Lone Bellow – Episode Transcript Matt: for Those Who Are Unaware of Steven Pressfield, Pressfield Is an Author of a Book Called the War of Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

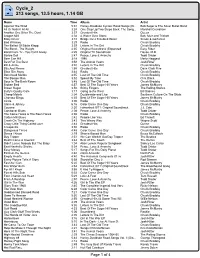

Cycle2 Playlist

Cycle_2 213 songs, 13.5 hours, 1.14 GB Name Time Album Artist Against The Wind 5:31 Harley-Davidson Cycles: Road Songs (Di... Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band All Or Nothin' At All 3:24 One Step Up/Two Steps Back: The Song... Marshall Crenshaw Another One Bites The Dust 3:37 Greatest Hits Queen Aragon Mill 4:02 A Water Over Stone Bok, Muir and Trickett Baby Driver 3:18 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel Bad Whiskey 3:29 Radio Chuck Brodsky The Ballad Of Eddie Klepp 3:39 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky The Band - The Weight 4:35 Original Soundtrack (Expanded Easy Rider Band From Tv - You Can't Alway 4:25 Original TV Soundtrack House, M.D. Barbie Doll 2:47 Peace, Love & Anarchy Todd Snider Beer Can Hill 3:18 1996 Merle Haggard Best For The Best 3:58 The Animal Years Josh Ritter Bill & Annie 3:40 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky Bits And Pieces 1:58 Greatest Hits Dave Clark Five Blow 'Em Away 3:44 Radio Chuck Brodsky Bonehead Merkle 4:35 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky The Boogie Man 3:52 Spend My Time Clint Black Boys In The Back Room 3:48 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky Broken Bed 4:57 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Brown Sugar 3:50 Sticky Fingers The Rolling Stones Buffy's Quality Cafe 3:17 Going to the West Bill Staines Cheap Motels 2:04 Doublewide and Live Southern Culture On The Skids Choctaw Bingo 8:35 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Circle 3:00 Radio Chuck Brodsky Claire & Johnny 6:16 Color Came One Day Chuck Brodsky Cocaine 2:50 Fahrenheit 9/11: Original Soundtrack J.J. -

The Tower, 26(7)

ii versityCr Volume XXV1 Issue Text Messaging Keeps Arcadia Safe By NEIL HUNIUNS and Terry Ryan the Assistant to Associate Editor Arcadias President Jerry Greiner On brisk afternoon in Though the system is an Glenside truck delivering liq exciting and critical addition to uid chlorine to nearby swim Arcadias safety measures ming pool is traveling north Bonner was careful to put its bound on Route 309 As it pass importance in perspective es Arcadias campus the tn E2C is just an added tool encounters debris on the road an Bonner stated emphasizing that the driver swerves the truck to Public Safety still maintains mul avoid the obstacles bit too tiple approaches to maximize hard of swerve it would seem as safety on campus This is just the truck topples over spilling the one of the tools we use to notify deadly liquid on to the highway students and faculty on campus breeze to allowing northerly this notification tion of the Emergency Bonner attended last winter Still new the toxic chlorine fumes sweep is addition for Notification System As the sce Six months later the lives of system powerful toward Arcadias campus Arcadia The is located nario above indicates this system 27 students and faculty mem system Moments later cell phones off and is on monopolizes on text messaging bers at Virginia Tech were taken campus separate across Arcadias buzz campus network from Arcadias Internet to alert students and faculty of by lone shooter in matter of Get inside and simultaneously service In the confu immediate threats to life per hours and the necessity -

Forum on North Korea Missis Crisis At

VOL. 103 ISSUE 9_ FOGHORN.USFCA.EDU NOVEMBER 16t2006 Contraversial Able Forum on North Korea Missis Crisis At USF Contract Deliberated SETAREH BANISDR McDonald a "liar" after he had stated that been unionized for a long enough period StaffWriter Able had presented a final contract offer 2 of time to negotiate for higher wages. She 1/2 weeks ago, and had not yet heard back mentioned that some of these unions have n Tuesday, Nov. 7, members of from the union. McDonald said in an e- not been established as long as SEIU has. the USF community and ASUSF mail the morning after Tuesday's meeting, Although the minimum wage in Osenate had the opportunity to "I checked with Able immediately before San Francisco is currendy $8.82, Mi hear both sides ofthe recent contract con the meeting, and again this morning, and randa said that anyone hving in the city' troversy with Able Building Maintenance the company has assured me that it has knows how expensive it is. She says Co., whose position the University sup not been contacted by the union is any that the janitors are forced to struggle, ports, and janitors at USF, represented by way." In addressing the student senators sometimes living several families to the union SEIU Local 87. This issue has McDonald wrote in his email, "I am dis one home in order to make ends meet. to do with the call for renegotiations of appointed that the Senators did not more Able Co. has proposed a tiered system a proposed new contract for the workers. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

