton West/Renforth Service improved to 10' headway from 8:00 15 Evans EB Sherway Gardens 7:29 SB Royal York Stn 7:37 104 Faywood SB Downsview Stn 7:45 -

Toronto's Natural Environment Trail Strategy

Natural Environment Trail Strategy June 2013 City of Toronto Prepared by LEES+AssociatesLandscape Architects and Planners with ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The City of Toronto’s Natural Environment Trail Strategy is a product of over fifteen years of cumulative trail management experiences, outreach, stewardship and efforts by many groups and individuals. We would like to thank the following people who helped create, shape and inform the strategy in 2012: Natural Environment Trails Program Working Group Garth Armour Jennifer Kowalski Rob Mungham Michael Bender Scott Laver Brittany Reid Edward Fearon Roger Macklin Alex Shevchuk Norman DeFraeye Beth Mcewen Karen Sun Ruthanne Henry Brian Mercer Ed Waltos Natural Environment Trails Program Advisory Team Lorene Bodiam Jennifer Hyland Jane Scarffe Christina Bouchard Dennis Kovacsi William Snodgrass Susanne Burkhardt Sibel Sarper Jane Weninger Susan Hughes City of Toronto Teresa Bosco Jennifer Gibb Wendy Strickland Jack Brown Jim Hart Richard Ubbens Chris Clarke Janette Harvey Mike Voelker Chris Coltas Amy Lang Soraya Walker Jason Doyle Nancy Lowes Cara Webster Carlos Duran Cheryl Post Sean Wheldrake Jason Foss Kim Statham Alice Wong Councillor Mary Fragedakis Christine Speelman Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Adele Freeman Alexis Wood Adam Szaflarski Amy Thurston Keri McMahon Vince D’Elia Arlen Leeming Steven Joudrey Susan Robertson Natural Environment Trail Strategy Project Team Lees+Associates Azimuth Decarto Sustainable Trails The Planning Environmental Consulting, Ltd. Ltd. Partnership consulting, -

2021 Toronto Arts Council Animating Toronto Parks Guidelines

ANIMATING TORONTO PARKS 2021 PROGRAM GUIDELINES Application Deadline: December 7, 2021 TAC is committed to equity and inclusion and welcomes applications from diverse cultural and geographic communities within the City of Toronto. Specific equity measures or targeted programs are in place to ensure full access and participation by Indigenous artists, artists of colour, artists who are Deaf, have disabilities or are living with mental illness, artists who self-identify as 2SLGBTQIAP, newcomer and refugee artists, young and emerging artists and artists working outside the downtown core. Learn more about what we are doing to make TAC more accessible and inclusive in our Equity Framework What does this program support? The Animating Toronto Parks grants program provides funding to professional artists, arts organizations and artist collectives to create and present free arts programming in selected Toronto parks located in Etobicoke, East York, York, North York and Scarborough. For the purposes of this program, “arts programming” may include the presentation of dance, literary arts, music, theatre, visual and media arts, community-engaged arts, Indigenous arts, and other fields of artistic practice. Animating Toronto Parks is a Strategic Funding Program managed by Toronto Arts Council (TAC), in partnership with Toronto Arts Foundation’s *Arts in the Parks initiative, City of Toronto Arts & Culture Services, Parks, Forestry and Recreation (PF&R), Black Creek Community Farm, and community partner Park People. The maximum grant in this program is $25,000. Grants awarded may be less than the full amount requested. Applicants are not required to secure other sources of funding. The payment of artists’ fees is a requirement of this program.