A Level Film Studies Teacher Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Silent Films of Alfred Hitchcock

The Hitchcock 9 Silent Films of Alfred Hitchcock Justin Mckinney Presented at the National Gallery of Art The Lodger (British Film Institute) and the American Film Institute Silver Theatre Alfred Hitchcock’s work in the British film industry during the silent film era has generally been overshadowed by his numerous Hollywood triumphs including Psycho (1960), Vertigo (1958), and Rebecca (1940). Part of the reason for the critical and public neglect of Hitchcock’s earliest works has been the generally poor quality of the surviving materials for these early films, ranging from Hitchcock’s directorial debut, The Pleasure Garden (1925), to his final silent film, Blackmail (1929). Due in part to the passage of over eighty years, and to the deterioration and frequent copying and duplication of prints, much of the surviving footage for these films has become damaged and offers only a dismal representation of what 1920s filmgoers would have experienced. In 2010, the British Film Institute (BFI) and the National Film Archive launched a unique restoration campaign called “Rescue the Hitchcock 9” that aimed to preserve and restore Hitchcock’s nine surviving silent films — The Pleasure Garden (1925), The Lodger (1926), Downhill (1927), Easy Virtue (1927), The Ring (1927), Champagne (1928), The Farmer’s Wife (1928), The Manxman (1929), and Blackmail (1929) — to their former glory (sadly The Mountain Eagle of 1926 remains lost). The BFI called on the general public to donate money to fund the restoration project, which, at a projected cost of £2 million, would be the largest restoration project ever conducted by the organization. Thanks to public support and a $275,000 dona- tion from Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation in conjunction with The Hollywood Foreign Press Association, the project was completed in 2012 to coincide with the London Olympics and Cultural Olympiad. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin's Influence on American

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin’s Influence on American Animation By Nancy Beiman SLIDE 1: Joe Grant trading card of Chaplin and Mickey Mouse Charles Chaplin became an international star concurrently with the birth and development of the animated cartoon. His influence on the animation medium was immense and continues to this day. I will discuss how American character animators, past and present, have been inspired by Chaplin’s work. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND (SLIDE 2) Jeffrey Vance described Chaplin as “the pioneer subject of today’s modern multimedia marketing and merchandising tactics”, 1 “(SLIDE 3). Charlie Chaplin” comic strips began in 1915 and it was a short step from comic strips to animation. (SLIDE 4) One of two animated Chaplin series was produced by Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan Studios in 1918-19. 2 Immediately after completing the Chaplin cartoons, (SLIDE 5) Otto Messmer created Felix the Cat who was, by 1925, the most popular animated character in America. Messmer, by his own admission, based Felix’s timing and distinctive pantomime acting on Chaplin’s. 3 But no other animators of the time followed Messmer’s lead. (SLIDE 6) Animator Shamus Culhane wrote that “Right through the transition from silent films to sound cartoons none of the producers of animation paid the slightest attention to… improvements in the quality of live action comedy. Trapped by the belief that animated cartoons should be a kind of moving comic strip, all the producers, (including Walt Disney) continued to turn out films that consisted of a loose story line that supported a group of slapstick gags which were often only vaguely related to the plot….The most astonishing thing is that Walt Disney took so long to decide to break the narrow confines of slapstick, because for several decades Chaplin, Lloyd and Keaton had demonstrated the superiority of good pantomime.” 4 1 Jeffrey Vance, CHAPLIN: GENIUS OF THE CINEMA, p. -

Drawn to Sound

Introduction ix About the Authors Rebecca Coyle teaches in the Media Program at Southern Cross University, Australia, and has edited two anthologies on Australian cinema soundtracks, Screen Scores (1998) and Reel Tracks (2005). She is currently researching film music production within an Australian Research Council funded project, is Research Director for the School of Arts and Social Sciences, and has recently edited a special issue of Animation Journal (published 2009). Jon Fitzgerald teaches in the contemporary music programme at Southern Cross University, Australia. He has previously written on a variety of musical and screen sound topics and he is the author of Popular Music Theory and Musicianship (1999/2003). He is also an experienced performer and composer. Daniel Goldmark is Associate Professor of music at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. He is the series editor of the Oxford Music/Media Series, and is the author and/or editor of several books on animation, film, and music, including Tunes for ’Toons: Music and the Hollywood Cartoon (2005). Janet K. HalfJanet Halfyaryaryarddd is Director of Undergraduate Studies at Birmingham City University Conservatoire. Her publications include Danny Elfman’s Batman: A Film Score Guide (2004), an edited volume on Luciano Berio’s Sequenzas (2007), and a wide range of essays on music in film and cult televison. Philip Haywarddd is Director of Research Training at Southern Cross University, Aus- tralia and an adjunct professor in the Department of Media, Music and Cultural Studies at Macquarie University, Sydney. His previous screen sound books include Off the Planet: Music, Sound and Science Fiction Cinema (2005) and Terror Tracks: Music, Sound and Horror Cinema (2009). -

