How Is Rush Canadian?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rush Three of Them Decided to - Geddy Recieved a Phone Reform Rush but Without Call from Alex

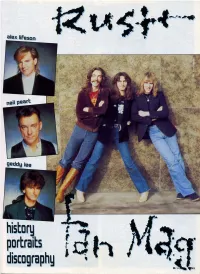

history portraits J , • • • discography •M!.. ..45 I geddylee J bliss,s nth.slzers. vDcals neil pearl: percussion • alex liFesDn guitars. synt.hesizers plcs: Relay Photos Ltd (8); Mark Weiss (2); Tom Farrington (1): Georg Chin (1) called Gary Lee, generally the rhythm 'n' blues known as 'Geddy' be combo Ogilvie, who cause of his Polish/Jewish shortly afterwards also roots, and a bassist rarely changed their me to seen playing anything JUdd, splitting up in Sep other than a Yardbirds bass tember of the sa'l1le year. line. John and Alex, w. 0 were In September of the same in Hadrian, contacted year The Projection had Geddy again, and the renamed themselves Rush three of them decided to - Geddy recieved a phone reform Rush but without call from Alex. who was in Lindy Young, who had deep trouble. Jeff Jones started his niversity was nowhere to be found, course by then. In Autumn although a gig was 1969 the first Led Zeppelin planned for that evening. LP was released, and it hit Because the band badly Alex, Geddy an(i John like needed the money, Geddy a hammer. Rush shut them helped them out, not just selves away in their rehe providing his amp, but also arsal rooms, tUfned up the jumping in at short notice amp and discovered the to play bass and sing. He fascination of heavy was familiar with the Rush metaL. set alreadY, as they only The following months played well-known cover were going toJprove tough versions, and with his high for the three fYoung musi voice reminiscent of Ro cians who were either still bert Plant, he comple at school or at work. -

Geddy Lee DI-2112 Signature

POWER REQUIREMENTS •Utilizes two (2) standard 9V alkaline batteries (not included). NOTE: Input jack activates batteries. To conserve energy, unplug when not in use. Power Consumption: approx. 55mA. Geddy Lee Signature •USE DC POWER SUPPLY ONLY! Failure to do so may damage the unit and void warranty. DC Power Supply Specifications: SansAmp DI-2112 -18V DC regulated or unregulated, 100mA minimum; -2.1mm female plug, center negative (-). •Refer to “Power Considerations” in Noteworthy Notes on page 8. WARNINGS: • Attempting to repair unit is not recommended and may void warranty. • Missing or altered serial numbers automatically void warranty. For your own protection: be sure serial number labels on the unit’s back plate and exterior box are intact, and return your warranty registration card. ONE YEAR LIMITED WARRANTY. PROOF OF PURCHASE REQUIRED. Manufacturer warrants unit to be free from defects in materials and workmanship for one (1) year from date of purchase to the original pur - chaser and is not transferable. This warranty does not include damage resulting from accident, misuse, abuse, alteration, or incorrect current or voltage. If unit becomes defective within warranty period, Tech 21 will repair or replace it free of charge. After expiration, Tech 21 will repair defective unit for a fee. ALL REPAIRS for residents of U.S. and Canada: Call Tech 21 for Return Authorization Number . Manufacturer will not accept packages without prior authorization, pre-paid freight (UPS preferred) and proper insurance. FOR PERSONAL ASSISTANCE & SERVICE: Contact Tech 21 weekdays from 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM, EST. Hand-built in the U.S.A. -

