The Intimacies of Four Continents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Royal African: Or, Memoirs of the Young Prince of Annamaboe

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com THE Royal African? MEMO IRS ; OF THE Young Prince of Annamaboe. Comprehending A distinct Account of his Country and Family ; his elder Brother's Voyage to France, and Recep tion there ; the Manner in which himself was confided by his Father to the Captain who sold him ; his Condition while a Slave in Barbadoes ; the true Cause of his being redeemed ; his Voy age from thence; and Reception here in England. Interspers'd throughout / 4 With several Historical Remarks on the Com merce of the European Nations, whose Subjects fre quent the Coast of Guinea. To which is prefixed A LETTER from thdr; Author to a Person of Distinction, in Reference to some natural Curiosities in Africa ; as well as explaining the Motives which induced him to compose these Memoirs. — . — — t Othello shews the Muse's utmost Power, A brave, an honest, yet a hapless Moor. In Oroonoko lhines the Hero's Mind, With native Lustre by no Art resin 'd. Sweet Juba strikes us but with milder Charms, At once renown'd for Virtue, Love, and Arms. Yet hence might rife a still more moving Tale, But Shake/pears, Addisons, and Southerns fail ! LONDON: Printed for W. Reeve, at Sha&ejpear's Head, Flectsireet ; G. Woodfall, and J. Barnes, at Charing- Cross; and at the Court of Requests. /: .' . ( I ) To the Honourable **** ****** Qs ****** • £#?*, Esq; y5T /j very natural, Sir, /£æ/ ><?a should be surprized at the Accounts which our News- Papers have given you, of the Appearance of art African Prince in England under Circumstances of Distress and Ill-usage, which reflecl very highly upon us as a People. -

From David Walker to President Obama: Tropes of the Founding Fathers in African American Discourses of Democracy, Or the Legacy of Ishmael

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Faculty Publications Department of English 2012 From David Walker to President Obama: Tropes of the Founding Fathers in African American Discourses of Democracy, or The Legacy of Ishmael Elizabeth J. West Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation West, Elizabeth J., "From David Walker to President Obama: Tropes of the Founding Fathers in African American Discourses of Democracy, or The Legacy of Ishmael" (2012). English Faculty Publications. 15. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_facpub/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “From David Walker to President Obama: Tropes of the Founding Fathers in African American Discourses of Democracy, or The Legacy of Ishmael” Dr. Elizabeth J. West Dept. of English—Georgia State Univ. Nov. 2010 “Call me Ishmael,” Herman Melville’s elusive narrator instructs readers. The central voice in the lengthy saga called Moby Dick, he is a crewman aboard the Pequod. This Ishmael reveals little about himself, and he does not seem altogether at home. As the narrative unfolds, this enigmatic Ishmael seems increasingly out of sorts in the world aboard the Pequod. He finds himself at sea working with and dependent on fellow seamen, who are for the most part, strange and frightening and unreadable to him. -

Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18Th Century James Buckwalter Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research Creative Activity - Documents and Creativity 4-21-2010 Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18th Century James Buckwalter Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/lib_awards_2010_docs Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Buckwalter, James, "Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18th Century" (2010). 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & Creative Activity - Documents. 1. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/lib_awards_2010_docs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research and Creativity at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & Creative Activity - Documents by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. James Buckwalter Booth Library Research Award Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18th Century My research has focused on slave insurrections on board British ships in the early 18th century and their perceptions both in government and social circles. In all, it uncovers the stark differences in attention given to shipboard insurrections, ranging from significant concern in maritime circles to near ignorance in government circles. Moreover, the nature of discourse concerning slave shipboard insurrections differs from Britons later in the century, when British subjects increasingly began to view the slave trade as not only morally reprehensible, but an area in need of political reform as well. -

