Britain and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Royal African: Or, Memoirs of the Young Prince of Annamaboe

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com THE Royal African? MEMO IRS ; OF THE Young Prince of Annamaboe. Comprehending A distinct Account of his Country and Family ; his elder Brother's Voyage to France, and Recep tion there ; the Manner in which himself was confided by his Father to the Captain who sold him ; his Condition while a Slave in Barbadoes ; the true Cause of his being redeemed ; his Voy age from thence; and Reception here in England. Interspers'd throughout / 4 With several Historical Remarks on the Com merce of the European Nations, whose Subjects fre quent the Coast of Guinea. To which is prefixed A LETTER from thdr; Author to a Person of Distinction, in Reference to some natural Curiosities in Africa ; as well as explaining the Motives which induced him to compose these Memoirs. — . — — t Othello shews the Muse's utmost Power, A brave, an honest, yet a hapless Moor. In Oroonoko lhines the Hero's Mind, With native Lustre by no Art resin 'd. Sweet Juba strikes us but with milder Charms, At once renown'd for Virtue, Love, and Arms. Yet hence might rife a still more moving Tale, But Shake/pears, Addisons, and Southerns fail ! LONDON: Printed for W. Reeve, at Sha&ejpear's Head, Flectsireet ; G. Woodfall, and J. Barnes, at Charing- Cross; and at the Court of Requests. /: .' . ( I ) To the Honourable **** ****** Qs ****** • £#?*, Esq; y5T /j very natural, Sir, /£æ/ ><?a should be surprized at the Accounts which our News- Papers have given you, of the Appearance of art African Prince in England under Circumstances of Distress and Ill-usage, which reflecl very highly upon us as a People. -

Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18Th Century James Buckwalter Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research Creative Activity - Documents and Creativity 4-21-2010 Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18th Century James Buckwalter Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/lib_awards_2010_docs Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Buckwalter, James, "Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18th Century" (2010). 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & Creative Activity - Documents. 1. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/lib_awards_2010_docs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research and Creativity at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & Creative Activity - Documents by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. James Buckwalter Booth Library Research Award Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18th Century My research has focused on slave insurrections on board British ships in the early 18th century and their perceptions both in government and social circles. In all, it uncovers the stark differences in attention given to shipboard insurrections, ranging from significant concern in maritime circles to near ignorance in government circles. Moreover, the nature of discourse concerning slave shipboard insurrections differs from Britons later in the century, when British subjects increasingly began to view the slave trade as not only morally reprehensible, but an area in need of political reform as well. -

Triangular Trade and the Middle Passage

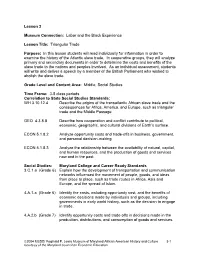

Lesson 3 Museum Connection: Labor and the Black Experience Lesson Title: Triangular Trade Purpose: In this lesson students will read individually for information in order to examine the history of the Atlantic slave trade. In cooperative groups, they will analyze primary and secondary documents in order to determine the costs and benefits of the slave trade to the nations and peoples involved. As an individual assessment, students will write and deliver a speech by a member of the British Parliament who wished to abolish the slave trade. Grade Level and Content Area: Middle, Social Studies Time Frame: 3-5 class periods Correlation to State Social Studies Standards: WH 3.10.12.4 Describe the origins of the transatlantic African slave trade and the consequences for Africa, America, and Europe, such as triangular trade and the Middle Passage. GEO 4.3.8.8 Describe how cooperation and conflict contribute to political, economic, geographic, and cultural divisions of Earth’s surface. ECON 5.1.8.2 Analyze opportunity costs and trade-offs in business, government, and personal decision-making. ECON 5.1.8.3 Analyze the relationship between the availability of natural, capital, and human resources, and the production of goods and services now and in the past. Social Studies: Maryland College and Career Ready Standards 3.C.1.a (Grade 6) Explain how the development of transportation and communication networks influenced the movement of people, goods, and ideas from place to place, such as trade routes in Africa, Asia and Europe, and the spread of Islam. 4.A.1.a (Grade 6) Identify the costs, including opportunity cost, and the benefits of economic decisions made by individuals and groups, including governments in early world history, such as the decision to engage in trade. -