Orpe=Civ= V=Kfdeq Italic Flybynightitalic.Ttf

Examples Rush Font Name Rush File Name Album Element Notes Working Man WorkingMan.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song RUSH Working Man Titles Fly By Night, regular and FlyByNightregular.ttf. orpe=civ=_v=kfdeq italic FlyByNightitalic.ttf Caress Of Steel CaressOfSteel.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title Need to Photoshop to get the correct style RUSH CARESS OF STEEL Syrinx Syrinx.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song RUSH 2112 Titles ALL THE WORLD'S A STAGE (core font: Arial/Helvetica) Cover text Arial or Helvetica are core fonts for both Windows and Mac Farewell To Kings FarewellToKings.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song Rush A Farewell To Kings Titles Strangiato Strangiato.ttf Rush Logo Similar to illustrated "Rush" Rush Hemispheres Hemispheres.ttf Album Title Custom font by Dave Ward. Includes special character for "Rush". Hemispheres | RUSH THROUGH TIME RushThroughTime RushThroughTime.ttf Album Title RUSH Jacob's Ladder JacobsLadder.ttf Rush Logo Hybrid font PermanentWaves PermanentWaves.ttf Album Title permanent waves Moving Pictures MovingPictures.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title Same font used for Archives, Permanent Waves general text, RUSH MOVING PICTURES Moving Pictures and Different Stages Exit...Stage Left Bold ExitStageLeftBold.ttf Rush Logo RUSH Exit...Stage Left ExitStageLeft.ttf Album Title Exit...Stage Left SIGNALS (core font: Garamond) Album Title Garamond, a core font in Windows and Mac Grace Under Pressure GraceUnderPressure.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title, Upper Case character set only RUSH GRACE UNDER PRESSURE Song Titles RUSH Grand Designs GrandDesigns.ttf Rush Logo RUSH Grand Designs Lined GrandDesignsLined.ttf Alternate version Best used at 24pt or larger Power Windows PowerWindows.ttf Album Title, Song Titles POWER WINDOWS Hold Your Fire Black HoldYourFireBlack.ttf Rush Logo Need to Photoshop to get the correct style RUSH Hold Your Fire HoldYourFire.ttf Album Title, Song Titles HOLD YOUR FIRE A Show Of Hands AShowofHands.ttf Song Titles Same font as Power Windows. -

Toronto (Ontario, Canada) SELLER MANAGED Reseller Online Auction - Queen Street West

09/23/21 06:46:09 Toronto (Ontario, Canada) SELLER MANAGED Reseller Online Auction - Queen Street West Auction Opens: Sat, Jan 16 5:00pm ET Auction Closes: Wed, Jan 20 9:15pm ET Lot Title Lot Title 0075 Ramones - Road to Run A 0108 The Who x 2 A 0076 Traffic A 0109 Kraftwerk A 0077 The Flying Burrito Brothers A 0110 Paul Simon-Graceland A 0078 Herman's Hermits A 0111 Glass Harp A 0079 Death Wish II - Jimmy Page soundtrack A 0112 Rare Earth A 0080 The Wild Angels- soundtrack A 0113 Elton John -Tumbleweed A 0082 New Sealed!! Kevin Lamb A 0114 Vangelis A 0083 Django Reinhardt A 0115 Mandalaband A 0084 The B-52's A 0116 The Shirelles A 0085 Ella and Louis A 0117 Tenacious D - GREEN VINYL ! A 0086 Elvis Gold A 0118 Styx - GOLD VINYL ! A 0087 Johnny Cash Folsom Prison Blues. A 0119 Mahavishnu Orchestra A 0088 The Beatles VI A 0120 West, Bruce & Laing A 0089 Jeff Beck A 0121 David Lindley- El Rayo X A 0090 Steely Dan/ Katy Laid A 0122 BB King A 0091 Max Webster A 0123 Jazz albums lot A 0092 Tim Buckley A 0124 Indian record lot A 0093 AXE/ Randy Bachman A 0125 Genesis album lot A 0094 The Beatles Sgt Pepper A 0126 Supertramp records A 0095 Area Code 615 A 0127 Strawbs x 2 A 0096 Van Morrison - Best of A 0128 Soul Funk lot A 0097 David Bowie - Aladdin Sane A 0129 Schoolly D x 3 A 0098 Lightnin' Hopkins A 0130 Crosby, Stills, Nash x 3 A 0099 Jimmie Rodgers A 0131 Bananarama records festival A 0100 Karat A 0132 Indian music lot A 0101 Justin Hayward A 0133 New Wave lot A 0102 Martha and the Muffins A 0134 9 Indian music records A 0103 A Fistful of Dollars A 0135 Led Zeppelin x 3 A 0104 Yes- Relayer A 0136 9 rock records A 0105 Genesis Live A 0137 Adult Comedy albums A 0106 Randy Newman A 0138 9 rock records A 0107 Wings - At The Speed of Sound. -

