Maritime Bluegrass: the Local Meaning of a Global Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Reference Manual

Reference Manual RRA008 | v.1.0 Contents Welcome to the Traveler Series 2 Download & Installation 3 Instrument 4 Phrases & FX 9 TACT 11 FX Rack 15 List of Articulations 16 Credits 17 License Agreement 18 1 | Page WELCOME TO THE TRAVELER SERIES Welcome to the Traveler Series, a collection of boutique sample libraries featuring traditional world instruments faithfully recorded on location from destinations around the globe. Traveler Series libraries focus on delivering a genuine purity that can only be captured where the instrument and musical style originated, preserving its true character and history. We seek out a region’s most skilled and renowned performers; amazing folks with stories and bloodlines who live and breathe traditional provincial music. We leave with an education and appreciation for their culture and the role these beautiful instruments serve (as well as a tale or two of our own). We hope our Traveler Series adds an authentic native spirit to your music. Bluegrass fiddling is a distinctive American style characterized by bold, bluesy improvisation, off-beat "chopping", and sophisticated use of double stops and old-time bowing patterns. Notes are often slid into, a technique seldom used in Celtic styles. Bluegrass fiddlers tend to ignore the rules that violinists follow: they hold the fiddle the “wrong” way and often don't use the chin & shoulder rests. We journeyed right to the heart of the Bluegrass State for our Bluegrass Fiddle – Clay City, Kentucky – to the private studio of one of the most renowned names in Bluegrass music, Rickey Wasson. Rickey hooked us up with a true Bluegrass fiddle legend, multi-instrumentalist Ronnie Stewart. -

Hallelujah Leonard Cohen

Hallelujah Leonard Cohen I've heard that there’s a secret chord That David played, and it pleased the Lord But you don't really care for music, do you? It goes like this The fourth, the fifth The minor fall, the major lift The baffled king composing Hallelujah Hallelujah x 4 You say I took the name in vain But I don't even know the name And if I did, well really, what's it to you? There's a blaze of light In every word It doesn't matter what you’ve heard The holy or the broken Hallelujah Hallelujah x 4 I did my best, it wasn't much I couldn't feel, so I tried to touch I've told the truth, I didn't come to fool you And even though it all went wrong I stand before the Lord of Song With nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah Hallelujah x 4 "Hallelujah" is a song written by Canadian singer Leonard Cohen, originally released on his album Various Positions (1984). Achieving little initial success, the song found greater popular acclaim through a recording by John Cale, which inspired a recording by Jeff Buckley. It has been viewed as a "baseline" for secular hymns. Following its increased popularity after being featured in the film Shrek (2001), many other arrangements have been performed in recordings and in concert, with over 300 versions known. The song has been used in film and television soundtracks and televised talent contests. "Hallelujah" experienced renewed interest following Cohen's death in November 2016 and appeared on many international singles charts, including entering the American Billboard Hot 100 for the first time. -

2014 Joe Val Bluegrass Festival Preview

2014 Joe Val Bluegrass Festival Preview The 29th Joe Val Bluegrass Festival is quickly approaching, February 14 -16 at the Sheraton Framingham Hotel, in Framingham, MA. The event, produced by the Boston Bluegrass Union, is one of the premier roots music festivals in the Northeast. The festival site is minutes west of Boston, just off of the Mass Pike, and convenient to travelers from throughout the region. This award winning and family friendly festival features three days of top national performers across two stages, over sixty workshops and education programs, and around the clock activities. Among the many artists on tap are The Gibson Brothers, Blue Highway, Junior Sisk, IIIrd Tyme Out, Sister Sadie featuring Dale Ann Bradley, and a special reunion performance by The Desert Rose Band. This locally produced and internationally recognized bluegrass festival, produced by the Boston Bluegrass Union, was honored in 2006 when the International Bluegrass Music Association named it "Event of the Year." In May 2012, the festival was listed by USATODAY as one of Ten Great Places to Go to Bluegrass Festivals Single day and weekend tickets are on sale now and we strongly suggest purchasing tickets in advance. Patrons will save time at the festival and guarantee themselves a ticket. Hotel rooms at the Sheraton are sold out, but overnight lodging is still available and just minutes away, at the Doubletree by Hilton, in Westborough, MA. Details on the festival, including bands, schedules, hotel information, and online ticket purchase at www.bbu.org And visit the 29th Joe Val Bluegrass Festival on Facebook for late breaking festival news. -