The Slow Death of Slavery in Nineteenth Century Senegal and the Gold Coast

That Most Perfidious Institution: The slow death of slavery in nineteenth century Senegal and the Gold Coast Trevor Russell Getz Submitted for the degree of PhD University of London, School or Oriental and African Studies ProQuest Number: 10673252 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673252 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract That Most Perfidious Institution is a study of Africans - slaves and slave owners - and their central roles in both the expansion of slavery in the early nineteenth century and attempts to reform servile relationships in the late nineteenth century. The pivotal place of Africans can be seen in the interaction between indigenous slave-owning elites (aristocrats and urban Euro-African merchants), local European administrators, and slaves themselves. My approach to this problematic is both chronologically and geographically comparative. The central comparison between Senegal and the Gold Coast contrasts the varying impact of colonial policies, integration into the trans-Atlantic economy; and, more importantly, the continuity of indigenous institutions and the transformative agency of indigenous actors. -

The Transatlantic Slave Trade and the Creation of the English Weltanschauung, 1685-1710

The Transatlantic Slave Trade and the Creation of the English Weltanschauung, 1685-1710 James Buckwalter James Buckwalter, a member of Phi Alpha Theta, is a senior majoring in History with a Secondary Education Teaching Certificate from Tinley Park, Illinois. He wrote this paper for an independent study course with Dr. Key during the fall of 2008. At the turn of the-eighteenth century, the English public was confronted with numerous and conflicting interpretations of Africans, slavery, and the slave trade. On the one hand, there were texts that glorified the institution of slavery. Gabriel de Brémond’s The Happy Slave, which was translated and published in London in 1686, tells of a Roman, Count Alexander, who is captured off the coast of Tunis by “barbarians,” but is soon enlightened to the positive aspects of slavery, such as, being “lodged in a handsome apartment, where the Baffa’s Chyrurgions searched his Wounds: And…he soon found himself better.”58 On the other hand, Bartolomé de las Casas’ Popery truly display'd in its bloody colours (written in 1552, but was still being published in London in 1689), displays slavery in the most negative light. De las Casas chastises the Spaniards’ “bloody slaughter and destruction of men,” condemning how they “violently forced away Women and Children to make them slaves, and ill-treated them, consuming and wasting their food.”59 Moreover, Thomas Southerne’s adaptation of Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko in 1699 displays slavery in a contradictory light. Southerne condemns Oroonoko’s capture as a “tragedy,” but like Behn’s version, Oroonoko’s royalty complicates the matter, eventually causing the author to show sympathy for the enslaved African prince. -

Mn WORKING PAPERS in ECONOMIC HISTORY

rm London School of Economics & Political Science mn WORKING PAPERS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY 'PAWNS WILL LIVE WHEN SLAVES IS APT TO DYE': CREDIT, SLAVING AND PAWNSHIP AT OLD CALABAR IN THE ERA OF THE SLAVE TRADE Paul E. Lovejoy and David Richardson Number: 38/97 November 1997 Working Paper No. 38/97 (Pawns will live when slaves is apt to dye': Credit, Slaving and Pawnship at Old Calabar in the era of the Slave Trade Paul E. Lovejoy and David Richardson ~P.E. LovejoylDavid Richardson Department of Economic History London School of Economics November 1997 Paul E. Lovejoy and David Richardson, Clo Department of Economic History, London School of Economics, Houghton Street, London. WC2A 2AE. Telephone: +44 (0)1719557084 Fax: +44 (0)171 9557730 Additional copies of this working paper ar~ available at a cost of £2.50. Cheques should be made payable to 'Department of Economic History, LSE' and sent to the Economic History Department Secretary, LSE, Houghton Street, London.WC2A 2AE, U.K. Acknowledgement This paper was presented at a meeting of the Seminar on the Comparative Economic History of Africa, Asia and Latin America at LSE earlier in 1997. The Department of Economic History acknowledges the financial support from the Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines (STICERD), which made the seminar possible. Note on the authors Paul Lovejoy is Distinguished Research Professor at York University, Canada. He is the author of many essays, several books, and has edited several collections of papers: on African economic history and the history of slavery. His books include Transformations in Slavery: a history ofslavery in Africa (1983) and (with Jan Hogendorn), Slow Death for Slavery: the course ofabolition in Northern Nigeria, 1897-1936 (1993). -

(Re)Financing the Slave Trade with the Royal African Company in the Boom Markets of 17201

