The Angolan Connection and Slavery in Virginia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181

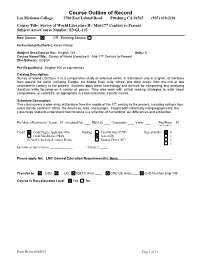

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181 Course Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Subject Area/Course Number: ENGL-145 New Course OR Existing Course Instructor(s)/Author(s): Karen Nakaji Subject Area/Course No.: English 145 Units: 3 Course Name/Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Discipline(s): English Pre-Requisite(s): English 100 or equivalency Catalog Description: Survey of World Literature II is a comparative study of selected works, in translation and in English, of literature from around the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and other areas, from the mid or late seventeenth century to the present. Students apply basic terminology and devices for interpreting and analyzing literature while focusing on a variety of genres. They also work with critical reading strategies to write about comparisons, or contrasts, as appropriate in a baccalaureate, transfer course. Schedule Description: This class covers a wide array of literature from the middle of the 17th century to the present, including authors from every literate continent: Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Taught both historically and geographically, the class helps students understand how literature is a reflection of humankind, our differences and similarities. Hrs/Mode of Instruction: Lecture: 54 Scheduled Lab: ____ HBA Lab: ____ Composition: ____ Activity: ____ Total Hours 54 (Total for course) Credit Credit Degree Applicable -

The Royal African: Or, Memoirs of the Young Prince of Annamaboe

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com THE Royal African? MEMO IRS ; OF THE Young Prince of Annamaboe. Comprehending A distinct Account of his Country and Family ; his elder Brother's Voyage to France, and Recep tion there ; the Manner in which himself was confided by his Father to the Captain who sold him ; his Condition while a Slave in Barbadoes ; the true Cause of his being redeemed ; his Voy age from thence; and Reception here in England. Interspers'd throughout / 4 With several Historical Remarks on the Com merce of the European Nations, whose Subjects fre quent the Coast of Guinea. To which is prefixed A LETTER from thdr; Author to a Person of Distinction, in Reference to some natural Curiosities in Africa ; as well as explaining the Motives which induced him to compose these Memoirs. — . — — t Othello shews the Muse's utmost Power, A brave, an honest, yet a hapless Moor. In Oroonoko lhines the Hero's Mind, With native Lustre by no Art resin 'd. Sweet Juba strikes us but with milder Charms, At once renown'd for Virtue, Love, and Arms. Yet hence might rife a still more moving Tale, But Shake/pears, Addisons, and Southerns fail ! LONDON: Printed for W. Reeve, at Sha&ejpear's Head, Flectsireet ; G. Woodfall, and J. Barnes, at Charing- Cross; and at the Court of Requests. /: .' . ( I ) To the Honourable **** ****** Qs ****** • £#?*, Esq; y5T /j very natural, Sir, /£æ/ ><?a should be surprized at the Accounts which our News- Papers have given you, of the Appearance of art African Prince in England under Circumstances of Distress and Ill-usage, which reflecl very highly upon us as a People. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18Th Century James Buckwalter Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research Creative Activity - Documents and Creativity 4-21-2010 Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18th Century James Buckwalter Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/lib_awards_2010_docs Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Buckwalter, James, "Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18th Century" (2010). 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & Creative Activity - Documents. 1. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/lib_awards_2010_docs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research and Creativity at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2010 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & Creative Activity - Documents by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. James Buckwalter Booth Library Research Award Shipboard Insurrections, the British Government and Anglo-American Society in the Early 18th Century My research has focused on slave insurrections on board British ships in the early 18th century and their perceptions both in government and social circles. In all, it uncovers the stark differences in attention given to shipboard insurrections, ranging from significant concern in maritime circles to near ignorance in government circles. Moreover, the nature of discourse concerning slave shipboard insurrections differs from Britons later in the century, when British subjects increasingly began to view the slave trade as not only morally reprehensible, but an area in need of political reform as well. -

Triangular Trade and the Middle Passage

Lesson 3 Museum Connection: Labor and the Black Experience Lesson Title: Triangular Trade Purpose: In this lesson students will read individually for information in order to examine the history of the Atlantic slave trade. In cooperative groups, they will analyze primary and secondary documents in order to determine the costs and benefits of the slave trade to the nations and peoples involved. As an individual assessment, students will write and deliver a speech by a member of the British Parliament who wished to abolish the slave trade. Grade Level and Content Area: Middle, Social Studies Time Frame: 3-5 class periods Correlation to State Social Studies Standards: WH 3.10.12.4 Describe the origins of the transatlantic African slave trade and the consequences for Africa, America, and Europe, such as triangular trade and the Middle Passage. GEO 4.3.8.8 Describe how cooperation and conflict contribute to political, economic, geographic, and cultural divisions of Earth’s surface. ECON 5.1.8.2 Analyze opportunity costs and trade-offs in business, government, and personal decision-making. ECON 5.1.8.3 Analyze the relationship between the availability of natural, capital, and human resources, and the production of goods and services now and in the past. Social Studies: Maryland College and Career Ready Standards 3.C.1.a (Grade 6) Explain how the development of transportation and communication networks influenced the movement of people, goods, and ideas from place to place, such as trade routes in Africa, Asia and Europe, and the spread of Islam. 4.A.1.a (Grade 6) Identify the costs, including opportunity cost, and the benefits of economic decisions made by individuals and groups, including governments in early world history, such as the decision to engage in trade. -