Charley Pride

Charley Pride 2 32 The Ultimate Hits Collection CDs Tracks A value-priced, 2 CD retrospective that surveys the biggest hits and essential fan favorites by this living Country Music legend. Charley Pride possesses one of the quintessential Country Music voices and remains well-loved as Country Music’s first and only African-American superstar with an amazing legacy of #1 hits and over 70 million records sold internationally. THE ULTIMATE HITS COLLECTION compiles recordings that represent all four decades of Pride’s legendary career-to-date, ranging from Just Between You and Me, his first Top-10 and Grammy-nominated hit from 1966, to his 2006 studio album, PRIDE AND JOY: A GOSPEL MUSIC COLLECTION. Twenty-four (24) of Pride’s Top-10 hits are represented in this amazing, 2 CD set, including Kiss An Angel Good Mornin’, the #1 crossover hit that sold over a million singles and helped Pride land the Country Music Association’s Entertainer of the Year award in 1971 and the Top Male Vocalist awards of 1971 and 1972. Track Listing Disc One Disc Two Artist Charley Pride • Just Between You And Me • Mountain Of Love Title The Ultimate Hits Collection • I Know One • Someone Loves You Honey Selection # MC05297 • Does My Ring Hurt Your Finger • I Don't Think She’s In Love Anymore UPC 826309052973 Prebook 12-16-08 • Kaw-Liga • Burgers And Fries Street Date 01-20-09 • All I Have To Offer You (Is Me) • Where Do I Put Her Memory Retail $18.98 • (I’m So) Afraid Of Losing You Again • Never Been So Loved (In All My Life) Genre Country • Is Anybody Goin’ To -

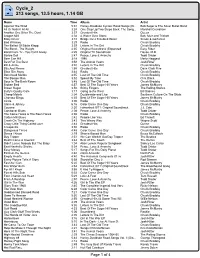

Cycle2 Playlist

Cycle_2 213 songs, 13.5 hours, 1.14 GB Name Time Album Artist Against The Wind 5:31 Harley-Davidson Cycles: Road Songs (Di... Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band All Or Nothin' At All 3:24 One Step Up/Two Steps Back: The Song... Marshall Crenshaw Another One Bites The Dust 3:37 Greatest Hits Queen Aragon Mill 4:02 A Water Over Stone Bok, Muir and Trickett Baby Driver 3:18 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel Bad Whiskey 3:29 Radio Chuck Brodsky The Ballad Of Eddie Klepp 3:39 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky The Band - The Weight 4:35 Original Soundtrack (Expanded Easy Rider Band From Tv - You Can't Alway 4:25 Original TV Soundtrack House, M.D. Barbie Doll 2:47 Peace, Love & Anarchy Todd Snider Beer Can Hill 3:18 1996 Merle Haggard Best For The Best 3:58 The Animal Years Josh Ritter Bill & Annie 3:40 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky Bits And Pieces 1:58 Greatest Hits Dave Clark Five Blow 'Em Away 3:44 Radio Chuck Brodsky Bonehead Merkle 4:35 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky The Boogie Man 3:52 Spend My Time Clint Black Boys In The Back Room 3:48 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky Broken Bed 4:57 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Brown Sugar 3:50 Sticky Fingers The Rolling Stones Buffy's Quality Cafe 3:17 Going to the West Bill Staines Cheap Motels 2:04 Doublewide and Live Southern Culture On The Skids Choctaw Bingo 8:35 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Circle 3:00 Radio Chuck Brodsky Claire & Johnny 6:16 Color Came One Day Chuck Brodsky Cocaine 2:50 Fahrenheit 9/11: Original Soundtrack J.J. -

Lone Bellow – Episode Transcript Matt: for Those Who Are Unaware of Steven Pressfield, Pressfield Is an Author of a Book Called the War of Art

