Wattled Crane (Bugeranus Carunculatus)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Brochure

Fifty years ago our National Bird, the Blue Crane, was a common sight in South Africa's grasslands, today it is rare. The KZN Crane Foundation, was formed to understand why and find ways to reverse this trend. inside front cover The KZN Crane Foundation By the year 2000, the number of Blue Cranes in the grasslands of the Eastern Cape, KZN, the Free State, Gauteng, and Mpumalanga, had declined by 90%. Their breeding requirements are, however, flexible and they have been able to adapt to new habitats in the Karoo and the wheat-lands of the Southern Cape and the total national population appears, for now, although greatly reduced, to be stable. Wattled Cranes (our largest and most regal species), unlike Blue Cranes, are much more specific about their nesting requirements (needing wetlands) and have been unable to adapt to other habitats. Like the Blue Cranes their population plummeted during the Nineteen eighties and nineties and by the year 2000, only 80 breeding pairs remained, an almost unsustainable level. At the time, their extinction seemed inevitable. In light of this, in 1989 concerned conservationists, under the leadership of the then Natal Parks Board, formed the KZN Crane Foundation with the aim of understanding and reversing this decline. (Photo Thanks to Daniel Dolpire) Are Cranes Important? Cranes are ancient birds whose elegance and beauty have long captured man's imagination, with references to them in the bible and the mythologies of many cultures, as symbols of peace, fidelity, and longevity. South African legend has it that Shaka wore Blue Crane feathers in his head-dress and decreed that feathers of these magnificent birds may be worn only by kings. -

Conservation Measures for the Siberian Crane

CMS Technical Series Publication No. 1 Conservation Measures for the Siberian Crane Convention on Migratory Species Published by: UNEP/CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany Recommended citation: UNEP/CMS. ed.(1999). Conservation Measures for the Siberian Crane. CMS Technical Series Publication No.1, UNEP/CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany. Cover photograph: Siberian Crane (Grus leucogeranus) in snow. © Sietre / BIOS, Paris © UNEP/CMS, 1999 (copyright of individual contributions remains with the authors). Reproduction of this publication, except the cover photograph, for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorized without permission from the copyright holder, provided the source is cited and the copyright holder receives a copy of the reproduced material. Reproduction of the text for resale or other commercial purposes, or of the cover photograph, is prohibited without prior permission of the copyright holder. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP/CMS, nor are they an official record. The designation of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP/CMS concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, nor concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries. Copies of this publication are available from the UNEP/CMS Secretariat, United Nations Premises in Bonn, Martin-Luther-King-Str. 8, D-53175 -

Modelling Risk of Blue Crane (Anthropoides Paradiseus) Collision With

Modelling risk of Blue Crane (Anthropoides paradiseus) collision with power lines in the Overberg region By MapuIe Kotoane Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: Mr. A van Niekerk December 2004 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za AUTHOR'S DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date November 12, 2004 . 111 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT This study addresses the problem of Blue Crane (Anthropoides paradiseus) collisions with power lines in the Overberg region, home to approximately 50% of South Africa's national bird's global population. The low visibility of power lines against the landscape is considered to be the major cause of collisions. These claim at least 20 birds annually, which is a considerable loss to a vulnerable species. For this study, expert knowledge of the Blue Cranes' biology, general behaviour and use of its habitat were compiled. These were then translated into rules that were integrated into a Geographic Information System (GIS) to establish a predictive model, which attempts to identify and quantify risk power lines that Blue Cranes are most likely to collide with. The criteria that were considered included landscape proximity of power lines to water bodies arid congregation sites, land cover, power lines orientation in relation to predominant wind directions (North Westerly and South Easterly) and visibility of the power lines against the landscape. -

