Blue Crane (Anthropoides Paradises)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modelling Risk of Blue Crane (Anthropoides Paradiseus) Collision With

Modelling risk of Blue Crane (Anthropoides paradiseus) collision with power lines in the Overberg region By MapuIe Kotoane Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: Mr. A van Niekerk December 2004 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za AUTHOR'S DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date November 12, 2004 . 111 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT This study addresses the problem of Blue Crane (Anthropoides paradiseus) collisions with power lines in the Overberg region, home to approximately 50% of South Africa's national bird's global population. The low visibility of power lines against the landscape is considered to be the major cause of collisions. These claim at least 20 birds annually, which is a considerable loss to a vulnerable species. For this study, expert knowledge of the Blue Cranes' biology, general behaviour and use of its habitat were compiled. These were then translated into rules that were integrated into a Geographic Information System (GIS) to establish a predictive model, which attempts to identify and quantify risk power lines that Blue Cranes are most likely to collide with. The criteria that were considered included landscape proximity of power lines to water bodies arid congregation sites, land cover, power lines orientation in relation to predominant wind directions (North Westerly and South Easterly) and visibility of the power lines against the landscape. -

2018 Catalogue

2018 catalogue Birds | Reptiles | Trees | Geology | Mammals Popular science | General wildlife and more www.struiknatureclub.co.za BIRDS BIRDS A wide range of bird books, from field guides to collections of bird calls and bird Birds narratives. Covers the spectrum of bird ID, behaviour, how to find birds, attract 300 easY-to-SEE them and identify their calls. See also our series guides on pages 18–21. birds IN SOUTHERN AFRICA Introduces 300 of the SASOL BIRDS OF SOUTHERN TOP region’s easiest-to-see birds, AFRICA IV SELLER using a combination of Written by a team of highly respected artwork, photographs and authorities, namely Ian Sinclair, Phil Hockey, straightforward text. Warwick Tarboton and Peter Ryan, and 978 1 77007 623 5 978 1 77584 126 5 978 1 77584 172 2 illustrated by Norman Arlott and Peter Hayman. 978 1 77007 884 0 (PVC) ALSO AVAILABLE SASOL BIRDS OF SOUTHERN AFRICA IV LARGER EDITION 978 1 77584 099 2 978 1 77007 925 0 (Softcover) 978 1 77007 926 7 (Softcover) 978 1 77007 927 4 (PVC) 978 1 77007 928 1 (PVC) Comprehensively illustrated, and trusted by leading bird guides 978 1 43170 085 1 GUIDE to birds NEWMAN’s claSSIC ID GUIDES OF THE KRUGER GUIDE TO SEABIRDS OF SOUTHERN AFRICA national PARK Focusing exclusively on the 132 bird species that occur around the Attractive and handy field southern African coastline and adjacent Southern Ocean. A must-have guide listing more than for birders along the region’s extensive coastline. 500 species that have been recorded in the KNP. -

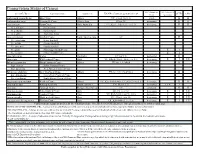

Conservation Status of Cranes

Conservation Status of Cranes IUCN Population ESA Endangered Scientific Name Common name Continent IUCN Red List Category & Criteria* CITES CMS Trend Species Act Anthropoides paradiseus Blue Crane Africa VU A2acde (ver 3.1) stable II II Anthropoides virgo Demoiselle Crane Africa, Asia LC(ver 3.1) increasing II II Grus antigone Sarus Crane Asia, Australia VU A2cde+3cde+4cde (ver 3.1) decreasing II II G. a. antigone Indian Sarus G. a. sharpii Eastern Sarus G. a. gillae Australian Sarus Grus canadensis Sandhill Crane North America, Asia LC II G. c. canadensis Lesser Sandhill G. c. tabida Greater Sandhill G. c. pratensis Florida Sandhill G. c. pulla Mississippi Sandhill Crane E I G. c. nesiotes Cuban Sandhill Crane E I Grus rubicunda Brolga Australia LC (ver 3.1) decreasing II Grus vipio White-naped Crane Asia VU A2bcde+3bcde+4bcde (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Balearica pavonina Black Crowned Crane Africa VU (ver 3.1) A4bcd decreasing II B. p. ceciliae Sudan Crowned Crane B. p. pavonina West African Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum Grey Crowned Crane Africa EN (ver. 3.1) A2acd+4acd decreasing II B. r. gibbericeps East African Crowned Crane B. r. regulorum South African Crowned Crane Bugeranus carunculatus Wattled Crane Africa VU A2acde+3cde+4acde; C1+2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing II II Grus americana Whooping Crane North America EN, D (ver 3.1) increasing E, EX I Grus grus Eurasian Crane Europe/Asia/Africa LC unknown II II Grus japonensis Red-crowned Crane Asia EN, C1 (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Grus monacha Hooded Crane Asia VU B2ab(I,ii,iii,iv,v); C1+2a(ii) decreasing E I I,II Grus nigricollis Black-necked Crane Asia VU C2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Leucogeranus leucogeranus Siberian Crane Asia CR A3bcd+4bcd (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Conservation status of species in the wild based on: The 2015 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, www.redlist.org CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) - A taxon is Critically Endangered when it is facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future. -

