Ernest C. Oberholtzer (1884- 1977)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NUNAVUT a 100 , 101 H Ackett R Iver , Wishbone Xstrata Zinc Canada R Ye C Lve Coal T Rto Nickel-Copper-PGE 102, 103 H Igh Lake , Izo K Lake M M G Resources Inc

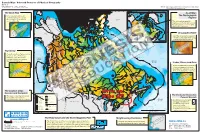

150°W 140°W 130°W 120°W 110°W 100°W 90°W 80°W 70°W 60°W 50°W 40°W 30°W PROJECTS BY REGION Note: Bold project number and name signifies major or advancing project. AR CT KITIKMEOT REGION 8 I 0 C LEGEND ° O N umber P ro ject Operato r N O C C E Commodity Groupings ÉA AN B A SE M ET A LS Mineral Exploration, Mining and Geoscience N Base Metals Iron NUNAVUT A 100 , 101 H ackett R iver , Wishbone Xstrata Zinc Canada R Ye C lve Coal T rto Nickel-Copper-PGE 102, 103 H igh Lake , Izo k Lake M M G Resources Inc. I n B P Q ay q N Diamond Active Projects 2012 U paa Rare Earth Elements 104 Hood M M G Resources Inc. E inir utt Gold Uranium 0 50 100 200 300 S Q D IA M ON D S t D i a Active Mine Inactive Mine 160 Hammer Stornoway Diamond Corporation N H r Kilometres T t A S L E 161 Jericho M ine Shear Diamonds Ltd. S B s Bold project number and name signifies major I e Projection: Canada Lambert Conformal Conic, NAD 83 A r D or advancing project. GOLD IS a N H L ay N A 220, 221 B ack R iver (Geo rge Lake - 220, Go o se Lake - 221) Sabina Gold & Silver Corp. T dhild B É Au N L Areas with Surface and/or Subsurface Restrictions E - a PRODUCED BY: B n N ) Committee Bay (Anuri-Raven - 222, Four Hills-Cop - 223, Inuk - E s E E A e ER t K CPMA Caribou Protection Measures Apply 222 - 226 North Country Gold Corp. -

198 13. Repulse Bay. This Is an Important Summer Area for Seals

198 13. Repulse Bay. This is an important summer area for seals (Canadian Wildlife Service 1972) and a primary seal-hunting area for Repulse Bay. 14. Roes Welcome Sound. This is an important concentration area for ringed seals and an important hunting area for Repulse Bay. Marine traffic, materials staging, and construction of the crossing could displace seals or degrade their habitat. 15. Southampton-Coats Island. The southern coastal area of Southampton Island is an important concentration area for ringed seals and is the primary ringed and bearded seal hunting area for the Coral Harbour Inuit. Fisher and Evans Straits and all coasts of Coats Island are important seal-hunting areas in late summer and early fall. Marine traffic, materials staging, and construction of the crossing could displace seals or degrade their habitat. 16.7.2 Communities Affected Communities that could be affected by impacts on seal populations are Resolute and, to a lesser degree, Spence Bay, Chesterfield Inlet, and Gjoa Haven. Effects on Arctic Bay would be minor. Coral Harbour and Repulse Bay could be affected if the Quebec route were chosen. Seal meat makes up the most important part of the diet in Resolute, Spence Bay, Coral Harbour, Repulse Bay, and Arctic Bay. It is a secondary, but still important food in Chesterfield Inlet and Gjoa Haven. Seal skins are an important source of income for Spence Bay, Resolute, Coral Harbour, Repulse Bay, and Arctic Bay and a less important income source for Chesterfield Inlet and Gjoa Haven. 16.7.3 Data Gaps Major data gaps concerning impacts on seal populations are: 1. -

Canadian Data Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2262

Scientific Excellence • Resource Protection & Conservation • Benefits for Canadians Excellence scientifique • Protection et conservation des ressources • Bénéfices aux Canadiens DFO Lib ary MPO B bhotheque Ill 11 11 11 12022686 11 A Review of the Status and Harvests of Fish, Invertebrate, and Marine Mammal Stocks in the Nunavut Settlement Area D.B. Stewart Central and Arctic Region Department of Fisheries and Oceans Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N6 1994 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2262 . 51( P_ .3 AS-5 -- I__2,7 Fisheries Pêches 1+1 1+1and Oceans et Océans CanaclUi ILIIM Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Manuscript reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which deals with national or regional problems. Distribu- tion is restricted to institutions or individuals located in particular regions of Canada. However, no restriction is placed on subject matter, and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Manuscript reports may be cited as full-publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts and,indexed in the Department's annual index to scientific and technical publications. Numbers 1-900 in this series were issued as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Biological Board of Canada, and subsequent to 1937 when the name of the Board was changed by Act of Parliament, as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 901-1425 were issued as Manuscript Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. -