Book > Deluxe Guitar TAB Collection Authentic

PK8C8FRUTC \ Deluxe Guitar TAB Collection Authentic Guitar TAB Authentic Guitar-Tab Editions / Book Deluxe Guitar TA B Collection A uth entic Guitar TA B A uth entic Guitar-Tab Editions By Staff Alfred Music. Paperback. Condition: New. 220 pages. Dimensions: 11.8in. x 8.9in. x 0.6in.This collection, covering 30 years in the career of the most successful and influential progressive rock band in history is a tribute to Rushs brilliant guitarist Alex Lifeson, one of the fathers of the progressive rock guitar genre. The book contains 22 prog-rock classics commencing in the mid-70s and concluding with chart success Snakes and Arrows, all in complete TAB. Titles: The Big Money Closer to the Heart Distant Early Warning Dreamline Far Cry Fly by Night Freewill Ghost of a Chance The Larger Bowl Limelight New World Man One Little Victory Red Barchetta Show Dont Tell The Spirit of Radio Subdivisions Test for Echo The Trees Tom Sawyer Vital Signs Working Man YYZ. This item ships from multiple locations. Your book may arrive from Roseburg,OR, La Vergne,TN. Perfect Paperback. READ ONLINE [ 1.16 MB ] Reviews Completely essential read through publication. It normally does not expense excessive. It is extremely diicult to leave it before concluding, once you begin to read the book. -- Morris Cruickshank Here is the best pdf i actually have go through till now. We have study and i also am certain that i am going to planning to go through once again once more in the future. You will not sense monotony at at any time of the time (that's what catalogs are for regarding in the event you question me). -

Rush Permanent Waves Mp3, Flac, Wma

Rush Permanent Waves mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Permanent Waves Country: US Released: 1980 Style: Hard Rock, Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1422 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1379 mb WMA version RAR size: 1257 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 899 Other Formats: APE DMF AU AUD FLAC MMF MP1 Tracklist Hide Credits 1 The Spirit Of Radio 4:56 2 Freewill 5:21 3 Jacob's Ladder 7:26 4 Entre Nous 4:36 Different Strings 5 3:48 Piano – Hugh Syme Natural Science (9:17) 6-I Tide Pools 6-II Hyperspace 6-III Permanent Waves Companies, etc. Marketed By – Mercury Records Manufactured By – Mercury Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – Mercury Records Copyright (c) – Mercury Records Copyright (c) – Anthem Entertainment Copyright (c) – Core Music Publishing Published By – Core Music Publishing Recorded At – Le Studio Mixed At – Trident Studios Mastered At – Gateway Mastering Pressed By – Sony DADC – 149845 2 Credits Arranged By – Rush Arranged By, Engineer – Terry Brown Art Direction, Graphics – Hugh Syme Artwork [Colour Collaboration] – Peter George Bass Guitar, Synthesizer [Oberheim Polyphonic, Ob-1, Mini Moog, Taurus Pedal], Vocals – Geddy Lee Cover [Concept] – Hugh Syme, Neil Peart Crew [Centre Stage Tehnician] – Larry (Shrav) Allen* Crew [Concert Rigging By] – Bill Collins Crew [Concert Sound Engineer] – Ian (The Weez) Grandy* Crew [Electrical Technician] – Ted (Theo) McDonald* Crew [Guitar And Synthesizer Maintenance] – Tony (Jack Secret) Geranios* Crew [Personal Shreve] – Sam (Shreve) Charters* Crew [Projectionist] – Harry (Tex) -