Wattled Crane (Bugeranus Carunculatus)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences January 1983 Cranes of the World: Wattled Crane (Bugeranus carunculatus) Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscicranes Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Cranes of the World: Wattled Crane (Bugeranus carunculatus)" (1983). Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard. 29. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscicranes/29 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Wattled Crane Bugeranus carunculatus (Gmelin) 1789 Other Vernacular Names. Great African wattled crane; male is darker red than that of the female. In both sexes Grue caroncule (French); Glockenkranich, Klun- this bare area is covered by small, rounded excrescences. kerkranich (German); Hooka Zuru (Japanese); The feathered portion of the head is dark slaty gray Asbrikanskiy Sorodavachaty (Russian); Mothla- above the eyes and on the crown, but is otherwise white, thomo (Sotho, Sesuto); Grulla zarzo (Spanish); including the wattles, which are almost fully feathered Makalanga (Zambian). and hang down from the region of the upper throat. Range. Resident in eastern and southern Africa, from The mantle, breast, primaries, secondaries, tail coverts, Ethiopia in the north southward discontinuously and tail are black, and the remainder of the back and through southern Tanzania (apparently absent wings are ashy gray. -

Near-Ultraviolet Light Reduced Sandhill Crane Collisions with a Power Line by 98% James F

AmericanOrnithology.org Volume XX, 2019, pp. 1–10 DOI: 10.1093/condor/duz008 RESEARCH ARTICLE Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/condor/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/condor/duz008/5476728 by University of Nebraska Kearney user on 09 May 2019 Near-ultraviolet light reduced Sandhill Crane collisions with a power line by 98% James F. Dwyer,*, Arun K. Pandey, Laura A. McHale, and Richard E. Harness EDM International, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA *Corresponding author: [email protected] Submission Date: 6 September, 2018; Editorial Acceptance Date: 25 February, 2019; Published May 6, 2019 ABSTRACT Midflight collisions with power lines impact 12 of the world’s 15 crane species, including 1 critically endangered spe- cies, 3 endangered species, and 5 vulnerable species. Power lines can be fitted with line markers to increase the visi- bility of wires to reduce collisions, but collisions can persist on marked power lines. For example, hundreds of Sandhill Cranes (Antigone canadensis) die annually in collisions with marked power lines at the Iain Nicolson Audubon Center at Rowe Sanctuary (Rowe), a major migratory stopover location near Gibbon, Nebraska. Mitigation success has been limited because most collisions occur nocturnally when line markers are least visible, even though roughly half the line markers present include glow-in-the-dark stickers. To evaluate an alternative mitigation strategy at Rowe, we used a randomized design to test collision mitigation effects of a pole-mounted near-ultraviolet light (UV-A; 380–395 nm) Avian Collision Avoidance System (ACAS) to illuminate a 258-m power line span crossing the Central Platte River. We observed 48 Sandhill Crane collisions and 217 dangerous flights of Sandhill Crane flocks during 19 nights when the ACAS was off, but just 1 collision and 39 dangerous flights during 19 nights when the ACAS was on. -