Following the Oberholtzer-Magee Expedition, by David F. Pelly

246 • REVIEWS Yoo, J.C., and D’Odorico, P. 2002. Trends and fluctuations in the likely caribou crossings and waited, the Dene [Chipewyan] dates of ice break-up of lakes and rivers in northern Europe: The were more inclined to simply follow the caribou in their effect of the North Atlantic Oscillation. Journal of Hydrology migration, not unlike a pack of wolves” (p. 64). The hostil- 268:100–112. ity between them made it difficult for anyone to find a guide Zhang, X., Vincent, L.A., Hogg, W.D., and Niitsoo, A. 2000. to conduct him through the territory. Temperature and precipitation trends in Canada during the Pelly does a kind of time-travel through the history of the 20th century. Atmosphere-Ocean 38:395–429. area, going back to the time of Samuel Hearne in the 18th century and up to the descriptions of Bill Layman, who is Thomas Huntington still canoeing the area today. The narrative ranges from the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences mid-19th century, when the Roman Catholic mission was 180 McKown Point Rd. established in the village of Brochet at the head of Reindeer West Boothbay Harbor, Maine 04575, USA Lake, to the travels of American P.G. Downes, who in 1939 [email protected] covered some of the same route traveled by Oberholtzer and Magee 27 years earlier. Pelly traces centuries of nomadic movement of the Chipewyan, the Inuit, and the Cree as they The Old Way North: following the Ober- followed the caribou across the land, sometimes in co-op- holtzer-Magee expedition. -

NTI IIBA for Conservation Areas Cultural Heritage and Interpretative

NTI IIBA for Phase I: Cultural Heritage Resources Conservation Areas Report Cultural Heritage Area: McConnell River and Interpretative Migratory Bird Sanctuary Materials Study Prepared for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 1 May 2011 This Cultural Heritage Report: McConnell River Migratory Bird Sanctuary (Arviat) is part of a set of studies and a database produced for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. as part of the project: NTI IIBA for Conservation Areas, Cultural Resources Inventory and Interpretative Materials Study Inquiries concerning this project and the report should be addressed to: David Kunuk Director of Implementation Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 3rd Floor, Igluvut Bldg. P.O. Box 638 Iqaluit, Nunavut X0A 0H0 E: [email protected] T: (867) 975‐4900 Project Manager, Consulting Team: Julie Harris Contentworks Inc. 137 Second Avenue, Suite 1 Ottawa, ON K1S 2H4 Tel: (613) 730‐4059 Email: [email protected] Cultural Heritage Report: McConnell River Migratory Bird Sanctuary (Arviat) Authors: Philip Goldring, Consultant: Historian and Heritage/Place Names Specialist (primary author) Julie Harris, Contentworks Inc.: Heritage Specialist and Historian Nicole Brandon, Consultant: Archaeologist Luke Suluk, Consultant: Inuit Cultural Specialist/Archaeologist Frances Okatsiak, Consultant: Collections Researcher Note on Place Names: The current official names of places are used here except in direct quotations from historical documents. Throughout the document Arviat refers to the settlement established in the 1950s and previously known as Eskimo Point. Names of -

River Ice Breakup, Edited by Spyros Beltaos

244 • REVIEWS A final criticism concerns the incompleteness of the bib- a substantial body of knowledge that had been published liography. At many places, McGoogan quotes from books in a wide assortment of conference proceedings, technical by members of Kane’s second expedition, including Robert reports, scientific journal articles, and books and to identify Goodfellow, Hans Hendrick, Christopher Hicky, and Amos key gaps in current knowledge. Bonsall, but not one of these works appears in the bibliog- The book attempts to bridge the gap between earlier, raphy. Admittedly this is termed a “Select Bibliography,” largely empirical, approaches to studying river ice breakup but it certainly ought to contain all the works from which and more recent theoretical approaches, with emphasis on McGoogan has quoted. prediction. The theoretical approach uses quantitative appli- In short, while the uncritical reader may perhaps find cation of the thermodynamics of heat transfer, hydrology, this “a good read,” the discerning reader will soon detect hydraulics, and ice mechanics. Beltaos acknowledges both that this biography has been rather carelessly researched. the complexity of predicting these processes and the typical lack of detailed information on channel geometry, bathym- etry, stream bed slope and tortuosity, hydraulics, and REFERENCES hydrology, which require a balance between using quan- titative approaches and applying qualitative or empirical Blake, E.V., ed. 1874. Arctic experiences: Containing Capt. relations. Engineers and water resource managers will find George E. Tyson’s wonderful drift on the ice-floe, a history of many examples of how to apply quantitative approaches the Polaris expedition, the cruise of the Tigress and rescue of using approximations or empirical relations to estimate req- the Polaris survivors. -

