Van Panchayats in Three Villages: Dependency and Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Wise

DISTRICT WISE Name, Address & Mobile Nos. of Trained Para-Legal Volunteers (PLVs) & Name of Village Legal Care & Support Centres (VLCs) ALMORA S.N. Name of VLC Name of the PLV Address Mobile No. 1. Bhikiyasen 1. Sh. Lalit Nath S/o Late Sh. Prem Nath, R/o Village, 8006570590 PO & Tehsil –Bhikiyasen District-Almora 2. Smt. Anita Bisht W/o Late Deependra Singh Bisht 9410971555 R/o Village, P.O. & Tehsil – Bhikiyasen, District – Almora 3. Sh. Manoj Kumar S/o Sh. Devendra Prakash R/o 09760864888 Village-Saboli Rautela, P.O. & Tehsil- Bhikiyasen, District-Almora 4. Sh. Vinod Kumar S/o Sh. Durga Dutt, Village-Kaulani, 9675315130 P.O.-Upradi, Tehsil-Syelde, Almora 2. Salt 1. Sh. Ramesh Chandra Bhatt S/o Sh. Bhola Dutt Bhatt 9639582757 Village & PO- Chhimar Tehsil-Salt, District-Almora 2. Sh. Haridarshan S. Rawat S/o Sh. Sadhav Singh 9627784944 & Village-Nandauli, PO-Thalamanral 9411703361 Tehsil-Salt, District Almora 3. Chaukhutia 1. Smt. Kavita Devi W/o Sh. Kuber Singh 9720608681 Village-Chandikhet 9761152808 PO – Ganai, District-Almora 2. Sh. Lalit Mohan Bisht S/o Sh. Gopal Singh 9997626408 & Village, PO & Tehsil–Chaukhutiya 9410161493 District – Almora 4. Someshwar 1. Ms. Monika Mehra D/o Sh. Kishan Singh Mehra 9927226544 Village Mehragaon, PO-Rasyaragaon Tehsil-Someshwar, District Almora 2. Ms. Deepa Joshi D/o Sh. Prakash Chandra Joshi 8476052851 Village – Sarp, PO-Someshwar, District – Almora 3. Smt. Nirmala Tiwari W/o Sh. Bhuvan Chandra tiwari, R/o 9412924407 Village-Baigniya, Someshwar, Almora 5. Almora 1. Ms. Deepa Pandey, D/o Sh. Vinay Kumar, R/o Talla 9458371536 Kholta, Tehsil & Distt.-Almora 2. -

Uttarakhand Van Panchayats

Law Environment and Development JournalLEAD ADMINISTRATIVE AND POLICY BOTTLENECKS IN EFFECTIVE MANAGEMENT OF VAN PANCHAYATS IN UTTARAKHAND, INDIA B.S. Negi, D.S. Chauhan and N.P. Todaria COMMENT VOLUME 8/1 LEAD Journal (Law, Environment and Development Journal) is a peer-reviewed academic publication based in New Delhi and London and jointly managed by the School of Law, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) - University of London and the International Environmental Law Research Centre (IELRC). LEAD is published at www.lead-journal.org ISSN 1746-5893 The Managing Editor, LEAD Journal, c/o International Environmental Law Research Centre (IELRC), International Environment House II, 1F, 7 Chemin de Balexert, 1219 Châtelaine-Geneva, Switzerland, Tel/fax: + 41 (0)22 79 72 623, [email protected] COMMENT ADMINISTRATIVE AND POLICY BOTTLENECKS IN EFFECTIVE MANAGEMENT OF VAN PANCHAYATS IN UTTARAKHAND, INDIA B.S. Negi, D.S. Chauhan and N.P. Todaria This document can be cited as B.S. Negi, D.S. Chauhan and N.P. Todaria, ‘Administrative and Policy Bottlenecks in Effective Management of Van Panchayats in Uttarakhand, India’, 8/1 Law, Environment and Development Journal (2012), p. 141, available at http://www.lead-journal.org/content/12141.pdf B.S. Negi, Deputy Commissioner, Ministry of Agriculture, Govt. of India, Krishi Bhawan, New Delhi, India D.S. Chauhan, Department of Forestry, P.O. -59, HNB Garhwal University, Srinagar (Garhwal) – 246 174, Uttarakhand, India N.P. Todaria, Department of Forestry, P.O. -59, HNB Garhwal University, Srinagar (Garhwal) – 246 174, Uttarakhand, India, Email: [email protected] Published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 License TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