Reading the Remains of the 17Th Century

AnthroNotes Volume 28 No. 1 Spring 2007 WRITTEN IN BONE READING THE REMAINS OF THE 17TH CENTURY by Kari Bruwelheide and Douglas Owsley ˜ ˜ ˜ [Editor’s Note: The Smithsonian’s Department of Anthro- who came to America, many willingly and others under pology has had a long history of involvement in forensic duress, whose anonymous lives helped shaped the course anthropology by assisting law enforcement agencies in the of our country. retrieval, evaluation, and analysis of human remains for As we commemorate the 400th anniversary of the identification purposes. This article describes how settlement of Jamestown, it is clear that historians and ar- Smithsonian physical anthropologists are applying this same chaeologists have made much progress in piecing together forensic analysis to historic cases, in particular seventeenth the literary records and artifactual evidence that remain from century remains found in Maryland and Virginia, which the early colonial period. Over the past two decades, his- will be the focus of an upcoming exhibition, Written in Bone: torical archaeology especially has had tremendous success Forensic Files of the 17th Century, scheduled to open at the in charting the development of early colonial settlements Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in No- through careful excavations that have recovered a wealth vember 2008. This exhibition will cover the basics of hu- of 17th century artifacts, materials once discarded or lost, man anatomy and forensic investigation, extending these and until recently buried beneath the soil (Kelso 2006). Such techniques to the remains of colonists teetering on the edge discoveries are informing us about daily life, activities, trade of survival at Jamestown, Virginia, and to the wealthy and relations here and abroad, architectural and defensive strat- well-established individuals of St. -

Medieval Or Early Modern

Medieval or Early Modern Medieval or Early Modern The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton Medieval or Early Modern: The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Ronald Hutton and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7451-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7451-9 CONTENTS Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Ronald Hutton Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 10 From Medieval to Early Modern: The British Isles in Transition? Steven G. Ellis Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 29 The British Isles in Transition: A View from the Other Side Ronald Hutton Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 42 1492 Revisited Evan T. Jones Chapter Five ............................................................................................. -

The Slow Death of Slavery in Nineteenth Century Senegal and the Gold Coast

That Most Perfidious Institution: The slow death of slavery in nineteenth century Senegal and the Gold Coast Trevor Russell Getz Submitted for the degree of PhD University of London, School or Oriental and African Studies ProQuest Number: 10673252 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673252 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract That Most Perfidious Institution is a study of Africans - slaves and slave owners - and their central roles in both the expansion of slavery in the early nineteenth century and attempts to reform servile relationships in the late nineteenth century. The pivotal place of Africans can be seen in the interaction between indigenous slave-owning elites (aristocrats and urban Euro-African merchants), local European administrators, and slaves themselves. My approach to this problematic is both chronologically and geographically comparative. The central comparison between Senegal and the Gold Coast contrasts the varying impact of colonial policies, integration into the trans-Atlantic economy; and, more importantly, the continuity of indigenous institutions and the transformative agency of indigenous actors. -

The Transatlantic Slave Trade and the Creation of the English Weltanschauung, 1685-1710

The Transatlantic Slave Trade and the Creation of the English Weltanschauung, 1685-1710 James Buckwalter James Buckwalter, a member of Phi Alpha Theta, is a senior majoring in History with a Secondary Education Teaching Certificate from Tinley Park, Illinois. He wrote this paper for an independent study course with Dr. Key during the fall of 2008. At the turn of the-eighteenth century, the English public was confronted with numerous and conflicting interpretations of Africans, slavery, and the slave trade. On the one hand, there were texts that glorified the institution of slavery. Gabriel de Brémond’s The Happy Slave, which was translated and published in London in 1686, tells of a Roman, Count Alexander, who is captured off the coast of Tunis by “barbarians,” but is soon enlightened to the positive aspects of slavery, such as, being “lodged in a handsome apartment, where the Baffa’s Chyrurgions searched his Wounds: And…he soon found himself better.”58 On the other hand, Bartolomé de las Casas’ Popery truly display'd in its bloody colours (written in 1552, but was still being published in London in 1689), displays slavery in the most negative light. De las Casas chastises the Spaniards’ “bloody slaughter and destruction of men,” condemning how they “violently forced away Women and Children to make them slaves, and ill-treated them, consuming and wasting their food.”59 Moreover, Thomas Southerne’s adaptation of Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko in 1699 displays slavery in a contradictory light. Southerne condemns Oroonoko’s capture as a “tragedy,” but like Behn’s version, Oroonoko’s royalty complicates the matter, eventually causing the author to show sympathy for the enslaved African prince. -