2018 Catalogue

2018 catalogue Birds | Reptiles | Trees | Geology | Mammals Popular science | General wildlife and more www.struiknatureclub.co.za BIRDS BIRDS A wide range of bird books, from field guides to collections of bird calls and bird Birds narratives. Covers the spectrum of bird ID, behaviour, how to find birds, attract 300 easY-to-SEE them and identify their calls. See also our series guides on pages 18–21. birds IN SOUTHERN AFRICA Introduces 300 of the SASOL BIRDS OF SOUTHERN TOP region’s easiest-to-see birds, AFRICA IV SELLER using a combination of Written by a team of highly respected artwork, photographs and authorities, namely Ian Sinclair, Phil Hockey, straightforward text. Warwick Tarboton and Peter Ryan, and 978 1 77007 623 5 978 1 77584 126 5 978 1 77584 172 2 illustrated by Norman Arlott and Peter Hayman. 978 1 77007 884 0 (PVC) ALSO AVAILABLE SASOL BIRDS OF SOUTHERN AFRICA IV LARGER EDITION 978 1 77584 099 2 978 1 77007 925 0 (Softcover) 978 1 77007 926 7 (Softcover) 978 1 77007 927 4 (PVC) 978 1 77007 928 1 (PVC) Comprehensively illustrated, and trusted by leading bird guides 978 1 43170 085 1 GUIDE to birds NEWMAN’s claSSIC ID GUIDES OF THE KRUGER GUIDE TO SEABIRDS OF SOUTHERN AFRICA national PARK Focusing exclusively on the 132 bird species that occur around the Attractive and handy field southern African coastline and adjacent Southern Ocean. A must-have guide listing more than for birders along the region’s extensive coastline. 500 species that have been recorded in the KNP. -

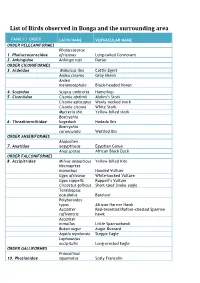

Birds Species in Bonga List

List of Birds observed in Bonga and the surrounding area FAMILY / ORDER LATIN NAME VERNACULAR NAME ORDER PELECANIFORMES Phalacrocorax 1. Phalacrocoracidae africanus Long-tailed Cormorant 2. Anhingidae Anhinga rufa Darter ORDER CICONIIFORMES 3. Ardeidae Bubulcus ibis Cattle Egret Ardea cinerea Grey Heron Ardea melanocephala Black-headed Heron 4. Scopidae Scopus umbretta Hamerkop 5. Ciconiidae Ciconia abdimii Abdim’s Stork Ciconia episcopus Wooly -necked stork Ciconia ciconia White Stork Mycteria ibis Yellow -billed stork Bostrychia 6. Threskiornithidae hagedash Hadada Ibis Bostrychia carunculata Wattled Ibis ORDER ANSERIFORMES Alopochen 7. Anatidae aegyptiacus Egyptian Goose Anas sparsa African Black Duck ORDER FALCONIFORMES 8. Accipitridae Milvus aegypticus Yellow -billed Kite Necrosyrtes monachus Hooded Vulture Gyps africanus White -backed Vulture Gyps ruppellii Ruppell’s Vulture Circaetus gallicus Short -toed Snake -eagle Terathopius ecaudatus Bateleur Polyboroides typus African Harrier Hawk Accipiter Red -breasted/Rufous -chested Sparrow rufiventris hawk Accipiter minullus Little Sparrowhawk Buteo augur Augur Buzzard Aquila nipalensis Steppe Eagle Lophoaetus occipitalis Long-crested Eagle ORDER GALLIFORMES Francolinus 10. Phasianidae squamatus Scaly Francolin FAMILY / ORDER LATIN NAME VERNACULAR NAME Francolinus castaneicollis Chestnut-napped Francolin ORDER GRUIFORMES Balearica 11. Gruidae pavonina Black Crowned Crane Bugeranus carunculatus Wattled crane Ruogetius 12. Rallidae rougetii Rouget’s Rail Podica 13. Heliornithidae senegalensis African Finfoot ORDER CHARADRIIFORMES 14. Scolopacidae Tringa ochropus Green Sandpiper Tringa hypolucos Common Sandpiper ORDER COLUMBIFORMES 15. Columbidae Columba guinea Speckled Pigeon Columba arquatrix African Olive Pigeon (Rameron Pigeon) Streptopelia lugens Dusky (Pink-breasted) Turtle Dove Streptopelia semitorquata Red-eyed Dove Turtur chalcospilos Emerald-spotted Wood Dove Turtur tympanistria Tambourine Dove ORDER CUCULIFORMES 17. Musophagidae Tauraco leucotis White -cheeked Turaco Centropus 18. -