The Cranes Compiled by Curt D

Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan The Cranes Compiled by Curt D. Meine and George W. Archibald IUCN/SSC Crane Specialist Group IUCN The World Conservation Union IUCN/Species Survival Commission Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Fund and The Cranes: Status Survey & Conservation Action Plan The IUCN/Species Survival Commission Conservation Communications Fund was established in 1992 to assist SSC in its efforts to communicate important species conservation information to natural resource managers, deci- sion-makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC's Action Plans, occasional papers, news magazine (Species), Membership Directory and other publi- cations are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation; to date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to Specialist Groups. As a result, the Action Plan Programme has progressed at an accelerated level and the network has grown and matured significantly. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and sup- port for species conservation worldwide. The Chicago Zoological Society (CZS) provides significant in-kind and cash support to the SSC, including grants for special projects, editorial and design services, staff secondments and related support services. The President of CZS and Director of Brookfield Zoo, George B. Rabb, serves as the volunteer Chair of the SSC. The mis- sion of CZS is to help people develop a sustainable and harmonious relationship with nature. The Zoo carries out its mis- sion by informing and inspiring 2,000,000 annual visitors, serving as a refuge for species threatened with extinction, developing scientific approaches to manage species successfully in zoos and the wild, and working with other zoos, agencies, and protected areas around the world to conserve habitats and wildlife. -

Crane Husbandry Manual 1999

Cra n e s : Their Biology, Husband ry, and Conservati on E d i to r s David H. Ell i s George F. Gee Cl a i r e M. Mir a n d e Technical Edito r Catherine H. Ell i s Copy Edito r Lorie A. Sha u l l i v IS B N 0- 8 8 8 3 9 - 3 8 7 - 3 National Biological Se rv i c e / International Crane Foundation Limited Edi t i o n Catal oging in Publication Data Ellis, David, H., 1945- Cra n e s Includes bibliographical ref e r ences and index. ISBN 0-88839-385-3 1. Cranes (Bir ds) I. Tit l e . QL696.G84E44 199 6 59 8 . 3 ’1 C9 5 9 1 1 0 4 0 - 2 Printed in the United States of America, 199 6 Published by the Dep a r tment of the Int e r i o r , National Biological Se rv i c e , Washington, DC, and the International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, WI . Printed in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Se rv i c e . Table of Contents Authors and Ad d re s s e s . vi i Fo rewo rd. ix Pre fac e . xi 1 . Crane Bi o lo g y. George W. Archibald, James C. Lewi s 2 . General Hu s b a n d ry . Scott R. Swengel, James W. Carpenter 3 . Egg and Semen Pro d u c t i o n . Cl a i r e M. Mirande, George F. -

Cranes of the World: Index

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences January 1983 Cranes of the World: Index Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscicranes Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Cranes of the World: Index" (1983). Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscicranes/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INDEX This index is limited to the English vernacular and Latin names of crane species and subspecies, including fossil terms. Complete indexing is limited to entries for the English vernacular names of species as used in this book. The principal account of each species or genus is indicated by italics. americana, Grus, 27, 185-195, 239 59, 69, 70, 98-100, 102, 136, 156, 168, pratensis, Grus canadensis, 33, 17 1, 172, Anthropoides, 10,27,29,85,87-102,239, 205, 209-210, 212-213, 214, 215, 220, 239 24 1 221, 224, 227-237, 242 princeps, Paleogrus, 9 antigone, Grus, 27,151-158, 239 excelsus, Paleogrus, 9 problematica, Probalearica, 9 argentea, Grus, 141, 239 geiseltalensis, Paleogrus, 9 pul la, '~ruscanadensis, 171, 172, 239 Asiatic white crane. See Siberian crane. germanicus, Pliogrus, 9 punmunjomii, Grus japonensis, 197 Australian crane, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 37, gibbericeps, Balearica pavonina, 27, 77, red-crowned crane. -