CENTRE FOR DYNAMIC MACROECONOMIC ANALYSIS WORKING PAPER SERIES CDMA11/14 (Re)financing the Slave Trade with the Royal African Company in the Boom Markets of 17201 Gary S. Shea2 University of St Andrews OCTOBER 2011 ABSTRACT In 1720, subscription finance and its attendant financial policies were highly successful for the Royal African Company. The values of subscription shares are easily understandable using standard elements of derivative security pricing theory. Sophisticated provision for protection of shareholder wealth made subscription finance successful; its parallels with modern innovated securities are demonstrated. A majority of Company shareholders participated in the re-financing, but could provide only a small portion of the new equity required. The re-financing attracted to the subscription an investment class that was strongly composed of parliamentary and aristocratic elements, but appeared to be only weakly attractive to persons who had already invested in the East India Company and was not attractive at all to Bank of England investors or to those persons who were investing in newly created marine insurance companies. Subsequent trade in subscription shares was more intense than was other share trading during the South Sea Bubble, but the trade was only lightly served by financial intermediaries. Professional financial intermediaries did not form densely connected networks of trade that were the hallmarks of Bank of England and East India Company share trading. The re-financing launched an only briefly successful revival of the Company’s slave trade. JEL Classification: N23, G13. Keywords: South Sea Company; South Sea Bubble; goldsmith bankers; subscription shares; call options; derivatives; installment receipts; innovated securities; networks. -

AMHE Newsletter Spring 2020 April 27 Haitian Medical Association Abroad Association Medicale Haïtienne À L'étranger Newsletter # 276

AMHE Newsletter spring 2020 april 27 Haitian Medical Association Abroad Association Medicale Haïtienne à l'Étranger Newsletter # 276 AMHE NEWSLETTER Editor in Chief: Maxime J-M Coles, MD Editorial Board: Rony Jean Mary, MD Reynald Altema, MD Technical Adviser: Jacques Arpin The Longevity of a Total Hip Replacement Maxime Coles MD In this number - Words of the Editor, Maxime Coles,MD - You need to know the difference in symptoms: - La chronique de Rony Jean-Mary,M.D. - From The New York Times: - La chronique de Reynald Altéma,M.D. - Décès - Chronicle of Slave rebellions in the Americas. - And more... 2 In face of a patient presenting with a painful hip other causing stiffness and later pain and joint enabling him to ambulate and forcing the inability to bear weight and ambulate. use of external supports or a wheelchair, one 2- Autoimmune diseases like Rheumatoid can understand how daily living activities can arthritis in which the synovial membrane affect life. The hip become stiff and painful become diseased, inflamed or thickened, rendering any task requesting mobility, difficult. damaging the cartilage in allowing a loss The individual contemplating such procedure of joint surface. This kind of process often report difficulties in wearing socks represents a group of disorders called because of inability to cross their legs. Medications which have in the past relieved the inflammatory arthritis. symptoms, ceased to benefit the patient. A hip 3- Injuries to the hip joint following a replacement become the best option to restore traumatic event like a fracture dislocation, functionality. can damage the articular cartilage of the Anecdotally, the first total hip replacement was hip joint and lead to stiffness, pain and performed in the mid-20th century. -

Museum Gallery Archive

Museum Transatlantic Slavery and Abolition timeline Olaudah Equiano is in While at Cambridge, Thomas Plymouth, employed by Clarkson writes an essay the government to assist in Gallery about slavery buying supplies for three This timeline is based upon research carried out by curator Len Pole for the exhibition Its subject is Is it lawful to ships setting out for ‘The Land A fourth fleet sails out of of Freedom’, in Sierra Leone Plymouth in October, including make slaves of others against Archive ‘Human Cargo’ at Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery. the Jesus of Lubeck, with their will? It is published and Hawkins in command. Francis creates great interest, not least While in Plymouth, Hrake is given command of a ship in William Wilberforce MP Equiano is sacked from The Piracy Act is broadened to captured off the coast of Guinea this job after exposing include slave trading, but it remains corruption and ill impossible for the Anti-Slavery Multiple revolts in treatment of the migrants. Squadron to board ships flying the West Indies This exhibition and its learning programme formed part of the nationwide Abolition 200 events, exhibitions and educational Jonathan Strong is prevented from The Zong case comes to court He was subsequently Rebellion in Demerara (now Guyana) other nations’ flags - the freedom being sold back into slavery twice, thanks to the efforts of the compensated £50 Over 9,000 thousand rebel slaves of the seas is paramount Britain commemorates 200th anniversary projects organised to mark the 200th anniversary of the passing of the 1807 Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. -