Getting to the Heart of Cultural Safety in Unama'ki

Getting to the Heart of Cultural Safety in Unama’ki: Considering kesultulinej (Love) De-Ann Sheppard Cape Breton University Cite as: Sheppard, D. M. (2020). Getting to the Heart of Cultural Safety in Unama’ki: Considering kesultulinej (Love). Witness: The Canadian Journal of Critical Nursing Discourse, Vol 2 (1), 51-65 https://doi.org/ 10.25071/2291-5796.57 Abstract Reflecting upon my early knowledge landscapes, situated within the unceded Mi’kmaq territory of Unama’ki (Cape Breton, Nova Scotia), living the Peace & Friendship Treaty and the teachings of Mi’kmaw Elders, I contemplate the essential relationship with land and language, specifically, kesultulinej (love as action) and etuaptmumk (two-eyed seeing) to Cultural Safety. I recognize my position, privilege, and Responsibility in teaching and learning about the contextual meanings of Cultural Safety, situated in specific Indigenous terrains and in relation with the land, across time, and relationships. Critical reflection on my story and experiences challenge me to consider why and how Maori nursing theorizations of Cultural Safety have been indoctrinated into the language of national nursing education by the Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (CASN), Canadian Nurses Association (CNA) and most provincial nursing regulatory bodies; this is increasingly relevant as nursing education is progressively shaped by neoliberal and Indigenizing agendas. As I contemplate wrapping Cultural Safety with kesultulinej, I see the potential to decolonize nursing. Mi’kmaw teachings of etuaptmumk and kesultulinej call forth Responsibilities to act, and in doing so move us into a space of potential to resist the colonizing forces within nursing. In this moment I realize the interconnected meaning of being amidst these relationships that matter to me as a person and as a nurse; relationships that are marked by love, care and compassion. -

The Social Meaning of Eh in Canadian English∗

THE SOCIAL MEANING OF EH IN CANADIAN ENGLISH∗ Derek Denis University of Toronto 1. Introduction. The recent surge in sociolinguistic investigation of pragmatic markers such as general extenders (and stuff, and things like that), discourse and quotative like, and utterance final tags (right, you know) has been primarily fuelled by questions about grammaticalization and language change (D’Arcy 2005; Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2007; Cheshire 2007; Tagliamonte and Denis 2010; Pichler and Levey 2011; Denis and Tagliamonte pear). Included in that set of pragmatic markers is eh, a very special variant (at least for Canadians). In this paper, I build on earlier work (Avis 1972; Johnson 1976; Gibson 1977; Gold 2005, 2008) and discuss the development of this very Canadian feature in terms of indexical order and indexi- cal change, along the lines of Silverstein’s seminal 2003 paper and Johnstone and Kiesling’s (Johnstone and Kiesling 2008; Johnstone 2009) work on Pittsburghese, which applies Silverstein’s framework. Although eh is well-known as the quintessential Canadian English stereo- type, there has been little research that discusses how exactly it came to hold this status. By tracking the points in time at which eh gained meanings at subse- quent orders of indexicality, a` la Silverstein (1993, 2003) and Johnstone (2009), I establish a timeline of the development of eh’s social meaning in Canada. My arguments draw on evidence based on the metadiscourse surrounding eh, perfor- mances of Canadian identity, real- and apparent-time data that tracks the usage of eh in Southern Ontario English over the last 130 years (Tagliamonte 2006; Denis 2012) and the commodification of eh. -