Third State Finance Commission

CHAPTER 5 STATUS OF DECENTRALISED GOVERNANCE A. Brief Historical Overview 5.1 Modern local government in India has a rather long history extending to the earliest years of British rule under the East India Company, when a municipal body was established in Madras in 1688 followed soon thereafter by Bombay and Calcutta. These earliest corporations neither had any legislative backing, having been set up on the instructions of the Directors of the East India Company with the consent of the Crown, nor were they representative bodies as they consisted entirely of nominated members from among the non-native population. They were set up mainly to provide sanitation in the Presidency towns, but they did not prove to be very effective in this task. Act X of 1842 was the first formal measure for the establishment of municipal bodies. Though applicable only to the Bengal Presidency it remained inoperative there. Town Committees under it were, however, set up in the two hill stations of Mussoorie and Nainital in 1842 and 1845 respectively, on the request of European residents. Uttarakhand thus has the distinction of having some of the earliest municipalities established in the country, outside the Presidency towns. Their record too was not very encouraging. When the Government of India passed Act XXVI in 1850 the municipal bodies of Mussoorie and Nainital were reconstituted under it. 5.2 The motivation for establishing municipal bodies in the initial years was not any commitment to local government on the part of the British. Rather it was inspired by the desire to raise money from the local population for provision of civic services. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Name : Prof. (Dr.) RAJESH BAHUGUNA Father’s Name : Late M. L. Bahuguna Date of Birth : 18th January, 1961 Contact Details : Address: Tapovan Enclave, Post-Tapovan, Dehradun, Uttarakhand- 248008. Telephone Nos. Residence- 135-2788638 Office - 135-2770305, 2770232 Mobile - 9412975564 E mail - vc@@uttaranchaluniversity.ac.in [email protected] [email protected] Aadhar - 920277107214 PAN - AHOPB6145Q Position held : Vice Chancellor (Officiating) Uttaranchal University Arcadia Grant, Post Chandanwari, Prem Nagar, Dehradun, Uttarakhand-248007 Academic Qualification: Ph.D. (Law) from Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra, Haryana on the subject- Alternative Dispute Resolution System in India. NET Qualified. University Grant Commission. LL.M. J.N.V. Jodhpur University, Jodhpur, Rajasthan. LL.B. J.N.V. Jodhpur University, Jodhpur, Rajasthan. B.Com. H.N.B. Garhwal University, Srinagar, Garhwal, Uttrakhand Trained Mediator: Successfully completed 40 hours Training of Mediators conducted by The International Centre for Alternative Dispute Resolution, New Delhi from 30th, 31st May & 1st June, 2015 and 19th & 20th June, 2015. Editor-in-Chief: Dehradun Law Review: A Journal of Law College Dehradun, Uttaranchal University Dehradun, Uttarakhand. ISSN: 2231-1157. (UGC listed Journal) For more details click on http://www.dehradunlawreview.com/ LCD Newsletter: A Newsletter of LCD, Uttaranchal University For more details click on https://uttaranchaluniversity.ac.in/colleges/law/newsletter/ Specializations: Constitutional Law. Alternative Dispute Resolution. Total Working Experience: 37 Years 1. Teaching/Research/Administrative Experience: 25.2 Years Vice Chancellor (Officiating) Uttaranchal University since 9th May, 2020 Dean, Law College Dehradun, faculty of Uttaranchal University, Dehradun since 24th June, 2013. Principal, Law College Dehradun, faculty of Uttaranchal University, Dehradun, 24th June, 2013 to 8th May 2020. -

Tariff Orders for FY 2018-19

Order on True up for FY 2016-17, Annual Performance Review for FY 2017-18 & ARR for FY 2018-19 For Power Transmission Corporation of Uttarakhand Ltd. March 21, 2018 Uttarakhand Electricity Regulatory Commission Vidyut Niyamak Bhawan, Near I.S.B.T., P.O. Majra Dehradun – 248171 Table of Contents 1 Background and Procedural History .................................................................................................... 4 2 Stakeholders’ Objections/Suggestions, Petitioner’s Responses and Commission’s Views ...... 8 2.1 Capitalisation of New Assets ...................................................................................................................... 8 2.1.1 Stakeholder’s Comments ........................................................................................................................... 8 2.1.2 Petitioner’s Response ................................................................................................................................. 8 2.1.3 Commission’s Views .................................................................................................................................. 9 2.2 Carrying Cost of Deficit ............................................................................................................................. 10 2.2.1 Stakeholder’s Comments ......................................................................................................................... 10 2.2.2 Petitioner’s Response .............................................................................................................................. -