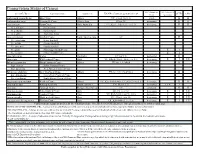

Conservation Status of Cranes

Conservation Status of Cranes IUCN Population ESA Endangered Scientific Name Common name Continent IUCN Red List Category & Criteria* CITES CMS Trend Species Act Anthropoides paradiseus Blue Crane Africa VU A2acde (ver 3.1) stable II II Anthropoides virgo Demoiselle Crane Africa, Asia LC(ver 3.1) increasing II II Grus antigone Sarus Crane Asia, Australia VU A2cde+3cde+4cde (ver 3.1) decreasing II II G. a. antigone Indian Sarus G. a. sharpii Eastern Sarus G. a. gillae Australian Sarus Grus canadensis Sandhill Crane North America, Asia LC II G. c. canadensis Lesser Sandhill G. c. tabida Greater Sandhill G. c. pratensis Florida Sandhill G. c. pulla Mississippi Sandhill Crane E I G. c. nesiotes Cuban Sandhill Crane E I Grus rubicunda Brolga Australia LC (ver 3.1) decreasing II Grus vipio White-naped Crane Asia VU A2bcde+3bcde+4bcde (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Balearica pavonina Black Crowned Crane Africa VU (ver 3.1) A4bcd decreasing II B. p. ceciliae Sudan Crowned Crane B. p. pavonina West African Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum Grey Crowned Crane Africa EN (ver. 3.1) A2acd+4acd decreasing II B. r. gibbericeps East African Crowned Crane B. r. regulorum South African Crowned Crane Bugeranus carunculatus Wattled Crane Africa VU A2acde+3cde+4acde; C1+2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing II II Grus americana Whooping Crane North America EN, D (ver 3.1) increasing E, EX I Grus grus Eurasian Crane Europe/Asia/Africa LC unknown II II Grus japonensis Red-crowned Crane Asia EN, C1 (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Grus monacha Hooded Crane Asia VU B2ab(I,ii,iii,iv,v); C1+2a(ii) decreasing E I I,II Grus nigricollis Black-necked Crane Asia VU C2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Leucogeranus leucogeranus Siberian Crane Asia CR A3bcd+4bcd (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Conservation status of species in the wild based on: The 2015 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, www.redlist.org CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) - A taxon is Critically Endangered when it is facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future. -

Bumper Crop of Chicks at Crane Foundation by International Crane Foundation Baraboo, Wisconsin

Bumper Crop of Chicks at Crane Foundation by International Crane Foundation Baraboo, Wisconsin This summer in Wisconsin, the corn youngsters about a foot high, to the larger one. As the gangly chicks run, may be late from excessive rain but Wattled Crane named Maozeka who, they extend their wings, which flop as chicks are sprouting early at the Inter at ten weeks of age, stands about if made of rubber. national Crane Foundation ClCF). This three feet tall. The chicks grow up to According to ICF intern Debra year's bumper crop of chicks got off to an inch a day, because in the wild Bourne, the tiny bullies can be u eful an early start when the endangered many have to migrate more than a when they chase the larger chicks. Wattled Cranes from Africa laid during thousand miles by the end of summer. Since they can't catch and harm the a snow storm in FebrualY. Now there Getting plenty of exercise is vital for larger chicks, all get plenty of exer are 24 chicks at the facility, with proper development of their spindly cise. But tlle ICF staff has to be careful another expected. Up to 17 of the legs. not to put a bully in the chick yard chicks are on public display in the Besides monitoring the health of the along with smaller chicks they might "chick yard," where the chicks are chicks and feeding them, the volun pick on. If the excitement get outs of attended by volunteer "chick par teer chick parents have to keep the hand, the offender is placed in the ents." bullies from hurting less aggressive "penalty box," a small pen within the According to Assistant Curator of chicks. -

