Progress Toward Poliomyelitis Eradication — Nigeria, January–December 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

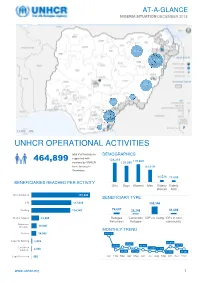

Unhcr Operational Activities 464,899

AT-A-GLANCE NIGERIA SITUATION DECEMBER 2018 28,280 388,208 20,163 1,770 4,985 18.212 177 Bénéficiaires Reached UNHCR OPERATIONAL ACTIVITIES total # of individuals DEMOGRAPHICS supported with 464,899 128,318 119,669 services by UNHCR 109,080 from January to 81,619 December; 34,825 of them from Mar-Apr 14,526 11,688 2018 BENEFICIARIES REACHED PER ACTIVITY Girls Boys Women Men Elderly Elderly Women Men Documentation 172,800 BENEFICIARY TYPE CRI 117,838 308,346 Profiling 114,747 76,607 28,248 51,698 Shelter Support 22,905 Refugee Cameroon IDPs in Camp IDPs in host Returnees Refugee community Awareness Raising 16,000 MONTHLY TREND Referral 14,956 140,116 Capacity Building 2,939 49,819 39,694 24,760 25,441 34,711 Livelihood 11,490 11,158 Support 2,048 46,139 37,118 13,770 30,683 Legal Protection 666 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec www.unhcr.org 1 NIGERIA SITUATION AT-A-GLANCE / DEC 2018 CORE UNHCR INTERVENTIONS IN NIGERIA UNHCR Nigeria strategy is based on the premise that the government of Nigeria assumes the primary responsibility to provide protection and assistance to persons of concern. By building and reinforcing self-protection mechanisms, UNHCR empowers persons of concern to claim their rights and to participate in decision-making, including with national and local authorities, and with humanitarian actors. The overall aim of UNHCR Nigeria interventions is to prioritize and address the most serious human rights violations, including the right to life and security of persons. -

IOM Nigeria DTM Emergency Tracking Tool (ETT) Report No.78 (1-7

DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX - Nigeria DTM Nigeria EMERGENCY TRACKING TOOL (ETT) DTM Emergency Tracking Tool (ETT) is deployed to track and provide up-to-date information on sudden displacement and other population movements ETT Report: No. 78 1 – 7 August 2018 Movements New Arrival Screening by Nutri�on Partners Chad Niger Abadam Arrivals: Children (6-59 months) Lake Chad screened for malnutri�on 5,317 individuals 588 Mobbar Kukawa MUAC category of screened children 71 Departures: 72 Green: 329 Yellow: 115 Red: 144 Guzamala 28 1,177 individuals 770 Gubio Within the period of 1 – 7 August 2018, a total of 6,494 movements were Monguno Nganzai recorded, including 5,317 arrivals and 1,177 departures at loca�ons in 360 827 Marte Askira/Uba, Bama, Chibok, Damboa, Demsa, Dikwa, Fufore, Girei, Gombi, Magumeri Ngala 174 157 Kala/Balge Guzamala, Gwoza, Hawul, Hong, Kala/Balge, Konduga, Kukawa, Madagali, Mafa, Mafa Magumeri, Maiduguri, Maiha, Mayo-Belwa, Michika, Mobbar, Monguno, Jere Dikwa 9 366 11 Borno 12 Mubi-North, Mubi-South, Ngala, Nganzai, Numan, Yola-North and Yola-South Maiduguri Kaga Bama Local Government Areas (LGAs) of Adamawa and Borno States. Konduga 51 928 Assessments iden�fied the following main triggers of movements: ongoing Gwoza conflict (45%), poor living condi�ons (24%), voluntary reloca�on (9%), improved 532 security (7%), military opera�ons (6%), involuntary reloca�on (4%), fear of Damboa 7 a�acks/communal clashes (4%), and farming ac�vi�es (1%). 20 Madagali Biu Chibok Askira/Uba 179 Number of individuals by movement triggers -