Slaves of the State: Black Incarceration from the Chain Gang

• CHAPTER 2 • “Except as Punishment for a Crime” The Thirteenth Amendment and the Rebirth of Chattel Imprisonment Slavery was both the wet nurse and bastard offspring of liberty. — Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection It is true, that slavery cannot exist without law . — Joseph Bradley, The Civil Rights Cases nyone perusing the advertisements section of local newspapers such as the Annapolis Gazette in Maryland, during December 1866, wouldA have come across the following notices: Public Sale— The undersigned will sell at the Court House Door in the city of Annapolis at 12 o’clock M., on Saturday 8th December, 1866, A Negro man named Richard Harris, for six months, convicted at the October term, 1866, of the Anne Arundel County Circuit Court for larceny and sentenced by the court to be sold as a slave. Terms of sale— cash. WM. Bryan, Sheriff Anne Arundel County. Dec. 8, 1866 Public Sale— The undersigned will offer for Sale, at the Court House Door, in the city of Annapolis, at eleven O’Clock A.M., on Saturday, 22d of December, a negro [sic] man named John Johnson, aged about Forty years. The said negro was convicted the October Term, 1866, of the Circuit Court for Anne Arundel county, for; • 57 • This content downloaded from 71.114.106.89 on Sun, 23 Aug 2020 20:24:23 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Childs.indd 57 17/12/2014 12:56:10 PM 58 “EXCEPT AS PUNISHMENT FOR A CRIME” Larceny, and sentenced to be sold, in the State, for the term of one year, from the 12th of December, 1866. -

Slave Narratives Redefine Womanhood in Nineteenth-Century America Candice E

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research Spring 2002 Escaping the auction block and rejecting the pedestal of virtue : slave narratives redefine womanhood in nineteenth-century America Candice E. Renka Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Renka, Candice E., "Escaping the auction block and rejecting the pedestal of virtue : slave narratives redefine omw anhood in nineteenth-century America" (2002). Honors Theses. Paper 326. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND LIBRARIES I \\I \\II \\\II\\\ I\\\\\\ II 111\I \\II ~I\~\\3 3082 I\\~\\\\\\\\\\\ 00748 1921I\~ Escaping the Auction Block and Rejecting the Pedestal of Virtue: Slave Narratives Redefine Womanhood in Nineteenth-Century America Candice E. Renka Honors Thesis Department of English University of Richmond Dr Thomas Allen, Thesis Director Spring 2002 The signatures below certify that with this essay Candice Renka has satisfied the thesis requirement for Honors in English. (Dr Thomas Allen, thesis director) (Dr Robert Nelson, English honors coordinator) Black women's slave narratives bring to the forefront the paradoxes of antebellum America's political and moral ideologies. These autobiographies criticize the dichotomous gender roles that were widely accepted in the nineteenth century United States. Women's slave narratives perceive the exclusion of women of color and women of the working class from the prevailing model of womanhood as indicative of an inadequate conceptual framework for understanding female personhood. -

Slavery Past and Present

fact sheet Slavery past and present Right: Slaves being forced below What is Anti-Slavery International? deck. Despite the fact that many slaves were chained for the voyage it The first organised anti-slavery is estimated that a rebellion occurred societies appeared in Britain in the on one out of every eight slave ships 1780s with the objective of ending that crossed the Atlantic. the slave trade. For many people, this is the image In 1807 the British slave trade was that comes to mind when they hear abolished by Parliament and it the word slavery. We think of the became illegal to buy and sell buying and selling of people, their slaves although people could shipment from one continent to still own them. In 1833 Parliament another and the abolition of the finally abolished slavery itself, trade in the early 1800s. Even if we both in Britain and throughout know little about the slave trade, the British Empire. we think of it as part of our history rather than our present. In 1839 the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society was created, In fact, the slave trade continues to representing a new organisation for have an impact today. Its legacies the new chapter of the anti-slavery include racism, discrimination Mary Prince struggle. It gave inspiration to the and the development and under- abolitionist movement in the United development of communities and “Oh the horrors of slavery! - States and Brazil, and contributed countries affected by the trade. How the thought of it pains my to the drawing up of international And slavery itself is not a thing of heart! But the truth ought to standards on slavery. -