The Southern Colonies in the 17Th and 18Th Centuries

AP U.S. History: Unit 2.1 Student Edition The Southern Colonies in the 17th and 18th Centuries I. Southern plantation colonies: general characteristics A. Dominated to a degree by a plantation economy: tobacco and rice B. Slavery in all colonies (even Georgia after 1750); mostly indentured servants until the late-17th century in Virginia and Maryland; increasingly black slavery thereafter C. Large land holdings owned by aristocrats; aristocratic atmosphere (except North Carolina and parts of Georgia in the 18th century). D. Sparsely populated: churches and schools were too expensive to build for very small towns. E. Religious toleration: the Church of England (Anglican Church) was the most prominent F. Expansionary attitudes resulted from the need for new land to compensate for the degradation of existing lands from soil-depleting tobacco farming; this expansion led to conflicts with Amerindians. II. The Chesapeake (Virginia and Maryland) A. Virginia (founded in 1607 by the Virginia Company) 1. Jamestown, 1607: 1st permanent British colony in New World a. Virginia Company: joint-stock company that received a charter from King James I in 1606 to establish settlements in North America. Main goals: Promise of gold, conversion of Amerindians to Christianity (like Spain had done), and new passage through North America to the East Indies (Northwest Passage). Consisted largely of well-to-do adventurers. b. Virginia Charter Overseas settlers were given same rights of Englishmen in England. Became a foundation for American liberties; similar rights would be extended to other North American colonies. 2. Jamestown was wracked by tragedy during its early years: famine, disease, and war with Amerindians a. -

Mn WORKING PAPERS in ECONOMIC HISTORY

rm London School of Economics & Political Science mn WORKING PAPERS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY 'PAWNS WILL LIVE WHEN SLAVES IS APT TO DYE': CREDIT, SLAVING AND PAWNSHIP AT OLD CALABAR IN THE ERA OF THE SLAVE TRADE Paul E. Lovejoy and David Richardson Number: 38/97 November 1997 Working Paper No. 38/97 (Pawns will live when slaves is apt to dye': Credit, Slaving and Pawnship at Old Calabar in the era of the Slave Trade Paul E. Lovejoy and David Richardson ~P.E. LovejoylDavid Richardson Department of Economic History London School of Economics November 1997 Paul E. Lovejoy and David Richardson, Clo Department of Economic History, London School of Economics, Houghton Street, London. WC2A 2AE. Telephone: +44 (0)1719557084 Fax: +44 (0)171 9557730 Additional copies of this working paper ar~ available at a cost of £2.50. Cheques should be made payable to 'Department of Economic History, LSE' and sent to the Economic History Department Secretary, LSE, Houghton Street, London.WC2A 2AE, U.K. Acknowledgement This paper was presented at a meeting of the Seminar on the Comparative Economic History of Africa, Asia and Latin America at LSE earlier in 1997. The Department of Economic History acknowledges the financial support from the Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines (STICERD), which made the seminar possible. Note on the authors Paul Lovejoy is Distinguished Research Professor at York University, Canada. He is the author of many essays, several books, and has edited several collections of papers: on African economic history and the history of slavery. His books include Transformations in Slavery: a history ofslavery in Africa (1983) and (with Jan Hogendorn), Slow Death for Slavery: the course ofabolition in Northern Nigeria, 1897-1936 (1993). -

(Re)Financing the Slave Trade with the Royal African Company in the Boom Markets of 17201

CENTRE FOR DYNAMIC MACROECONOMIC ANALYSIS WORKING PAPER SERIES CDMA11/14 (Re)financing the Slave Trade with the Royal African Company in the Boom Markets of 17201 Gary S. Shea2 University of St Andrews OCTOBER 2011 ABSTRACT In 1720, subscription finance and its attendant financial policies were highly successful for the Royal African Company. The values of subscription shares are easily understandable using standard elements of derivative security pricing theory. Sophisticated provision for protection of shareholder wealth made subscription finance successful; its parallels with modern innovated securities are demonstrated. A majority of Company shareholders participated in the re-financing, but could provide only a small portion of the new equity required. The re-financing attracted to the subscription an investment class that was strongly composed of parliamentary and aristocratic elements, but appeared to be only weakly attractive to persons who had already invested in the East India Company and was not attractive at all to Bank of England investors or to those persons who were investing in newly created marine insurance companies. Subsequent trade in subscription shares was more intense than was other share trading during the South Sea Bubble, but the trade was only lightly served by financial intermediaries. Professional financial intermediaries did not form densely connected networks of trade that were the hallmarks of Bank of England and East India Company share trading. The re-financing launched an only briefly successful revival of the Company’s slave trade. JEL Classification: N23, G13. Keywords: South Sea Company; South Sea Bubble; goldsmith bankers; subscription shares; call options; derivatives; installment receipts; innovated securities; networks.