Trans-FM-Ottawa-CKCU.Pdf

A Gutetc CKCU 93.1 FN/ SOUVE\ IR EDITV ACT CKCU Celebrates 5 Years of Frequency Modulation Vrk.. \hi- PLUS: An interview with KimVitcholl Dcvid 30wie_ Fincerorintz-Levon He m-Fictionoy Ken Ric5;77), -Solit Enz-Conacicn Film FesfivcIs- onc more... ATTENTION STUDENTS! MILLION DOLLAR GOLD BUY CASH-CASH-CASH YES DIAMONDS WE BUY STERLING SILVER GOLD You Can Get Gold Jewellery -10K -14K -18K -22K E Jewellery Dental Gold Bangles Gold Coins Scrap Gold Bracelets Gold Wafers Chains Charms Placer Gold PHOTOCOPIES Rings Pocket Watches Platinum `Pendants Wrist Watches Silver Coins I 24 Hours A Day CASH FOR GOLD `r,u mu/ ,ap o,Kok Cal we pay cask r ;won, 000 5rr,rre r.n9. 5,2 no to 5,35 00 weareep ook ST 00 to SOO 00 Ir+Ore for Monday to Saturday darnOnC161 pocket *atones 565 00 to $250 00 y,u nol Sure v... vdr test rt t,re anti Make you an one, You .01 Irks CASH FOR STERLING CASH FOR DIAMONDS forks 11.91 SIZE GOOD EIETIERBEST Sorloott 33 Gloat530 $105 5200 Enron 4 84 CaratS70 $220 1450 Sofro. 50.00 s op I. Corot$125 $400 MOO Too Soto 25000 up Carol$200 $550 $1400 10% 2 CaratSSW $1200 S2850 Our Ottawa West Buying Office is now open Monday through Saturday Discount With This Ad 10:00 a.m.-7:00 p.m. penunays oontil 4PM MOW IT N... ITwow PARKING FACILITIES AVAILABLE 1I0041 VOLUAIKE CAMPBELL ELECTRONIC fist p 0,,r °ratedo ver rroorr YOU 'IOW Halklort Howe PRINTING SYSTEMS MI poops sublet -I to osorkot oottellitorto 6 orloo 2249 Carling A.m.., Soho 224 171 Slater Street, Ottawa INTERNATIONAL WE RESERVE THE RIGHT TO REFUtE ANY PURCHASE GOLD&DIAMOND INC. -

GEDDY EASTON 'LEE Master of the ,Hook Bass + Power = Progressive Pop ERIC 'JOHNSON the Wat M Tone of a TEXAS TWISTER

- 802135 MAY 1986 $2.50 Inside This Issue: A SPECIAL Billy Idol's STEVE STEVENS (not -so-secret) CASSETTE Secret See Page 54 Weapon For Details THE CARS' RUSH'S ELLIOT GEDDY EASTON 'LEE Master Of The ,Hook Bass + Power = Progressive Pop ERIC 'JOHNSON The Wat m Tone Of A TEXAS TWISTER PLUS: Lonnie Mack Albert Collins Roy Buchanan , 'Tony MacAlpine o Curtis Mayfield MORE BASS, MORE SPACE IN THE MODERN WORLD Power Windows is the best Rush albutn in years because the band ----and the bass---- has returned to the roots of its sound ... tneticulously. BY JOHN SWENSON It has been a long, vertiginous and damn exciting roller coaster ride for Rush over the past decade-and-a-half. The group has gone from being unabashed Led Zeppelinites to kings of the concept album to the thinking man's heavy metal band to an uneasy combination of eighties record ing styles and seventies relentlessness. One thing Rush has never done is rest on its collective laurels-bassist Geddy Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson and drummer Neil Peart have always been the first to point out the band's shortcomings when they feel legitimate deficiencies have surfaced. Accordingly, Lee was quick to admit his dissatisfaction with the band's last album, Grace Under Pressure , even though the record , which went platinum, has con solidated the band's position as one of Mercury/Polygram's most important acts. "We realized with Grace Under Pres sure ," said Lee on completion of the new album , Power Windows, "that we were not a techno-pop band. -