Triangular Trade and the Middle Passage

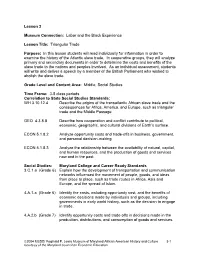

Lesson 3 Museum Connection: Labor and the Black Experience Lesson Title: Triangular Trade Purpose: In this lesson students will read individually for information in order to examine the history of the Atlantic slave trade. In cooperative groups, they will analyze primary and secondary documents in order to determine the costs and benefits of the slave trade to the nations and peoples involved. As an individual assessment, students will write and deliver a speech by a member of the British Parliament who wished to abolish the slave trade. Grade Level and Content Area: Middle, Social Studies Time Frame: 3-5 class periods Correlation to State Social Studies Standards: WH 3.10.12.4 Describe the origins of the transatlantic African slave trade and the consequences for Africa, America, and Europe, such as triangular trade and the Middle Passage. GEO 4.3.8.8 Describe how cooperation and conflict contribute to political, economic, geographic, and cultural divisions of Earth’s surface. ECON 5.1.8.2 Analyze opportunity costs and trade-offs in business, government, and personal decision-making. ECON 5.1.8.3 Analyze the relationship between the availability of natural, capital, and human resources, and the production of goods and services now and in the past. Social Studies: Maryland College and Career Ready Standards 3.C.1.a (Grade 6) Explain how the development of transportation and communication networks influenced the movement of people, goods, and ideas from place to place, such as trade routes in Africa, Asia and Europe, and the spread of Islam. 4.A.1.a (Grade 6) Identify the costs, including opportunity cost, and the benefits of economic decisions made by individuals and groups, including governments in early world history, such as the decision to engage in trade. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the History of Mary Prince a West Indian

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The History of Mary Prince A West Indian Slave Related by Herself by Mary Prince The History of Mary Prince A West Indian Slave Related by Herself by Mary Prince. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #5f146380-c433-11eb-9c3e-9334eb139672 VID: #(null) IP: 188.246.226.140 Date and time: Thu, 03 Jun 2021 06:17:28 GMT. The History of Mary Prince A West Indian Slave Related by Herself by Mary Prince. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #5f16d480-c433-11eb-9dcd-f7109d6e9abc VID: #(null) IP: 188.246.226.140 Date and time: Thu, 03 Jun 2021 06:17:28 GMT. 'They bought me as a butcher would a calf or a lamb' No images survive of Mary Prince herself, but this is the photo that has often been used to illustrate her story. No images survive of Mary Prince herself, but this is the photo that has often been used to illustrate her story. Mary Prince may have been the only Caribbean woman ever to come to Britain hopeful about the weather. -

The Reading Guide

Abolition as a Global Enterprise Readings: Mary Prince, The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave (Related by Herself). ed. Sara Salih. New York: Penguin, 2001. [first published 1831, edited by Susanna Strickland] Note: Read the narrative itself and the appendices. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point,” (Boston) Liberty Bell, 1848 http://loki.stockton.edu/~kinsellt/projects/runawayslave/storyReader$10.html or http://classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/ebbrowning/bl-ebbrown-runaway-1.htm Secondary scholarship: Baumgartner, Barbara. “The Body as Evidence: Resistance, Collaboration, and Appropriation in ‘The History of Mary Prince.’” Callaloo 24.1 (Winter 2001): 253-75. Marjorie Stone, “Elizabeth Barrett Browning and the Garrisonians: ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’, the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, and Abolitionist Discourse in the Liberty Bell.” Victorian Women Poets. Ed. Alison Chapman. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2003. 33-55. This text is available on e-college. Alan Rice, “Dramatising the Black Atlantic: Live Action Projects in Classrooms,” from Hughes and Robbins, TT Marjorie Stone, “Frederick Douglass, Maria Weston Chapman, and Harriet Martineau: Atlantic Abolitionist Networks and Transatlanticism’s Binaries,” from Hughes and Robbins, TT [Note: As of 8/29, we are still awaiting permission from Professor Stone to share her draft. We’ll keep you posted. At this point, it is not available on the workspace.] I. Guest presentation: Graduate Student Larisa Asaeli II. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, “Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” The syllabus gives two websites where you can find “Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point,” but we encourage you to read the poem in the Liberty Bell itself, since this was the first, and transatlantic publication venue, for the poem. -