Nunavut-Manitoba Route Selection Study: Final Report

NISHI-KHON/SNCLAVALIN November 14, 2007 BY EMAIL Kivalliq Inuit Association P.O. Box 340 Rankin Inlet, NU X0C 0G0 016259-30RA Attention: Melodie Sammurtok, Project Manager Dear Ms. Sammurtok: Re: Nunavut-Manitoba Route Selection Study: Final Report We are pleased to submit the final documentation of the Nunavut-Manitoba Route Selection Study as a concluding deliverable of this two-year multi-disciplinary study. An electronic copy of the Final Report is submitted initially via email. One hard-copy report will be subsequently provided to each member of the Project Working Group, along with a CD containing the electronic copies of the Final and Milestone Reports, along with all the associated Appendices. On behalf of the Nishi-Khon/SNC-Lavlin Consultant Team, we would like to thank you, members of the Project Working Group and the Project Steering Committee, for your guidance and valuable contributions to this study. It has been our pleasure to work with KIA, Nunavut, Manitoba and Transport Canada on this challenging project. We look forward to continuing working with you over the next few years on the business case development, more detailed engineering and environmental studies necessary to bring this important project to fruition. Yours truly, SNCLAVALIN INC. Tim Stevens, P. Eng. Project Manager Enclosures DISTRIBUTION LIST Project Steering Committee: Methusalah Kunuk Assistant Deputy Minister, Transportation, Nunavut Department of Economic Development & Transportation Tongola Sandy President, Kivalliq Inuit Association John Spacek Assistant -

Taiga Shield Ecozone Kazan River Upland Ecoregion Taiga Shield Ecozone the Taiga Shield Ecozone Lies on Either Side of Hudson Bay

Terrestrial Ecozones, Ecoregions, and Ecodistricts of Manitoba An Ecological Stratification of Manitoba’s Natural Landscapes Research Branch Technical Bulletin 1998-9E R.E. Smith, H. Veldhuis, G.F. Mills, R.G. Eilers, W.R. Fraser, and G.W. Lelyk Land Resource Unit Brandon Research Centre, Research Branch Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Taiga Shield Ecozone Kazan River Upland Ecoregion Taiga Shield Ecozone The Taiga Shield Ecozone lies on either side of Hudson Bay. The eastern segment occupies the central part of Quebec and Labrador, and the western seg- ment occupies portions of north- ern Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and the south-eastern area of the continental North- west Territories, and the south- ern part of Nunavut. Character- istic of the zone are the open and often stunted conifer dominated forests, and the Precambrian shield with its shallow soils and many lakes. Climate The ecoclimate of the ecozone is classified as Subarctic, is a common occurrence in summer, especially in areas which is characterized by relatively short summers with with the stronger continental climate conditions. prolonged daylight, and long, very cold winters. Mean annual temperature in the area west of Hudson Bay is as Mean annual precipitation ranges from 200 to 500 mm low as -9.0oC, but it ranges from -1oC to -5oC in Quebec west of Hudson Bay, while east of Hudson Bay it ranges and Labrador, with some areas in Labrador having mean from 500 to 800 mm, to over 1000 mm locally along the annual temperatures as high as 1oC. A few degrees of frost Labrador coast. Selected Climate Data1 (Annual Means) for the Taiga Shield Ecozone Temperature Precipitation Degree Days Frost Free Period Station (oC) (>5oC) (days) Rain(mm) Snow(cm) Total(mm) Brochet A -4.9 261.8 167.5 427.1 952.0 97.0 Ennadai Lake -9.3 173.7 117.1 266.7 595.0 78.0 Uranium City A -3.5 204.9 197.9 344.8 1111.0 106.0 Yellowknife A -5.4 150.2 135.4 266.7 1027.0 111.0 1 Canadian Climate Normals, 1951-1980. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 – SEAL WATERSHED .............................................................................................................................................. 4 2 - THLEWIAZA WATERSHED ................................................................................................................................. 5 3 - GEILLINI WATERSHED ....................................................................................................................................... 7 4 - THA-ANNE WATERSHED .................................................................................................................................... 8 5 - THELON WATERSHED ........................................................................................................................................ 9 6 - DUBAWNT WATERSHED .................................................................................................................................. 11 7 - KAZAN WATERSHED ........................................................................................................................................ 13 8 - BAKER LAKE WATERSHED ............................................................................................................................. 15 9 - QUOICH WATERSHED ....................................................................................................................................... 17 10 - CHESTERFIELD INLET WATERSHED .......................................................................................................... -