Pdf | 323.79 Kb

Borno State Nigeria Emergency Response Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) W21 2021 (May 24-May 30) Table of Contents A. Key indicators B. Indicator-based surveillance C. System performance A. Key indicators Surveillance | Performance Indicators 25 25 277 221 79% 75% Number of Number of LGAs Number of health Number of health Completeness Timeliness LGAs* that reported facilities facilities that at health facility at health facility reported level. 92% at LGA level. 88% at LGA level. level. Alert | W21 Alert | Risk Assessment 68 93% 0 W21 Cumulative Total alerts % alerts verified # alerts requiring 0 19 Low risk raised** response 0 18 Moderate risk * The reporting of health facility level IDSR data is currently being rolled out across Borno State. Whilst this is taking place, some LGAs are continuing to report only at the level of local government area (LGA). Therefore, completenss and timeliness of reporting is displayed at both levels in this bulletin. 0 22 High risk ** Alerts are based on 7 weekly reportable diseases in the national IDSR reporting format (IDSR 002) and 8 additional diseases/health events of public health importance 0 1 Very high risk in the IDP camps and IDP hosting areas. Figure 1 | Trend in consultations 100000 75000 50000 Number 25000 0 W52 2016 W26 2017 W01 2018 W26 2018 W01 2019 W27 2019 W01 2020 W27 2020 W53 2020 New visits Repeat visits B. Indicator-based surveillance Summary Figure 1a | Proportional morbidity (W21) Figure 1b | Proportional mortality (W21) Malaria (confirmed) Severe Acute Malnutrition -

Ngala Idp Camp

QUICK ASSESSMENT: NGALA IDP CAMP SIF / NIGERIA Date of the mission: 13th December, 2016. Location: Ngala IDP Camp (Ngala LGA, Borno State, North-East Nigeria) Coordinates a. Military HQ (3rd battalion): 12°21'28.68"N 14°10'49.60"E A: 291m b. Helipad: 12°21'24.70"N 14°10'42.40"E A: 292m c. IDP camp: 12°21'34.87"N 14°10'19.57"E A: 288m Ngala IDP Camp Quick Assessment Page 1/9 Security and logistics (source: SIF and UN Joint Security Assessment) Ngala has been liberated by NAF on March 2016. Fighting against insurgents has been ongoing until summer 2016. The road and the border are now open and UNHAS helicopters are currently serving Ngala since December 2016. LGA level: On June, a clearance operation has been conducted by 3rd Battalion from Ngala towards North of the LGA, along the Cameroonian border to push away insurgents groups present in this zone of Ngala LGA. This LGA is part of the Area of Operations of Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP). This group remains active in the North of Ngala – due to the presence of bases in Lake Chad area – and in Kala Balge LGA where it has a freedom of movement in the southern part of the LGA. ISWAP groups are very mobile and base their actions on guerrilla warfare (ambushes, IED’s, hit- and-run tactic). Skirmishes with NAF can occur during the patrols. The actual NAF deployment is centered on: The control of the road Dikwa – Ngala to keep it open for commercial convoys, The control of the LGA’s Headquarters, The capability to conduct combat patrols from bases in order to conduct a zone control deeply inside the LGA’s. -

FEWS NET Special Report: a Famine Likely Occurred in Bama LGA and May Be Ongoing in Inaccessible Areas of Borno State

December 13, 2016 A Famine likely occurred in Bama LGA and may be ongoing in inaccessible areas of Borno State This report summarizes an IPC-compatible analysis of Local Government Areas (LGAs) and select IDP concentrations in Borno State, Nigeria. The conclusions of this report have been endorsed by the IPC’s Emergency Review Committee. This analysis follows a July 2016 multi-agency alert, which warned of Famine, and builds off of the October 2016 Cadre Harmonisé analysis, which concluded that additional, more detailed analysis of Borno was needed given the elevated risk of Famine. KEY MESSAGES A Famine likely occurred in Bama and Banki towns during 2016, and in surrounding rural areas where conditions are likely to have been similar, or worse. Although this conclusion cannot be fully verified, a preponderance of the available evidence, including a representative mortality survey, suggests that Famine (IPC Phase 5) occurred in Bama LGA during 2016, when the vast majority of the LGA’s remaining population was concentrated in Bama Town and Banki Town. Analysis indicates that at least 2,000 Famine-related deaths may have occurred in Bama LGA between January and September, many of them young children. Famine may have also occurred in other parts of Borno State that were inaccessible during 2016, but not enough data is available to make this determination. While assistance has improved conditions in accessible areas of Borno State, a Famine may be ongoing in inaccessible areas where conditions could be similar to those observed in Bama LGA earlier this year. Significant assistance in Bama Town (since July) and in Banki Town (since August/September) has contributed to a reduction in mortality and the prevalence of acute malnutrition, though these improvements are tenuous and depend on the continued delivery of assistance. -