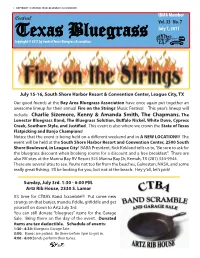

Ctba Newsletter 1107

1 COPYRIGHT © CENTRAL TEXAS BLUEGRASS ASSOCIATION IBMA Member Central Vol. 33 No. 7 Texas Bluegrass July 1, 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Central Texas Bluegrass Association July 15-16, South Shore Harbor Resort & Convention Center, League City, TX Our good friends at the Bay Area Bluegrass Association have once again put together an awesome lineup for their annual Fire on the Strings Music Festival. This year’s lineup will include Charlie Sizemore, Kenny & Amanda Smith, The Chapmans, The Lonestar Bluegrass Band, The Bluegrass Solution, Buffalo Nickel, White Dove, Cypress Creek, Southern Style, and Justified. This event is also where we crown the State of Texas Flatpicking and Banjo Champions! Notice that the event is being held on a different weekend and in A NEW LOCATION!!! The event will be held at the South Shore Harbor Resort and Convention Center, 2500 South Shore Boulevard, in League City! BABA President, Rick Kirkland tells us to, “Be sure to ask for the bluegrass discount when booking rooms for a discount and a free breakfast”. There are also RV sites at the Marina Bay RV Resort 925 Marina Bay Dr, Kemah, TX (281) 334-9944. There are several sites to see. You’re not too far from the beaches, Galveston, NASA, and some really great fishing. I’ll be looking for you, but not at the beach. Hey y’all, let’s pick! Sunday, July 3rd. 1:30 - 6:00 PM. Artz Rib House, 2330 S. Lamar It’s time for CTBA’s Band Scramble!!! Put some new strangs on that banjer, mando, fiddle, gitfiddle and get yourself on down to Artz July 3rd. -

Review and Herald for 1911

alkilik1 HMI UM IMP re %1 IWYTYTTIIV/VVIVII, 17111'1 VI I WI TIvII diejAttenf mititiad tra Vol. 88 Takoma Park Station, Washington. D. C., November 23, 1911 TAILAWAITAIII IWIT111171111 VI/ / Progress in Russia J. T. Boettcher Ps. 147: 12-15 as greetings. I have visited the Little Russian field, and also the West Russian. Thus far in both these fields about one hundred seventy persons have been added to the church during the three quarters of 1811. The Lord is working for us. To-day I saw a book printed by the Russian government in which our faith and work are described, beginning with 1844 and com- ing down to 1911. It is the best thing I ever saw in print about Seventh-day Adventists. The book is in the Russian language, with one hun- dred one folios. It contains the following : " The Seventh-day Adventists in Russia show a splen- did, live, and active work. The movement con- tinues to take in new districts in the European ‘pnci\ Asiatic Russias. They reveal a determinate zeal in their missionary efforts to win souls. The whole organization is primarily a missionary one. Eitery church-member must help forward the third angel's message, and be a witness for Christ." We praise the Lord that He even now uses the government to help forward this cause. •We are all of good courage. We lift up our heads, knowing that our salvation draweth nigh. d lr TIPTI EASY STEPS IN THE The December Number of BIBLE STORY LIFE & HEALTH Now on the press, will be ready December .r JUST THE BOOK YOU WANT FOR NOW READY YOUR CHILDREN A very entertaining and instructive volume. -

The Zyphoid Process & Great White North

The Zyphoid Process & Great White North The Zyphoid Process (sometimes stylized as The Zyphoïd Process) was probably the only band from Quebec that I actually truly adored. This melodic, chaotic, post-metalcore band featured members from various locations in the West Island of Montreal, but they practiced in the bassist’s house studio in Ile Perrot. Meeting from attending the same high school, College Charlemagne in Pierrefonds, Quebec, most of the members had crossed paths in previous bands. One of these, Deadly Awakening featured Simon Talbot on vocals, Pierre-Charles Payer on bass, Laurent Shaker and Eric Lapierre on guitars and Dave Powell on drums. Deadly Awakening played their only show in early August of 2007 at The Vault in Pierrefonds. Their set consisted of only covers; As I Lay Dying’s “Meaning in Tragedy”, Atreyu’s “Lip Gloss and Black”, Alexisonfire’s “Waterwings” and Killswitch Engage’s “My Last Serenade”. Shaker had also been jamming with another group of friends; Eric Lapierre and Raphael Sous-Leblanc on guitars with Shaker on bass. By the fall of 2007, a new band had formed featuring Simon and Raph on guitars and dual vocals, and PCP on bass. Simon was responsible for naming the new band. “The Zyphoid Process”, an alteration of “xiphoid process”, was a term he had come across during a first aid course. Musical influences came from Poison the Well, Norma Jean, The Chariot and other emocore and metalcore bands of the era. The first Zyphoid Process artwork ever created. October 2007, Nicolas Kudeljian Initially, the band continued jamming with Dave Powell on drums but this didn’t last very long. -

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik. Bobby Charles was born Robert Charles Guidry on 21st February 1938 in Abbeville, Louisiana. A native Cajun himself, he recalled that his life “changed for ever” when he re-tuned his parents’ radio set from a local Cajun station to one playing records by Fats Domino. Most successful as a songwriter, he is regarded as one of the founding fathers of swamp pop. His own vocal style was laidback and drawling. His biggest successes were songs other artists covered, such as ‘See You Later Alligator’ by Bill Haley & His Comets; ‘Walking To New Orleans’ by Fats Domino - with whom he recorded a duet of the same song in the 1990s - and ‘(I Don’t Know Why) But I Do’ by Clarence “Frogman” Henry. It allowed him to live off the song-writing royalties for the rest of his life! No albums were by him released in this period. Two other well-known compositions are ‘The Jealous Kind’, recorded by Joe Cocker, and ‘Tennessee Blues’ by Kris. Disenchanted with the music business, Bobby disappeared from the music scene in the mid-1960s but returned in 1972 with a self-titled album on the Bearsville label on which he was accompanied by Rick Danko and several other members of the Band and Dr John. Bobby later made a rare live appearance as a guest singer on stage at The Last Waltz, the 1976 farewell concert of the Band, although his contribution was cut from Martin Scorsese’s film of the event. Bobby Charles returned to the studio in later years, recording a European-only album called Clean Water in 1987.