Las Vegas, Nevada

2021 Toyota U.S. Figure Skating Championships January 11-21, 2021 Las Vegas | The Orleans Arena Media Information and Story Ideas The U.S. Figure Skating Championships, held annually since 1914, is the nation’s most prestigious figure skating event. The competition crowns U.S. champions in ladies, men’s, pairs and ice dance at the senior and junior levels. The 2021 U.S. Championships will serve as the final qualifying event prior to selecting and announcing the U.S. World Figure Skating Team that will represent Team USA at the ISU World Figure Skating Championships in Stockholm. The marquee event was relocated from San Jose, California, to Las Vegas late in the fall due to COVID-19 considerations. San Jose meanwhile was awarded the 2023 Toyota U.S. Championships, marking the fourth time that the city will host the event. Competition and practice for the junior and Championship competitions will be held at The Orleans Arena in Las Vegas. The event will take place in a bubble format with no spectators. Las Vegas, Nevada This is the first time the U.S. Championships will be held in Las Vegas. The entertainment capital of the world most recently hosted 2020 Guaranteed Rate Skate America and 2019 Skate America presented by American Cruise Lines. The Orleans Arena The Orleans Arena is one of the nation’s leading mid-size arenas. It is located at The Orleans Hotel and Casino and is operated by Coast Casinos, a subsidiary of Boyd Gaming Corporation. The arena is the home to the Vegas Rollers of World Team Tennis since 2019, and plays host to concerts, sporting events and NCAA Tournaments. -

Gender, Race, and Empire in Caribbean Indenture Narratives

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 The Ties that Bind: Gender, Race, and Empire in Caribbean Indenture Narratives Alison Joan Klein Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/582 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE TIES THAT BIND: GENDER, RACE, AND EMPIRE IN CARIBBEAN INDENTURE NARRATIVES by ALISON KLEIN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York. 2015 © 2015 ALISON JOAN KLEIN All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ashley Dawson __________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Mario DiGangi __________________ Date Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii THE TIES THAT BIND: GENDER, RACE, AND EMPIRE IN CARIBBEAN INDENTURE NARRATIVES by ALISON KLEIN Adviser: Professor Ashley Dawson This dissertation traces the ways that oppressive gender roles and racial tensions in the Caribbean today developed out of the British imperial system of indentured labor. Between 1837 and 1920, after slavery was abolished in the British colonies and before most colonies achieved independence, approximately 750,000 laborers, primarily from India and China, traveled to the Caribbean under indenture. -

The Slow Death of Slavery in Nineteenth Century Senegal and the Gold Coast

That Most Perfidious Institution: The slow death of slavery in nineteenth century Senegal and the Gold Coast Trevor Russell Getz Submitted for the degree of PhD University of London, School or Oriental and African Studies ProQuest Number: 10673252 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673252 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract That Most Perfidious Institution is a study of Africans - slaves and slave owners - and their central roles in both the expansion of slavery in the early nineteenth century and attempts to reform servile relationships in the late nineteenth century. The pivotal place of Africans can be seen in the interaction between indigenous slave-owning elites (aristocrats and urban Euro-African merchants), local European administrators, and slaves themselves. My approach to this problematic is both chronologically and geographically comparative. The central comparison between Senegal and the Gold Coast contrasts the varying impact of colonial policies, integration into the trans-Atlantic economy; and, more importantly, the continuity of indigenous institutions and the transformative agency of indigenous actors.