Near-Ultraviolet Light Reduced Sandhill Crane Collisions with a Power Line by 98% James F

AmericanOrnithology.org Volume XX, 2019, pp. 1–10 DOI: 10.1093/condor/duz008 RESEARCH ARTICLE Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/condor/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/condor/duz008/5476728 by University of Nebraska Kearney user on 09 May 2019 Near-ultraviolet light reduced Sandhill Crane collisions with a power line by 98% James F. Dwyer,*, Arun K. Pandey, Laura A. McHale, and Richard E. Harness EDM International, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA *Corresponding author: [email protected] Submission Date: 6 September, 2018; Editorial Acceptance Date: 25 February, 2019; Published May 6, 2019 ABSTRACT Midflight collisions with power lines impact 12 of the world’s 15 crane species, including 1 critically endangered spe- cies, 3 endangered species, and 5 vulnerable species. Power lines can be fitted with line markers to increase the visi- bility of wires to reduce collisions, but collisions can persist on marked power lines. For example, hundreds of Sandhill Cranes (Antigone canadensis) die annually in collisions with marked power lines at the Iain Nicolson Audubon Center at Rowe Sanctuary (Rowe), a major migratory stopover location near Gibbon, Nebraska. Mitigation success has been limited because most collisions occur nocturnally when line markers are least visible, even though roughly half the line markers present include glow-in-the-dark stickers. To evaluate an alternative mitigation strategy at Rowe, we used a randomized design to test collision mitigation effects of a pole-mounted near-ultraviolet light (UV-A; 380–395 nm) Avian Collision Avoidance System (ACAS) to illuminate a 258-m power line span crossing the Central Platte River. We observed 48 Sandhill Crane collisions and 217 dangerous flights of Sandhill Crane flocks during 19 nights when the ACAS was off, but just 1 collision and 39 dangerous flights during 19 nights when the ACAS was on. -

Wattled Crane . Bugeranus Carunculaius

THE USE OF A GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEM TO INVESTIGATE THE EFFECT OF LAND-USE CHANGE ON WATTLED CRANE Bugeranus caruncula/us BREEDING PRODUCTIVITY IN KWAZULU-NATAL, SOUTH AFRICA. by BRENTNULESCOVERDALE Submitted as the dissertation component in partial fulfilment ofthe requirements for the degree Master ofEnvironment and Development in the Centre for Environment, Agriculture and Development, University ofKwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg. JULY 2006 "The fate of birds, mammals, frogs, fish and all the rest of biodiversity depends not so much on what happens in parks but what happens where we live, work, and obtain the wherewithal for our daily lives. To give biodiversity and wildlands breathing space, we must reduce the size of our own imprint on the planet." John Tuxill (1998: 72) PREFACE The work described in this dissertation was carried out in the Centre for Environment, Agriculture and Development, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, from September 2003 to November 2005, under the supervision of ProfT. Hill (Discipline ofGeography) and K.!. McCann (Endangered Wildlife Trust). The format adopted for this dissertation departs from the conventional style, in that it is presented as two separate components, Component A, comprising an Introduction, Literature review and description of Methods, whilst Component B is submitted in the form of an academic paper, to be published in the Journal of Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. This study represents original work by the author and has not otherwise been submitted in any form for any degree or diploma to any other University. Where use has been made ofthe work ofothers this is duly acknowledged. Portions ofthis work include intellectual property of the CSIR/Agricultural research Council and are used herein by permission. -