Film Culture in Transition

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art ERIKA BALSOM Amsterdam University Press Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Erika Balsom This book is published in print and online through the online OAPEN library (www.oapen.org) OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative in- itiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic research by aggregating peer reviewed Open Access publications from across Europe. Sections of chapter one have previously appeared as a part of “Screening Rooms: The Movie Theatre in/and the Gallery,” in Public: Art/Culture/Ideas (), -. Sections of chapter two have previously appeared as “A Cinema in the Gallery, A Cinema in Ruins,” Screen : (December ), -. Cover illustration (front): Pierre Bismuth, Following the Right Hand of Louise Brooks in Beauty Contest, . Marker pen on Plexiglas with c-print, x inches. Courtesy of the artist and Team Gallery, New York. Cover illustration (back): Simon Starling, Wilhelm Noack oHG, . Installation view at neugerriemschneider, Berlin, . Photo: Jens Ziehe, courtesy of the artist, neugerriemschneider, Berlin, and Casey Kaplan, New York. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: JAPES, Amsterdam isbn e-isbn (pdf) e-isbn (ePub) nur / © E. Balsom / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Silent Film Music and the Theatre Organ Thomas J. Mathiesen

Silent Film Music and the Theatre Organ Thomas J. Mathiesen Introduction Until the 1980s, the community of musical scholars in general regarded film music-and especially music for the silent films-as insignificant and uninteresting. Film music, it seemed, was utili tarian, commercial, trite, and manipulative. Moreover, because it was film music rather than film music, it could not claim the musical integrity required of artworks worthy of study. If film music in general was denigrated, the theatre organ was regarded in serious musical circles as a particular aberration, not only because of the type of music it was intended to play but also because it represented the exact opposite of the characteristics espoused by the Orgelbewegung of the twentieth century. To make matters worse, many of the grand old motion picture theatres were torn down in the fifties and sixties, their music libraries and theatre organs sold off piecemeal or destroyed. With a few obvious exceptions (such as the installation at Radio City Music Hall in New (c) 1991 Indiana Theory Review 82 Indiana Theory Review Vol. 11 York Cityl), it became increasingly difficult to hear a theatre organ in anything like its original acoustic setting. The theatre organ might have disappeared altogether under the depredations of time and changing taste had it not been for groups of amateurs that restored and maintained some of the instruments in theatres or purchased and installed them in other locations. The American Association of Theatre Organ Enthusiasts (now American Theatre Organ Society [ATOS]) was established on 8 February 1955,2 and by 1962, there were thirteen chapters spread across the country. -

Monumental Melodrama: Mikhail Kalatozov’S Retrospective Return to 1920S Agitprop Cinema in I Am Cuba Tim Harte Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Russian Faculty Research and Scholarship Russian 2013 Monumental Melodrama: Mikhail Kalatozov’s Retrospective Return to 1920s Agitprop Cinema in I Am Cuba Tim Harte Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/russian_pubs Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Custom Citation Harte, Tim. "Monumental Melodrama: Mikhail Kalatozov’s Retrospective Return to 1920s Agitprop Cinema in I Am Cuba." Anuari de filologia. Llengües i literatures modernes 3 (2013) 1-12. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/russian_pubs/2 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tim Harte Bryn Mawr College “Monumental Melodrama: Mikhail Kalatozov’s Retrospective Return to 1920s Agitprop Cinema in I Am Cuba ” October 2013 Few artists have bridged the large thirty-year divide between the early Soviet avant-garde period of the 1920s and the post-Stalinist Thaw of the late 1950s and early 1960s like the filmmaker Mikhail Kalatozov. Thriving in these two periods of relative artistic freedom and innovation for Soviet culture, the Georgian-born Kalatozov—originally Kalatozishvili— creatively merged the ideological with the kinesthetic, first through his constructivist-inspired silent work and then through his celebrated Thaw-era films. Having participated in the bold experiment that was early Soviet cinema, Kalatozov subsequently maintained some semblance of cinematic productivity under Stalinism; but then in the late 1950s he suddenly transformed himself and his cinematic vision. -

FILM STUDIES COMPONENT 2 Silent Cinema Student Resource CASE STUDY: SUNRISE (MURNAU, 1927) Silent Cinema Student Resource Case Study: Sunrise (Murnau, 1927)

GCE A LEVEL WJEC Eduqas GCE A LEVEL in FILM STUDIES COMPONENT 2 Silent Cinema Student Resource CASE STUDY: SUNRISE (MURNAU, 1927) Silent Cinema Student Resource Case Study: Sunrise (Murnau, 1927) Sunrise exemplifies filmmaking at its artistic peak during the late silent period. Director F.W. Murnau used every device available to filmmakers at the time to produce a lyrical, artistic and timeless love story. Sight and Sound magazine voted Sunrise the fifth greatest film ever made in their 2017 Greatest Films poll. The film is hailed by critics as a masterpiece. Martin Scorsese described the film as a “super-production, an experimental film and a visionary poem”. Sunrise was directed by German director F.W. Murnau as a ‘prestige picture’ for Fox studios. Although Sunrise is a silent film, it was produced with a synchronised score and released just weeks before the first ‘talkie’,The Jazz Singer. In this regard, it is a hybrid between a silent and sound film. Its unique context, as a German Expressionist film produced for a Hollywood studio and as a hybrid silent and sound film, ensures it is a fascinating film to study. Task 1: Contexts – before the screening It is likely that you will have little awareness of German cinema of the 1920s or the production contexts of Sunrise. This exercise will enable you to contextualise the film and guide your expectations before the screening. In small groups, you will be given an aspect of the film’s context to research. You will feed back to the group in the form of a short presentation or a handout. -