NGALA LGA, BORNO STATE (December, 2018) Working Group - Nigeria

Child Protec�on Sub CHILD PROTECTION REFERRAL DIRECTORY - NGALA LGA, BORNO STATE (December, 2018) Working Group - Nigeria NGALA - click to view online CHILD PROTECTION SERVICES PROVIDED ON SITE Service Provider Contact Informa�on Badairi Lake Chad ± Zaga Ngalori Kirenowa Cameroon FHI 360 INTERSOS AIPD CHAD/UNICEF Borsori Wulgo Priscilla Mamza Shukurat M Lawal Grace Mark Fredrick Otherniel Marte Shehuri Case MGT (07037563344) (08060535344) (08101512636) (07068179064) Gamboru B Gamboru A Marte Gamboru C Muwalli Ngala Rann - Case Management Case Management Case Management - Family Tracing Njine Fuye Musune Sigal of UASC and of UASC and and Reunifica�on A Lawant Moholo Ngala - Alternative Care Children at Risk Children at Risk - Alterna�ve Care Gumna Logumane K Kumaga Ala Ndufu Kala/Balge Gajibo Mujigine Niger Kala Lake Chad Chad Mafa Dikwa Warshele Ngudoram Dikwa Borno Nigeria M. Kaza Ufaye M. Maja Jarawa Gawa Boboshe Mada CameroonK Kaudi Afuye FHI 360 IOM CHAD/UNICEF UNICEF POPULATION INFORMATION Haruna Samuel Samuel Akahoemi Fredrick Otherniel Pwaluk luku PSS (09029551950) (07062325233) (7068179064) (08161720289) Number of IDPs: 61,082 - Life Skills for - Life Skills for Adolescents Mental Health Adolescents Recrea�onal Support - Recrea�onal IDP Households: - Recrea�onal Ac�vi�es 14,295 Ac�vi�es Ac�vi�es Girls: 18,813 Boys: 15,393 IOM Ali Umar SER (07068910000) Women: 14,785 Men: 12,091 COMMITMENTS CP CORE Livelihoods Source: Nigeria DTM Round 25 VULNERABILITIES Unaccompanied Children: 86 DRC/DDG /UNICEF MAG/UNICEF Separated Children: 366 -

North-East Nigeria January 2021

OPERATIONAL UPDATE North-East Nigeria January 2021 Over 6,100 men, women and UNHCR’s protection, human rights and UNHCR and partners raised children were newly border monitoring teams reached nearly awareness about COVID-19 and displaced in Borno, 33,000 internally displaced people and protection among over 22,000 Adamawa and Yobe States refugee returnees in Borno, Adamawa and people in the BAY States in in January. Yobe (BAY) States. January 2021. A UNHCR protection partner colleague conducts a rapid protection assessment with internally displaced people in Bama, Borno State. © UNHCR/Daniel Bisu www.unhcr.or g 1 NORTH-EAST NIGERIA OPERATIONAL UPDATE JANUARY 2021 Operational Highlights ■ The security situation in the North-East remains unpredictable. The operational area continues to be impacted by the ongoing violent conflict, terrorism, and criminal activities, which have resulted in the displacement, killing and abduction of civilians as well as the destruction of properties and critical infrastructure. The second wave of COVID-19 also continues to exacerbate the already worsening situation. A total of 43 security incidents perpetrated by NSAG in the BAY States comprised of attacks on civilians, improvised explosive devices, and attacks on security forces. ■ In Borno State, members of the non-State armed groups (NSAGs) continued their attacks on both civilian and military targets, attempted to overrun of villages and towns and mounted illegal vehicle checkpoints for the purpose of abduction, looting and robbery. The main supply routes Maiduguri- Gubio, Maiduguri-Mafa and Mungono-Ngala in the Northern axis were most severely hit. The situation along the Maiduguri-Damaturu road, a main supply route, worsened further in January, forcing the reclassification of the route from the hitherto “Restricted” to “No go” for humanitarian staff and cargo. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT FEBRUARY 13, 2019 S/N Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 4 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 5 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 6 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 7 Above Only Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Benson Idahosa University Campus, Ugbor GRA, Benin EDO Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank 8 Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi BAUCHI 9 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 10 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 11 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 12 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 13 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 14 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. Area, Nasarawa State NASSARAWA 15 Adazi-Enu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Nkwor Market Square, Adazi- Enu, Anaocha Local Govt, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 16 Adazi-Nnukwu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Near Eke Market, Adazi Nnukwu, Adazi, Anambra State ANAMBRA 17 Addosser Microfinance Bank Limited State 32, Lewis Street, Lagos Island, Lagos State LAGOS 18 Adeyemi College Staff Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Adeyemi College of Education Staff Ni 1, CMS Ltd Secretariat, Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo ONDO 19 Afekhafe Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit No. -