THE RESISTANCE – EPISODE 18 Zach Williams of The Lone Bellow – Episode Transcript Matt: For those who are unaware of Steven Pressfield, Pressfield is an author of a book called The War of Art. It’s actually sort of our source inspirational material for the podcast, so Zach I’d love just to read a couple lines and have you riff on that, and we’ll see where it goes over the next few minutes. So Pressfield says this: “Most of us have two lives: the life we live, and the unlived life within us. And between the two stands the resistance.” Zach, I’d love to know for you, what form resistance is taking, on the verge of another album release, or even personally in other creative ways, whatever that strikes you. Zach: I think some of my base levels, I struggle with people-pleasing, and that can be with my band, that can be during a show. It’s something that I have to be aware of. So I think I needed to figure out some things going on inside me that would easily lead me to making something that I didn’t want to make, once it was all said and done, and not getting carried away just in the process of creating the music. Every single sound that you record, every single emotion that you try to capture, it all can be tied back in to one thing in someone’s soul. For me, that can easily be some sort of fear. I started writing music in 2003, and it was a very cathartic thing. -

Civilian Conservation Corps

Sandy Hook, Gateway NRA, National Park Service An Oral History Interview with Civilian Conservation Corps members, Joseph “Pappy” Whalen, Joe Czarnecki, Mike Lakomie, Hazel Feil, Peter Feil, and Andy Daino Interviewed by Elaine Harmon and Tom Hoffman, NPS June 16, 1981 Transcribed by Mary Rasa, 2012 Colorized image of CCC Camp 288, Fort Hancock, Camp Lowe, New Jersey All images courtesy NPS/Gateway NRA Editor’s notes in parenthesis ( ) (Six people were interviewed at once on audio tape. There were many times that individuals were inaudible because several conversations were taking place. Sometimes it was difficult to determine which man was speaking. If the editor could not determine the person speaking, it is written as CCC member.) EH: We have a special event today at Park Headquarters and that is the grouping together of CCC members who in fact saw the beginning of the CCC at Camp Lowe, Horseshoe Cove. Three of the seven people here with us can actually recall the early founding of the CCC. I would like to, actually our gathering today was inspired by one of the members, Mr. Joseph Whalen who came from Silver Springs, Maryland to be with us today. The remaining six people are mostly local people but who have also traveled quite a distance to be with us. Let’s introduce ourselves before we get really started. JW: I would be Joseph Whalen, Silver Springs, Maryland. That’s about it. EH: And you were known as “Pappy” Whalen. 1 JW: That was my nickname. Gee, I was so young looking. That’s why they gave it to me. -

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Outlaws & Armadillos: Country's

® COUNTRY MUSIC HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM ANNOUNCES NEXT MAJOR EXHIBITION: OUTLAWS & ARMADILLOS: COUNTRY’S ROARING ’70s The work above is by artist and illustrator Jim Franklin, who created posters for Austin’s Armadillo World Headquarters. The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum commissioned the work for its exhibit Outlaws & Armadillos. Nashville, Tenn. – Jan. 11, 2018 – Willie Nelson. Waylon Jennings. Kris Kristofferson. Jessi Colter. Bobby Bare. Jerry Jeff Walker. David Allan Coe. Cowboy Jack Clement. Tom T. Hall. Billy Joe Shaver. Guy Clark. Townes Van Zandt. Tompall Glaser. Today, all names synonymous with the word “outlaw,” but 40 years ago they started a musical revolution by creating music and a culture that shook the status quo on Music Row and cemented their place in country music history and beyond. The Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum's upcoming major exhibition, Outlaws & Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ’70s, will explore this era of cultural and artistic exchange between Nashville, Tenn., and Austin, Texas, revealing untold stories and never-seen artifacts. The exhibition, which opens May 25 for a nearly three-year run, will explore the complicated, surprising relationship between the two cities. While the smooth Nashville Sound of the late 1950s and ’60s was commercially successful, some artists, such as Nelson and Jennings, found the Music Row recording model creatively stifling. By the early 1970s, those artists could envision a music industry in which they would write, sing and produce their own music. At the same time, Austin was gaining national attention as a thriving music center with a countercultural outlook.