Fairest Cape to Kruger 11Th – 27Th September, 2015

Fairest Cape to Kruger 11th – 27th September, 2015 Barrier of Spears extension 27th September – 3rd October, 2015 Set Departure tour Tour leader: Charley Hesse Report by Charley Hesse. Photos by Charley Hesse & Andrew Spencer With stiff competition, Buff-spotted Flufftail was voted bird of the trip (Andrew Spencer) There many different ways to birdwatch in South Africa, and with a small group of serious birdwatchers, we had a fast pace tour and accumulated a very large number of species. With a trip list of 494 species of birds, 67 species of mammals, plus many reptiles, amphibians and butterflies, it was one of our most successful tours to date. It was especially impressive considering that this didn’t even include a pelagic (which was sadly cancelled due to weather conditions). In addition to the huge species haul, our list included most of the available endemics (including both rockjumpers and sugarbirds) plus many other seldom seen birds. As well as the obvious star birds like African Penguin and Blue Crane, we did particularly well with certain groups, with 9 species of bustard, 14 species of larks (including the very rare Rudd’s), 32 species of hawks and eagles (including Crowned Hawk-Eagle & Fasciated Snake-Eagle) and 9 species of owls (including African Grass-Owl, Cape Eagle-Owl and the Holy Grail of African birding, Pel’s Fishing Owl). Mammals feature heavily on this tour and highlights from our list included Cheetah, White & Black Rhinos, Porcupine, Meercat & Southern Rights Whales. Of course the world class reserves, stunning scenery, high-quality lodging and food plus very friendly people didn’t go unnoticed either. -

Ancient DNA of New Zealand's Extinct Avifauna

I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide, and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University’s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. ………………………….. ………………………….. Alexander Boast Date “… a symphony of ‘the most tunable silver sound imaginable’. Aotearoa’s multitudes of birds performed that symphony each dawn for over 60 million years. It was a glorious riot of sound with its own special meaning, for it was a confirmation of the health of a wondrous and unique ecosystem. To my great regret, I arrived in New Zealand in the late twentieth century only to find most of the orchestra seats empty. -

Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences January 1983 Cranes of the World: References Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscicranes Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Cranes of the World: References" (1983). Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard. 24. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscicranes/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. REFERENCES The following list of more than 400 references is by no Ali, S., and Ripley, S. D. 1969. Handbook of the birds of India means a complete bibliography of cranes, but does include a and Pakistan. Vol. 2. Bombay: Oxford University Press. few titles that for various reasons were not specifically cited in Allen, R. P. 1952. The whooping crane. Research Report No. the text. Walkinshaw's (1973) monograph contains a large 2, National Audubon Society, New York. number of citations not found in the present list, and he -1956. A report on the whooping crane's northern additionally has recently (1981~)updated and supplemented breeding grounds. National Audubon Society, Supple- his earlier bibliography. All told, his two citation lists include ment to Research Report No. 2, 1-60. nearly 2,500 citations. Nearly 40 percent of the 1973 list deals Andreev, B. -

BLUE CRANE | Grus Paradisea (Anthropoides Paradiseus)

BLUE CRANE | Grus paradisea (Anthropoides paradiseus) RE Simmons | Reviewed by P Cunningham; H Kolberg; K McCann; HA Scott; D Young © Peter Ryan © Peter Conservation Status: Critically Endangered Southern African Range: North-central Namibia, southern Botswana, South Africa In Namibia, a tiny subpopulation is found only within 2 Area of Occupancy: 24,000 km the eastern parts of Etosha National Park and in the grasslands centred on the Omadhiya lakes, about 70 km Population Estimate: 35 birds (up to 12 pairs) north of the park (Allan 1997i, Simmons et al. 2006a). Population Trend: Apparently in decline The cranes are distributed mainly in the wetter parts of this rather arid region. Within the park, the cranes use Habitat: Wet grasslands and pans the area from Twee Palms and Fischer’s Pan westwards along the main pan to Salvadora/Sueda in the Halali Threats: Fragmented and genetically isolated population, human area at present, with only one recent sighting further encroachment, long-term westwards (at Newbrownii in November 2009). In changes in water availability the northern parts of the park they occur from Ekuma River in the west to Andoni in the east. The singlemost important site where birds assemble to roost is the Andoni gravel pit, when it holds water, where up to 35 DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE birds may be recorded. There are a few more widely The Blue Crane is endemic to southern Africa, with the scattered historical records, including one of at least smallest range of all of the world’s cranes (del Hoyo et one crane at Stampriet in July 1960 (Brown 1992b, W al.