SOUTH AFRICA: LAND of the ZULU 26Th October – 5Th November 2015

Tropical Birding Trip Report South Africa: October/November 2015 A Tropical Birding CUSTOM tour SOUTH AFRICA: LAND OF THE ZULU th th 26 October – 5 November 2015 Drakensberg Siskin is a small, attractive, saffron-dusted endemic that is quite common on our day trip up the Sani Pass Tour Leader: Lisle Gwynn All photos in this report were taken by Lisle Gwynn. Species pictured are highlighted RED. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-0514 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report South Africa: October/November 2015 INTRODUCTION The beauty of Tropical Birding custom tours is that people with limited time but who still want to experience somewhere as mind-blowing and birdy as South Africa can explore the parts of the country that interest them most, in a short time frame. South Africa is, without doubt, one of the most diverse countries on the planet. Nowhere else can you go from seeing Wandering Albatross and penguins to seeing Leopards and Elephants in a matter of hours, and with countless world-class national parks and reserves the options were endless when it came to planning an itinerary. Winding its way through the lush, leafy, dry, dusty, wet and swampy oxymoronic province of KwaZulu-Natal (herein known as KZN), this short tour followed much the same route as the extension of our South Africa set departure tour, albeit in reverse, with an additional focus on seeing birds at the very edge of their range in semi-Karoo and dry semi-Kalahari habitats to add maximum diversity. KwaZulu-Natal is an oft-underrated birding route within South Africa, featuring a wide range of habitats and an astonishing diversity of birds. -

The Cranes Compiled by Curt D

Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan The Cranes Compiled by Curt D. Meine and George W. Archibald IUCN/SSC Crane Specialist Group IUCN The World Conservation Union IUCN/Species Survival Commission Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Fund and The Cranes: Status Survey & Conservation Action Plan The IUCN/Species Survival Commission Conservation Communications Fund was established in 1992 to assist SSC in its efforts to communicate important species conservation information to natural resource managers, deci- sion-makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC's Action Plans, occasional papers, news magazine (Species), Membership Directory and other publi- cations are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation; to date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to Specialist Groups. As a result, the Action Plan Programme has progressed at an accelerated level and the network has grown and matured significantly. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and sup- port for species conservation worldwide. The Chicago Zoological Society (CZS) provides significant in-kind and cash support to the SSC, including grants for special projects, editorial and design services, staff secondments and related support services. The President of CZS and Director of Brookfield Zoo, George B. Rabb, serves as the volunteer Chair of the SSC. The mis- sion of CZS is to help people develop a sustainable and harmonious relationship with nature. The Zoo carries out its mis- sion by informing and inspiring 2,000,000 annual visitors, serving as a refuge for species threatened with extinction, developing scientific approaches to manage species successfully in zoos and the wild, and working with other zoos, agencies, and protected areas around the world to conserve habitats and wildlife. -

Phylogeny of Cranes (Gruiformes: Gruidae) Based on Cytochrome-B Dna Sequences

The Auk 111(2):351-365, 1994 PHYLOGENY OF CRANES (GRUIFORMES: GRUIDAE) BASED ON CYTOCHROME-B DNA SEQUENCES CAREY KRAJEWSKIAND JAMESW. FETZNER,JR. • Departmentof Zoology,Southern Illinois University, Carbondale,Illinois 62901-6501, USA ABS?RACr.--DNAsequences spanning 1,042 nucleotide basesof the mitochondrial cyto- chrome-b gene are reported for all 15 speciesand selected subspeciesof cranes and an outgroup, the Limpkin (Aramusguarauna). Levels of sequencedivergence coincide approxi- mately with current taxonomicranks at the subspecies,species, and subfamilial level, but not at the generic level within Gruinae. In particular, the two putative speciesof Balearica (B. pavoninaand B. regulorum)are as distinct as most pairs of gruine species.Phylogenetic analysisof the sequencesproduced results that are strikingly congruentwith previousDNA- DNA hybridization and behavior studies. Among gruine cranes, five major lineages are identified. Two of thesecomprise single species(Grus leucogeranus, G. canadensis), while the others are speciesgroups: Anthropoides and Bugeranus;G. antigone,G. rubicunda,and G. vipio; and G. grus,G. monachus,G. nigricollis,G. americana,and G. japonensis.Within the latter group, G. monachusand G. nigricollisare sisterspecies, and G. japonensisappears to be the sistergroup to the other four species.The data provide no resolutionof branchingorder for major groups, but suggesta rapid evolutionary diversification of these lineages. Received19 March 1993, accepted19 August1993. THE 15 EXTANTSPECIES of cranescomprise the calls.These