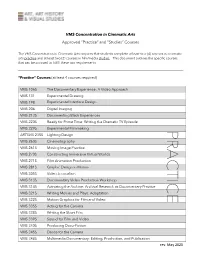

Practice” and “Studies” Courses

VMS Concentration in Cinematic Arts Approved “Practice” and “Studies” Courses The VMS Concentration in Cinematic Arts requires that students complete at least four (4) courses in cinematic arts practice and at least two (2) courses in film/media studies. This document outlines the specific courses that can be pursued to fulfill these two requirements. “Practice” Courses (at least 4 courses required) VMS 106S The Documentary Experience: A Video Approach VMS 131 Experimental Drawing VMS 198 Experimental Interface Design VMS 206 Digital Imaging VMS 213S Documenting Black Experiences VMS 220S Ready for Prime Time: Writing the Dramatic TV Episode VMS 229S Experimental Filmmaking PRACTICE ARTSVIS 235S Lighting Design VMS 260S Cinematography VMS 261S Moving Image Practice VMS 270S Constructing Immersive Virtual Worlds VMS 271S Film Animation Production VMS 281S Graphic Design in Motion VMS 305S Video Journalism VMS 313S Documentary Video Production Workshop VMS 314S Activating the Archive: Archival Research as Documentary Practice VMS 321S Writing Movies and Plays: Adaptation VMS 322S Motion Graphics for Film and Video VMS 335S Acting for the Camera VMS 338S Writing the Short Film VMS 339S Sound for Film and Video VMS 340S Producing Docu-Fiction VMS 345S Dance for the Camera VMS 348S Multimedia Documentary: Editing, Production, and Publication rev. May 2020 VMS 351 3D Modeling and Animation VMS 356S Editing for Film and Video VMS 357S Digital Storytelling and Interactive Narrative 359A Introduction to Global Los Angeles: An Interdisciplinary -

Hearing Corporeal Memories in Cameraperson and Stories We Tell

Towards Affective Listening: Hearing Corporeal Memories in Cameraperson and Stories We Tell THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alper Gobel, B.A. Graduate Program in Film Studies The Ohio State University 2019 Master’s Examination Committee: Margaret Flinn, Advisor Erica Levin Sean O’Sullivan Copyrighted by Alper Gobel 2019 Abstract This thesis focuses on two documentaries: Kirsten Johnson’s Cameraperson (2016) and Sarah Polley’s Stories We Tell (2012). By proposing the term affective listening, it foregrounds affective engagement with the voice of documentary. The thesis argues that listening to the materiality of voice(s) is inextricably bound up with embodied experiences of social subjects. Affective listening creates an auditory experience, establishing a direct link between worldly experiences of documentary subjects and corporeal memories. In both documentaries, listening to multiple voices requires attention to bodily expressions and sensations. The emphasis on corporeal expressions incorporates a multiplicity of affect conveyed through vocal conventions of documentary such as the voice-over and the interview. Consistent with the two documentaries, affective listening emphasizes a multiplicity of affect, a multiplicity that is ingrained corporeal memories. ii Dedication Dedicated to my mother, Sevim Sahin iii Vita 2013 (May).....................................................B.A. Radio, Television, and Film, Ankara University, -

Westminsterresearch Bombay Before Bollywood

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Bombay before Bollywood: the history and significance of fantasy and stunt film genres in Bombay cinema of the pre- Bollywood era Thomas, K. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Prof Katharine Thomas, 2016. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] BOMBAY BEFORE BOLLYWOOD: THE HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE OF FANTASY AND STUNT FILM GENRES IN BOMBAY CINEMA OF THE PRE-BOLLYWOOD ERA KATHARINE ROSEMARY CLIFTON THOMAS A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University Of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Published Work September 2016 Abstract This PhD by Published Work comprises nine essays and a 10,000-word commentary. Eight of these essays were published (or republished) as chapters within my monograph Bombay Before Bollywood: Film City Fantasies, which aimed to outline the contours of an alternative history of twentieth-century Bombay cinema. The ninth, which complements these, was published in an annual reader. This project eschews the conventional focus on India’s more respectable genres, the so-called ‘socials’ and ‘mythologicals’, and foregrounds instead the ‘magic and fighting films’ – the fantasy and stunt genres – of the B- and C-circuits in the decades before and immediately after India’s independence.