From Dreams to Reality Compendium of Best Practices in Rural Sanitation in India

From Dreams to Reality Compendium of Best Practices in Rural Sanitation in India Water and Sanitation Program Ministry of Rural Development The World Bank Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation 55 Lodi Estate, 9th Floor, Paryavaran Bhawan New Delhi 110 003, India CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, Phone: (91-11) 24690488, 24690489 New Delhi 110 003, India Fax: (91-11) 24628250 Phone: (91-11) 24362705 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (91-11) 24361062 Web site: www.wsp.org E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.ddws.nic.in/ Designed by: Roots Advertising Services Pvt. Ltd. Printed at: Thomson Press October 2010/250 copies From Dreams to Reality Compendium of Best Practices in Rural Sanitation in India From Dreams to Reality Abbreviations ADC Assistant District Collector NIRD National Institute of Rural ASHA Accredited Social Health Activist Development BP block panchayat NL natural leader BPL below poverty line NREGS National Rural Employment BRGF Backward Regions Grant Fund Guarantee Scheme CGG Centre for Good Governance NRHM National Rural Health Mission CLASS community-led action for sanitary O&M operation and maintenance surveillance OD open defecation CLTS Community-Led Total Sanitation ODF Open defecation free CLTSC Community-Led Total Sanitation PI Panchayat Inspector Campaign PMU Project Management Unit CMAS contract management advisory service PRI Panchayati Raj Institutions CSC community sanitary complex PTA parent-teacher association DSC Divisional Sanitation Coordinator RDA Rural Development Assistant DSU District Support Unit RMDD -

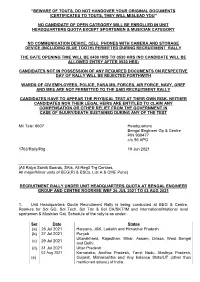

Beware of Touts, Do Not Handover Your Original Documents /Certificates to Touts, They Will Mislead You”

“BEWARE OF TOUTS, DO NOT HANDOVER YOUR ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS /CERTIFICATES TO TOUTS, THEY WILL MISLEAD YOU” NO CANDIDATE OF OPEN CATEGORY WILL BE ENROLLED IN UNIT HEADQUARTERS QUOTA EXCEPT SPORTSMEN & MUSICIAN CATEGORY NO COMMUNICATION DEVICE, CELL PHONES WITH CAMERA AND STORAGE DEVICE (INCLUDING BLUE TOOTH) PERMITTED DURING RECRUITMENT RALLY THE GATE OPENING TIME WILL BE 0430 HRS TO 0530 HRS (NO CANDIDATE WILL BE ALLOWED ENTRY AFTER 0530 HRS) CANDIDATES NOT IN POSSESSION OF ANY REQUIRED DOCUMENTS ON RESPECTIVE DAY OF RALLY WILL BE REJECTED FORTHWITH WARDS OF CIV EMPLOYEES, POLICE, PARA MIL FORCES, AIR FORCE, NAVY, GREF AND MES ARE NOT PERMITTED TO THE SAID RECRUITMENT RALLY CANDIDATES HAVE TO APPEAR THE PHYSICAL TEST AT THEIR OWN RISK. NEITHER CANDIDATES NOR THEIR LEGAL HEIRS ARE ENTITLED TO CLAIM ANY COMPENSATION OR OTHER RELIEF FROM THE GOVERNMENT IN CASE OF INJURY/DEATH SUSTAINED DURING ANY OF THE TEST Mil Tele: 6607 Headquarters Bengal Engineer Gp & Centre PIN 900477 c/o 56 APO 1763/Rally/Rtg 19 Jun 2021 _________________________________________ (All Rajya Sainik Boards, SAIs, All Regtl Trg Centres, All major/Minor units of BEG(R) & BSCs, List A & CME Pune) RECRUITMENT RALLY UNDER UNIT HEADQUARTERS QUOTA AT BENGAL ENGINEER GROUP AND CENTRE ROORKEE WEF 26 JUL 2021 TO 03 AUG 2021 1. Unit Headquarters Quota Recruitment Rally is being conducted at BEG & Centre, Roorkee for Sol GD, Sol Tech, Sol Tdn & Sol Clk/SKT/IM and International/National level sportsmen & Musician Cat. Schedule of the rally is as under:- Ser Date States (a) 26 Jul 2021 Haryana, J&K, Ladakh and Himachal Pradesh (b) 27 Jul 2021 Punjab Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Bihar, Assam, Orissa, West Bengal (c) 29 Jul 2021 and Delhi (d) 31 Jul 2021 Uttar Pradesh 02 Aug 2021 Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, (e) Gujarat, Maharashtra and Any balance State/UT (other than mentioned above) of India. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ______VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 ______