Trust and the African Slave Trade: a Study of the African-European Relationship of Trust During the Height of Trade 1600-1800

Trust and the African Slave Trade: A Study of the African-European Relationship of Trust during the height of trade 1600-1800 Senior Honors History Thesis Chantel Priolo April 1, 2008 Advisors: Pier Larson Mary Ryan 1 I. Introduction It was three o’clock on June 18 in the year 1727. English slave trader William Snelgrave was beckoned by a native messenger of the great King Agaja while trading in Jakin. The King had appointed to meet with Snelgrave to settle negotiations over payments for permission to trade, slave prices, and the details of the contents of Snelgrave’s cargo.1 Upon arriving at the court, Snelgrave and company were introduced to “the king” who was seated richly dressed and cross-legged on a silk carpet spread on the ground. Upon approaching the king, his Majesty asked them how they fared and ordered that his guests should be placed near him. Accordingly, fine mats were set on the ground and, although an uncomfortable posture for the Englishmen, they proceeded to sit. The King ordered his interpreters to ask Snelgrave what he had desired of him. Snelgrave answered that it was his business to trade, relying upon his majesty’s goodness to give him a “quick dispatch and fill his ship with negroes.”2 If the request was fulfilled, Snelgrave assured the King he would return to his own country and make known how great and powerful a king he had seen. To this, the king replied to the interpreter that his desires should be fulfilled, but the first business to be settled was his customs.3 He added that the best way to make trade flourish was to impose early trading fees, to protect both the Europeans and his kingdom from thievery of the natives. -

'Freedom's Debt: the Royal African Company and the Politics of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1672-1752' (X-H-Albion)

H-Slavery Review: Rhoden on Pettigrew, 'Freedom's Debt: The Royal African Company and the Politics of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1672-1752' (x-h-albion) Discussion published by Temp Editor Peter Knupfer on Monday, February 16, 2015 [Ed. note (PBK): A new review from our friends at h-albion.] Review published on Monday, February 16, 2015 Author: William A. Pettigrew Reviewer: Nancy L. Rhoden Rhoden on Pettigrew, 'Freedom's Debt: The Royal African Company and the Politics of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1672-1752' William A. Pettigrew. Freedom's Debt: The Royal African Company and the Politics of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1672-1752. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. 272 pp. $45.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-4696-1181-5. Reviewed by Nancy L. Rhoden (University of Western Ontario) Published on H-Albion (February, 2015) Commissioned by Jeffrey R. Wigelsworth William Pettigrew’s study of the Royal African Company (RAC) from its charter to its final demise looks at “the slave-trade protagonists, analyzing the ideas, the disputes, the compromises—in short, the politics—that established England’s involvement in and later dominance of the transatlantic slave trade” (p. 4). This is a deeply researched, persuasive study on the political disputes between the RAC and what the author calls the independent slave traders who opposed the RAC’s monopoly and were victorious by 1712 in deregulating Britain’s slave trade. Pettigrew argues that independent traders were more politically astute than supporters of the RAC, more effective in their lobbying and pamphleteering, and more savvy about the ways British politics had changed following the Glorious Revolution. -

Institute of Contemporary Arts

Institute of Contemporary Arts PRESS RELEASE 3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73 Cameron Rowland 29 January – 12 April 2020 Opening: Tuesday 28 January, 6–8pm Press View: Tuesday 28 January, 10am–12pm For further information, please contact: Bridie Hindle, ICA, Press Manager [email protected] / +44 (0)20 7766 1409 Miles Evans PR [email protected] / +44 (0)7812 985 993 www.ica.art The Mall London SW1Y 5AH +44 (0)20 7930 0493 3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73 Cameron Rowland WHEREAS divers Persons are holden in Slavery within divers of His Majesty’s Colonies, and it is just and expedient that all such Persons should be manumitted and set free, and that a reasonable Compensation should be made to the Persons hitherto entitled to the Services of such Slaves for the Loss which they will incur by being deprived of their Right to such Services. – An Act for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Colonies; for promoting the Industry of the manumitted Slaves; and for compensating the Persons hitherto entitled to the Services of such Slaves, 1833. 3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73 Abolition preserved the property established by slavery. This property is maintained in the market and the state. “The Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 encouraged a version of overseas empire based upon formal imperial institutions such as monopoly trading companies. The Royal African Company was designed to be central to this system.”1 In 1660, Charles II chartered the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa to dig for gold in the Gambia.