Teacher's Guide

Canada Map / Selected Features of Physical Geography Map No. 50 ISBN: 978-2-89157-171-5 PRODUCT NO.: 401 1276 Washable: We strongly recommend the use of Crayola water-soluble markers. Bands and hooks 122 cm × 94 cm / 48 in × 37 in Other markers may damage your maps. 170° 160° 150° 140° 130° 120° 110° 100° 90° 80° 70° 60° 50° 40° 30° 20° 10° 170° 160° 150° 140° 130° 120° 110° 100° 90° 80° 70° 60° 50° 40° 30° 20° 10° RUSSIAN TCHOUKOTKA FEDERATION The Base Map [RUSSIAN FEDERATION] Inset Map: CANADA AND ITS LANDFORMS Canada Today ICELAND • Contours and outlines are The Physiographic Bering Strait Lake Hazen Arctic Ocean carefully stylized to capture DENMARK UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Regions Ellesmere Island 60° North Magnetic Pole Map No. 50 November 2003 GREENLAND 60° the essentials. Easy to read CANADA (Kalaallit Nunaat) [DENMARK] and user-friendly. selected features of physical geography • The seven physiographic Meighen Island Nares Strait regions are clearly represented Borden Island Amund Axel Ringnes Heiberg Ellef Island by seven bands of colour with Ringnes Island Pacific Atlantic Island Ocean Ocean Mackenzie King Island Prince Patrick Island well-dened contours. Arctic Ocean Lougheed Island Cornwall Island A rc Labrador Sea tic P Queen Elizabeth a O c ce Arctic Circle if a 50° ic n D Islands O ra Eglinton Island Graham Island 50° ce in Y an ag Cameron Island uk D e Hudson Bay on ra B in as a in ge B R as iv in Melville e r Island Coburg Island Bathurst 60° Island 60° Byam Martin Island Baffin Bay K ALASKA Cornwallis Devon Island Geographic Relief [UNITED STATES OF AMERICA] Beaufort Sea Island Po rc Banks Island up E in Sachs e Harbour Parry Channel R iver Legend Stefansson Island Parry Channel Cordilleran Region ukon Interior Plains Y • Identies all essential elements. -

A Second Expedition Through the Barren Lands of Northern Canada Author(S): J

A Second Expedition through the Barren Lands of Northern Canada Author(s): J. Burr Tyrrell Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 6, No. 5 (Nov., 1895), pp. 438-448 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1773980 Accessed: 25-06-2016 02:34 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley, The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 132.236.27.111 on Sat, 25 Jun 2016 02:34:40 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 438 A SECOND EXPEDITION THPtOUGH THE official language now is Spanish, but it is for that very reason I think the history so extremely interestin. I have been endeavourinffl to draw attention to the neeessity of its study, as soon we shall be losing all those threads which will enable us to make the study of the Wlesican past eSeetual. I am sure the studJr of the lanCuaCes would do a Creat deal to elueidate the very question just asked. If tile eazisting independent tribes in Mexieo eould be studied separately, and somethinC ascertained about their separate languages, their separate etlstoms, and identifiea- tion established between them and those to the north or the south, I thinli tllere is a great field for inquiry whieh would have extremelJr remarkable results. -

Nunavut Mineral Exploration, Mining and Geoscience Overview 2014

OVERVIEW 2014 NUNAVUT MINERAL EXPLORATION, MINING AND GEOSCIENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS Land Tenure in Nunavut ......................................................3 NOTE TO READERS Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada ..........4 This document has been prepared on the basis of information available at the time of writing. All resource and Government of Nunavut ......................................................7 reserve figures quoted in this publication are derived from Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated ...................................... 12 company news releases, websites, and technical reports Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office ................................. 14 filed with SEDAR (www.sedar.com). Readers are directed Summary of 2014 Exploration Activities to individual company websites for details on the reporting Kitikmeot Region ......................................................... 18 standards used. The authors make no warranty of any kind Base Metals ........................................................... 20 with respect to the content and accept no liability, either Gold ....................................................................... 22 incidental, consequential, financial or otherwise, arising Inactive Projects ..................................................... 29 from the use of this document. Kivalliq Region ............................................................ 30 Base Metals ........................................................... 32 All exploration information was gathered prior to