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 ________________________________________________________ LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI ___________________________________ The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 CONTENTS PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES PROCEDURAL MATTERS PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha Rajya Sabha State Legislatures RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Second Session of the Seventeenth Lok Sabha II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 250th Session of the Rajya Sabha III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and assented to by the President during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 V. List of Bills passed by the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 VI. Ordinances promulgated by the Union and State Governments during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 VII. Party Position in the Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha and the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITES ______________________________________________________________________________ CONFERENCES AND SYMPOSIA 141st Assembly of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU): The 141st Assembly of the IPU was held in Belgrade, Serbia from 13 to 17 October, 2019. An Indian Parliamentary Delegation led by Shri Om Birla, Hon’ble Speaker, Lok Sabha and consisting of Dr. Shashi Tharoor, Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha; Ms. Kanimozhi Karunanidhi, Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha; Smt. -

A Case Study of Women Leadership in Pris at Gram Panchayat

A Case Study on Women leadership in Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRI) at the Gram Panchayat level Name of Principal Investigator (PI): Narender Paul Name of Organization: CORD Thematic area of “Case”: Women’s Empowerment and Community Development Location of Gram Panchayat: Soukani Da Kot Panchayat in District Kangra of Himachal Pradesh Office of National Director CORD and CORD Training Centre, Sidhbari Tehsil Dharmshala, District Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, 176057 Phone Number: 91-1892-236987, Fax: 91-1892-235829 Email: [email protected], Web: www.cordindia.in 1 | P a g e I. Executive Summary: This case study focuses on the life and accomplishments of Smt. Mamta Devi, a young woman from the marginalised Schedule Caste (SC) community of Soukni-da-Kot Panchayat. Smt. Mamta Devi is currently serving her 2nd term as the President of her Panchayat. This Panchayat is located in the Dharamshala block of District Kangra in Himachal Pradesh. This case study explores how elected women leaders in the PRI succeed in their role despite the highly patriarchal and traditional social norms prevalent in the region. Interview schedules, Observations and Focused Group Discussions (FGDs) were used to elicit the required information including the demographic profile of the respondents, factors affecting EWR in performing their roles and in obtaining their expectation and suggestions for better leaderships. Smt. Mamta Devi’s story is an excellent story of women-empowerment, leadership in PRI and community development. Mamta Devi has significantly contributed in the development of her Panchayat. Both intrinsic and extrinsic factors led to the success of Mamta. These factors include developing herself first through awareness and trainings from odd jobs for her livelihood, good intension to do something for herself and others through network with agencies like CORD (NGO) and government before the leadership role of becoming an effective and capable Pradhan. -