RIGSS: Field Summary Maiduguri and Borno State

We gratefully acknowledge the support of: RIGSS: Field Summary • RUWASA Maiduguri, Borno State • Manual drillers association Maiduguri and Borno State • Unimaid Radio and Peace FM INTRODUCTION METHODOLOGY Water security is one of the most pressing risks facing the world. In rapidly The Maiduguri field study involved two main activities: growing urban areas, evidence suggests that increasing numbers of • Detailed water point surveys of 14 groundwater sources, including households are choosing to install private boreholes to meet their domestic vulnerability and water quality assessments, plus additional water quality water needs. The RIGSS project used an innovative interdisciplinary sampling at a further 14 sources approach to understand the environmental, social, behavioural and institutional reasons for this trend, and its potential implications for individual • Qualitative interviews and focus groups to capture the perceptions of and community resilience. community and household water users The following groundwater sources were examined in Maiduguri: STUDY AREA • 21 motorised boreholes, nine of which were sampled after storage in a The study was carried out in the city of Maiduguri, which sits across two Local tank Government Areas (LGA): Maiduguri and neighbouring Konduga, in Borno • 7 hand pump boreholes State, north eastern Nigeria. At the 14 sources subjected to a detailed water point survey, ten were privately owned (all motorized boreholes) and four were developed by NGOs for IDP camps (2 motorised boreholes and 2 hand pump -

Fact Sheet: Ngala Local Government Area Borno State, North-East Nigeria Last Updated May 2020

Fact Sheet: Ngala Local Government Area Borno State, North-east Nigeria Last updated May 2020 68,058 34,713 15,347 12,558 3,396 2,044 3 Infants Elderly Children Women Men IDP Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) Camps Overview • Ngala Local Government Area (LGA), located in eastern Borno State on the border with Cameroon and the Lake Chad. • The occupation by non-state armed groups (NSAGs) triggered a massive displacement of the population, including the alleged killing of over 300 civilians and destruction of public and private property. • Access into the town is by air through UNHAS or by road with a military escort at least twice a week on the main routes out of Ngala town including the Maiduguri-Ngala road and the Ngala-Rann road. • According to IOM DTM, over 800 IDPs households arrived in Ngala LGA between January 2020 to March 2020 with more than half living in dire conditions at the Arabic camp reception centre. • COVID-19: An extensive risk communication awareness campaign on individual precautionary measures against COVID-19 is being implemented, amplified through religious organizations, local communities, social and traditional media. • COVID-19: Humanitarian response efforts focus on preparedness, surveillance, risk communication, and adjusting modalities to ensure operational continuity to minimize the impact of COVID-19 on vulnerable communities and humanitarian partners. November 2016 January 2017 August 2017 December 2018 January 2019 5 March 2019 NSAG attacked SF positions ICRC and WFP Ngala LGA witnessed a Hepatitis E outbreak There was an attack, There was another around Logomani and Mbiu conducted the first high influx of new spread through Ngala LGA. -

Monthly Factsheet *Response Analysis from January - June 2019 5W Data Collection June 2019

Monthly Factsheet *Response analysis from January - June 2019 5W data collection June 2019 Abadam Yusufari Yunusari Machina Mobbar Kukawa Lake Chad Nguru Karasuwa Guzamala Bade Bursari Geidam Gubio Bade Monguno Nganzai Jakusko 721,268 Marte Tarmua Ngala Magumeri Mafa Kala/Balge Yobe Jere Fune Dikwa Nangere Damaturu Borno Maiduguri Potiskum 145 Kaga Konduga Bama PICTURE Fika Gujba Gwoza Damboa 111,445 Gulani Chibok Biu Madagali Askira/Uba Kwaya Michika Kusar Hawul Mubi Bayo Hong North Beneficiaries Shani Gombi Mubi South 224,266 Maiha Photo Credit: Kolawole Girls Makeshift/ selfmade shelters, Shuwari 5 camp, Maiduguri, Borno. Adewale (OCHA) 36,138 Guyuk Song Shelleng 11,098 Lamurde 183,505 Girei Boys 29,822 Numan Demsa Yola 2019 Response Highlights Yola South North Mayo-Belwa Shelter Interventions 22,612 households have received emergency shelter solutions while 4,385 167,244 Fufore Women 25,194 households received reinforced/transitional shelter solutions. 5,140 Non-food Item interventions Jada DMS/CCCM Activities 23,346 households reached through improved, basic and complimentary NFI Men 134,102 20,010 Lake Chad Ganye kits. Inaccessible Areas 23,249 Elderly Shelter NFI Beneficiaries 76,031 eligible individuals biometrically registered since January 2019. 5,566 Adamawa Toungo CCCM Beneficiaries ESNFI & CCCM activity 1,500 households reached through Cash/Voucher for Shelter support. No Activity June 2019 Summary - Arrival Movements 1,305 CCCM Shelter/NFI 1,149 10,153 3,753 Arrivals Departures 897 869 737 730 *graph shows only arrivals of more -

Download Download

Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography Volume 2 1997 FOREIGN PERIODICALS ON AFRICA Foreign Periodicals on Africa John Bruce Howell∗ ∗University of Iowa Copyright c 1997 by the authors. Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography is produced by Iowa Research Online. http://ir.uiowa.edu/ejab/vol2/iss1/1 Volume 2 (1997) Foreign Periodicals on Africa John Bruce Howell, International Studies Bibliographer, University of Iowa Libraries Contents 1. Abia State (Nigeria) Approved estimates of Abia State of Nigeria. -- Umuahia: Govt. Printer,(Official document) 1992, 1993 (AGR5306) 2. Abia State (Nigeria) Authorised establishments of Abia state civil service...fiscal year: special analysis of personnel costs. -- Umuahia, Abia State, <Nigeria>: Burueau of Budget and Planning, Office of the Governor. 1992 (AGR5299) 3. Abinibi. Began with Nov. 1986 issue. -- Lagos: Lagos State Council for Arts and Culture, v. 2: no.1-4, v.4:no.1 (AGD3355) 4. Aboyade, Ojetunji. Selective closure in African economic relations / by Ojetunji Aboyade. -- Lagos: Nigerian Institute of International Affairs, 1991. (Lecture series, 0331-6262; no. 69) (AGN9665) 5. Abubakar, Ayuba T. Planning in strategic management. -- Topo, Badagry: ASCON Publications, 1992. (Occasional papers / Administrative Staff College of Nigeria; 5.) (AGN9807) 6. Academie malgache. Bulletin. v. 1-12, 1902-13; new ser., t.1- 1914- -- Tananarive. (AGD1928) 7. Academie malgache. Bulletin d'information et de liaison / Academie malgache. -- Antananarivo: L'Academie,. v. 5, 7-10, 12, 16-17, 19 (AGD2020) 8. ACMS staff papers / Association of African Central Banks. Began in 1988? -- Dakar, Senegal: The Association, v.1:no. 4., no.5 (AGK8604) 9. Actualites Tchadiennes. -- <N'Djamena>: Direction de la presse a la presidence de la republique.