Diciembre 2014 CULTURA BLUES. LA REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA Página | 1

Número 43 – Diciembre 2014 CULTURA BLUES. LA REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA Página | 1 Índice Directorio PORTADA Mississippi Heat: Warning Shot (1) ……………….….…….… 1 Cultura Blues. La revista electrónica Fotos: Cortesía Pierre Lacocque: Press Kit Mississippi Heat “Un concepto distinto del blues y algo más…” ÍNDICE-DIRECTORIO ……..……………………………………………..…..… 2 www.culturablues.com EDITORIAL Fin de año ¿Felices fiestas? (2) …………………………..…. 3 Año 3 Núm. 43 – diciembre de 2014 Derechos Reservados 04 – 2013 – 042911362800 – 203 BLUES A LA CARTA Registro ante INDAUTOR Pierre Lacocque - Mississippi Heat - Warning Shot (2) ………………….... 5 POR SEGURIDAD DE LOS USUARIOS Director general y editor: Al vacío (3) ……………………….……………………….…………………………………. 10 José Luis García Fernández CORTANDO RÁBANOS De tradición y nuevas rolas (4) ……… 15 Subdirector general: José Alfredo Reyes Palacios HUELLA AZUL Entrevista a los Hot Tamales (5, 6 y 7) …………… 17 SESIONES DESDE LA CABINA Programación y diseño: Blue rondo a la Brubeck (8) ………………………………………..………….……. 21 José Luis García Vázquez Aida Castillo Arroyo CULTURA BLUES de visita en… Biblioteca Benjamín Franklin Consejo Editorial: Casa de Cultura Iztaccíhuatl Mario Martínez Valdez Blues Club Ruta 61 María Luisa Méndez Flores Casa de Cultura de Azcapotzalco (2) ……………………………...………….. 23 Colaboradores en este número: DE COLECCIÓN El retorno de Cat Stevens/Yusuf Islam. Segunda parte 1. José Luis García Vázquez 120 discos de blues publicados en 2014 (2) ………………………..…..…... 28 2. José Luis García Fernández 3. José Alfredo Reyes Palacios COLABORACIÓN ESPECIAL 1 ¿Blues en español? (10) ..... 38 4. Frino 5. María Luisa Méndez Flores COLABORACIÓN ESPECIAL 2 In Memoriam (2 y 7) …........ 40 6. Fernando Monroy Estrada 7. Félix Fernando Franco Frías -Q.E.P.D.- UNA EXPERIENCIA 8. Yonathan Amador Gómez Jambalaya. -

ATTENTION All Planets of the Solar Federationii'

i~~30 . .~,.~.* ~~~ Welcome to the latest issue of 'Spirit'. From this issue we are reverting to quarterly publication, hopefully next year we will go back to bi-monthly, once the band are active again. Please join me in welcoming Stewart Gilray aboard as assistant editor. Good luck to Neil Elliott with the Dream Theater fan zine he is currently producing, Neil's address can be found in the perman ant trades section if you are interested. Alex will be appearing at this years Kumbaya Festival in Toronto on the 2nd September, as .... with previous years this Aids benefit show will feature the cream of Canadian talent, Vol 8 No 1 giving their all for a good cause. Ray our North American corespondent will be attending Published quarterly by:- the show (lucky bastard) he will be fileing a full report (with pictures) for the next issue, won't you Ray? Mick Burnett, Alex should have his solo album (see interview 23, Garden Close, beginning page 3) in the shops by October. Chinbrook Road, If all goes well the album should be released Grove Park, in Europe at the same time as North America. London. Next issue of 'Spirit' should have an exclus S-E-12 9-T-G ive interview with Alex telling us all about England. the album. Editor: Mick Burnett The band should be getting back together to Asst Editor: Stewart Gilray begin work writing the new album in September. Typist: Janet Balmer Recording to commence Jan/Feb of next year Printers: C.J.L. with Peter Collins once more at the helm.