The Uttar Pradesh Tax on Entry of Goods Into Local

The Uttarakhand Tax on Entry of Goods into Local Areas Act, 2008 Act 13 of 2008 Keyword(s): Business, Dealer, Entry of Goods, Tax, Value of Goods DISCLAIMER: This document is being furnished to you for your information by PRS Legislative Research (PRS). The contents of this document have been obtained from sources PRS believes to be reliable. These contents have not been independently verified, and PRS makes no representation or warranty as to the accuracy, completeness or correctness. In some cases the Principal Act and/or Amendment Act may not be available. Principal Acts may or may not include subsequent amendments. For authoritative text, please contact the relevant state department concerned or refer to the latest government publication or the gazette notification. Any person using this material should take their own professional and legal advice before acting on any information contained in this document. PRS or any persons connected with it do not accept any liability arising from the use of this document. PRS or any persons connected with it shall not be in any way responsible for any loss, damage, or distress to any person on account of any action taken or not taken on the basis of this document. THE UTTARAKHAND TAX ON ENTRY OF GOODS INTO LOCAL AREAS Act, 2008 In pursuance of the provision of clause(3) of Article 348 of the Constitution of India , the Governer is pleased to order the publication of the following English translation of “ The Uttarakhand Tax on Entry of Goods into local Areas Act, 2008”( Uttarakhand Adhiniyam Sankhaya 13 of 2008): As passed by the Uttarakhand Legislative Assembly and assesnted to by the Governer on 24 December, 2008 No.217/ XXXVI (3)/30/2008 Dated Dehradun, December 26,2008 NOTIFICATION Miscellaneous THE UTTARAKHAND TAX ON ENTRY OF GOODS INTO LOCAL AREAS Act, 2008 (Uttrakhand Act No. -

Local Self Governments High Court Judgement Uttarakhand.PDF

Gram Sabha Mawkot And Others vs State Of Uttarakhand And Others on 14 May, 2018 Uttaranchal High Court Gram Sabha Mawkot And Others vs State Of Uttarakhand And Others on 14 May, 2018 Judgment Reserved on : 08.05.2018 Delivered on : 14.05.2018 IN THE HIGH COURT OF UTTARAKHAND AT NAINITAL Writ Petition (M/S) No. 1047 of 2018 Gram Sabha Mawakot & others ..........Petitioners Versus State of Uttarakhand & others .......Respondents With Writ Petition (M/S) No. 1101 of 2018 Purushottam Puri and another ..........Petitioners Versus State of Uttarakhand & others .......Respondents With Writ Petition (M/S) No. 1107 of 2018 Smt. Guddi Devi & others ..........Petitioners Versus State of Uttarakhand & others .......Respondents With Writ Petition (M/S) No. 1276 of 2018 Gram Panchayat Daula & another ..........Petitioners Versus State of Uttarakhand & others .......Respondents 2 Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/154264990/ 1 Gram Sabha Mawkot And Others vs State Of Uttarakhand And Others on 14 May, 2018 With Writ Petition (M/S) No. 1286 of 2018 Hari Om Sethi ..............Petitioner Versus State of Uttarakhand & others .......Respondents With Writ Petition (M/S) No. 1292 of 2018 Govind Singh Bisht ..........Petitioner Versus State of Uttarakhand & others .......Respondents With Writ Petition (M/S) No. 1287 of 2018 Pitambar Dutt Tiwari & another ..........Petitioners Versus State of Uttarakhand & others .......Respondents With Writ Petition (M/S) No. 1266 of 2018 Ankit Panwar ..........Petitioner Versus State of Uttarakhand .......Respondent With Writ Petition (M/S) No. 1183 of 2018 Gram Panchayat Hempur Ismile & others ..........Petitioners Versus State of Uttarakhand & others .......Respondents 3 Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/154264990/ 2 Gram Sabha Mawkot And Others vs State Of Uttarakhand And Others on 14 May, 2018 With Writ Petition (M/S) No. -

40648-034: Infrastructure Development Investment Program

Resettlement Planning Document Project Number: 40648-034 November 2015 IND: Infrastructure Development Investment Program for Tourism (IDIPT) - Tranche 3 Sub Project : Due Diligence Report of Conservation of cultural heritage and urban place making in Nainital Submitted by Program Management Unit, (IDIPT-Tourism), Government of Uttarakhand, Dehrdaun This resettlement due diligence report has been prepared by the Program Management Unit, (IDIPT- Tourism), Government of Uttarakhand, Dehrdaun for the Asian Development Bank and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2011). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. This resettlement due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Involuntary Resettlement Due Diligence Report Nainital Lake Precinct Revitalization, Enhancement and Urban Place making Involuntary Resettlement Due Diligence Report Document Stage: Due Diligence Report Loan No: 3223 IND Package No: UK/IDIPT-III/BHT/02 November 2015 INDIA: Infrastructure Development Investment Programme for Tourism, Uttarakhand, SUB PROJECT: Nainital Lake Precinct Revitalization, Enhancement and Urban Place making Prepared by the Government of Uttarakhand for the Asian Development Bank This Resettlement Plan/Due Diligence Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature.