Education and Boko Haram in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISIS in Africa: Implications from Syria and Iraq Dr

ISIS in Africa: Implications from Syria and Iraq Dr. Joseph Siegle28 Africa Center for Strategic Studies National Defense University At the end of 2016, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, leader of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), announced that the group had “expanded and shifted some of our command, media, and wealth to Africa.” ISIS’s Dabiq magazine referred to the regions of Africa that were part of its “caliphate:” “the region that includes Sudan, Chad and Egypt has been named the caliphate province of Alkinaana; the region that includes Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya and Uganda as the province of Habasha; the North African region encompassing Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Nigeria, Niger and Mauritania as Maghreb, the province of the caliphate.” Leaving aside the mismatched ethno-linguistic groupings included in each of these “provinces,” ISIS’s interest in establishing a presence in Africa has long been a part of its vision for a global caliphate. Battlefield setbacks in ISIS’s strongholds in Iraq and Syria since 2015, however, raise questions of what impact this will have for ISIS’s African aspirations. A useful starting point in considering this question is to recognize that the threat from violent Islamist groups in Africa is not monolithic but is comprised of a variety of distinct entities. For the most part, these groups are geographically concentrated and focused on local territorial or political objectives. Specifically, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies has identified 5 major categories of militant Islamists groups in Africa (see map): http://africacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Africas-Active-Militant-Islamist- Groups-November-2016.pdf. -

Osprey Group Profile

Osprey Group Profile The preferred and trusted partner for international companies seeking to grow their business in West Africa Africa Europe North Africa West Africa East Africa South Africa Head Quarter Africa Head Quarters Europe Osprey House 47 Mississippi Wraysbury Hall Street, Ferry Lane Maitama District, TW196HG Staines, Middlesex Abuja FCT. Nigeria. London, UK. Introduction to Osprey Welcome to Osprey Investments Group, where our mission is to help drive development in West Africa by facilitating inward investment supported by world- class consultancy services delivered by competent technical partners. We achieve this by: • Connecting potential investors to opportunities in Africa and specifically marketing investment opportunities to multi-national firms in Asia, Europe and the US, • Facilitating fair and durable projects between Government and big multinational firms, • Promoting technology and skills transfer to local firms to improve efficiency, raise productivity and boost skilled employment, • Helping multi-national firms understand the risk/return trade-off of investing in Africa, and • Providing our clients with world-class technical resources. We are passionate about West Africa and firmly believe it will become one of the top 20 economies by 2020. With more than 44 years experience of working in Nigeria and a dedicated team of staff based in the capital Abuja, we can help your business gain a strategic foothold in the West African market place. Introduction to ECOWAS Population: 300 million Size: 923,768 sq. km Growth rate: 8.4% (ranked 15th in world) GDP (PPP): $378 billion (ranked 32nd in world) GDP per capita: $2500 GNI: $176 billion Labour force: 50 million Inflation rate: 13.7% Market value of publicly traded shares: $51 billion Largest ethnic groups: Hausa, Igbo, Yoruba Ref: CIA World fact book Why West Africa? West Africa, with an area of over 2.5 million square miles and estimated population of 325.5 million is Size of market comparable in size and people to the continental USA. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: OSUAGWU, Linus Chukwunenye. Status: Professor & Former Vice Chancellor. Specialization: Business Admi

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: OSUAGWU, Linus Chukwunenye. Status: Professor & Former Vice Chancellor. Specialization: Business Administration/Marketing . Nationality: Nigerian. State of Origin: Imo State of Nigeria (Ihitte-Uboma LGA). Marital status: Married (with two children: 23 years; and 9 years). Contact address: School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria,Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria; Tel: +2348033036440; +2349033069657 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Skype ID: linus.osuagwu; Twitter: @LinusOsuagwu Website: www.aun.edu.ng SCHOOLS ATTENDED WITH DATES: 1. Comm. Sec. School, Onicha Uboma, Ihitte/Uboma, Imo State, Nigeria (1975 - 1981). 2. Federal University of Technology Owerri, Nigeria, (1982 - 1987). 3. University of Lagos, Nigeria (1988 - 1989; 1990 - 1997). ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS: PhD Business Administration/Marketing (with Distinction), University of Lagos, Nigeria, (1998). M.Sc. Business Administration/Marketing, University of Lagos, Nigeria, (1990). B.Sc. Tech., Second Class Upper Division, in Management Technology (Maritime), Federal University of Technology Owerri (FUTO), Nigeria (1987). 1 WORKING EXPERIENCE: 1. Vice Chancellor, Eastern Palm University, Ogboko, Imo State, Nigeria (2017-2018). 2. Professor of Marketing, School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria, Yola (May 2008-Date). 3. Professor of Marketing & Chair of Institutional Review Boar (IRB), American University of Nigeria Yola (2008-Date). 4. Professor of Marketing & Dean, School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria, Yola (May 2013-May 2015). 4. Professor of Marketing & Acting Dean, School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria (January 2013-May 2013) . 5. Professor of Marketing & Chair of Business Administration, Department of Business Administration, School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria (2008-2013). 6. -

BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S

112TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE " COMMITTEE PRINT ! 1st Session PRINT 112–B BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S. Homeland SUBCOMMITTEE ON COUNTERTERRORISM AND INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES December 2011 FIRST SESSION U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 71–725 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia LAURA RICHARDSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TIM WALBERG, Michigan BRIAN HIGGINS, New York CHIP CRAVAACK, Minnesota JACKIE SPEIER, California JOE WALSH, Illinois CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania HANSEN CLARKE, Michigan BEN QUAYLE, Arizona WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia KATHLEEN C. HOCHUL, New York BILLY LONG, Missouri VACANCY JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas MO BROOKS, Alabama MICHAEL J. RUSSELL, Staff Director & Chief Counsel KERRY ANN WATKINS, Senior Policy Director MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director (II) C O N T E N T S BOKO HARAM EMERGING THREAT TO THE U.S. HOMELAND I. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 II. Findings .............................................................................................................. -

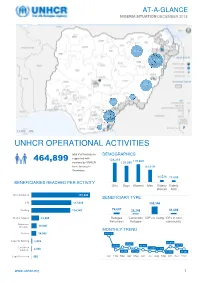

Unhcr Operational Activities 464,899

AT-A-GLANCE NIGERIA SITUATION DECEMBER 2018 28,280 388,208 20,163 1,770 4,985 18.212 177 Bénéficiaires Reached UNHCR OPERATIONAL ACTIVITIES total # of individuals DEMOGRAPHICS supported with 464,899 128,318 119,669 services by UNHCR 109,080 from January to 81,619 December; 34,825 of them from Mar-Apr 14,526 11,688 2018 BENEFICIARIES REACHED PER ACTIVITY Girls Boys Women Men Elderly Elderly Women Men Documentation 172,800 BENEFICIARY TYPE CRI 117,838 308,346 Profiling 114,747 76,607 28,248 51,698 Shelter Support 22,905 Refugee Cameroon IDPs in Camp IDPs in host Returnees Refugee community Awareness Raising 16,000 MONTHLY TREND Referral 14,956 140,116 Capacity Building 2,939 49,819 39,694 24,760 25,441 34,711 Livelihood 11,490 11,158 Support 2,048 46,139 37,118 13,770 30,683 Legal Protection 666 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec www.unhcr.org 1 NIGERIA SITUATION AT-A-GLANCE / DEC 2018 CORE UNHCR INTERVENTIONS IN NIGERIA UNHCR Nigeria strategy is based on the premise that the government of Nigeria assumes the primary responsibility to provide protection and assistance to persons of concern. By building and reinforcing self-protection mechanisms, UNHCR empowers persons of concern to claim their rights and to participate in decision-making, including with national and local authorities, and with humanitarian actors. The overall aim of UNHCR Nigeria interventions is to prioritize and address the most serious human rights violations, including the right to life and security of persons. -

The Concepts of Al-Halal and Al-Haram in the Arab-Muslim Culture: a Translational and Lexicographical Study

The concepts of al-halal and al-haram in the Arab-Muslim culture: a translational and lexicographical study NADER AL JALLAD University of Jordan 1. Introduction This paper1 aims at providing sufficient definitions of the concepts of al-Halal and al-Haram in the Arab-Muslim culture, illustrating how they are treated in some bilingual Arabic-English dictionaries since they often tend to be provided with inaccurate, lacking and sometimes simply incorrect definitions. Moreover, the paper investigates how these concepts are linguistically reflected through proverbs, collocations, frequent expressions, and connota- tions. These concepts are deeply rooted in the Arab-Muslim tradition and history, affecting the Arabs’ way of thinking and acting. Therefore, accurate definitions of these concepts may help understand the Arab-Muslim identity that is vaguely or poorly understood by non-speakers of Arabic. Furthermore, to non-speakers of Arabic, these notions are often misunderstood, inade- quately explained, and inaccurately translated into other languages. 2. Background and Methodology The present paper is in line with the theoretical framework, emphasizing the complex relationship between language and culture, illustrating the importance of investigating linguistic data to understand the Arab-Muslim vision of the world. Linguists like Boas, Sapir and Whorf have extensively studied the multifaceted relationship between language and culture. Other examples are Hoosain (1991), Lucy (1992), Gumperz y Levinson (1996), 1 This article is part of the linguistic-cultural research done by the research group HUM-422 of the Junta de Andalucía and the Research Group of Experimental and Typological Linguistics (HUM0422) of the Junta de Andalucía and the Project of Quality Research of the Junta de Andalucia P06-HUM-02199 Language Design 10 (2008: 77-86) 78 Nader al Jallad Luque Durán (2007, 2006a, 2006b), Pamies (2007, 2008) and Luque Nadal (2007, 2008). -

Violence in Nigeria's North West

Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem Africa Report N°288 | 18 May 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Community Conflicts, Criminal Gangs and Jihadists ...................................................... 5 A. Farmers and Vigilantes versus Herders and Bandits ................................................ 6 B. Criminal Violence ...................................................................................................... 9 C. Jihadist Violence ........................................................................................................ 11 III. Effects of Violence ............................................................................................................ 15 A. Humanitarian and Social Impact .............................................................................. 15 B. Economic Impact ....................................................................................................... 16 C. Impact on Overall National Security ......................................................................... 17 IV. ISWAP, the North West and -

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’S Enduring Insurgency

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Editor: Jacob Zenn Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Jacob Zenn (Editor) Abdulbasit Kassim Elizabeth Pearson Atta Barkindo Idayat Hassan Zacharias Pieri Omar Mahmoud Combating Terrorism Center at West Point United States Military Academy www.ctc.usma.edu The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, United States Military Academy, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government. May 2018 Cover Photo: A group of Boko Haram fighters line up in this still taken from a propaganda video dated March 31, 2016. COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Director The editor thanks colleagues at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point (CTC), all of whom supported this endeavor by proposing the idea to carry out a LTC Bryan Price, Ph.D. report on Boko Haram and working with the editor and contributors to see the Deputy Director project to its rightful end. In this regard, I thank especially Brian Dodwell, Dan- iel Milton, Jason Warner, Kristina Hummel, and Larisa Baste, who all directly Brian Dodwell collaborated on the report. I also thank the two peer reviewers, Brandon Kend- hammer and Matthew Page, for their input and valuable feedback without which Research Director we could not have completed this project up to such a high standard. There were Dr. Daniel Milton numerous other leaders and experts at the CTC who assisted with this project behind-the-scenes, and I thank them, too. Distinguished Chair Most importantly, we would like to dedicate this volume to all those whose lives LTG (Ret) Dell Dailey have been afected by conflict and to those who have devoted their lives to seeking Class of 1987 Senior Fellow peace and justice. -

Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping up Recovery: US-Lake Chad Region 2013-2016

From Pariah to Partner: The US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma, 2009 to 2015 Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping Up Recovery Making Peace Possible US Engagement in the Lake Chad Region 2301 Constitution Avenue NW 2013 to 2016 Washington, DC 20037 202.457.1700 Beth Ellen Cole, Alexa Courtney, www.USIP.org Making Peace Possible Erica Kaster, and Noah Sheinbaum @usip 2 Looking for Justice ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This case study is the product of an extensive nine- month study that included a detailed literature review, stakeholder consultations in and outside of government, workshops, and a senior validation session. The project team is humbled by the commitment and sacrifices made by the men and women who serve the United States and its interests at home and abroad in some of the most challenging environments imaginable, furthering the national security objectives discussed herein. This project owes a significant debt of gratitude to all those who contributed to the case study process by recommending literature, participating in workshops, sharing reflections in interviews, and offering feedback on drafts of this docu- ment. The stories and lessons described in this document are dedicated to them. Thank you to the leadership of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and its Center for Applied Conflict Transformation for supporting this study. Special thanks also to the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Transition Initiatives (USAID/OTI) for assisting with the production of various maps and graphics within this report. Any errors or omis- sions are the responsibility of the authors alone. ABOUT THE AUTHORS This case study was produced by a team led by Beth ABOUT THE INSTITUTE Ellen Cole, special adviser for violent extremism, conflict, and fragility at USIP, with Alexa Courtney, Erica Kaster, The United States Institute of Peace is an independent, nonpartisan and Noah Sheinbaum of Frontier Design Group. -

Lessons from Colombia for Curtailing the Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria

Lessons From Colombia For Curtailing The Boko Haram Insurgency In Nigeria BY AFEIKHENA JEROME igeria is a highly complex and ethnically diverse country, with over 400 ethnic groups. This diversity is played out in the way the country is bifurcated along the lines of reli- Ngion, language, culture, ethnicity and regional identity. The population of about 178.5 million people in 2014 is made up of Christians and Muslims in equal measures of about 50 percent each, but including many who embrace traditional religions as well. The country has continued to experience serious and violent ethno-communal conflicts since independence in 1960, including the bloody and deadly thirty month fratricidal Civil War (also known as the Nigerian-Biafran war, 1967-70) when the eastern region of Biafra declared its seces- sion and which claimed more than one million lives. The most prominent of these conflicts recently pitch Muslims against Christians in a dangerous convergence of religion, ethnicity and politics. The first and most dramatic eruption in a series of recent religious disturbances was the Maitatsine uprising in Kano in December 1980, in which about 4,177 died. While the exact number of conflicts in Nigeria is unknown, because of a lack of reliable sta- tistical data, it is estimated that about 40 percent of all conflicts have taken place since the coun- try’s return to civilian rule in 1999.1 The increasing wave of violent conflicts across Nigeria under the current democratic regime is no doubt partly a direct consequence of the activities of ethno- communal groups seeking self-determination in their “homelands,” and of their surrogate ethnic militias that have assumed prominence since the last quarter of 2000. -

Quality of University Education in Nigeria: the Challenge of Social Relevance

Quality of University Education in Nigeria: The Challenge of Social Relevance Convocation Lecture at the 22nd and 23rd Combined Convocation Ceremony University of Uyo, Nigeria Friday, 3 November, 2017 Olugbemiro Jegede Emeritus Professor National Open University of Nigeria OJ Jegede: UNIUYO 2017 Convocation Lecture 1 Table of Contents Section Page 1.0 Preamble 3 2.0 More Congratulations and Commendation to the University of Uyo 8 3.0 The Foci and the Goals of the Lecture 12 4.0 Hello, UNIUYO Graduands 13 5.0 Introduction 17 6.0 Our Nostalgic Past 18 7.0 Quality? What Quality? 18 8.0 Education and Development 21 9.0 Nigeria’s Vital Educational Statistics 22 10.0 In The Beginning… 24 11.0 The Establishment of Fully Fledged Universities in Africa 28 12.0 Higher Education in Nigeria 31 13.0 Origin, Size and Shape of the Nigerian University System 33 14.0 Funding 37 15.0 When and How Things Began to Fall Apart 38 16.0 The Collapse of the Educational System 43 17.0 Urgently Required: Declare Education a Disaster Area Needing Emergency Rescue 46 18.0 Solutions/Way Forward 48 19.0 What Must Nigeria Do To Stem the Tide 49 19.1 Change at the Level of the Nigerian State 50 19.2 Change Through the Organised Private Sector 58 19.3 Change Through the Universities 62 19.4 Change Through the Academia and the Academics 66 19.5 Change Through Parents and Home 73 20.0 Conclusion 76 References 83 OJ Jegede: UNIUYO 2017 Convocation Lecture 2 1.0 Preamble 1.1 The Visitor of this University, The President & Commander in Chief of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, -

Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence

Terrorism and Political Violence ISSN: 0954-6553 (Print) 1556-1836 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ftpv20 Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence Seung-Whan Choi & Benjamin Acosta To cite this article: Seung-Whan Choi & Benjamin Acosta (2018): Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence, Terrorism and Political Violence, DOI: 10.1080/09546553.2018.1472585 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1472585 Published online: 13 Jun 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ftpv20 TERRORISM AND POLITICAL VIOLENCE https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1472585 Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence Seung-Whan Choi c and Benjamin Acosta a,b aInterdisciplinary Center Herzliya, Herzliya, Israel; bInternational Institute for Counter-Terrorism, Herzliya, Israel; cPolitical Science, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA ABSTRACT KEY WORDS Although fundamentalist Sunni Muslims have committed more than Suicide attacks; sectarian 85% of all suicide attacks, empirical research has yet to examine how violence; Sunni militants; internal sectarian conflicts in the Islamic world have fueled the most jihad; internal conflict dangerous form of political violence. We contend that fundamentalist Sunni Muslims employ suicide attacks as a political tool in sectarian violence and this targeting dynamic marks a central facet of the phenomenon today. We conduct a large-n analysis, evaluating an original dataset of 6,224 suicide attacks during the period of 1980 through 2016. A series of logistic regression analyses at the incidence level shows that, ceteris paribus, sectarian violence between Sunni Muslims and non-Sunni Muslims emerges as a substantive, signifi- cant, and positive predictor of suicide attacks.